Treatment for prostate cancer impacts the health-related quality of life of men. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) data from prospective, investigator-initiated clinical trials have shown that effects are seen on the urinary, bowel, and sexual function domains and, to a lesser extent, on the general quality of life (QoL) of men.1–5 In these clinical studies, patients reported their sexual function to care specialists (e.g. physicians, research nurses, researchers) in a formal clinical setting, whereas peer-to-peer, anonymous reporting in a more informal setting may affect patients’ openness and hence their ability to comfortably share their true thoughts and experiences. Europa Uomo, the prostate cancer patient coalition in Europe, considered that the feedback they received from their members and peers on sexual function after prostate cancer treatment was not necessarily in line with the reported sexual function outcomes reported in clinical studies.6 Therefore, in 2019, Europa Uomo initiated the Europa Uomo Patient Reported Outcome Study (EUPROMS), in which patients were invited to self-report their sexual function, among other items, to provide other patients with information on the impact of prostate cancer treatment. Descriptive statistics of the EUPROMS study have been published previously.6 As sexual function is a key consideration in the decision-making process for prostate cancer treatment, the current study aimed to explore in more detail the self-reported sexual function and use of medications or devices to aid or improve erections of men who were undergoing prostate cancer treatment at the time of survey completion or who had undergone treatment in the past.

Methods

Study design

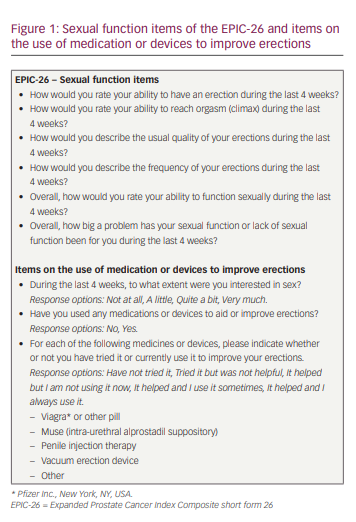

The study design has been described in detail previously.6 In short, men who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and were undergoing treatment (including active surveillance [AS]) at the time of the survey, or who had undergone prostate cancer treatment in the past, were invited to complete the EUPROMS survey. The survey was available via a link placed on the Europa Uomo website (www.europa-uomo.org) and could be completed on a smartphone, laptop or computer, allowing men to complete the questions at home or in another setting in which they felt comfortable. As Europa Uomo is the European prostate cancer patient coalition, with members and supporters across Europe, the EUPROMS survey was available in 19 languages. Each member organization promoted the survey and referred men to the Europa Uomo website to access the questions. The survey included validated measures to evaluate generic health (EuroQoL 5-dimension 5-level), cancer-specific health (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer cancer-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire), and prostate-specific health (Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite short form 26 [EPIC-26]). Furthermore, the survey included questions on the use of medication or devices to improve erections (Figure 1).

Patient-reported outcome measures

The current study focused on the self-reported sexual function of patients, for which the sexual function item data of the EPIC-26 and the outcomes on the use of medication or devices to improve erections were used. The EPIC-26 was designed to evaluate prostate-specific function and bother after prostate cancer treatment.7,8 The EPIC-26 contains five multi-item domains: the four-item urinary incontinence domain, the four-item urinary irritation/obstruction domain, the six-item bowel function domain, the six-item sexual function domain (Figure 1) and the five-item vitality/hormonal function domain. In addition, a single-item measure of overall urinary bother is included. All domains of the EPIC-26 are reported on a 0–100 scale, with higher scores representing more favourable health-related QoL.7,8

Statistical analysis

sand clinical characteristics of the men who completed the EUPROMS survey, as well as to analyse the PRO data of the EPIC-26 and the use of medication or devices to improve erections. R version 3.5.1 was used to perform all analyses.9 Demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as EPIC-26 data and outcomes on the use of medication or devices to improve erections, for the most common treatment modalities reported by the men in our study population were described. For those who underwent a single treatment, these treatments included AS, radical prostatectomy (RP) and radiotherapy (RT). For men who underwent two treatments, the combinations included AS + RP, RP + RT and RT + androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Men who underwent chemotherapy, either as a single treatment or after receiving other treatment(s), were grouped under ‘chemotherapy’. Men receiving miscellaneous single or combination treatments were included in the overall data of PROs, but the numbers were too small to be presented as individual treatment analyses.

Results

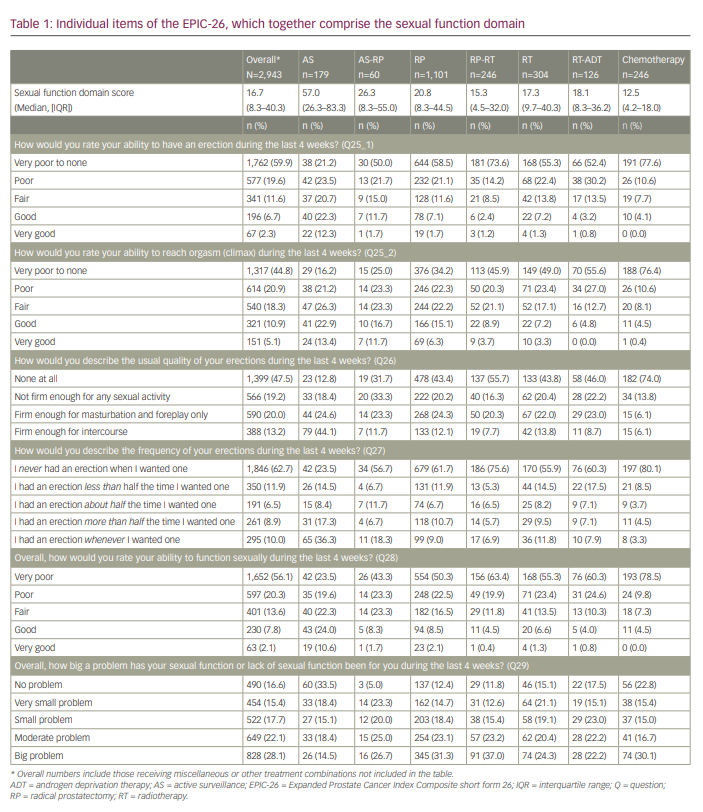

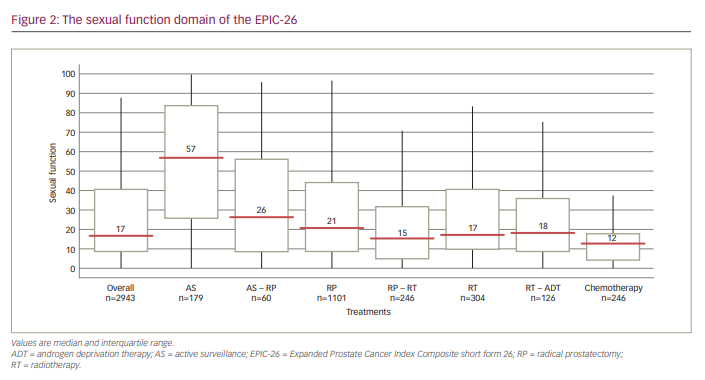

Of the 3,983 men who started filling in the questionnaire, 2,943 (74%) completed all questions. Median age was 71 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 65–75 years), and 81.9% of men were living with a spouse. Table 1 and Figure 2 show the median sexual function domain scores of the EPIC-26. Men on AS self-reported the highest level of sexual function (57.0, IQR: 26.3–83.3) compared with men who underwent RP (20.8, IQR: 8.3–44.5) or RT (17.3, IQR: 9.7–40.3).

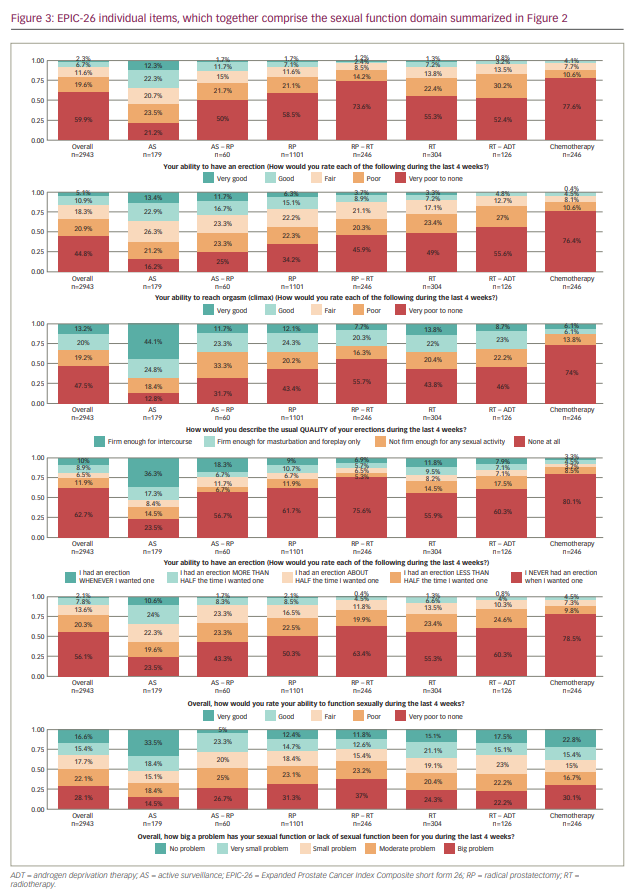

Table 1 and Figure 3 show the data for the individual items of the EPIC-26. Self-reported outcomes for items assessing the ability to have an erection, items asking about the quality and frequency of erections and the bother related to the potential reduced sexual function in men after prostate cancer treatment are shown. The self-reported ability to have an erection varied according to treatment: 44.7% of men on AS reported very poor to none/poor ability versus 71.7–88.2% of men receiving other treatments. Of the men who rated their ability to have an erection as good/very good, 34.7% were on AS, whereas this percentage was lower for other treatments (range: 3.6–13.4%).

When describing the quality of erections, 74.0% of men who had “ever had chemotherapy” reported no quality of their erections at all, compared with 55.7% of men on RP-RT and 12.9% of men on AS. Masturbation and foreplay was possible for 20.3–24.6% of men who underwent active treatment or AS. The percentage of men reporting erections firm enough for intercourse was highest in the AS group (44.1%) and lowest for men undergoing chemotherapy (6.1%).

With respect to the frequency of erections, 80.1% of men who had “ever had chemotherapy” never had an erection when they wanted one, compared with 75.6% of men on RP-RT and 23.5% of men on AS. The ability to have an erection about half or more than half the time they wanted one ranged from 8.2% (“ever had chemotherapy”) to 25.7% (AS).

Overall, men who rated the ability to function sexually as very poor/poor (n=1,652 and n=597, respectively) were 43.1% on AS, 66.6% on AS-RP, 72.8% on RP, 83.3% on RP-RT, 78.7% on RT, 84.9% on RT-ADT and 88.2% had “ever had chemotherapy”. Conversely, of the men who rated their overall ability to function sexually as good/very good (n=230 and n=64, respectively), 34.6% were on AS, 10.0% on AS-RP, 10.6% on RP, 4.9% on RP-RT, 7.9% on RT, 4.8% on RT-ADT and 4.5% on chemotherapy. Of the 1,652 (56.1%) and 597 (20.3%) men who rated their overall ability to function sexually as “very poor” or “poor”, respectively, 13.6% considered this function to be no problem, 11.6% a very small problem, 13.9% a small problem, 24.7% a moderate problem and 36.3% a big problem.

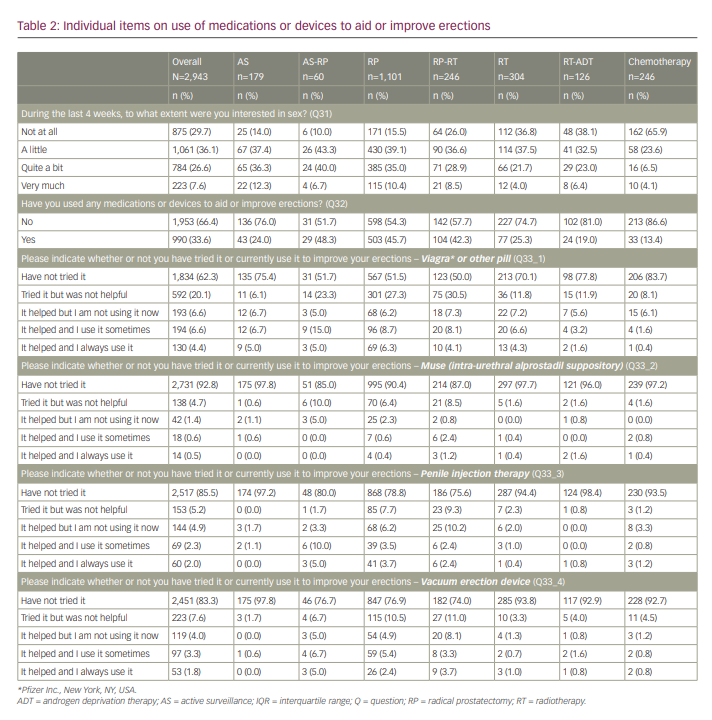

When asked to what extent men were interested in sex (Table 2), men who had “ever had chemotherapy” were the least interested (89.5% not at all/a little), whereas, for the other treatments, the responses were more mixed. Of the men who were not at all interested in sex (n=875), 87.8% did not try any medications or devices, compared with 67.8% of those who were little interested in sex (n=1,061), 47.7% of those who were quite a bit interested (n=784) and 41.3% of those who were very much interested in sex (n=223).

Discussion

The outcomes of the unique, patient-driven EUPROMS study revealed the significant and non-negligible impact of prostate cancer treatment on sexual function. The impact of active treatment on the participant’s ability to have an erection (71.7–88.2% reported very poor to none/poor ability) compared with AS (44.7% reported very poor to none/poor ability) was significant. The ability to reach orgasm was better for men who underwent RP, AS-RP or were on AS (43.6–62.6% of them reported fair/good/very good ability to reach orgasm) compared with men who underwent RP-RT, RT, RT-ADT and chemotherapy (66.2–87.0% of them reported very poor to none/poor ability to reach orgasm). When looking at the overall ability to function sexually, 43.1% (AS), 66.6% (AS-RP), 72.8% (RP), 83.3% (RP-RT), 78.7% (RT), 84,9% (RT-ADT) and 88.3% (chemotherapy) of men rated this as very poor/poor; furthermore, more than half of men who underwent surgery (AS-RP, RP, RP-RT) viewed their lack of sexual function as a moderate or big problem. It was mostly these men who had tried medication or devices to improve their erections.

The results of the EUPROMS study are generally in line with the picture seen in the scientific literature: direct active treatment is associated with greater sexual dysfunction compared with AS as a management strategy.10,11 However, based on the systematic review of Lardas et al.,10 Penson argued in his editorial comment that differences are seen between the sexual function scores reported by single-centre, high-volume centres and those by multicentre, more population-based studies, with single-centre, high-volume centres reporting higher (i.e. better) scores.11 Remmers et al. explored the differences in PROs further by predicting sexual function and urinary incontinence scores based on the age at questionnaire completion from the EUPROMS study.12 A literature review was subsequently conducted to identify clinical studies reporting EPIC or EPIC-26 data at the estimated time interval between diagnosis and questionnaire completion; hence, the review compared the sexual function and urinary incontinence scores between clinical studies and the EUPROMS study. Remmers et al. concluded that a fair share of the clinical studies reported higher scores, which were within the range for the minimal important change of 6–9 points for urinary incontinence and 10–12 points for sexual function, compared with the scores predicted from the EUPROMS data.12,13 This seems to indicate that patients participating in investigator-initiated clinical trials tend to play down their problems related to health-related QoL, compared with patients who self-report their QoL in a more informal setting. However, further research in this area is warranted.

Data from the EUPROMS study can be used in daily clinical practice to inform patients and physicians about the impact of prostate cancer treatment and to engage in a shared decision-making process. When discussing the sexual function domain and what patients can expect after prostate cancer treatment, erectile (dys)function often receives the most attention, especially for men undergoing RP.14 Sexual function is, however, a multidimensional concept that includes many more aspects, such as libido, erection, orgasm and sexual satisfaction. Albers et al. found that men’s sexual desire level before undergoing prostate cancer treatment also plays an important role in their sexual satisfaction after treatment.14 In patients undergoing bilateral nerve-sparing RP, it has been observed that reaching the baseline preoperative erectile function postoperatively is not always sufficient to obtain patient satisfaction.15 Even if erectile function is preserved, there are other changes that could occur due to prostate cancer treatment that may affect sexual function and sexual satisfaction.16–18 In a study of 884 men who had no erectile dysfunction before undergoing robot-assisted RP (RARP), a mean preoperative satisfaction score (calculated by summing the scores of two items of the 15-item International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire) of 8.4 (range: 2–10; standard deviation [SD]: 1.7) was recorded.14 For those men who experienced erectile dysfunction after RARP, these mean satisfaction scores decreased significantly to 4.8, 4.8, 4.9 and 4.6 (range: 2–10; SD: 1.7–2.5) at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months of follow-up, respectively. Men who did not experience erectile dysfunction after RARP reported post-RARP mean satisfaction scores ranging from 8.1–8.4 (range 3–10, SD 1.4–1.6) between 6 and 36 months of follow-up, respectively. In multiple logistic regression analysis, the authors found that preoperative satisfaction was more important for postoperative sexual satisfaction than erectile function at baseline or at 24- or 36-months of follow-up.14 In the EUPROMS study, the EPIC-26 measure was used, and it included a question on the potential bother experienced due to (lack of) sexual function. Men in the EUPROMS study who had undergone RP reported a median sexual function score of 20.8 (IQR: 8.3–44.5). In this same group of men, 54.4% viewed their sexual function as a moderate or big problem. It can be hypothesized that the men who viewed their lack of sexual function as a moderate or big problem were the same men who were not sexually satisfied. This hypothesis might be further supported by the fact that most of these men indicated to be interested in sex (“quite a bit” or “very much”) and tried medications or devices to improve their erections. The studies reflected upon above only included patients treated with RARP, and therefore, the results may not be representative of other treatment modalities.14 However, these studies suggest that counselling patients preoperatively about sexual function in its broadest form (i.e. libido, erections, orgasms, sexual satisfaction) and the impact of prostate cancer treatment on sexual function may present patients with more realistic expectations of sexual function after treatment. Therefore, while the EUPROMS study is already providing patients and physicians with more realistic data on erectile function, which can be used to help make more informed decisions on treatment, men may also be able to increase their overall sexual satisfaction further after treatment by considering and discussing upfront other elements of sexual function during the decision-making process. Appropriate counselling conveying that a man’s sexual life and sexual joy do not have to be over when erections become an illusion could be of great value for some groups of patients.

Some limitations of the study should be considered. First, no pretreatment PRO data were available for the study cohort. However, Europa Uomo did not intend to design the study to include a pretreatment measurement and was instead interested in how patients experience their QoL after prostate cancer treatment at the time of questionnaire completion. Second, the effect of age was not considered when analysing sexual function in the men who completed the survey. It is known from the Massachusetts Male Aging study,19 and described in the European Association of Urology Guidelines 2020 on Sexual and Reproductive Health,20 that impotence and erectile dysfunction affect men of all ages and ethnicities in the general population and that the risk increases with age. The impact of prostate cancer treatment is an additional factor. Conversely, the strengths of the EUPROMS study include the large sample size of nearly 3,000 men from all over Europe, thus representing the high diversity in the quality of care received. Furthermore, the survey included a combination of generic, cancer-specific and prostate cancer-specific validated PRO measures. Finally, men could complete the EUPROMS survey in full anonymity, which is likely to have positively affected the openness and honesty of their responses, allowing them to fully share their day-to-day experiences in the sexual function domain.

Conclusion

The EUPROMS study, in which 2,943 patients shared their experiences to inform future patients about the impact of prostate cancer treatment on QoL, showed that the impact of prostate cancer treatment is significant and non-negligible. The ability to have an erection was much lower in men after treatment than in men on an AS management strategy. Looking at the overall ability to function sexually, 66.6–88.3% of the men who received active treatment rated it as ‘very poor/poor’. More than half of the men who underwent surgery viewed their lack of sexual function as a moderate or big problem for which they used medications or devices. These data from the EUPROMS study can be used in daily clinical practice to guide the preference-sensitive decision-making process for patients newly diagnosed with prostate cancer.