Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare malignancies in children and adolescents. They represent only 7.4 % of cancer cases in children <20 years of age, with 850–900 new cases diagnosed each year in the US. By comparison, leukemia represents 25 % of cancer cases in the same age group and there are 3,250 new cases per year in the US.1

While in general survival for soft-tissue sarcoma is better in children than in adults,2,3 there are special considerations when treating children. Relapse can occur at any time and very late relapse is possible as children live longer. The definition of ‘cure’ thus becomes difficult in many aspects of these patients’ lives.4 Survival after relapse is associated with a particularly poor prognosis, especially in rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) and distant relapse in non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcomas (NRSTS).5–10 Treatment of pediatric sarcoma may have several deleterious effects. End-organ failure can occur due to cardiotoxicity from doxorubicin or renal failure and infertility due to ifosfamide therapy, for example.11

Secondary malignancies may result from treatment of the primary tumor and are associated with a poor outcome. This occurred in 15.8 % of patients with soft-tissue sarcoma in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry,12 where higher risks were associated with prior radiation and alkylating agents as part of the treatment for the primary tumor. Late effects may affect performance in simple activities of daily living, even when no noticeable physical impairment is present.13 Future long-term studies will assuredly help to define more late effects and help with guidance for monitoring these patients into adulthood. Soft tissue sarcomas are generally categorized into RMS and NRSTS. The former are by far the most common histology.1Rhabdomyosarcoma

RMS is more common in younger children and represents nearly 50 % of soft-tissue sarcomas in children under 14 years of age. The incidence in this age group is 4.6 per million.1 Since RMS is a malignant tumor arising from primitive mesenchymal cells, it can occur in almost any site in the body. Extremity location represents about 20 % of RMS.6–10 Treatment of RMS involves a multimodality approach combining chemotherapy, radiation and surgery. Co-operative group trials have been invaluable in progress toward improved patient survival and in defining prognostic factors to determine risk groups. The Intergroup RMS Study (IRS) Group was formed in 1972 and has completed four such trials: IRS I–IV.6–10 This work continues with the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) in North America and its European counterparts, including the European Paediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Group.

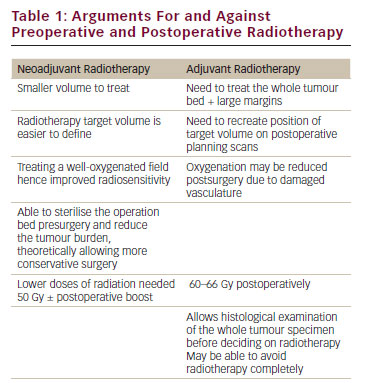

Overall survival at five years for RMS has improved from 49.2 % in 1975–1979 to 62.8 % in 1995–1999 using SEER data.14 In the succeeding IRS, survival improved from 55 % in IRS I, to 63 % in IRS II, to 69 % in IRS III, and to 73 % in IRS IV.6–10 Prognosis is dependent on several tumor and patient characteristics and these have led to the current clinical and staging systems. The adequacy of surgical resection, presence of regional lymph node involvement, and distant metastatic disease were recognized as key prognostic factors early in these studies. These factors led to the clinical grouping system (see Table 1).6,7,15 The importance of the site, invasiveness, and size of the primary tumor were also recognized. This, along with the need for a pre-treatment assessment system, led to a modification of the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system,16 which has been used prospectively since IRS IV9 (see Table 2).

Histological subtype was also found to be significant (embryonal RMS [ERMS] overall has a better prognosis than alveolar RMS [ARMS]) and was incorporated into a risk-based grouping that is used in current studies.10,17,18 The low-risk group includes ERMS group I, II, and III stage 1 tumors. This group represents 30 % of patients, with a five-year overall survival of 95 %. The intermediate-risk group is made up of ERMS group III stage 2 and 3 and group IV patients <10 years of age as well as ARMS histology tumors in groups I–III; this group accounts for up to 60 % of patients, and overall survival is 50–65 %. The high-risk group comprises patients in group IV, who represent 15 % of RMS cases and have a 30 % overall survival at five years.19 Other factors affecting clinical outcome have also been identified. Age less than one year or greater than nine years is associated with worse overall survival than children with RMS who are between one and nine years of age.20 Having more than two metastatic sites is associated with a poorer prognosis in EMRS,10 as is anaplasia on histology.21 The PAX3–FKHR gene fusion identifies a very high-risk subgroup in ARMS, while PAX7–FKHR fusion is associated with a more favorable outcome in other ARMS subgroups.22 In both ERMS and ARMS, bone marrow metastases indicate a very poor prognosis23 and solitary lung metastasis is not associated with improved survival.24

Rhabdomyosarcoma in Extremities

RMS arising in an extremity is associated with many of the factors that portend a poor prognosis. The majority of extremity RMS is the alveolar subtype: 47 % in IRS I and 71 % in IRS IV.25,26 These tumors often present with a higher stage and more frequent nodal involvement (42 % in IRS IV).26

Patients with extremity RMS tend to be of all pediatric ages, including the higher-risk adolescent group. Extremity RMS is thus associated with poorer overall survival, and little improvement has been made over time: 77 % three-year overall survival in IRS II,27 74 % in IRS III,28 and 70 % in IRS IV.26

Within clinical groups, extremity RMS is often associated with a poorer prognosis than RMS patients overall, especially in groups II–IV. In IRS III, five-year survival for group I extremity RMS was 95 %, while survival for group I overall was 93 %. Group II extremity survival was 67 %, although overall survival for group II was 81 %. Extremity survival in group III was only 58 %, while overall survival for group III was 73 %. Thirty-three percent of patients in group IV extremity RMS survived, and overall survival was even lower for group IV at 30 %.26

Prognostic factors for clinical outcomes within the group of patients with RMS of the extremity have varied slightly among IRS studies. In IRS I and II, more invasive tumors, size >5cm, and positive regional nodes were associated with a worse prognosis in non-metastatic patients. Patients in group I and II with ARMS also had worse outcomes than those with ERMS.29

In IRS III, a poorer prognosis was associated with positive nodes, size >5 cm, distant metastases, both local and distant recurrence, and age >10 years on univariate analysis. With multivariate analysis, positive nodes and distant metastases at presentation were both associated with a significantly worse survival rate. The survival rate for higher clinical groups was worse than that of lower groups. Survival also decreased with increasing disease stage.28

In IRS IV some of the same factors associated with poor prognosis were re-confirmed: higher stage and clinical group; positive regional nodes; larger size; and more invasive tumors on univariate analysis. With multivariate analysis, only stage and group were statistically significant.26

Current recommendations for RMS of the extremities take into account these prognostic factors as well as experience gained during the IRS and similar studies.19,30 In general, complete resection with negative margins seems to have even greater importance for improving survival in patients with extremity RMS compared to other sites.31 If microscopic residual disease is present, primary re-excision should be performed, especially in extremity sites as this is often technically possible and these tumors otherwise carry such a poor prognosis.31 If achieving negative margins with either primary surgery or re-excision would result in major functional or cosmetic loss, however, it is advisable to consider pre-operative chemotherapy and radiation followed by surgery. Results using this treatment system have shown improved outcomes in patients who can be changed from group III to group I.31 Radiation should be used for all patients with extremity RMS and alveolar subtype, no matter which group they are in, except for group I patients with ERMS. Since the rate of lymph node involvement in extremity RMS is so high, lymph node sampling is necessary and newer techniques such as sentinel node biopsy may be applicable. Complete nodal dissection has not improved prognosis in extremity RMS and is not recommended. Future directions for extremity RMS include new chemotherapeutic agents and methods to decrease radiation risks. As part of the COG trials for intermediate-risk NRSTS, irinotecan and earlier administration of radiation are currently being investigated. The utility of positronemission tomography in assessing tumor response to aid in determination of prognosis is also part of that investigation. Targeted therapy, particularly for ARMS but also for RMS in general, is a focus of this research. Decreasing the radiation field is the subject of several recent studies,32,33 and the hope is that late effects can be diminished with these new techniques.

Non-rhabdomyosarcoma Soft-tissue Sarcoma

Pediatric NRSTS are a heterogeneous group that accounts for about 4 % of cancer cases in children and adolescents <20 years of age.1 The most common pediatric subtypes are synovial sarcoma, malignant fibrous hystiocytoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and fibrosarcoma.1 The proportions of these are likely to change over time as the term ‘malignant fibrous histiocytoma’ is used less frequently.

Unlike RMS, the incidence of NRSTS is higher in adolescents than in younger children, and extremity location represents at least 50 %.34–37 Also unlike RMS, nodal metastases are rare except for certain tumor types, such as clear-cell sarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and, less frequently, synovial sarcoma. Patients present with distant metastases in 15 % of cases, primarily the lung.34–37

Another major difference between RMS and NRSTS is the small number of prospective trials.37–40 Most of the information regarding pediatric NRSTS comes from the extrapolation of data from adult studies in subtypes that may also present in older age groups and from larger retrospective series.34–36 From these studies, prognostic factors similar to RMS have been identified and confirmed in NRSTS. This includes the extent of disease, tumor size, and quality of resection. Similar to adult soft-tissue sarcoma, grade is highly important as a prognostic factor. Unlike in adults, however, lower versus upper extremity, superficial versus deep location, and histological subtype have not been shown to affect prognosis for NRSTS in children.41,42 Survival in children is often found to be better than in adults in these studies, even controlling for other important tumor factors. This has led many to believe that there are different biological factors at play in children compared with adults.3,43 While there is no agreed-upon staging system for pediatric NRSTS, many—including the current COG study—have integrated a risk-based system that incorporates many of the prognostic factors known to be significant. In this system, low-risk patients are those with resectable tumors that are either low grade or high grade and <5cm. Five-year overall survival for this group is very good, at about 90 %. Intermediaterisk patients are those with unresectable tumors or with high-grade tumors ≥5cm. Survival is about 50 % at five years. Patients with metastatic disease make up the high-risk group, and survival is about 15 % at five years.44

Current recommendations for patients with non-metastatic RMS include surgery and radiation to achieve local control with negative margins. In most cases this can be achieved with limb salvage surgery. Amputation is rarely required. If negative margins can be obtained surgically, it is debatable whether radiation should also be used. Many teams recommend this for high-grade sarcomas, but it has not been studied in a prospective manner in children. This is one component of the open, prospective COG study for NRSTS. Typically, radiation is not recommended for low-grade tumors.

Radiation can be a powerful tool to achieve long-term local control if margins are positive and to reduce the size of an unresectable tumor (often in concert with chemotherapy), potentially making it resectable. Radiation carries significant risks, however, which are even more pronounced in a young population than in adults. Radiation affects the growth of bones and soft tissues, can cause permanent joint contractures and stiffness, and, most seriously, can induce secondary sarcomas later in life. Thus, the risks associated with radiation in a child must be weighed against the potential functional loss if a purely surgical approach is used.

The use of chemotherapy in children and adolescents with NRSTS, much as in adults, is highly debatable. The agents with the most activity are doxorubicin and ifosfamide, but response rates only approach 35–40 %.38,39 Chemotherapy is currently often considered in patients with high-grade tumors >5cm and unresectable tumors, and as palliation in metastatic disease. The current COG study will prospectively evaluate chemotherapy in intermediate-risk patients.

For children and adolescents with metastatic disease at presentation, metastectomy can offer a rare chance for cure. Most often, however, the prognosis is dismal. The hope is that further phase I and II trials will identify new agents with particular activity in pediatric NRSTS. Conclusion

In summary, pediatric soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremities is a rare disease with variable outcomes depending on type. RMS of the extremities has such a poor prognosis compared RMS overall that much greater effort is needed to effect improvement. Pediatric NRSTS of the extremities is an arena where few prospective data exist, so continued focused efforts with this particular age group are needed.