Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a malignant soft tissue tumor, which represents about 10% of all soft tissue sarcomas.1 It occurs most often in the lower extremities of young men, and is very rare in the head and neck region, with an incidence of about 2–4%.2,3 The origin of the SS remains uncertain, although it is believed that its origin would be in undifferentiated stem cells and tissue that are related neither to ultrastructural, nor to histological synovial tissue, being only <5% intraarticular. 4 Typically, it affects patients between 14 and 35 years of age, and its clinical presentation includes the presence of a neck mass, hoarseness, dysphagia, and dyspnea.5 When it is presented in the head and neck (HN) it seems to have better prognosis than in the extremities, with five-year survival for head and neck between 47% and 82%.6 The first report in HN was in 1954,7 and the most frequent location has been in hypopharynx and lymph nodes. Other locations are reported in parotid gland, paranasal sinuses, larynx, pharynx, and the retropharyngeal space.2,8 There are only few reports of SS in infratemporal fossa.4,9–13 The optimal treatment has not been established, but complete resection with or without radiotherapy and chemotherapy is currently considered the best available therapy. Here is a case of synovial sarcoma located in the left infratemporal fossa. We describe its diagnosis, therapeutic confrontation, and evolution.

Case report

A 32-year-old man showed at the dental office in March 2014, due to pain in his left mandibular temporomandibular joint with about 3 months of evolution. Bruxism was diagnosed and a plane relaxation for 3 months was prescribed; however, the patient did not experience a good response.

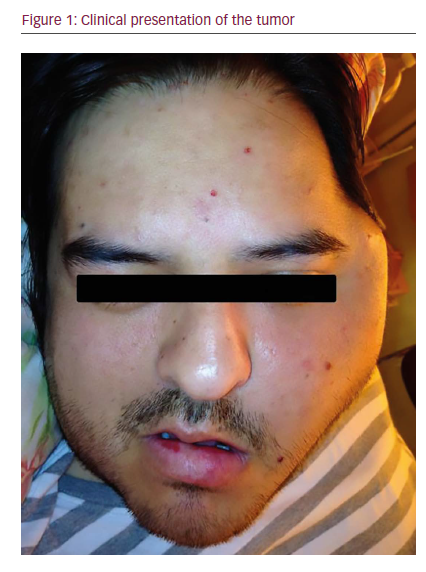

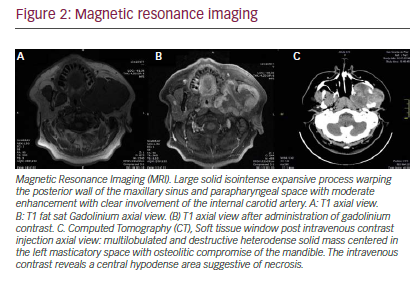

In June 2014 he was referred to a maxillofacial surgeon who confirmed a volume increase in the left zygomatic region (see Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, revealing a multilobulated large, aggresive, expansive, and destructive heterodense solid mass centered in the left masticatory space. The lesion also involved the oval foramen, ipsilateral infratemporal, and pterygopalatine fossa. There was osteolitic compromise of the mandible, temporomandibular join, pterygoid process, middle cranial base, and sphenoid wing. At its largest diameter, the lesion measured 8 cm and enhancement was seen following intravenous contrast administration with central hypodense areas suggestive of necrosis. Lymphadenopathy was observed with hypodense center in the II ganglionar level as large as 10 mm were present (see Figure 2C). Subsequently, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study was performed revealing in T1 sequence a solid isointense expansive process warping the posterior wall of the maxillary sinuse and

parapharyngeal space (see Figure 2A). An additional MRI T1 sequence following administration of gadolinium contrast material showed moderate enhancement with clear involvement of internal carotid artery (see Figure 2B).

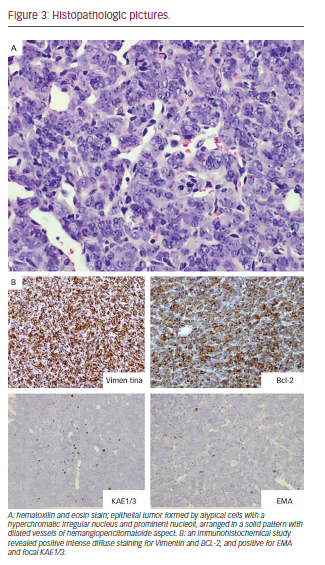

In this context, it was decided to perform incisional biopsy of the lesion; the histological analysis was reported as SS (see Figure 3). The study for metastasis was negative. Based on the size of the tumor, the Head and Neck Tumor Board (HNTB) recommended intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in order to reduce its volume and try posterior surgical resection.

After IMRT, with total dose of 70 Gy, a reduction in tumor mass is achieved; however, this is not enough to raise the total security resection margins, 6 months after treatment was completed, a follow-up computed tomography (CT) exam showed presence of lung nodules suggestive of metastasis. Following additional review by the HNTB, palliative chemotherapy was recommended. He received five cycles of Doxorubicin and ifosfamide with mesna, showing good tolerance, pain decrease and stabilization of pulmonary nodules. Upon finishing this article, 2 years after diagnosis, the patient remains in palliative care, with local complications and deterioration of his performance status.

Discussion

An epithelial form with columnar cells and other non-epithelial cells with fusiform are observed: SS in two different histological forms. The most common SS showing two types of shapes is known as biphasic. Tumors with only epithelial components are rare, and are called monophasic. Differentiation of the latter type with other types of neoplasias is difficult.14 The variety of our case corresponded to a monophasic SS; we performed the diagnosis through intense diffuse positive staining to vimentin and Bcl-2, and the positive focal dialing EMA and KAE1/3, which is typical of these tumors.

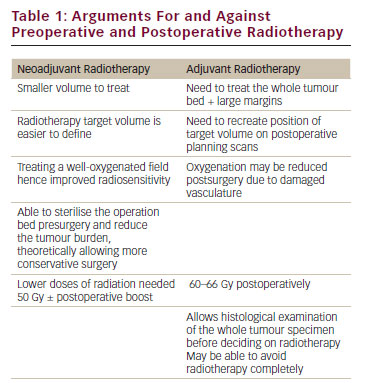

The current treatment of the SS is based on surgical resection with safety margins, with or without chemoradiotherapy. In HN, complete resection with adequate margins is difficult, and impossible in many cases, given the complex anatomy; however, it generates better results in terms of recurrence and survival. Regarding chemoradiotherapy, several strategies have been reported, with different results.

Some studies reported that postoperative dose radiotherapy of 50–65 Gy in patients with clear safety margins or microscopic residual tumor was effective in reducing local recurrence, but not survival,15–17 nor the chemotherapy before or after surgery in two different research works.17,18 Therefore, surgical resection with safe margins is most important; chemoradiotherapy effectiveness remains uncertain. Distant metastases occur in up to 50–70% of cases, and are frequent in cervical lymph nodes by 10–20%. Overall, it is a poor prognosis, with a fiveyear survival rate of 25–62% and 10–30% for 10 years.1 Predictors of worse prognosis for SS have been proposed, such as diameter >5cm, biphasic type, primary site based skull, bone involvement, and positive margins after surgical resection.8,15

The causes of death in SS are recurrences and distant metastases (lungs after cervical lymph nodes). Although local control is difficult, it has been improved with the development of new surgical techniques. In our patient, IMRT treatment was decided due to the size of the tumor, and virtually no possibility of surgical resection with negative margins.

According to our knowledge it is the first reported case in South America. We present the limits of treatment of an infratemporal fossa SS. A more effective therapeutic confrontation is required, especially for tumors that cannot be completely resected.

Conclusions

According to our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an infratemporal fossa SS in South America. We present the limits of treatment of an infratemporal fossa SS. A more effective therapeutic confrontation is required, especially for tumors that cannot be completely resected.