When there was only one drug (mitoxantrone) approved for use in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), chemotherapy played a marginal role in the treatment of these patients, since two large randomised studies1,2 and one Phase III study3 had demonstrated that while it provided significant control of symptoms, it failed to improve survival rates.

When there was only one drug (mitoxantrone) approved for use in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), chemotherapy played a marginal role in the treatment of these patients, since two large randomised studies1,2 and one Phase III study3 had demonstrated that while it provided significant control of symptoms, it failed to improve survival rates.

Tannock et al. assessed its efficacy in patients with symptomatic CRPC, and showed that, in combination with prednisone, mitoxantrone significantly improved palliative responses (29 % vs 12 %; p=0.01) and duration of palliation (43 versus 18 weeks; p<0.0001) by comparison with prednisone alone.1 The second randomised study was conducted by Cancer and Leukemia Group B, and showed that the combination of mitoxantrone and hydrocortisone delayed disease progression by comparison with hydrocortisone alone, but without improving overall survival (OS).2

The small Phase III study involved patients with asymptomatic CRPC and found that mitoxantrone plus prednisone induced a significantly superior biochemical response rate in comparison with prednisone alone (48 % versus 24 %; p=0.007), but failed to lead to any advantage in terms of the median time to treatment failure, the median time to progression, or median survival.3

On the basis of these results, even though mitoxantrone was the only approved drug for the palliative treatment of CRPC, chemotherapy was rarely proposed to patients. This changed in 2004, when it was found that docetaxel offered significant advantages over mitoxantrone in terms of both symptom control and survival.4,5 The Phase III TAX 327 trial4 randomised 1,006 CRPC patients with stable pain levels to receive three-weekly treatment with docetaxel plus prednisone, or weekly treatment with docetaxel plus prednisone, or mitoxantrone plus prednisone. By comparison with mitoxantrone plus prednisone, three-weekly docetaxel plus prednisone improved median survival (18.9 versus 16.5 months; p=0.009), and increased the proportions of patients with a ≥50 % reduction in prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels (45 % versus 32 %; p<0.001), a reduction in pain (35 % versus 22 %; p=0.01), and improved quality of life (22 % versus 13 %; p=0.009). The results of a four-year extended follow-up study showed that three-weekly docetaxel maintained its advantage over mitoxantrone in terms of OS (19.2 versus 16.3 months; p=0.004).6

The SWOG 99-16 trial randomised patients with metastatic CRPC to docetaxel plus estramustine or mitoxantrone plus prednisone. Once again, docetaxel prolonged median OS (17.5 versus 15.6 months; p=0.02) and the median time to progression (6.3 versus 3.2 months; p<0.001), and increased the proportion of patients with a ≥50 % reduction in PSA levels (50 % versus 27 %; p<0.001).5

On the basis of these findings, a course of docetaxel-based chemotherapy became the treatment of choice for patients with CRPC. In everyday clinical practice, however, the drug is not administered until disease progression, or the achievement of the best response, because of its toxicity profile, and patients receive a limited number of courses (usually no more than 8–10, as in the pivotal studies) in the absence of progression.

The protocol for the TAX327 trial was completed by 35 % of the patients receiving the planned courses of treatment in the weekly arm, and by 46 % of those in the three-weekly arm.4 This reflects the findings in clinical practice that some patients respond to docetaxel and discontinue treatment after receiving the planned courses without experiencing disease progression. However, the response is not durable, and all of the patients who discontinue first-line chemotherapy in the absence of progression eventually relapse. In the SWOG trial, the time to progression was 6.3 months5 and in the most successful arm of the TAX327 trial, the duration of the PSA response was 7.7 months.4 This type of finding is common to all kinds of advanced cancers: systemic treatment controls the disease only temporarily, meaning that further lines of therapy are required. The need for additional treatment options is more urgent for oncology patients who fail to achieve disease control with first-line therapy and require different drugs.

In the case of CRPC, the problem of the lack of a second-line therapy became increasingly relevant after docetaxel became the cornerstone of first-line treatment, because many docetaxel-resistant patients require further treatment and therapeutic options for nonresponders were very limited. Mitoxantrone is only moderately active as second-line treatment, with biochemical response rates of 6–20 %,7–10 and the new-generation drugs have failed to improve patient survival.9,11 Some studies have explored the possibility of overcoming docetaxel resistance by adding a second drug, but often at the cost of an unmanageable toxicity profile.12–14 Two large-scale randomised phase III trials have recently tested the efficacy of new drugs that are expected to become available during 2012 as second-line treatment after docetaxel failure. Cabazitaxel is a new taxane associated with better survival rates than mitoxantrone15 and abiraterone is a new cytochrome 17 alpha-hydroxylase – C(17,20)-lyase (CYP17) – inhibitor that was superior to placebo in terms of survival.16

The scenario for patients who fail to respond to first-line docetaxel has been very discouraging. On the other hand, although it is clear that their docetaxel sensitivity is different from that of those who stop first-line treatment because of disease progression, all of those who respond will experience disease progression some time after discontinuing docetaxel. In these cases, the question is whether they are still sensitive to docetaxel when they relapse: in other words, is it possible to repeat docetaxel-based treatment and achieve a new response capable of prolonging disease control?

Rationales for Chemotherapy Rechallenges and Intermittent Therapy in Oncology

Rechallenges refer to all situations in which a systemic treatment is resumed in the hope of exploiting its potential activity after it has been discontinued because of the completion of the planned number of courses (usually determined on the basis of median cumulative toxicity) and not because of the development of resistance (disease progression).

The strategy is strictly related to the concept of the sensitivity/resistance of a specific tumour to a specific drug, and has been particularly applied in the case of ovarian cancer. The standard first-line chemotherapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer is a combination of paclitaxel and a platinum analogue (cisplatin or carboplatin), which is usually administered for not more than six courses in the absence of progression. Upon relapse, patients with a progression-free interval of more than six months are considered platinum sensitive, and platinum-based retreatment can lead to an additional 30–50 % response rate.17 Patients who have experienced a progression-free interval of less than six months are considered platinum resistant, and the reintroduction of platinum should not be considered. Similarly, a platinum-based rechallenge can be proposed for patients with advanced small cell lung cancer and a progression-free interval of at least three months after discontinuation of first-line treatment.18

In the case of a true intermittent strategy, chemotherapy is stopped for a defined period of time after the administration of a limited number of cycles, and then resumed in an attempt to reduce toxicity and improve patient compliance. It would probably be more appropriate to use the word ‘rechallenge’ when speaking of a situation in which a patient who has completed a predefined number of chemotherapy courses without experiencing disease progression subsequently progresses after any period of time and then receives another course of the same treatment. As the two terms have often been used interchangeably, it may sometimes be difficult to identify which strategy has been used in a given study.

A number of randomised studies have tested an intermittent/ rechallenge strategy in patients with metastatic breast cancer19–22 or metastatic colorectal cancer.23–26 Although the results of these studies conflict in terms of the quality of life advantages for intermittent over continuous therapy, and their equivalence in terms of disease control, they provide evidence that a new response may be achieved when treatment is resumed. For example, the patients with metastatic breast cancer who received cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil and epirubicin (FEC) at the time of progression after four courses of the same combination showed an overall response rate of 41 %,22 and the patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who resumed treatment with fluoropyrimidines achieved a response in 21 % of cases.23

The rechallenge and intermittent strategies may hypothetically delay the appearance of drug resistance.

Rechallenges and Intermittent Therapy in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer

In the absence of an active second-line treatment for CRPC, it was debated whether the patients responding to first-line docetaxel who discontinued the treatment without experiencing progression would still be sensitive to docetaxel or not.

In prostate cancer, the concept of intermittent treatment developed in the context of advanced hormone-sensitive disease. Patients with hormone-sensitive disease undergo androgen deprivation for extended periods of time but, as this leads to a number of side effects that impair their quality of life, phase II and phase III studies were designed to investigate a strategy in which treatment was stopped after prolonged PSA normalisation and resumed at the time of biochemical progression (usually PSA values of 10–20 ng/ml). This approach has led to improved tolerability and quality of life27 but, because of the limited availability of mature data concerning OS, conflicting conclusions have been drawn as to whether intermittent androgen deprivation should be considered experimental28 or not.29 However, as androgen deprivation in the intermittent strategy is not discontinued after a pre-planned treatment duration but once a biochemical response is achieved, and is resumed at the time of biochemical progression, it would be more appropriate to call it a rechallenge.

In the field of CRPC, a truly intermittent strategy with planned early treatment interruption followed by a predefined rest period designed to improve patient compliance and their quality of life was used in a randomised Phase II trial. In that study, 145 patients were assigned to receive eight consecutive courses of docetaxel with or without estramustine, or four courses of docetaxel with or without estramustine followed by a three-month rest period before receiving a further four courses. The recently presented preliminary results showed a similar quality of life profile in both arms.30

Although in this case it was called ‘intermittent’, the rechallenge strategy was used in a Phase II study conducted by the Austrian Urology Oncology group (AUO AP 33/02). In this study, chemotherapy was stopped after a planned number of courses and resumed at the time of disease progression. Preliminary findings were presented in 2003 and 2005,31,32 but the final report has yet to be published. Seventy-five patients received weekly treatment with docetaxel and estramustine, which was stopped after three months in the absence of disease progression; 40 patients resumed chemotherapywhen their PSA levels doubled (relative to the nadir value) or when progression was suspected for other reasons. Multiple resumptions were allowed. Patients who resumed treatment once, twice and three times had a PSA response in 80 %, 57 % and 29 % of cases, respectively. With a median follow-up of 9.1 months, the median OS of the retreated patients was 18.9 months. On the basis of the results of this trial, the same group planned a Phase III trial comparing intermittent and continuous chemotherapy (AUO AP 40/04), which is reported as having been stopped early on the group’s website.

Two trials have assessed the feasibility and activity of combined high-dose calcitriol and docetaxel in patients with CRPC.33–35 Patients showing a ≤50 % reduction in PSA and serum PSA ≤4 ng/dl were eligible for a rechallenge. Chemotherapy was resumed after a confirmed PSA increase of ≥50 % and a serum PSA value of ≥1–2 ng/dl, or any other evidence of disease progression. In the case of further responses, multiple rechallenges were allowed. The 2004 report of the preliminary Phase II trial described eight patients who underwent at least one rechallenge (four underwent one, two underwent two, and two underwent three), and showed a biochemical response rate of 57 %.33 A second Phase III trial was prematurely ended because an interim analysis revealed an excess of deaths in the calcitriol arm.35 A specific report was published concerning the outcomes of patients undergoing the first rechallenge in this Phase III trial, who achieved a biochemical response rate of 45.5 %;36 however, this mainly concentrated on the length of the chemotherapy holidays and did not specifically discuss the clinical and toxicity outcomes of a rechallenge strategy; furthermore, the trials were not designed to evaluate the rechallenge but simply allowed the possibility of retreating responders to first-line docetaxel.

The first prospective study of a rechallenge strategy was published by Di Lorenzo et al.37 who chose a five-month cut-off period before proposing the rechallenge to patients who had not progressed during first-line docetaxel. The rechallenge was limited to a single course even in the case of a new response to treatment. Rechallenge treatment was also continued until progression, which may explain the toxicity profile (24.5 % of patients with grade 3–4 neutropenia and 11.1 % with grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia). Furthermore, only 24.5 % of patients experienced a 50 % reduction in PSA levels.

An ongoing randomised trial is testing the potential role of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) administration during a chemotherapy holiday for patients who have responded to six courses of docetaxel. Preliminary (and not conclusive) results concerning 42 patients have recently been published.38

Over the last few years, a number of authors have published data provided by their everyday experience of docetaxel rechallenge at the time of progression after first line treatment, thus making it possible to assess the feasibility and activity of this strategy. Although some papers describe very small patient series,39,40 others describe larger populations.

Eymard et al. retrospectively reviewed the cases of 50 patients, 48 % of whom had undergone a rechallenge as third- or fourth-line treatment; the biochemical response rate was 48 % and toxicity was manageable.41 Another French retrospective study proposed a single docetaxel rechallenge for 39 patients, frequently as third-line or later treatment (74 %).42 As a result, the biochemical response rate (defined as a >50 % reduction in PSA levels) was only 38 %, but median survival after the rechallenge was 15.8 months.

This group has reported data concerning 46 patients who were considered to be docetaxel-sensitive because they responded to docetaxel-based first-line chemotherapy and discontinued the treatment without experiencing disease progression.43 All of these patients underwent a first rechallenge and the responders continued to be considered docetaxel sensitive and capable of undergoing further rechallenges unless contraindications appeared during the treatment holiday (e.g. inadequate performance status, new comorbidities) or unless they had experienced unacceptable toxicities during the rechallenge. Subsequent rechallenges were proposed until the appearance of real docetaxel resistance: i.e. disease progression during docetaxel treatment. The rechallenge usually involved no more than 4–6 courses of docetaxel. The overall biochemical response rate was 66 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 56–76) with a very limited number of major toxicities. After a median follow-up of 25 months, median duration of OS in the total population was 32 months from the start of first-line therapy (95 % CI 25–39), and 18 months from the start of the first rechallenge (95 % CI 13–23). The projected 2-year OS rate from the first docetaxel administration was 77.5 % (95 % CI 64.4–90.5).

Although they assessed only a small sample of patients, Mountzios et al. provided interesting data concerning a comparative evaluation of the patients’ quality of life during the periods on and off chemotherapy. They found that drug holiday allows patients to recover from the side effects of chemotherapy and produces a feeling of well-being that can have a beneficial effect on the patients’ cognitive, emotional and social state.44

Additional data concerning the safety and tolerability of a rechallenge in patients older than 69 years have been provided by Gernone et al.45 Also, a retrospective study of 31 patients found that a rechallenge using a weekly schedule can produce a biochemical response in patients who had progressed on a three-week schedule.46 Likewise, Caffo et al. found that a rechallenge with weekly docetaxel seems to be able to control the disease in patients previously treated with the three-week schedule.43

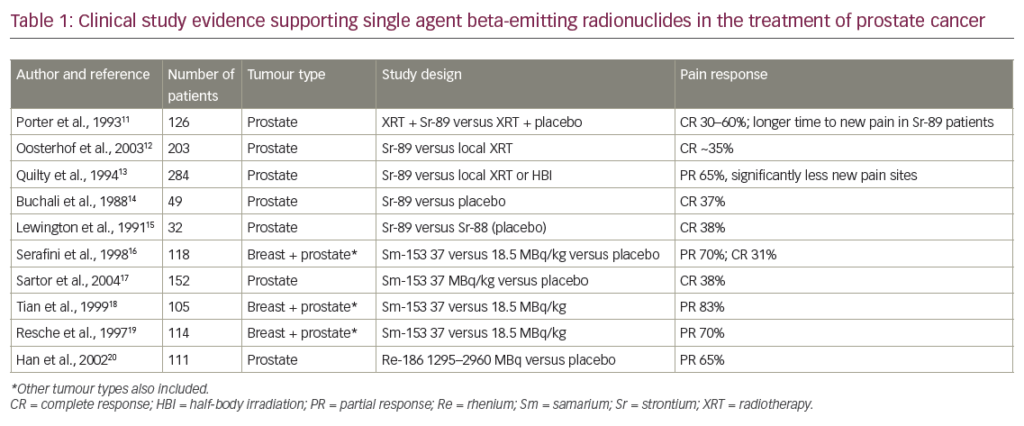

Table 1 summarises the findings of all of these studies along with some data that are currently only available in abstract form.

Various strategies have been used to reintroduce docetaxel after first-line treatment. Excluding the true intermittent treatments (in which patients received ‘incomplete’ first-line therapy with the aim of reducing drug exposure and, consequently, its potential side effects), the authors used one or more rechallenges. In the case of a single rechallenge, docetaxel was either administered until disease progression or in a limited number of courses. The findings of the studies described in full papers suggest that it is safe to propose multiple rechallenges provided that the number of courses is limited each time,43 whereas the rechallenge strategy in which patients receive docetaxel until progression seems to be burdened by greater haematological toxicity.37 Furthermore, when a docetaxel rechallenge is planned after subsequent lines of therapy, it seems to be less active.41,42

These findings were relevant in the past, given the characteristics of the CRPC patients who underwent rechallenge: although they were frequently old and affected by multiple comorbidities, they were also fit, tolerated first-line chemotherapy well and achieved disease control. As a consequence they requested further treatment albeit with non-curative intent. Any proposed treatment should therefore be well tolerated and active, but have no negative impact on quality of life. The findings are even more relevant today, however, given the availability of another chemotherapeutic agent that is active in second-line therapy. A docetaxel rechallenge is well tolerated (particularly if the number of courses for each rechallenge is limited) and can be proposed several times. Cabazitaxel toxicity can be easily managed on the basis of its profile (characterised by neutropenia and diarrhoea), and has a clear survival advantage over mitoxantrone.15

Factors Predicting a Response to a Rechallenge

Docetaxel rechallenges have so far been proposed in response to an unmet clinical need arising from the lack of second-line chemotherapy for CRPC patients. It is possible, however, they may allow for more prolonged disease control than that found in pivotal trials. When cabazitaxel and abiraterone (which are efficacious in a second-line setting) are available in everyday practice, questions may be asked about the best strategy for patients responding to first-line docetaxel – should they undergo a docetaxel rechallenge (in order to postpone the use of the new drugs until the appearance of docetaxel resistance), or should they receive the new drugs immediately?

In other settings in oncology, progression-free survival after completing first-line therapy is usually considered the only variable capable of distinguishing drug sensitivity and drug resistance: patients with ovarian cancer are considered to be sensitive to platinum if no progression is observed for at least six months,47 and those with small cell lung cancer are considered to be sensitive if no progression is observed for three months.18

In the case of CRPC, one study of a series of patients treated with a single rechallenge suggested an arbitrary cut-off period of five months as a means of identifying the patients who are sensitive or resistant to docetaxel,37 while Loriot et al.42 found that an interval of more than three months from the previous docetaxel course was associated with prolonged progression-free and overall survival. However, these authors did not assess further variables, and did not specify the criteria defining these cut-off times.

The findings of an analysis of the factors capable of predicting the response to a rechallenge have recently been published in abstract form, and showed that a 30 % decrease in PSA levels at the time of the first rechallenge correlated with a longer treatment holiday after first-line treatment (a mean of 28 weeks in responders and 19 weeks in non-responders, p=0.04) and a higher percentage increase in PSA levels during the first treatment holiday (a mean of 848 % in responders and 341 % in non-responders; p=0.02). Unfortunately none of these (or, indeed, other parameters) correlated with the response to a second rechallenge.48

Our group has provided the most complete analysis of predictive factors published to date. It is based on data relating to 92 consecutive rechallenges in 46 patients.43 For each rechallenge course, the following variables were evaluated as potential predictors of response:

- treatment schedule (three-weekly versus weekly);

- estramustine administration (yes or no);

- PSA response to the previous docetaxel course (a 50 % reduction in comparison with baseline, yes or no);

- baseline parameters (haemoglobin and alkaline phosphatase levels, presence of pain, ECOG performance status);

- the number of previous docetaxel courses;

- PSA parameters (slope log, doubling time, and velocity);

- previous docetaxel course and treatment holiday; and

- duration of the treatment holiday before the rechallenge.

The PSA parameters were calculated on line at the website of MSKCC (http://www.mskcc.org). Univariate analysis showed that the PSA response to the previous docetaxel course, the duration of the preceding treatment holiday (≥23 weeks), PSA doubling time during the previous docetaxel course, and a PSA slope-log of ≥0.62 during the preceding treatment holiday predicted response, and multivariate analysis confirmed the predictive value of the PSA slope-log interval, the duration of the preceding treatment holiday, and the response to the previous cycle. A predictive score was obtained by assigning one point to each factor when it was present before the start of the rechallenge. In the rechallenges, patients with baseline scores of 3, 2 and 0–1 had biochemical response rates of, respectively, 100 %, 86 % and 32.3 %. Given these clear differences in biochemical response rates, it seems to be reasonable to propose a rechallenge when at least two predictive factors are present at the time of progression; otherwise a true second-line treatment appears to be a better choice.

Conclusions

Although the strategy of a docetaxel rechallenge for CRPC patients was developed simply to cover the practical clinical need of what to do when fit patients progress after discontinuing first-line therapy, a number of studies have demonstrated that it can be safely administered more than once, and can lead to prolonged disease control. The chemotherapy holiday may improve patient compliance by allowing recovery from treatment-related toxicities and improvement in the quality of life. Furthermore, the strategy can reduce drug exposure and cumulative toxicity. When drugs that are active as second-line treatments become available, a rechallenge may still play a role in a subset of patients, and identifying predictive factors can help in choosing the most appropriate treatment. ■