Pathophysiology of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria

Pathophysiology of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria

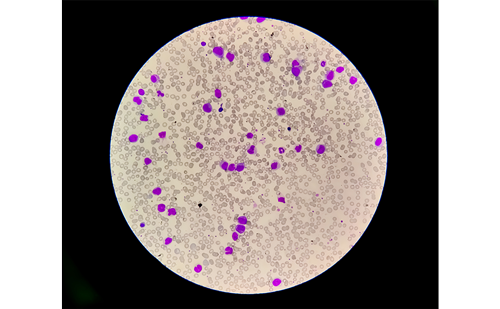

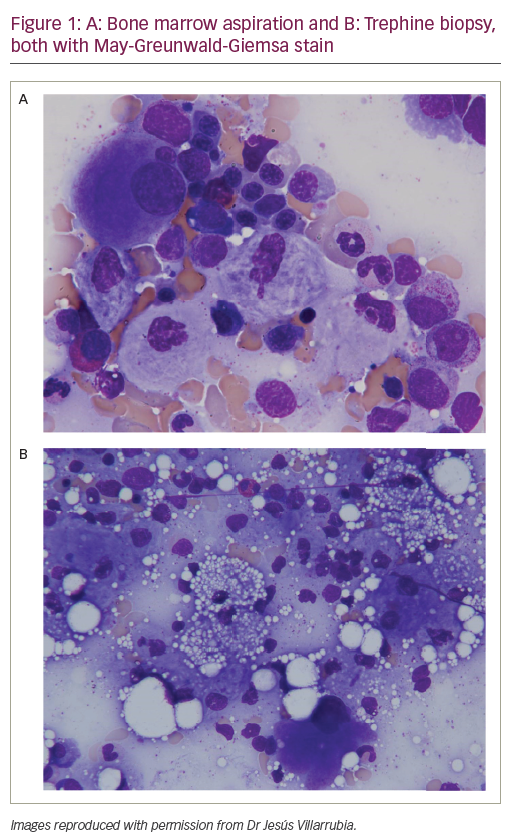

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) is a non-malignant clonal disorder of haematopoiesis.1 The genetic basis is acquired somatic mutations of the X-chromosomal gene PIG-A in one or few haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.2 The protein encoded by PIG-A is essential for the synthesis of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. The GPI moiety serves as the membrane anchor for a group of proteins, known as GPI-anchored proteins. These proteins are functionally diverse, and include CD14, CD16, CD24, CD28, CD48, CD52, CD55, CD58, CD59, CD66c, CD66b, CD73, CD87, CD90, CD108, CD109, CD157, CD317, GP500, GP175 and JMH-bearing protein.3–5 The expression of these proteins is either substantially reduced (PNH type II cells) or completely missing (PNH type III cells) on the cells arising from the PIG-A mutated stem or progenitor cell (see Figure 1). As PIG-A gene mutations in PNH are acquired somatic mutations, not all haematopoietic cells are affected. There is always a mosaic of PIG-A-mutated, GPI-deficient cells and non-PIG-A-mutated cells with normal expression of GPI-anchored proteins (see Figure 1).2 Interestingly, clonal populations of haematopoietic cells with PIG-A gene mutation and GPI-anchor deficiency are also present in normal individuals.6,7 Selection of GPI-anchor-deficient cells or secondary genetic events in PIG-A-mutated cells might be necessary for the expansion of the PNH clone(s).8

Measurement of expression of the GPI-anchored proteins by flow cytometry has become the gold standard for laboratory diagnosis of PNH and has replaced the Ham test and the sucrose lysis test (sugar water test).5,9 Flow cytometry allows sensitive and specific detection of even small GPI-deficient populations and a quantitative assessment of the size of the PNH cell population in various cell lineages, and can be used for both initial diagnosis and monitoring during follow-up.3,4,10–12

Clinically, PNH is characterised by the triad of acquired Coombs-negative intracorpuscular haemolytic anaemia, thrombophilia and bone marrow failure.1,9,13 The clinical presentation and the course of the disease are highly variable. Many of the clinical features of PNH can be attributed to the deficiency of the GPI-anchored proteins: two GPI-anchored proteins (CD55, CD59) are important for regulation of complement. Absence of these proteins from the surface of PNH red blood cells (RBCs) renders them susceptible to terminal complement-mediated lysis. CD59 blocks the terminal complement complex (membrane attack complex). Due to the absence of CD55 and CD59, PNH RBCs are highly sensitive to complement-mediated haemolysis. Severe haemolysis occurs predominantly in situations where complement activation is enhanced, thus in most instances these haemolytic crises occur in the context of infections, surgery, trauma or pregnancy. Chronic haemolysis with haemosiderinuria leads to iron deficiency in many patients.14,15

Thrombophilia is the leading cause of mortality in PNH. Thrombosis in PNH will occur in about 50% of patients with haemolytic PNH.9,13,16,17 Thrombosis can occur anywhere; however, it often occurs at ‘unusual’ sites such as hepatic, portal, splenic and mesenteric, cerebral and dermal veins.9,16 The risk of thromboembolic events seems to be directly related to the size of the PNH cell population (as measured by GPI-deficient granulocytes).12,16,18 In the study of Moyo et al., the odds ratio for risk of thrombosis was estimated to be 1.64 according to logistic regression modelling for a 10% change in PNH clone size.12 No patient with <61% PNH granulocytes developed a thrombosis, whereas 12 of 22 patients (54.5%) with ≥61% PNH granulocytes manifested with thrombosis.12 In the study by Hall et al., the 10-year risk of thrombosis was 5.8% in patients with <50% GPI-deficient granulocytes versus 44% in patients with >50% GPI-deficient granulocytes.16 The cause of thrombophilia in PNH is multifactorial (see Table 1).19 The scavenging of nitric oxide (NO) by free haemoglobin is a crucial event,20 contributing to both thrombosis and other PNH-related symptoms. Haemoglobin released from RBCs during haemolysis binds to haptoglobin, which is rapidly cleared from the circulation via binding to CD163.21 When the capacity of this haemoglobin-scavenging protein is saturated, free haemoglobin appears in the circulation and reacts with NO to produce nitrate (NO3) and methemoglobin.22 In addition, haemolysis releases arginase from RBCs.23 This enzyme converts L-arginine, the substrate for NO synthesis, to ornithine. A profound degree of NO consumption has been demonstrated in PNH patients.24 NO is a major regulator of smooth-muscle tonus, influences platelet function and interacts with components of the coagulation cascade.25 Decreased NO signalling via cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) leads to increased smooth-muscle tonus, which can result in typical symptoms of PNH, e.g. abdominal pain, dysphagia, erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. NO depletion also increases platelet aggregation, inhibits disaggregation of aggregated platelets and induces platelet adhesion, which together with local vasoconstriction contribute to thrombophilia (see Figure 2). Recent studies have demonstrated that there is a high incidence of progression to chronic renal insufficiency in patients with PNH. Renal damage in PNH has been associated with chronic haemolysis and subsequent haemosiderosis and/or microvascular thrombosis.25

Progressive pancytopenia occurs in a proportion of PNH patients. In a recent study of a large cohort of patients in France, the cumulative 10-year incidence of bicytopenia or pancytopenia was 19.2%.9 In contrast, a substantial proportion of patients (30–50%) who were initially diagnosed with otherwise typical aplastic anaemia (AA) have small proportions of GPI-deficient cells.26–28 In a long-term follow-up of a cohort of AA patients, the cumulative incidence of clinical PNH was 13%.29 Furthermore, multiple mutations of the PIG-A gene have been demonstrated in patients with otherwise typical AA.30

In order to reflect the variations in presenting features, clinical manifestations, and links to other disorders, the International PNH Interest Group (IPIG) proposed to classify the disease as classic PNH, PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder or subclinical PNH.1

Management of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria – General Aspects

Until recently, only two general treatment approaches were available: either stem cell transplantation, which had potential to cure but high treatment-related morbidity/mortality, or symptomatic treatment and prophylaxis of complications, which led to unsatisfactory long-term control of the disease.1,31 Thus, there was a need for new treatments to be developed. As the clinical symptoms of PNH are due to increased complement sensitivity of blood cells, inhibition of complement was a logical approach. Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits complement protein C5, is the first and so far only specific complement inhibitor approved for clinical use in PNH. Stem cell transplantation and eculizumab treatment will be discussed in more detail below.

Therapeutic options for PNH are listed in Table 2. Patients with ongoing haemolysis and erythroid hyperplasia should receive folic acid supplementation. Iron stores need careful monitoring. Iron repletion, preferentially by oral administration, should be performed.

RBC transfusion should be performed as required based on symptoms of anaemia. The transfused RBCs are resistant against complement-mediated lysis. They may even transfer CD55 and CD59 via microvesicles to the recipient GPI-deficient red cells.32 Iron overload is unlikely in classic haemolytic PNH, but could occur in AA-PNH syndrome. Transfusion requirements can greatly vary from patient to patient in the course of the disease (e.g. depending on the frequency and severity of haemolytic crises due to infections). Leukocyte-reduced RBCs with fewer than 1×106 residual leukocytes per unit should be used. Washing of RBCs is not recommended.33 It is controversial whether blood products for PNH patients should be irradiated.

A substantial subgroup of PNH patients has concurrent AA or will develop AA. Therefore, it must be determined how much of the anaemia is due to haemolysis and how much is due to bone marrow failure. Immunosuppressive treatment as established for AA (antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine A) can improve the impaired haematopoiesis that occurs in hypoproliferative PNH, but the haemolytic component of the disease is not altered by immunosuppressive therapy.34,35 The effect of immunosuppression on the size of the PNH clone is equivocal. Both expansion and decrease, and even disappearance, of PNH cells during immunosuppression have been observed.11,35,36

Androgens have been successfully used to treat anaemia in PNH.9,14 Corticosteroids can be used to attenuate haemolytic exacerbations; however, only some patients respond to steroids.14,37–39 Given the inconsistent response and their toxicity profile, it is debatable whether corticosteroids and androgens should be used for long-term treatment.1 Careful evaluation in terms of convincing evidence for beneficial effects in the individual patient is necessary, and monitoring is essential.

Levels of erythropoietin and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) are markedly elevated in PNH.40,41 Therefore, it has been questioned whether there is an indication for growth factors in PNH treatment at all;40 however, in some patients improvement of anaemia could be achieved by treatment with erythropoietin.38,42–45 In anecdotal cases, the course of GPI-AP-deficient cells suggests that the efficacy of erythropoietin can be due to either a preferential action on normal cells or the GPI-deficient erythroid clone.42,44 In particular, erythropoietin may be a suitable adjunct in patients who have reduced haemolysis during eculizumab treatment (see below), but who are still transfusion-dependent.46

In patients with hypoplastic PNH, a combination of G-CSF and cyclosporin can improve cytopenia and reduce the number of GPI-AP-deficient cells.47 In eculizumab-treated patients with reduced haemolysis who are still transfusion-dependent, promotion of erythropoiesis by addition of erythropoiesis-stimulating factors may further improve haemoglobin and render patients transfusion-independent, in particular in PNH with underlying bone marrow failure.46 Other approaches so far studied in animal models and not yet available for clinical treatment are the replacement of complement inhibitory proteins in PNH cells and gene therapy. Alternative artificial glycolipid anchors or single-chain antibody fragments (scFv) were used to anchor CD59 into the cell membrane (Prodaptin-CD59 and scFv-DAF), which restores resistance of PNH cells to complement in vitro.48,49

Curative Treatment – Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only treatment with curative potential.1 However, due to the high transplant-related morbidity and mortality, only a small group of PNH patients have been transplanted in the past.1,31 For example, only 268 allogeneic stem cell transplants were reported to the Registry of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) between 1978 and 2007.50

According to the recommendation of the IPIG criteria for consideration of transplantation are bone marrow failure (fulfilling criteria of severe aplastic anaemia) or major complications of PNH, i.e. recurrent life-threatening thromboembolic disease or refractory, transfusion-dependent haemolytic anaemia.1

Published single-centre experience using either conventional51–61 or reduced-intensity conditioning62–67 is summarised in Tables 3 and 4. Great heterogeneity of results exists, with the probability of overall survival ranging from <60 to 100%. Recent studies using reduced-intensity conditioning reported very favourable results. In retrospective analyses of registry data, overall survival after human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling transplant for PNH was 56% at two years (International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry [IBMTR])31 or 70% at five years (EBMT).50 The substantial differences in outcome most likely represent the heterogeneity in indication, timing of transplant, concurrent aplastic anaemia or complications (e.g. Budd-Chiari) present at the time of transplant. There is no evidence that results with matched unrelated donors are inferior to those with HLA-matched sibling transplants. For PNH-aplastic anaemia syndrome, a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and antithymocyte globulin (ATG) is recommended.1 For patients with classic PNH, the best regimen – in particular the role of reduced-intensity regimens – needs to be determined.

Unsatisfactory results are not due to relapse of PNH, which is a very rare event (see Tables 3 and 4). Transplant-related mortality is the major problem that needs to be addressed. In particular, future studies must address indications for stem cell transplantation, optimisation of conditioning regimens and donor selection.

Disease-modifying Treatment – Eculizumab

Eculizumab (Soliris®, Alexion Pharmaceuticals) is a humanised monoclonal immunoglobulin (IgG)-2/4K antibody directed against the terminal complement protein C5. Eculizumab contains the murine complementary-determining regions of m5G1.1 mAb, which were grafted onto the human framework light- and heavy-chain variable regions to minimise the potential for immunogenicity.68,69 Eculizumab binds to the complement protein C5 with high affinity and inhibits its cleavage to C5a and C5b, thereby preventing the generation of the terminal complement complex C5b–C9.68,69 Blockade of C5 completely blocks the terminal complement cascade with formation of the membrane attack complex irrespective of the pathway of complement activation. However, it does not interfere with the generation of components in the early steps of complement activation, which generate important mediators for immunoregulation and protection against infections.

Eculizumab has been evaluated in three trials in PNH patients.70–75 The first pilot study enrolled 11 patients with haemolytic PNH,71,75 and two phase III trials enrolled another 184 patients.70,72 The first phase III trial, TRIUMPH, was a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial that examined safety and efficacy in haemolytic PNH patients who had received at least four transfusions in the four months prior to enrolment and a platelet count >100×109/l.74 SHEPHERD was an open-label, non-placebo-controlled trial that examined eculizumab in a more heterogenous PNH patient population.70 Patients were required to have received at least one transfusion in the previous two years. A platelet count of ≥30×109/l was required. In both trials, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels of 1.5 times the upper limit of normal and a PNH type III RBC population of 10% or more were required.70,72

In all trials, a significant reduction of haemolysis as measured by LDH was observed across all treated participants. The reduction was observed after one week of treatment and was maintained throughout the whole treatment period. Control of chronic haemolysis in the PNH patients resulted in a decrease in transfusion requirements. In the TRIUMPH and SHEPHERD trials, 51% of patients achieved transfusion independence, and in both trials the transfusion requirements decreased significantly. In eculizumab-treated patients in whom transfusion independence was not achieved, transfusion requirements were reduced by 44% (data from TRIUMPH study).74 The reduction in intravascular haemolysis in the eculizumab group resulted in an increase in PNH type III erythrocytes, whereas the proportion of PNH type III granulocytes and monocytes did not change significantly.70,73,74 This means that a higher proportion of erythrocytes is vulnerable against complement-mediated lysis. In 16 patients from the clinical trial who discontinued eculizumab for various reasons, no serious rebound haemolysis was observed. However, patients should be closely monitored for at least eight weeks in cases of eculizumab discontinuation.

As eculizumab does not block the early stages of complement activation, C3 cleavage products are formed and bind to CD55/CD59-deficient RBCs. The inhibition of terminal membrane attack complex formation by eculizumab allows the survival of these cells, which otherwise would undergo a rapid intravascular haemolysis due to C5b–9 formation. A positive direct antiglobulin test due to C3d loading (and in some cases also C3c loading of PNH RBCs) seems to be a consistent finding during eculizumab treatment.92 This explains mild ongoing haemolysis via extravascular sequestration of RBCs loaded with C3 cleavage product.92 Normalisation of haemoglobin after splenectomy in a patient with eculizumab treatment and ongoing extravasal haemolysis has been reported.76

The immediate and sustained improvement in haemolysis had an impact on fatigue as measured by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue instrument: fatigue improved within one week of eculizumab treatment and this was maintained throughout the entire study period. The improvement of fatigue in the eculizumab-treated patients was observed regardless of baseline LDH levels.73 The eculizumab-treated patients also had significant improvements in terms of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire Quality of Life Questionnaires (EORTC QLQ-C30) on the scale for global health status, as well as in scales for functioning (role, social, cognitive, physical and emotional functioning scale) and in two symptom scales (fatigue, pain).70,74 These improvements occurred without complete resolution of anaemia. Furthermore, patients who did not achieve complete transfusion independence during eculizumab treatment experienced significant improvements in quality of life and fatigue.73 This provides further evidence that the diminished quality of life in PNH is also due to intravascular haemolysis and does not just reflect the severity of anaemia.

In general, eculizumab was safe and well tolerated.70,74 The most common adverse events reported in the eculizumab-treated patients were headache, nasopharyngitis, back pain and nausea. The headaches occurred within the first 24 hours after administration of the first two doses of eculizumab. Headache decreased after the first two doses of eculizumab. The headache after start of treatment may be related to a sudden increase of NO due to effective blockade of intravascular haemolysis and therefore cessation of NO scavenging by free haemoglobin. The decrease in headache after the first two doses may indicate a return of NO to physiological levels.70,74

Recently, a desquamating rash and hyperammonemia was reported in a patient following the first administration of eculizumab;77 the causality in this case is not clear and a drug–drug interaction with trimethprim–sulfamethoxazole was assumed.77 As the experience so far with eculizumab in this rare disease is limited, physicians must be vigilant for unexpected adverse events. It is known that individuals with inherited terminal complement deficiency have an increased risk of meningococcal infections. In eculizumab-treated patients, three cases of Neisseria meningitis infections have been reported.78 Across all PNH studies, infections did not seem to be more frequent in patients with eculizumab treatment compared with patients who received placebo.70,74

Eculizumab is administered in between 25 and 45 minutes as an intravenous infusion according to the following dosing schedule: an induction dose of 600mg every seven (±2) days for four weeks followed one week later by a 900mg dose and then 900mg every 14 (±2) days.70–73,75 A reduction in the dosing interval from 14 to 12 days was sufficient to maintain the levels of eculizumab necessary to completely block intravascular haemolysis in patients who experienced breakthrough haemolysis in the last days of the dosing interval.75 All patients due to receive eculizumab must receive N. meningitidis vaccine at least two weeks prior to commencement of eculizumab. Quadrivalent, conjugated meningococcal vaccines are strongly recommended. Patients must be informed about the early clinical signs of meningococcal infections and must be closely monitored.

Prevention and Treatment of Thrombosis

The most feared complications in PNH and the leading cause of disease-related death are thromboembolic events.9,13 Based on retrospective analysis, it was recommended to use primary prophylactic oral anticoagulation in patients with a large PNH cell population.16 In this study, no thromboembolic event occurred in patients who received primary warfarin prophylaxis, whereas the 10-year risk of thrombosis was 36.5% in patients without prophylaxis.

To study the impact of long-term eculizumab treatment on thromboembolism, the event rate in the clinical trials including the open-label extension trials was compared with the pre-treatment rate in the same patients.73 The event rate of venous or arterial thromboses prior to eculizumab was 7.37 events/100 patient-years. The most common sites were lower-extremity deep veins (18.5%), mesenteric/splenic veins (16.9%) and hepatic/portal veins (16.9%). With eculizumab treatment, the event rate dropped significantly to 1.07 events/100 patient-years (p<0.001).73 In the subgroup of patients who had received antithrombotic treatment, the thromboembolic event rate was 10.6 per 100 patient-years before eculizumab and was reduced to 0.62 events per 100 patient-years in the same patients during eculizumab treatment.73 Therefore, long-term administration of eculizumab reduces the risk of thrombosis in PNH.73

In acute thrombotic events, immediate anticoagulation with heparin should be started. Successful local or systemic thrombolytic therapy or radiological intervention has been reported in patients with acute onset of Budd-Chiari syndrome.79–82 After a thrombotic event, patients should be anticoagulated indefinitely.1

Currently, it is controversial how the results on eculizumab will change the recommendations for anticoagulant treatment in PNH. Further studies are needed to clarify whether eculizumab can replace primary or even secondary prophlyaxis. For decision-making on primary prophylaxis, all factors such as symptoms, size of PNH clone, other thrombophilic risk factors, treatment for PNH (in particular eculizumab) and other concomitant medication, platelet count, age, activity level, compliance and patient preference have to be taken into consideration.

Given the impact of thrombosis on mortality due to PNH,9,13 one could expect that eculizumab treatment, by decreasing the risk of thrombosis, might increase the life expectancy of these patients.

Conclusion

Recent developments have raised expectations for patients with PNH, and recent results on stem cell transplantation are encouraging. The approval of eculizumab made a targeted, disease-modifying treatment available that is well-tolerated and reduces haemolysis, transfusion requirements and risk of thrombosis and improves anaemia and quality of life.

The availability of eculizumab raises a lot of new questions. Does eculizumab change the indication for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, and if so how? Does eculizumab treatment prior to stem cell transplant influence outcome after stem cell transplantation. Does the drug treatment change the thrombosis prophylaxis? Could eculizumab treatment be combined with immunosuppression in patients with AA-PNH syndrome?

Eculizumab treatment is very expensive. Further follow-up of patients treated with eculizumab and analysis of outcome with eculizumab in comparison with other approaches are needed in order to study its long-term effects and in particular its impact on long-term survival. Well-designed clinical trials and follow-up of a large number of patients with this orphan disease by a worldwide patient registry is necessary to address these questions; in particular, the long-term follow-up of patients in an international registry can demonstrate how the recent changes in management will influence the natural history of PNH. ■