Esophageal cancer is one of the deadliest cancers, and its incidence is on the rise worldwide.1 In the United States, an estimated 16,980 cases of esophageal cancer were diagnosed in 2015 and 15,590 deaths are expected from the disease. With the latest advances in multimodality approaches, the five-year survival rate has risen only to a mere 17.9%.2 Two main types of esophageal cancers are commonly known, i.e., squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, and these may have some similar and some different risk factors. Squamous cell type is the most common subtype worldwide, but in the US its incidence is declining whereas adenocarcinoma is now the most common type.1 The rising rate of adenocarcinoma in the US is thought to be due to corresponding high incidence of Barrett’s esophagus.3

Various risk factors are associated with esophageal cancer, including smoking, alcohol, socioeconomic status, and caustic injury, history of thoracic radiation, demographic features, obesity, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).4–9

The characteristic presenting symptoms of esophageal cancer are mainly dysphagia and/or odynophagia. Other symptoms may include, but are not limited to, chest or upper abdominal pain/discomfort, regurgitation, weight loss, loss of appetite, hematemesis, dyspepsia, hoarseness, chronic cough, vomiting, and cervical lymphadenopathy.10 Patients with a history of GERD may be found to have Barrett’s esophagus on routine follow-up, which further needs follow-up because of high risk for the developing

adenocarcinoma.11 Incidentally, asymptomatic or symptomatic localized intraepithelial neoplasia may also be found, which when detected has excellent prognosis as compared to the more advanced stages of this disease.12 At the time of presentation and diagnosis, the patient usually has at least one of the aforementioned symptoms, at least in the cases that we have seen in our experience. In at least 50% of cases, at diagnosis tumor has invaded/spread to nearby vital structures or metastasized, lung and liver being the most common locations.13 But the primary symptoms are always seen, and correlate with the T stage of disease, which is best assessed with an esophageal ultrasound (EUS).14

We report a patient who presented with advanced/stage IV esophageal cancer, with no local/upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

Case Report

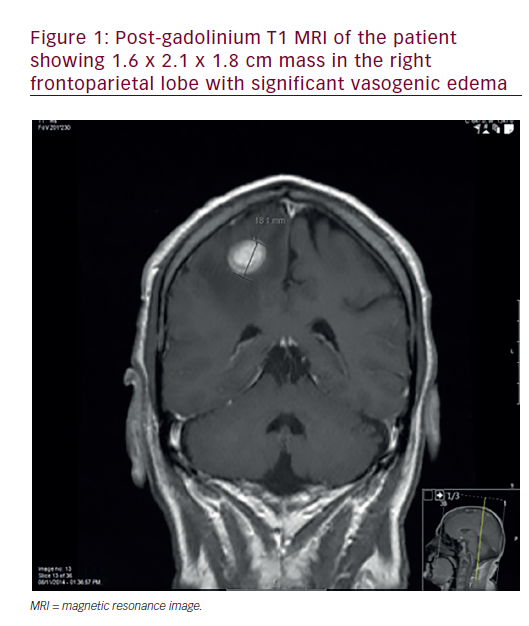

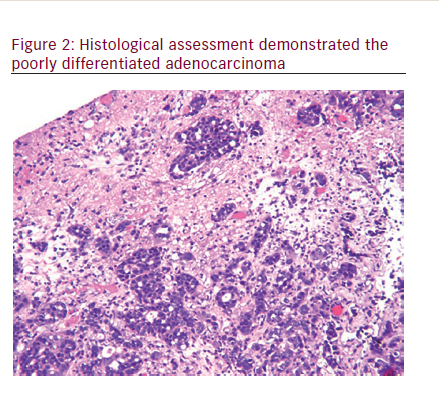

A 68-year-old male presented with sudden onset of shaking and weakness of the left upper and lower limb. This was associated with occasional headaches for a few weeks. Patient had a history of type 2 diabetes and hypercholesterolemia. Considering his age and medical history, the most likely cause of that was suspected to be a cerebrovascular event. Upon further workup, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head demonstrated a mass, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan confirmed a 1.6 x 2.1 x 1.8 cm mass in the right frontoparietal lobe with significant vasogenic edema(Figure 1). CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative for any other masses. Referral to neurosurgery was done, and the mass was removed. The histology was conclusive for an adenocarcinoma. The tumor cells react with antibodies to cytokeratin 7, but not with antibodies to cytokeratin 20, prostate specific antigen, prostatic acid phosphatase and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) (Figure 2).

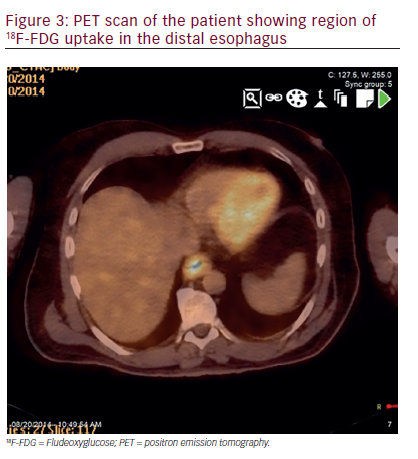

This antigen profile suggested origination of the primary tumor either within the lung or upper GI tract. The patient was scheduled for further oncological work-up. Post-operative staging, including CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was unremarkable. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed an area of increased metabolic activity along the distal esophagus, which corresponded to a segmental esophageal wall thickening on CT (Figure 3). Endoscopy with esophageal ultrasound (EUS) detected a T3N1M1 primary tumor. EUS-guided cold-forceps biopsy of the mass, when compared to the brain metastasis, confirmed a HER-2 negative adenocarcinoma. Following neurosurgery for tumor resection, the patient had prolonged stay in the hospital because of post-operative

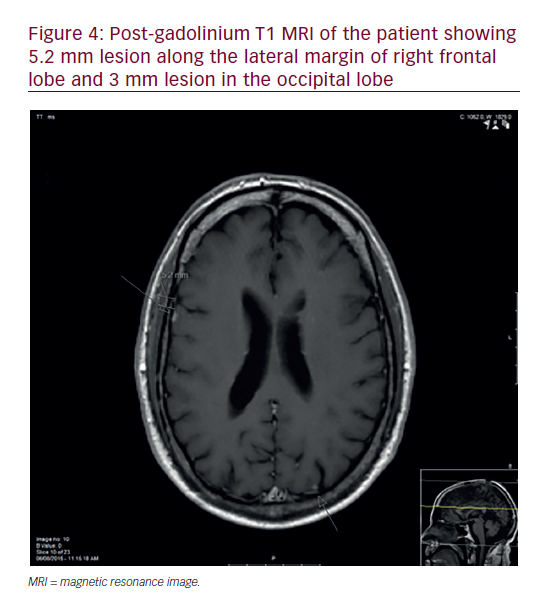

cerebral abscess. Subsequently, he received adjuvant cyberknife based hypofractioned radiotherapy in five treatments to the area of the resected tumor mass. Upon presentation to medical oncology, a repeat PET scan showed new lesions in retroperitoneum, liver and thoracic spine. Palliative chemotherapy with folinic acid + 5-FU + irinotecan (FOLFIRI) was chosen. Platinum based therapy was avoided in view of his already poor neurological status. He has yet to complain of dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain, nausea, vomiting or other symptomology, otherwise typical of the disease that he has. Repeated MRI of brain in six months revealed multiple bilateral metastatic lesions and patient was referred for whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) (Figure 4).

Discussion

Esophageal cancer presents as a highly lethal malignancy with a poor prognosis.21 Patients usually presents with typical symptoms of dysphagia and odynophagia, and may have associated dyspepsia, chest pain, hoarse voice, and other subjective upper GI symptoms. These symptoms engender a work-up, especially if the patient has a history of heavy smoking or and drinking, old age, history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), associated unintentional weight loss, and thus help us suspect and find or rule out an esophageal etiology.

However, as seen the aforementioned example, esophageal cancer may present with atypical symptoms, such as those suggestive of cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Esophageal cancer may remain undiagnosed until it becomes metastatic/Stage IV disease, and may show up as a different presentation altogether, depending upon the location of the metastatic focus/foci. Liver, lungs, bone, and adrenal glands are the most common sites of distant metastases in patients with esophageal cancer, while incidence of brain metastasis is 1.5%.20

Metastatic brain tumors account for approximately 20–40% of all intracranial masses in adults. Their common clinical manifestations are gait disturbances, altered mental status or personality changes, and focal neurologic deficits.19 Brain metastasis as the presenting form of esophageal cancer are highly uncommon and have been found in only 1.7–3.6% of patients with different types of esophageal cancer.15–17 In the United States, adenocarcinoma is the most common pathologic type of the brain metastasis from esophageal cancer. Surgery with or without WBRT presents the most common treatment modality. The median survival time from the diagnosis of brain metastasis was eight months with median patient age >60 years.18

Patients with advanced age may have several comorbidities and are at high risk for GI cancers. As learned from this case, a stroke like presentation may be a complication of metastatic disease from a GI primary and esophageal cancer can present in this fashion as symptomless primary disease. Follow up of stroke or any functional brain disease should include proper imaging and pathological studies to find out the cause, keeping cancer of the esophagus/upper GI tract as one of the causative possibilities.

The case reported in the present study is exceptional due to the absence of typical esophageal disease symptoms. It remains a subject of discussion as to whether there is a particular variety/subtype of esophageal cancer that has a potential to present this way, or if this is just one of those rarest cases.