Each year, there are an estimated one million newly diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) worldwide. Approximately half of all patients with CRC will develop metastases, and the majority of these patients will die from the cancer. Without treatment, the median survival for patients with metastatic CRC is five to six months. However, the last decade has seen dramatic changes in the management of patients with CRC, due in part to the increasing number of therapeutic options. First-line chemotherapy treatment has evolved from fluorouracil (FU) monotherapy to include folinic acid, and it is now recommended to integrate the use of the cytotoxic agents irinotecan and oxaliplatin. Indeed, combination chemotherapy of fluorouracil and folinic acid with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or irinotecan (FOLFIRI) is associated with greater survival benefits and improved quality of life in patients with advanced CRC. The availability of these combination therapies has seen improved response rates and increased time to progression (TTP) or progression-free survival (PFS) compared with FU and folinic acid alone, with median survival times increasing from approximately 12 months to over 20 months.1–5

Recently, targeted therapies have been introduced and are one of many areas in the advancement of cancer management, representing an attempt to exploit our growing knowledge of the growth, division and survival of normal and malignant cells. Two new targets in metastatic CRC are the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), targeted by bevacizumab (Avastin, Roche), and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), targeted by cetuximab (Erbitux, Merck MSD) and panitumumab (Vectibix, Amgen). Through these new biologic agents, the available options in the therapeutic armamentarium for metastatic CRC have been increased. This short article will focus on the current evidence for agents targeting EGFR.

Targeting the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

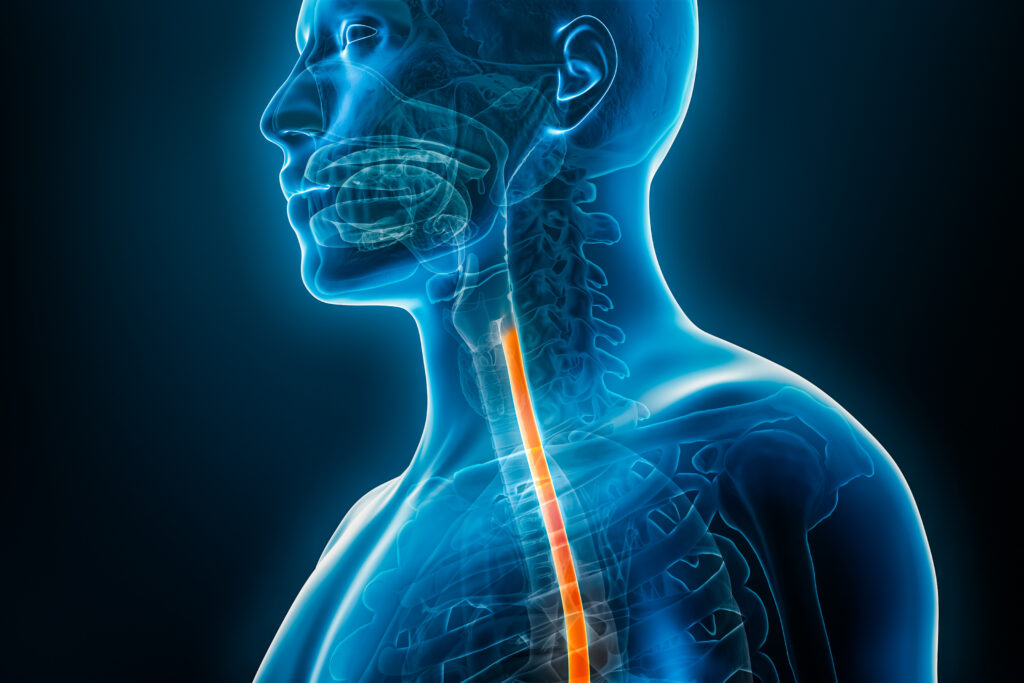

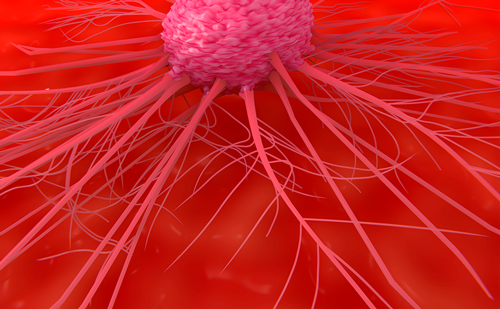

EGFR is one of the most studied molecular targets in anticancer therapy. The EGFR controls a set of signal transduction pathways and intracellular signalling cascades. Deregulation of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity is found in many human cancers, including head and neck, ovarian, oesophageal and breast cancer, as well as CRC.6 The overexpression of EGFR is associated with tumour growth and metastases through cell proliferation, neo-angiogenesis and protection against apoptosis.7 Inhibition of the EGFR pathway has an antitumour effect and can arrest the cell cycle, induce cell apoptosis and prevent angiogenesis, metastasis and further tumour cell invasion.

The anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab have both shown efficacy and activity in chemotherapy-refractory patients with advanced CRC. However, the majority of studies pertaining to the anti-EGFR antibodies have focused on cetuximab, and the available data on panitumumab are much more limited.

Cetuximab

Cetuximab is an immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) human–mouse chimaeric monoclonal antibody that binds specifically to EGFR to inhibit receptor signalling. Pre-clinical trials demonstrated that cetuximab was able to reduce EGFR-dependent tumour cell proliferation and inhibit angiogenesis and, when combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy, increased antitumour activity.

The BOND trial found greater response and delayed TTP with combination therapy of cetuximab and irinotecan compared with cetuximab monotherapy in EGFR-positive irinotecan-refractory metastatic patients.8 In this trial, 329 patients refractory to irinotecan-based therapy were randomly assigned to receive either cetuximab plus irinotecan or cetuximab monotherapy. The study found that the rate of response in the combination therapy group was significantly higher than that in the monotherapy group (23 versus 11%; p=0.007). Furthermore, the median TTP was significantly greater in the combination therapy group (4.1 versus 1.5 months; p<0.001). It should be noted that cross-over to the cetuximab plus irinotecan arm was allowed after progression on cetuximab monotherapy, thus the BOND data were not powered to provide information on any potential survival benefits conferred by cetuximab. The BOND data supported results from previous trials,9,10 and were pivotal in confirming the benefits of cetuximab in CRC, ultimately leading to the approval of cetuximab for the treatment of irinotecan-refractory patients with EGFR-expressing advanced CRC by both the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA).

Second- and Third-line Therapy Trials with Cetuximab

The role of cetuximab in second-line therapy was initially demonstrated in chemotherapy-refractory tumours in phase II studies.8,10,11 The results of the combination arm in the BOND study were confirmed by data from the MABEL trial, which involved 1,147 irinotecan-refractory patients with advanced CRC. The addition of cetuximab to four different irinotecan regimens resulted in overall PFS rates of 61% at 12 weeks and 34% at 24 weeks. Median overall survival (OS) was reported to be 9.2 months.12

The question of whether cetuximab confers survival advantage in advanced CRC was investigated in a large phase III randomised controlled trial involving 572 patients with EGFR-positive irinotecan- and oxaliplatinrefractory disease. Compared with best supportive care (BSC) alone, the addition of cetuximab at the standard loading dose of 400mg/m2 followed by weekly one-hour 250mg/m2 to BSC significantly improved OS and PFS. Median OS in the cetuximab group was 6.1 months, versus 4.6 months in the group assigned to BSC alone.13

In the EPIC phase III study, 1,298 patients with oxaliplatin-refractory EGFRexpressing tumours were randomised to receive irinotecan with or without cetuximab. Patients in the cetuximab arm experienced significantly improved PFS, response rates and disease control, although there was no survival benefit.14 Such success in second-line treatment has led to investigations into the efficacy of cetuximab as a potential first-line therapy.

First-line Therapy Trials with Cetuximab

Several preliminary phase II studies have shown encouraging results for cetuximab in combination with various chemotherapy regimens in the first-line setting.15–18

The CRYSTAL study was a large-scale phase III investigation into the effectiveness of cetuximab in combination with FOLFIRI versus FOLFIRI alone in a first-line setting, treating 1,217 patients with EGFRexpressing metastatic CRC. The patients who received the cetuximab combination therapy had significantly longer PFS and increased response and resection rates than those receiving FOLFIRI alone.

Furthermore, a higher resection rate of metastases in patients with previously unresectable metastases was reported.19,20 Although cetuximab is currently approved only as second- or third-line treatmentfor metastatic CRC, data from the CRYSTAL trial suggest that cetuximab is a strong candidate to be considered for first-line therapy.

Another large phase III study is the three-armed COIN trial, which is currently under way with plans to treat 2,421 patients with metastatic CRC regardless of EGFR-expression status. Patients will be randomised to receive continuous FOLFOX, continuous FOLFOX in combination with cetuximab or FOLFOX with a drug holiday after 12-week treatment intervals, restarting only if progression is observed; results have yet to be reported.

Panitumumab

Panitumumab is the first fully humanised monoclonal antibody targeting the EGFR. This IgG2 antibody recently received EMEA approval for use as monotherapy in patients with EGFR-expressing metastatic CRC who have failed prior classic chemotherapy and whose tumours contain non-mutated (wild-type) KRAS. Panitumumab is FDA-approved as monotherapy for the treatment of patients with EGFR-expressing metastatic CRC who experienced disease progression while receiving or following chemotherapy regimens containing fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin or irinotecan. Supporting data for the approval of panitumumab was based on observations that the addition of panitumumab to BSC led to significant increases in mean PFS in comparison with BSC alone.21 In the study, 463 EGFR-positive oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-refractory patients were randomly assigned to panitumumab 6mg/kg every two weeks plus BSC or BSC alone.

Panitumumab significantly prolonged median PFS (eight versus 7.3 weeks; p<0.0001). However, no difference was observed in OS, because BSC-treated patients were allowed to receive panitumumab after progression. A recent sub-analysis of the study revealed that the efficacy of panitumumab monotherapy was confined to patients with wild-type KRAS tumours. Median PFS in the wild-type KRAS group was 12.3 weeks for panitumumab compared with 7.3 weeks for BSC (p<0.0001), and response rates to panitumumab were 17 and 0% for the wild-type and mutant groups, respectively.22

Antibody Combinations

Dual biologics in combination with oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based chemotherapy are not currently used in clinical practice. There are several trials under way that are investigating the potency and synergistic effect of monoclonal antibodies used in combination. In the BOND-2 trial, irinotecan-refractive bevacizumab-naïve patients were treated with bevacizumab and cetuximab with or without irinotecan. Patients receiving the additional irinotecan therapy were more likely to achieve partial responses and improvements in median TTP. Furthermore, a comparison with the data from the previous BOND study suggests that the addition of bevacizumab to the cetuximab–irinotecan combination increases treatment efficacy without producing any unexpected toxicities.23 Given the promising tolerability and activity of these results, further investigation is needed into this combination regimen for first-line therapy. The BOND-3 trial will continue to test antibody combinations, administering bevacizumab and cetuximab with or without irinotecan to bevacizumab-refractory patients.

Interestingly enough, the PACCE phase III trial showed completely contrasting results. A preliminary review of interim data revealed that the addition of panitumumab to bevacizumab and FOLFOX inexplicably increased toxicity without improving efficacy, leading to significantly worse PFS and survival than FOLFOX and bevacizumab alone.24 This led to the discontinuation of the trial.

Toxicity and Adverse Effects

Because cetuximab and panitumumab are often combined with chemotherapy in the clinical setting, the observed side effects are similar to those seen in classic chemotherapy. However, it has been reported that the addition of antibodies to chemotherapy can slightly increase the incidence of diarrhoea.

The anti-EGFR antibodies themselves cause over 80% of patients to develop an acneiform-like rash.8,21 Cetuximab has also been associated with the development of allergic reactions, which are less likely with the humanised antibody panitumumab than with the chimaeric cetuximab. This is rare, however, with the overall reported incidences with cetuximab ranging from 1.2 to 3.5%.8,10 The antibodies are also associated with hypomagnesaemia due to renal loss of magnesium in up to 97% of patients.25

Factors Predictive of Response to and Efficacy of Anti-epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Antibody Treatment

Immunohistochemistry

The presence of EGFR in tumours is often detected by immunohistochemistry tests, and approximately 77% of patients with CRC have an overexpression of EGFR.26 However, no studies have been able to find a connection between the EGFR level of expression as determined by immunohistochemistry and the treatment efficacy of the anti-EGFR antibodies. In fact, whether a patient has a high or low EGFR-expression rate, or no expression at all, is irrelevant; these patients all have similar chances of benefiting from anti-EGFR antibody treatment.11 The immunohistochemistry determination of EGFR levels is therefore a poor indicator of which tumours would be most sensitive to targeted therapy with anti- EGFR antibodies.

There are many ongoing studies investigating the role of cetuximab in EGFR-positive and EGFR-negative CRC as determined by immunohistochemistry. To date, the FDA and EMEA have approved cetuximab only in EGFR-positive CRC patients, but this may very well change if results from these clinical studies support the use of cetuximab in EGFR-negative tumours.

Rash

The high incidence of rash in patients treated with anti-EGFR antibodies is actually good news for patients, as retrospective analyses have shown a direct correlation between rash and activity: the greater the skin reaction, the higher the response rate and the longer the median TTP, PFS and OS.8,21 In the EVEREST study, CRC patients failing prior irinotecancontaining therapy were treated with progressively escalating doses ofm cetuximab until a rash or response was induced in order to investigate the relationship with skin reaction. Not only did the patients receiving the scaled dosages have significantly higher skin toxicity, they also had a higher response rate.27 However, although there is a correlation between skin reaction and response to the drug, this alone is not a strong enough predictive factor of efficacy and should be applied with caution.

KRAS

The KRAS gene, a main effector downstream of the EGFR receptor in the signalling pathway, is able to predict when there will be a lack of response from the anti-EGFR antibodies. It was recently found that cetuximab and panitumumab are inactive in patients who have mutations in the KRAS gene, and that only patients with the wild-type KRAS will benefit from these drugs.22,28,29 Under panitumumab monotherapy, patients with wildtype tumours were most likely to have an increased PFS.22 However, the KRAS status is not a strong enough predictive factor because it is still not able to definitively identify specifically which patients will respond to drug treatment. Although wild-type status indicates that a patient is likely to respond, only a subgroup of these patients will reap the largest survival benefit; this was demonstrated in a recent study in which only 27 of 66 KRAS wild-type patients responded to cetuximab.29

Future Research Considerations

The new biologic agents bevacizumab, cetuximab and panitumumab are being increasingly integrated into clinical practice and treatment of CRC. The anti-EGFR antibodies have demonstrated ability in increasing the chances of prolonged survival in patients with metastatic CRC, but many questions remain. First, it is still not known how the use of cetuximab can be optimised when considering classic chemotherapy, but results from ongoing studies such as COIN, BOND-2 and BOND-3 should help resolve this problem. Furthermore, the toxicity observed in the PACCE trial still needs to be addressed. Perhaps the variance is partly attributed to the underlying variation in their properties, i.e. that cetuximab is an IgG1 and panitumumab an IgG2 antibody; further studies are necessary to evaluate differences between their respective activity and toxicity profiles. It is also still undetermined how to effectively predict patient response to anti-EGFR biologics. Immunohistochemistry and the corresponding EGFR levels have not been found to correlate to treatment response. The degree of skin reactions has been associated with the extent to which a patient will respond to antibody treatment, but is not guaranteed; therefore, skin rash should not be used as a surrogate for the clinical efficacy of anti-EGFR antibodies, but rather remains a marker that requires further investigation. KRAS status has predictive value, but this is not absolute, as only a proportion of tumours with wild-type KRAS respond to the antibodies. Further studies are necessary to determine whether there are other molecular markers that may have any predictive value for drug response.

Ultimately, the goals are both strategic and patient-orientated. The best method of implementing these anti-EGFR antibodies must be determined to find out which antibodies should be combined with chemotherapy in the first-line setting. More crucial is the fact that it is still not possible to accurately predict with complete confidence which patients will show the best drug response, which patients will benefit and which will not. ■

My Learning

Login

Sign Up FREE

Register Register

Login

Trending Topic

12 mins

Trending Topic

Developed by Touch

Mark CompleteCompleted

BookmarkBookmarked

Allan A Lima Pereira, Gabriel Lenz, Tiago Biachi de Castria

NEW

Despite being considered a rare type of malignancy, constituting only 3% of all gastrointestinal cancers, the incidence of biliary tract cancers (BTCs) has been increasing worldwide in recent years, with about 20,000 new cases annually only in the USA.1–3 These cancers arise from the biliary epithelium of the small ducts in the periphery of the liver […]

touchREVIEWS in Oncology & Haematology. 2025;21(1):Online ahead of journal publication