Introduction

Presented by Sean Bohen

Oncology is one of the cornerstone therapeutic areas for AstraZeneca, and within the AstraZeneca oncology drug discovery platform there are four main research areas: tumour drivers and resistance, immuno-oncology, antibody conjugates and the DNA damage response (DDR). The pursuit of oncology drugs targeted at the DDR is based on tumour genetics. Tumours arise when there is an accumulation of genetic defects that compromise the ability to respond to normal growth controls and/or drive the tumour to grow. By 2010, sequencing of more than 100,000 cancer genomes (including many types of cancer) had identified 130,000 different mutations in over 3,000 separate genes.1 Within these genes two major types of driver genes were found: oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes. Approximately 10% of driver genes were classified as oncogenes (genes which if they gain function and start working in a non-regulated way promote tumour growth). Oncogenes are good potential drug targets as therapies can be designed to shut down unregulated gene or protein expression. Tumour suppressor genes are the more common type of driver genes, comprising approximately 90% of mutations, and serve as checkpoints in the prevention of unregulated cell growth. Loss of function mutations in tumour suppressor genes are much harder to target therapeutically. All of the approximately 330 identified driver genes can be assigned to one of 12 core cancer pathways that regulate three core cellular processes: cell fate, cell survival and genome maintenance.1 DNA damage response is a pathway involved in all of these core cellular processes and here we discuss the importance of DDR in cancer cells, the development of DDR inhibitors, potential strategies for increasing the efficacy of DDR targeted therapies and the identification of new DDR targets and drugs.

Targeting DNA damage response in cancer – past, present and future

Presented by Mark J O’Connor

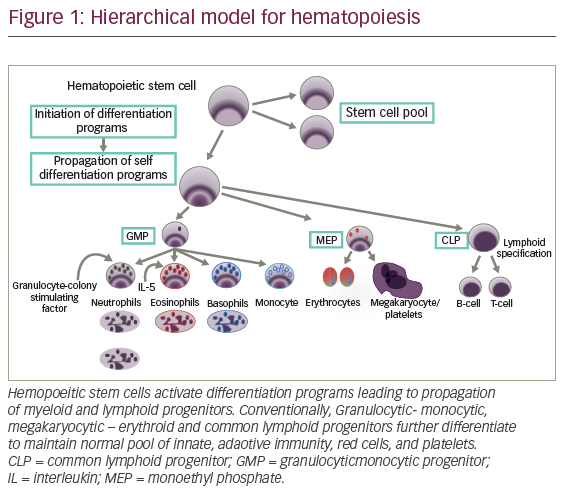

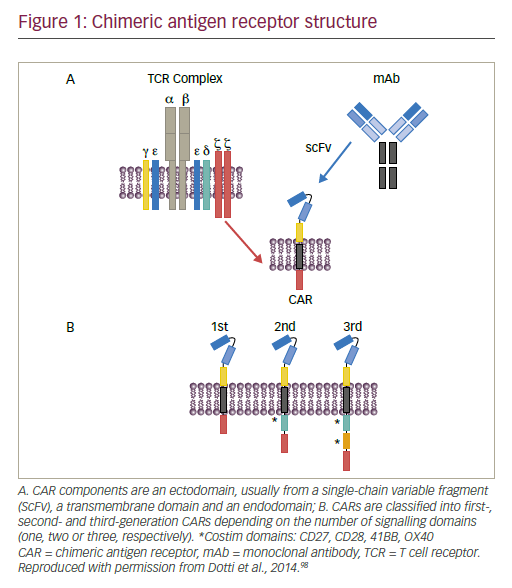

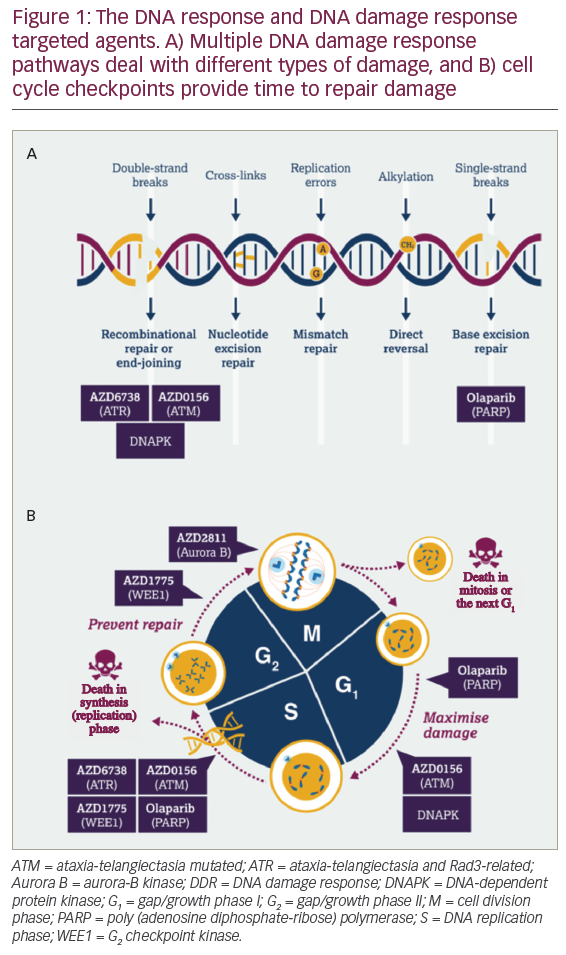

DNA damage response is a broad term for the many different cellular responses to DNA damage. DNA damage response is an essential group of processes as tens of thousands of DNA damage events occur in every cell in the body every day.2 DNA damage response does not just comprise DNA repair mechanisms but also includes cell cycle checkpoints to halt replication while DNA damage is being repaired, intra- and inter-cellular signalling events affecting epigenetics and gene expression and control of decisions on cell senescence or cell death. There are also links between DDR and modulation of the immune response.3 Two factors determine the type of DDR initiated by the cell following DNA damage: the type of DNA damage (Figure 1A) and when in the cell cycle the damage occurs (Figure 1B). Multiple DDR pathways have evolved to deal with different types of DNA damage.3 For example, following DNA double-strand breakage, if the DNA has been previously replicated and there is undamaged DNA template the cell will preferentially use the high fidelity homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway. However, if the HRR pathway is not available or the DNA has not been replicated, cells must rely on an error prone end-joining pathway. When targeting the DDR, DNA repair pathways, DNA damage signalling and cell cycle checkpoints are all potentially interesting drug targets.

Given how important DDR is to the cell, why is DDR a good potential anticancer target? Cancer cells have three key differences when compared to normal cells: they have a greater level of endogenous DNA damage; they have higher levels of replication stress; and they often have the loss of one or more DDR pathway.3 These cancer-specific DDR deficiencies can potentially be exploited through synthetic lethality.3,4 Synthetic lethality is the concept that if one or more pathway is missing, this leads to an absolute dependence on the remaining pathway (Figure 2). In a normal cell, two DDR pathways are present that can resolve DNA damage and therefore if one pathway is inhibited, the second pathway can take over. However, when targeting a cancer that has already lost pathway A, inhibiting pathway B has the potential to drive cancer-specific cell death (Figure 2).

How did DNA damage response become an important strategy for treating cancer?

KuDOS Pharmaceuticals, formed in 1999, was the first company to focus on targeting DDR based on research from Professor Steve Jackson’s laboratory.5 Olaparib is an oral poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor discovered at KuDOS Pharmaceuticals in 2004 and acquired by AstraZeneca in 2006. It is the first DDR inhibitor to have been granted regulatory approval.3 The PARP protein identifies and binds to single-strand breaks, utilising nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to form poly ADP-ribose chains, which modifies and opens up chromatin, allowing DNA repair proteins access to the DNA.6 Automodification of the PARP protein by formation of the poly ADP-ribose chains leads to the dissociation of the PARP protein, which then allows the repair proteins to bind and repair the single-strand break. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors prevent the formation of the poly ADP-ribose chains and trap PARP on the DNA at the single-strand break.7,8 These trapped PARP-DNA complexes can lead to the stalling and/or collapsing of replication forks, resulting in the generation of double-strand breaks.6 In a normal cell, the HRR pathway can repair this break effectively and accurately, but in cancer cells that have lost this pathway (for example those that have a mutated breast cancer 1 [BRCA1] protein), cells must use the error prone end joining repair pathway and after a few rounds of trying to replicate in the presence of PARP inhibitors, this leads to an accumulation of genomic instability and cancer cell death. To summarise, PARP inhibition leads to DNA double-strand breaks and a dependency on the HRR pathway.

Data published in 2005 demonstrated the potential for PARP inhibitors to induce cell death in BRCA-deficient cells through the concept of synthetic lethality.9,10 In this preclinical study, BRCA homozygous mutant cells were approximately 1,000-fold more sensitive to the PARP inhibitor olaparib when compared to BRCA heterozygous and wild-type cells.9 This is important because in a patient with germline BRCA mutations, every cell in the body will have one functional copy of the BRCA gene but only tumour cells will have lost the second functional copy and will be more sensitive to PARP inhibition.

Clinical validation of synthetic lethality and DNA damage response therapies

The first clinical validation of the concept of synthetic lethality was seen in the initial phase I study of olaparib. The study enrolled a total of 60 patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced solid tumours that were refractory to standard therapies.11 While it was not initially required for eligibility that patients be carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, in the expansion phase of the study, only carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were enrolled. A total of nine patients were found to have partial or complete radiologic response following olaparib treatment. Impressive early results were seen in the peritoneal mass of patient 20, which shrank from 53 mm to 18 mm post-treatment.

In addition to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins, there are many other proteins involved in the HRR pathway and this suggested an opportunity to use PARP inhibitors beyond patients with BRCA mutations.12 In 2011, a phase II study (NCT00679783) of olaparib in 91 patients with recurrent high-grade serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer, demonstrated activity of PARP inhibitors in shrinking tumours outside of the germline BRCA population.13 Confirmed objective responses were seen in seven (41%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 22–64) of 17 patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and 11 (24%, 95% CI 14–38) of 46 without mutations. Following up from these results, Study 19 (NCT00753545) was a placebo-controlled clinical trial of maintenance treatment with olaparib in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, high-grade serous ovarian cancer who had received two or more platinum based regimens.14 In this study, the mixed patient population progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly longer with olaparib than with placebo (median, 8.4 months versus 4.8 months; hazard ratio (HR) for progression or death, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.25–0.49; p<0.001).14 However, in patients with a BRCA mutation, the median PFS was 11.2 months versus 4.3 months in the placebo group (HR 0.18; 95% CI, 0.10–0.31; p<0.0001).15 The results from this study led to approval of olaparib in Europe in 2014 and was quickly followed by the approval of olaparib in the US in the same year.

In Study 19, eight 50 mg capsules of olaparib were taken twice daily, equivalent to a daily dose of 800 mg and a total of 16 capsules per day. To reduce capsule burden, a tablet formulation of olaparib was developed, requiring patients to ingest two 150 mg tablets, twice daily, equivalent to a dose of 600 mg and a total of four tablets per day. To confirm the findings from Study 19, a phase III trial was initiated of olaparib in patients with BRCA mutated ovarian cancer after complete or partial response to platinum chemotherapy (SOLO-2/ENGOT-Ov21) (NCT01874353) using the newer tablet formulation of olaparib.16 The SOLO-2/ENGOT-Ov21 study was an international, multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial that evaluated olaparib tablet maintenance treatment in platinum-sensitive patients with relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation who had received at least two lines of previous chemotherapy (n=295). Investigator-assessed median PFS was significantly longer with olaparib (19.1 months; 95% CI, 16.3–25.7) than with placebo (5.5 months; 95% CI, 5.2–5.8; HR 0.30; 95% CI 0.22–0.41; p<0·0001). In August 2017, olaparib was granted US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for maintenance treatment of adult patients with recurrent, epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer who are in a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status.

In addition to olaparib, two other PARP inhibitors, rucaparib and niraparib, have shown similar activity in patients with BRCA and in patients with high-grade serious ovarian cancer.17,18 Niraparib was granted approval by the FDA on 27 March 2017 for use in both patients with BRCA mutant and BRCA wildtype. Rucaparib has FDA approval for use in BRCA mutant populations, however a supplemental new drug application was submitted to the FDA for use in patients with BRCA wildtype in October 2017.

The average survival time for patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer is usually around 2–3 years. In Study 19, clinically significant long-term maintenance treatment with olaparib has been observed.19 One in five patients were still on olaparib treatment at 3 years, one in seven patients were still on treatment at 5 years and a durable treatment benefit was seen in ≥10% of patients with BRCA mutant and BRCA wildtypes, who continued to receive and benefit from olaparib for ≥6 years.

Strategies for increasing the efficacy of DNA damage response targeted therapies

What other evidence do we have that targeting DDR has the potential to increase efficacy and the number of potential cures? In 2014, a study described an outlier response in a patient with metastatic small cell cancer of the ureter, in which the patient achieved a complete response that was durable despite drug therapy discontinuation for nearly 3 years.20 In this study, the patient was treated with irinotecan (a chemotherapy agent that causes DNA double-strand breaks) in combination with AZD7762 (an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-competitive checkpoint kinase [Chk1/2] inhibitor). The patient’s tumour was characterised and found to have a RAD50 mutation (a gene involved in DNA double-strand break repair) and a mutation in p53. Due to the RAD50 mutation, tumour cells were unable to repair DNA double-strand breaks induced by irinotecan. Concurrent treatment with the Chk1/2 inhibitor meant that there was an override of the cell cycle checkpoint reducing the opportunity to repair the DNA. The combination of DNA damage and tumour specific DDR deficiencies at multiple points in the cell cycle led were attributed to such an impressive patient response. This is an exemplification of the treatment concept that AstraZeneca is trying to reproduce using DDR inhibitor combinations that are synthetically lethal in tumour cells but not in normal cells with somatic mutations. Thus, the AstraZeneca DDR inhibitor pipeline targets include the key single-strand break and double-strand break pathways as well as the ability of the cell to undergo repair throughout the cell cycle (Figure 1).

Lastly, the use of DDR inhibitor combinations is not the only approach that could potentially increase therapeutic efficacy, as there is new data emerging regarding links between DDR and the immune response.21–23 DDR engages the immune response at multiple levels and these mechanisms include induction of the inflammatory response,24 the generation of immune cell diversity through V(D)J recombination,25 the generation of neo-antigens through impaired DNA mismatch repair (MMR),26 immune priming through the antiviral early warning system,23 and the requirement of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) regulation for immune-mediated cell killing.27 In a study by Le et al., MMR–deficient status and subsequent microsatellite instability predicted clinical benefit of the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab.21 Microsatellite instability is a predisposition to mutation resulting from impaired DNA MMR but also impacts DNA double-strand break-repair capability due to microsatellite deletions in the ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM) gene. In addition, there are interesting links between DDR and ancient antiviral immune response, as retention of DNA in the cytoplasm of the cell can lead to activation of type I interferon genes and the STING-dependent innate immune signalling pathway.23 DNA damage response–deficient breast cancer cells have been demonstrated to have increased cytosolic DNA and constitutive activation of the viral response cGAS/STING/TBK1/IRF3 pathway.

In summary, DDR inhibition has the potential to revolutionise the way we treat people with cancer. DNA damage response deficiencies are common across multiple cancers, and targeting them has been clinically validated with a subset of patients experiencing long-term benefit following DDR inhibitor treatment. To increase therapeutic efficacy, there is potential for DDR inhibitors to be combined with each other as well as other targeted agents to deliver step changes in clinical response. Finally, there is significant scientific rationale and clinical evidence that DDR and immune responses are linked and potentially synergistic. As we better understand the interactions between DNA damage, DDR and the immune response there is potential for increasing clinical efficacy by combining DDR inhibitors with immune-directed therapies.

The potential of DNA damage response inhibitors in combination with radiation treatment

Presented by Meredith Morgan

Radiation is one of the most common treatments for cancer and is responsible for approximately 40% of cancer cures, second only to surgery.28 In the context of locally advanced cancer, radiation is the foundation of treatment. It is usually given concurrently with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy, the specific chemotherapy dependent on the disease site. However the efficacy of these regimens differs across disease sites, with high 5-year survival rates in rectal cancer (~60%),29 and much lower 5-year survival rates in glioblastoma30 and pancreatic cancer (~10%).31

In the last 20 years there have been major technological advancements in our ability to deliver radiation specifically to tumours.28 Modern intensity-modulated radiation treatment plans allow delivery of a very high dose of radiation specifically to a tumour while sparing radiation dose to the important surrounding tissues and have allowed escalation of radiation to the maximum level. Radiation is given in combination with full systemic doses of chemotherapy, so increasing chemotherapy or radiation doses is not the solution for improving therapy. There is a need for tumour cell selective therapies that can be integrated into treatment regimens to improve therapies without increasing toxicity.

DDR is a promising target for improving chemoradiation because DNA is the principal target of radiation.32 Radiation-induced cell death is caused by unrepaired DNA double-strand breaks.32,33 In response to radiation-induced DNA damage, cells activate the DDR. DNA damage response is a broad term encompassing a collection of processes in which cells pause in the cell cycle to allow for DNA repair, cells stop DNA replication to prevent replication of a damaged DNA template and cells activate DNA repair pathways.2 The DDR can promote resistance and survival of tumour cells in response to radiation therapy, and because of this, the core set of proteins that mediate the DDR have become very important cancer targets in the last 5–10 years.5 The DDR inhibitors prevent protective cellular responses to DNA damage, causing tumour cells to accumulate DNA damage and DNA replication stress that ultimately causes them to die in response to radiation therapy.34 Research has demonstrated that DDR inhibition increases radiosensitivity35,36 and therefore has the potential to improve survival in patients with locally advanced cancer.34,37

A common concern regarding the use of DDR inhibitors as therapeutics, is their potential effect on normal cells. During tumourigenesis there is an acquisition of mutations, many of which cause tumour cells to become defective in one or more of the DDR pathways.38 This causes cancer cells to have higher levels of endogenous DNA damage and replication stress when compared with normal cells and is a defect that can be exploited.3 DNA damage response inhibitors are synthetically lethal when combined with these tumour cell defects. This concept has been clinically validated with PARP inhibitors in BRCA mutant cancer11,15 and outside of the germline BRCA population,13 and new data is beginning to emerge about other important genetic characteristics that confer sensitivity to DDR inhibitors.39,40 Radiation can potentiate this process because it induces DNA damage specifically in tumour cells and may broaden the therapeutic efficacy of DDR inhibitors to tumour cells without defined mutations.37

Strategy 1 – DNA damage response inhibition with standard-of-care

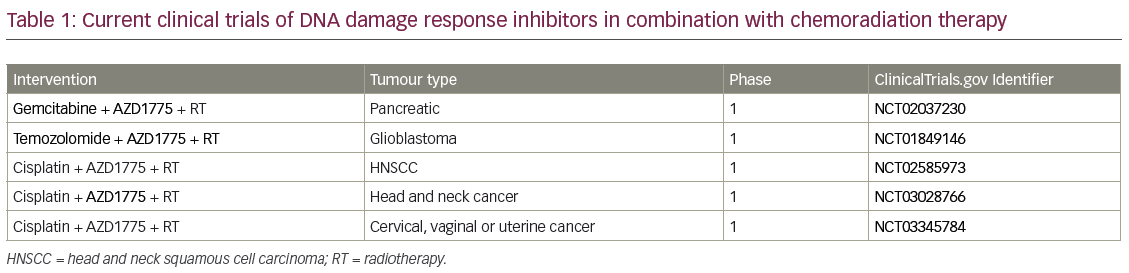

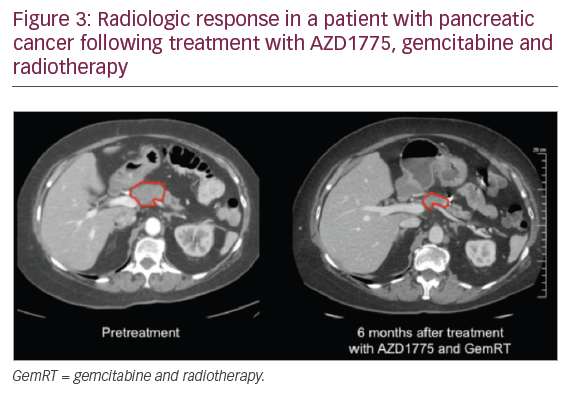

When combining standard-of-care chemoradiation therapy with DDR inhibitors, DDR inhibitors can be used to sensitise tumour cells to both chemotherapy and radiation. For a patient this potentially translates into both improved local control and improved chemotherapy efficacy/systemic control. In addition, when DDR inhibitors are given as sensitisers, lower doses of chemotherapy agents can be used than for monotherapy, therefore potentially reducing toxicity. There are currently five on-going clinical trials combining a DDR inhibitor with chemoradiation (Table 1). A phase I trial investigated the G2 checkpoint kinase (WEE1) inhibitor AZD1775, in combination with gemcitabine and radiation therapy (Gem-RT), in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Although this trial is still ongoing, to date the median overall survival data are promising and compare very favourably to historical control data. In Figure 3, we show radiologic results from a patient in the trial with a large pancreatic mass. Six months after therapy the tumour was considerably reduced in size, the patient underwent a successful surgical resection and is currently alive with no evidence of disease 2.5 years after diagnosis. Given that the median overall survival is historically so short for locally advanced pancreatic cancer, this is a significant improvement.

Strategy 2 – DNA damage response inhibitor combinations

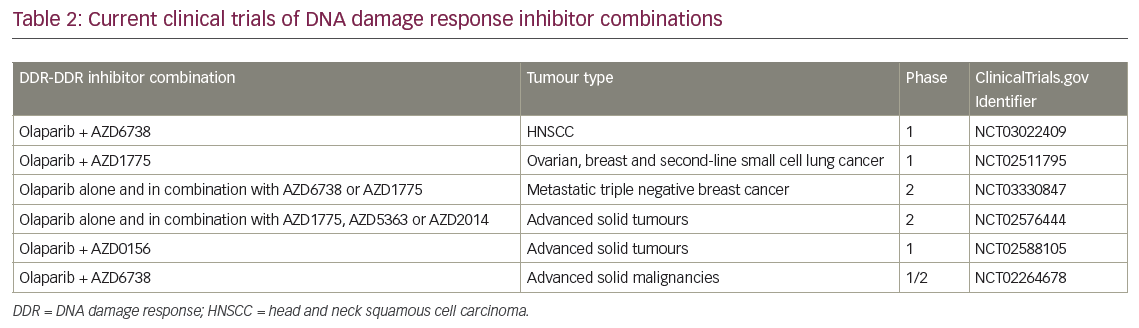

Combining DDR inhibitors is based on the idea that strategic combinations of DDR inhibitors might inhibit multiple pathways that cancer cells rely on for survival and result in greater therapeutic benefit. In BRCA mutant cancer, some combinations have been shown to induce profound radiosensitisation (e.g. WEE1-PARP),41 however only some combinations are therapeutic without radiation (e.g. Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated and Rad3-related protein kinase [ATR]-PARP).42 The ultimate goal for this strategy is to be able to replace cytotoxic chemotherapy and chemoradiation regimens with combinations of DDR inhibitors. In a preclinical study of mice with human pancreatic tumours treated with a WEE1 and PARP inhibitor combination, 20% of tumours did not grow back following therapy.41 These data underscore the potential of this therapy combination to be effective. Clinical trials are currently underway with several DDR-DDR inhibitor combinations in the absence of radiation (Table 2). However, it should be noted that integration of radiation has the potential to increase the therapeutic benefit of these combinations.

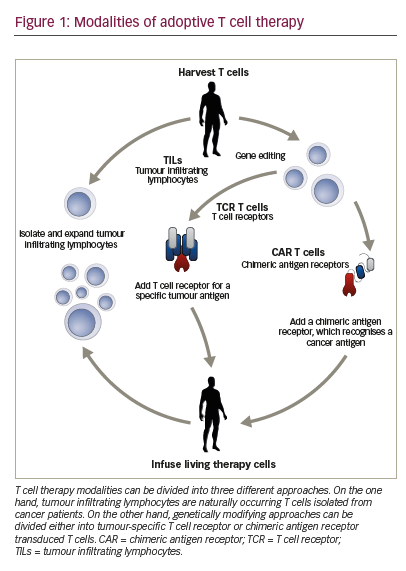

Strategy 3 – DNA damage response inhibitors as sensitisers to immunotherapy

There is potential for enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy by using DDR inhibitors and/or radiation as sensitisers. As previously outlined, radiation induces DNA damage in tumours cells. During this process damaged DNA is released from the nucleus in the form of chromosome fragments or small pieces of single- or double-stranded DNA which activates the innate immune response.43,44 The DDR inhibitors have the potential to enhance this process, making tumour cells more immunogenic and therefore more sensitive to immunotherapy. It has been demonstrated in the preclinical setting that radiation can enhance immunotherapy efficacy,45 and there are also preclinical data to suggest that in the absence of radiation some DDR inhibitors (e.g. PARP inhibitors) can synergise with immunotherapy.46 In contrast, not all DDR inhibitors work well with immunotherapy and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNAPK) inhibitors may be antagonistic.43 There are several clinical trials currently underway combining DDR inhibitors and programmed death-ligand 1 antibodies, and future integration of radiation has the potential to increase the therapeutic benefit of these combinations.

Strategy 4 – Basic discovery – a byproduct of DNA damage response therapeutics

One of the byproducts of the development of DDR inhibitors has been a very powerful set of tools available to scientists that have facilitated basic scientific discovery in the fields of DNA repair, DNA replication, the cell cycle and radiation biology.5 The discovery of these compounds has helped increase understanding of how DNA repair proteins are recruited to the DNA and to identify DNA repair pathways that were previously unknown. In turn, these advancements in basic science have the potential to identify new therapeutic targets.

Looking to the future

As treatment of metastatic cancer improves, therapy for locally advanced cancers will become increasingly important. Since standard radiation regimens are already escalated to maximum tolerable doses, integration of DDR inhibitors should permit further therapeutic gains. Future work will involve identifying additional cancer cell susceptibilities to DDR, better understanding the interactions between DDR-DDR inhibitor and DDR-immunotherapy combinations, and the potential use of radiation to broaden and deepen the therapeutic efficacy of these regimens.

DNA damage response inhibitor development – what’s next?

Presented by Sean Bohen

When examining the timeline of PARP inhibitor development, it took five decades from the discovery of PARP to the initiation of clinical studies that led to regulatory approval of PARP inhibitors. This is not an example of quick turnaround from target identification to drug, but it is hoped that the demonstration of the clinical utility of PARP inhibitors will accelerate subsequent research on DDR. AstraZeneca is currently building a portfolio of DDR agents that work across the DDR and include compounds that maximise DNA damage (PARP inhibitor; ATM inhibitor; ATR inhibitor) and those that prevent repair (WEE1 inhibitor and aurora B Kinase inhibitor) (Figure 1). While only three PARP inhibitors are currently approved for clinical use, there are an increasing number of DDR inhibitors that are being investigated both preclinically and in clinical trials.3 In addition to the identification of new DDR targets and drugs, treatment strategies for DDR inhibitors are also expanding due to the potential for therapeutic combination with other DDR inhibitors, with immunotherapies, and with targeted therapies (i.e. vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors). Due to increasing tumour characterisation and understanding of DDR pathways, there is the potential for the expansion of patient populations (i.e. from BRCA mutations, to HRR mutations, to other DDR mutations and tumour types). The current clinical approval of PARP inhibitors for the treatment of cancer is likely to be only the beginning of what could be a significant role for DDR-based agents in future cancer therapy.