Cervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) is recognised as a premalignant glandular condition and is a precursor to invasive cervical adenocarcinoma.1 It usually affects women of childbearing age in which a more conservative approach is preferred.1–3 The incidence of both AIS and adenocarcinoma of the cervix has been increasing, especially among young women.4,5 Cervical conisation, or cone biopsy, can be performed using a scalpel (cold knife cone [CKC]), laser, or electrosurgery (loop electrosurgical excision procedure [LEEP]). For patients with squamous dysplasia (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN]) there appears to be no difference in outcomes between techniques.6,7 However, it remains unclear if CKC is preferred over LEEP in patients with AIS. Studies have consistently shown that patients with AIS with a positive margin after an excisional procedure of the cervix are at significantly higher risk for residual disease.2,8,9 In addition, several studies have shown that a higher proportion of patients with AIS have negative margins if they undergo CKC versus LEEP.8,10,11 However, it remains unclear if this is due to a larger specimen being obtained when CKC is performed compared with LEEP.

For women who desire future fertility, conservative management with cervical conisation is considered a feasible option.1 However, the treatment can be challenging in women with AIS where the lesions are often located high in the endocervical canal, and may be multifocal. Repeat conisations are often required until negative margins are obtained.2 In addition, an unnecessarily large specimen is sometimes removed in an attempt to be certain of obtaining negative margins. These large and repeat cervical conisations are known to be associated with adverse obstetrical outcomes, including preterm delivery and low birth weight infants.12–14 It remains unclear if CKC should be performed over LEEP in patients with AIS in order to obtain negative margins. Furthermore, to date, there are limited data comparing specimen size between LEEP and CKC, and the correlation between specimen size and positive margins is largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to compare cone specimen size obtained using LEEP compared with CKC in patients with AIS. In addition, we sought to determine if there was any association between cone size and positive margins.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, of all women diagnosed with cervical AIS between 1998 and 2013. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained with a waiver of informed consent. Patients were identified using computerised databases from the Departments of Gynecologic Oncology and Pathology and were included if they had a diagnosis of AIS on cervical biopsy, cone specimen and/or hysterectomy and had undergone a CKC or LEEP. Patients with invasive disease and those without documentation of cone specimen size and/or margin status were excluded. All pathology slides were read by a gynecologic pathologist with expertise in cervical cancer and pre-invasive disease. Medical records were reviewed for demographic data, treatment history, pathologic findings, including the dimensions of the cone specimens and margin status, as well as outcomes. A positive margin was defined as AIS within 1 mm of the surgical margin. The follow-up period was defined as the time between initial AIS diagnosis and the date of last contact.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Specimen size, including length (distance from the external cervical os to the endocervical margin) and volume were compared between LEEP and CKC and correlated with margin status. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare medians between procedure types. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare distributions of categorical variables between procedure type, excluding “unknown” categories. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at MD Anderson.15

Results

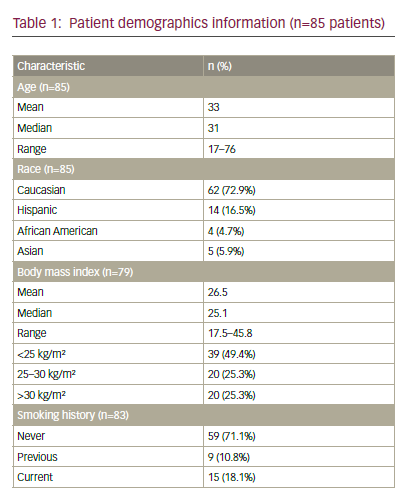

Between 1998 and 2013, 85 patients were diagnosed with cervical AIS and met inclusion criteria for the study. Patient demographic and pathologic information is summarised in Table 1. The mean age at diagnosis was 33 years (range 17–76 years). Of the 83 patients with smoking history

available, 29% were current or former smokers. A co-existing squamous lesion was present in 65 patients (76%).

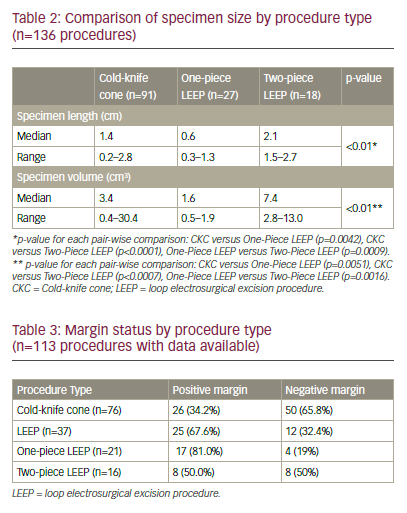

The 85 patients included in the study underwent a total of 136 procedures, including 91 CKCs (67%) and 45 LEEPs (33%). Of the 45 LEEP procedures, 27 were removed as a single specimen (one-piece LEEP) and 18 were removed as two specimens, an ectocervical specimen and a deeper endocervical top-hat specimen (two-piece LEEP). Specimen size and volume by procedure type are shown in Table 2. The median specimen length was significantly longer for the two-piece LEEP specimen (2.1 cm, range 1.5–2.7) compared with CKC (1.4 cm, range 0.2–2.8, p<0.01) and one-piece LEEP (0.6 cm, range 0.3–1.3, p<0.01). In addition, cone specimen median volume was significantly greater for two-piece LEEP (7.4 cm3, range 2.8–13.0) compared with CKC (3.4 cm3, range 0.4–30.4, p<0.01) and one-piece LEEP (1.6 cm3, range 0.5–1.9, p<0.01).

A higher rate of positive margins was noted when comparing all LEEP specimens (67.6%) with CKC specimens (34.2%), p<0.01 (Table 3). However, when the one-piece and two-piece LEEP specimens were analysed separately, the one-piece LEEP specimens had a significantly higher rate of positive margins (81.0%) compared with CKC p<0.01,

but there was no significant difference in the rate of positive margins between two-piece LEEP (50.0%) and CKC (34.2%) specimens, p=0.26. Also, there was no association between margin status and specimen length or volume.

In our cohort, many women underwent multiple procedures to achieve negative margins. Forty-one patients (48.2%) required more than one cone biopsy (CKC or LEEP) to obtain negative margins: 33 patients underwent two cone biopsies; six patients underwent three cone biopsies; and two patients underwent four cone biopsies. Furthermore, 35 of the 85 patients (41.2%) initially treated with LEEP or CKC ultimately underwent a simple hysterectomy. Final hysterectomy specimen showed residual AIS in six patients (17.1%). Four of these six patients (66.7%) had either positive margins or positive endocervical curettage (ECC) above the cone bed on the LEEP or CKC performed prior to the hysterectomy. The median follow-up for all patients was 48 months (range 0–163 months). None of the patients in our cohort were found to have invasive cancer during the follow-up period. However, one patient developed recurrent AIS at the vaginal cuff 2 years following hysterectomy for AIS requiring upper vaginectomy and was without evidence of disease with two years of follow-up. Post-treatment pregnancy outcome data was not available for the cohort.

Discussion

The primary finding from our study is that a two-piece LEEP with both ectocervical and endocervical specimens (top-hat) produces a larger specimen size with similar rates of positive margins compared with CKC. Given the decreased cost and morbidity of LEEP, a two-piece LEEP could be considered in the management of women with AIS desiring future fertility. We also noted that regardless of procedure performed, repeat conisations with LEEP and/or CKC are often required to obtain negative margins in patients with AIS.

The standard recommended treatment for AIS was previously hysterectomy for all patients due to the high-risk of underlying invasive carcinoma and presence of multi-focal or “skip” lesions. However, many reports have shown conservative management with cervical conisation to be safe and effective in women who desire future fertility provided negative margins are obtained.1–3,11 Salani et al. performed a meta-analysis of 33 studies, which included a total of 1,278 patients with AIS.2 They noted that a positive conisation margin was associated with a significant risk of residual disease (odds ratio [OR]=4.01) and of recurrent disease (OR=2.48). Furthermore, underlying invasive adenocarcinoma was more commonly associated with positive margins (5.2%) compared with negative margins (0.1%). A subsequent systematic review by Baalbergen and colleagues evaluated 35 studies of women with AIS who underwent conservative management with a cone biopsy (LEEP or CKC).16 They noted a recurrence rate of 5% after cone biopsy with positive margins and 3% with negative margins. In addition, they noted the risk of underlying malignancy to be less than 1%. The authors of both studies concluded that conservative treatment with cone biopsy with negative margins is an acceptable option for women with AIS who desire future fertility. Both reports also noted that multiple conizations may be required to obtain negative margins. Similarly, in the current study 41 patients (48.2%) underwent more than one cone to achieve negative margins.

Several studies have shown that a higher proportion of patients have negative margins if they undergo CKC compared with LEEP, particularly in cases of AIS.10,11,17 Our group previously performed a retrospective analysis of 188 patients with AIS.11 One hundred and seventy-two patients had at least one cone biopsy performed, with 110 (64.0%) undergoing a CKC, and 62 (36.0%) undergoing a LEEP as their initial method of treatment. Positive margins were noted in 35.0% of patients undergoing CKC compared with 55.6% undergoing LEEP (p=0.017). However, the study did not compare the size of the cone specimen between CKC and LEEP and it was unclear if this difference was due to a larger specimen being obtained when CKC was performed.

Previous reports in patients with squamous CIN have shown an association between cone specimen size and margin status.18–20 Milinovic et al. found that no patients with CIN had positive margins if a cone length of 15 mm (nulliparous patients) or 18 mm (multiparous patients) was obtained.18 A subsequent study by Kleimann and colleagues showed the likelihood of complete resection of CIN II/III was 100% with a cone height of 20.0 mm, 95% with a cone height of 13.0 mm and 90% with a cone height of 11.0 mm.19 Furthermore, Papoutsis et al. reported that a cone depth of <10 mm was a risk factor for predicting positive resection margins.20 However, no patients with AIS were included in these studies comparing specimen size with margin status.

A higher volume of resected tissue in a conisation may be associated with a higher risk for adverse obstetrical outcomes including preterm delivery. A meta analysis of 20 studies that included over 12,000 deliveries in patients with prior treatment for CIN showed that LEEP was not associated with a significantly higher risk of severe preterm delivery or perinatal mortality.13 However CKC was shown to be associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality and preterm delivery. A subsequent study that included over 18,000 deliveries in England found the risk of preterm delivery to be significantly lower than previous studies and concluded that treatment for CIN was a confounding factor and not the cause of preterm delivery.21 An additional study by Barreta et al. evaluated the association of the depth of surgical excision and preterm delivery in 47 patients after cervical conisation for CIN.22 The authors found a statistically significant inverse correlation between depth of surgical excision and gestational age at birth, with a cone depth of 1.5 cm having the greatest risk.22

In the current study, we found that the two-piece LEEP specimen had a median length that was significantly longer (2.1 cm) compared with CKC (1.4 cm) and a one-piece LEEP (0.6 cm). In addition, cone specimen median volume was significantly greater for two-piece LEEP (7.4 cm3) compared with CKC (3.4 cm3) and one-piece LEEP (1.6 cm3). Furthermore, when the one-piece and two-piece LEEP specimens were analysed separately, the one-piece LEEP specimens had a significantly higher rate of positive margins (81.0%) compared with CKC (34.2%), but there was no significant difference in the rate of positive margins between two-piece LEEP (50.0%) and CKC (34.2%). These results suggest that a larger LEEP (i.e., a two-piece LEEP or top-hat) may have the same outcomes as a CKC. Compared with CKC, LEEP can be performed in the outpatient setting, requires only local anaesthesia, and has a lower associated cost and morbidity. LEEP may therefore be a reasonable alternative to CKC for patients with AIS.

Our findings are similar to those of Munro et al. who compared the results of 338 patients diagnosed with AIS who underwent CKC (n=231) or LEEP (n=107).23 They noted no significant differences in the incidence of persistence and/or recurrence of AIS according to the type of excisional procedure. The authors concluded that CKC and LEEP are equally effective in the management of AIS in women wishing to preserve fertility. They also noted that patients with positive margins were 3.4 times more likely to have disease persistence or recurrence.

Our study is limited by retrospective data collection, a long study period, data from a single institution with possible referral bias, and a lack of post-treatment fertility and pregnancy outcomes. Furthermore, our power was limited by the small number of patients who underwent a two-piece LEEP. Despite these limitations, this study included a large number of patients overall and is one of the first studies to compare specimen size with margin status in patients with AIS. Our findings suggest that a two-piece LEEP with both ectocervical and endocervical specimens produces a larger specimen size with similar rates of positive margins compared with CKC. In addition, given the decreased cost and morbidity of LEEP, a two-piece LEEP should be considered in the management of women with AIS desiring future fertility. Furthermore, it is important to obtain negative cone margins in patients with AIS regardless of procedure performed.