Urothelial carcinoma is the most common histologic type of bladder cancer in the USA and Europe, accounting for 90% of all bladder cancers. It is the sixth most common type of cancer diagnosed in the USA, and the 10th leading cause of cancer death, with an estimated 17,980 deaths predicted in 2020.1 Although the 5-year survival for all cases of urothelial carcinoma is approximately 77%, it is only 5.5% for patients with distant metastatic disease.1

Since the early 1990s, the standard first-line treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma has been multiagent cisplatin-based chemotherapy.2 Given that the median age of diagnosis is 73,1 a large number of patients are not eligible for treatment with cisplatin due to poor performance status, renal dysfunction, or other comorbid conditions.3 In patients ineligible for cisplatin-based chemotherapy, carboplatin-based regimens have been used, but with limited effectiveness.4 Despite initial response rates of approximately 50–60%,5,6 the median overall survival (OS) with platinum-based chemotherapy in the pre-immunotherapy era was only 14–15 months.7

Given the limitations of platinum-based regimens, there has been a need for new therapeutic options for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibody–drug conjugates, and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-targeted therapies have revolutionized the treatment paradigms and improved outcomes for patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma. We review: the currently approved agents for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma in patients who are refractory to, or ineligible for, platinum-based chemotherapy; the role of maintenance immunotherapy post-platinum chemotherapy; ongoing trials of immunotherapy plus chemotherapy in the first-line setting; and FGFR-targeted therapies.

Immunotherapy in second-line setting for metastatic urothelial carcinoma

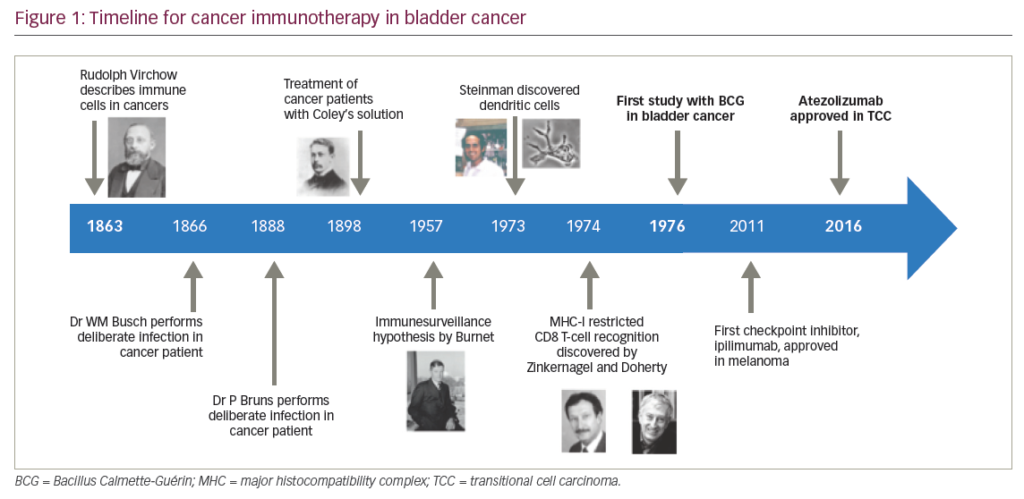

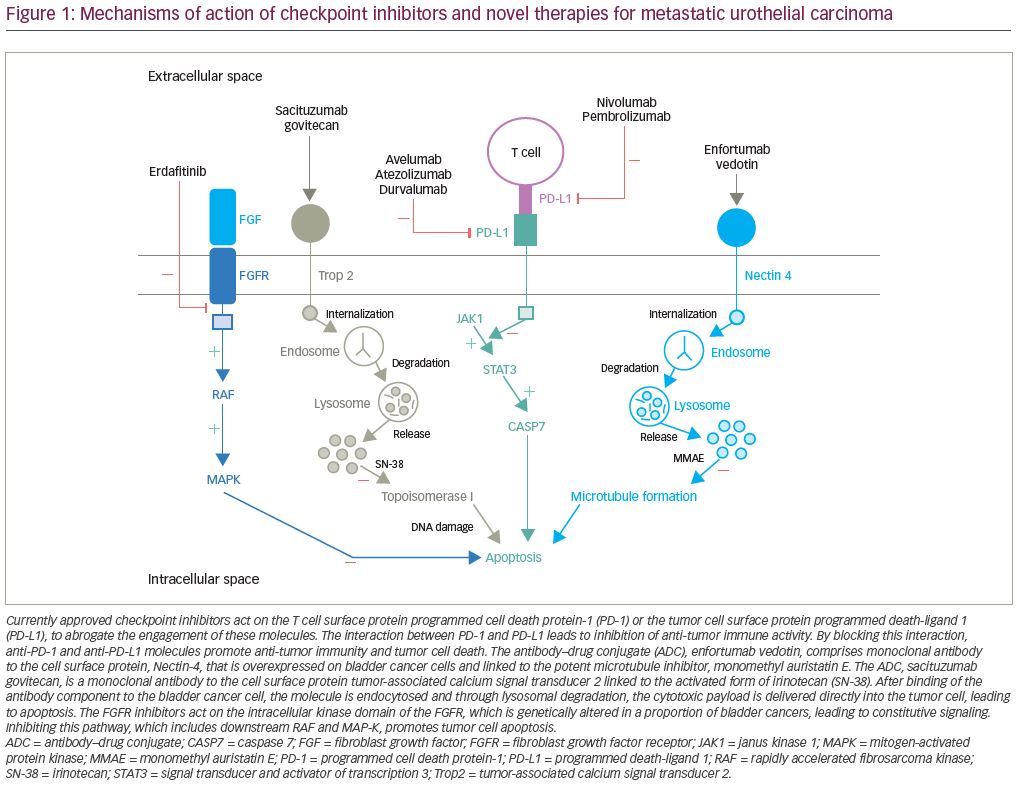

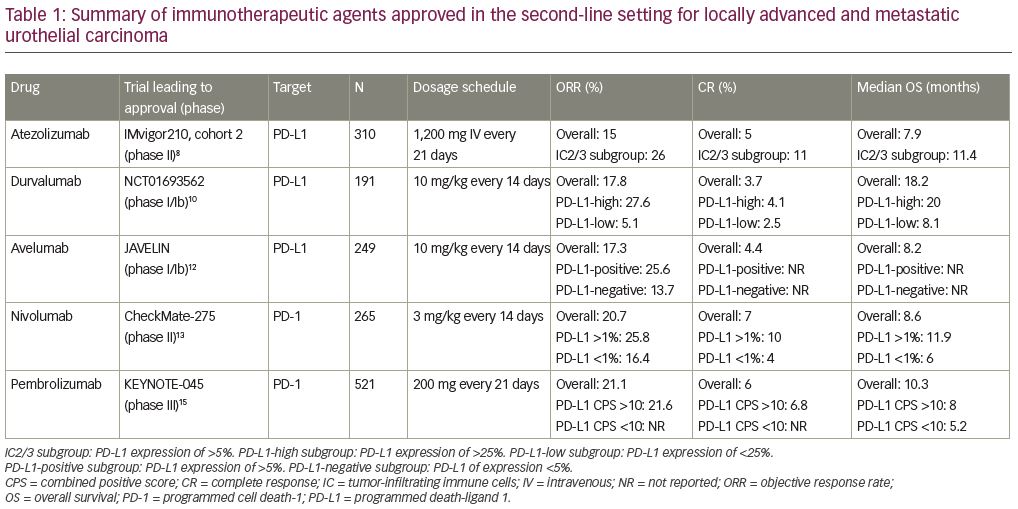

Immune checkpoint inhibitors were first investigated in urothelial carcinoma in the second-line setting for patients with platinum-refractory disease (Figure 1). There are currently five US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved immunotherapeutic agents available for the treatment of patients who have disease progression after treatment within platinum-containing chemotherapy; these are atezolizumab, durvalumab, avelumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab (Table 1).

Atezolizumab

Atezolizumab is an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) therapy that was granted accelerated FDA approval in May 2016 for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, post-platinum-containing therapy, based on results from IMvigor210. IMvigor210 was a multicohort, single-arm, phase II study of atezolizumab in advanced urothelial carcinoma.8 Cohort 2 of this trial enrolled patients with platinum-refractory urothelial carcinoma. Patients treated with atezolizumab (1,200 mg intravenous [IV] on day 1 of a 21-day cycle) had an objective response rate (ORR) of 15%. Results were stratified by degree of PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating immune cells (ICs) or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) using the Ventana SP142 assay. The IC2/3 subgroup—those with PD-L1 expression ≥5%—had a higher ORR of 26%, with 11% achieving a complete response (CR). For the entire population, OS was 7.9 months, while the IC2/3 subgroup had an OS of 11.4 months.

The results of IMvigor210 led to a phase III study, IMvigor211, comparing atezolizumab to physician’s choice chemotherapy for platinum-refractory urothelial carcinoma.9 Among the 931 patients enrolled in this trial, 25% were IC2/3. Of that PD-L1-high subgroup, the median OS was 11.1 months with atezolizumab monotherapy versus 10.6 months for chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.87; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.63–1.21; p=0.41), with 7% achieving a CR. The hierarchical primary endpoint definition precluded further formal statistical analysis for other subgroups. Despite the lack of OS benefit, treatment with atezolizumab was found to be well tolerated and produced more durable responses compared with chemotherapy.

Durvalumab

Durvalumab is another anti-PD-L1 therapy that received accelerated FDA approval in the second-line setting for platinum-refractory patients in May 2017. The approval was based on the results of a phase I/II study of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma who were treated with durvalumab at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for up to 12 months.10 In this trial, PD-L1 expression of ≥25% in either TILs or tumor cells was considered to be a high level of expression. The ORR was 17.8% for the entire study population with a CR rate of 3.7%. Notably, ORR was 27.6% in the PD-L1-high subgroup and 5.1% in the PD-L1-low or -negative subgroup. For the overall study population, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 1.5 months and OS was 18.2 months.

Avelumab

Avelumab is an anti-PD-L1 antibody that also received accelerated FDA approval in May 2017 in the second-line setting post-platinum therapy. The results of the phase Ib JAVELIN study of metastatic urothelial carcinoma in patients who had progression of disease after platinum-based chemotherapy, or who were ineligible for treatment with cisplatin, led to this approval.11 After 6 months of follow up, an updated analysis showed an ORR of 17.3% in the entire study population with a CR rate of 4.4%.12 When analyzed by level of PD-L1 expression, the ORR was 25.6% for the

PD-L1-positive (defined as ≥5% PD-L1 expression) subgroup and 13.7% in the PD-L1-negative (defined as <5% PD-L1 expression) subgroup.

Nivolumab

Nivolumab is an anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) therapy that also received FDA approval in the second-line platinum-refractory setting. This approval was based on the results of the phase II CheckMate 275 trial which evaluated nivolumab monotherapy in patients with metastatic or locally advanced platinum-refractory urothelial carcinoma.13 At the 2019 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, updated results of CheckMate 275 with a minimum follow up of 33.7 months were presented. The ORR was 20.7% and CR was 7% with a median OS of 8.6 months and a median duration of response of 20.3 months.14 This trial evaluated its endpoints in all treated patients and by tumor PD-L1 expression. Efficacy was observed in all patients, regardless of PD-L1 expression.

Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab is an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody that was FDA approved in the second-line setting in May 2017. This approval was granted based on the phase III KEYNOTE-045 study of patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma that either recurred or progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to be treated with either pembrolizumab or chemotherapy.15 The ORR was 21.1% with a 6% CR rate. The median PFS was longer for the chemotherapy arm at 3.3 months versus 2.1 months in the pembrolizumab arm. However, median OS was significantly improved in the pembrolizumab arm at 10.3 months versus 7.4 months in the chemotherapy arm. PD-L1 expression status was assessed using the 22C3 pharmDx assay (Carpinteria, CA: Dako, Agilent Pathology Solutions), which tests PD-L1 expression of both tumor cells and TILs. PD-L1 expression status was defined by the combined positive score (CPS), which is the percentage of PD-L1-expressing tumor cells and TILs relative to the total number of tumor cells. When outcomes were evaluated based on PD-L1 expression status, the median OS was higher with pembrolizumab for patients with PD-L1 CPS scores ≥10 (8.0 versus 5.2 months; p=0.005).

Comparing immunotherapeutic agents

After treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy, we now have several available treatment options, which leads to the question of which of these drugs to use. There are currently no trials directly comparing the efficacy or safety of these medications to help guide our treatment decisions. At present, pembrolizumab is the only agent to demonstrate an OS benefit in a randomized controlled phase III trial.15 Although IMvigor211, the phase III study of atezolizumab, did not demonstrate a statistically significant OS benefit, this could be a result of trial design rather than drug activity.9 Durvalumab, avelumab, and nivolumab have similar efficacy, but lower levels of evidence when compared with pembrolizumab. Despite the lack of a head-to-head comparison of toxicity, the rates of immune-related adverse events are similar between PD-1 and PD-L1 agents. A recent meta-analysis evaluated the safety profiles of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 agents and found that they were comparable for both immune-related adverse events and any adverse events.16 There were also similar rates of adverse events leading to death or discontinuation of therapy when comparing anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies. The choice of drug to use will also depend on a multitude of other factors, including PD-L1 expression, cost, and dosing schedule. Pembrolizumab was recently approved by the FDA for dosing every 6 weeks, rather than every 3 weeks, providing a more convenient dosing schedule for many patients.17

Immunotherapy in the first-line setting for metastatic urothelial carcinoma

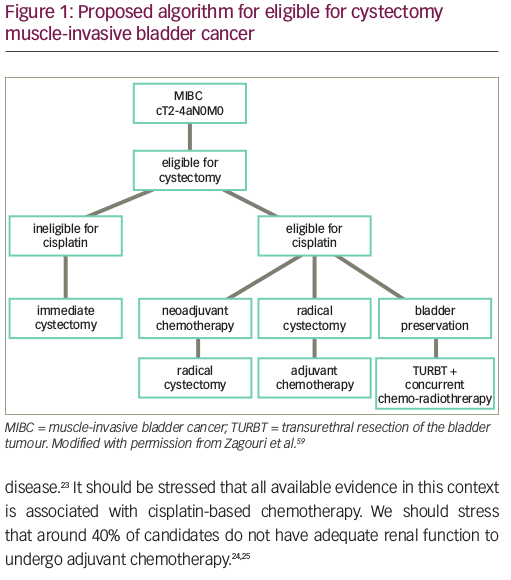

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains the standard of care, first-line systemic therapy for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. However, for patients with a poor performance status or with comorbid conditions, such as impaired renal function, hearing loss, or neuropathy, cisplatin-based therapy is not well-tolerated or is contraindicated.3 It is estimated that 30–50% of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma are ineligible for cisplatin-based therapy.18 In the population of patients that are ineligible for treatment with cisplatin, carboplatin-based regimens have been the standard of care. These carboplatin-based regimens have a reported 36.1% ORR, 3.4% CR, and an OS of approximately 9 months, considerably lower than those treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy.4 In this context, several studies have evaluated the role of first-line checkpoint inhibition.

Pembrolizumab monotherapy

The single-arm, phase II KEYNOTE-052 study enrolled cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced urothelial cancer who had not been previously treated with systemic chemotherapy, and treated them with pembrolizumab.19 Based on the results of this study, pembrolizumab was given an accelerated approval for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma in cisplatin-ineligible patients. The results of the long-term follow-up analysis, KEYNOTE-052, were presented at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting and demonstrated that among the 370 patients assessed, the ORR was 28.9% and CR was 8.1% at a median follow up of 11.5 months.20 The ORR was 47.3% in patients with a PD-L1 expression CPS of ≥10. Median OS was 11.5 months for the entire study population and higher among the subgroup of PD-L1-positive (CPS ≥10) patients, at 18.5 months.

Atezolizumab monotherapy

Accelerated approval of atezolizumab for the first-line treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma in cisplatin-ineligible patients was granted based on the results from cohort I of the phase II IMvigor210 trial.21 This trial enrolled previously untreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who were cisplatin-ineligible, and 119 patients were treated with atezolizumab. The ORR in all patients was 23% with a CR rate of 9% at a median follow up of 17.2 months. The Ventana SP142 assay was used to measure PD-L1 expression by staining ICs.

For the IC2/3 subgroup (those with PD-L1 expression ≥5%), ORR was 28%. The median OS was 15.9 months for the entire study population. Although not a statistically significant difference, the median OS was 12.3 months for the IC2/3 subgroup, and 19.1 months in the IC0/1 subgroup (those with PD-L1 expression <5%).

PD-L1 expression and first-line immunotherapy

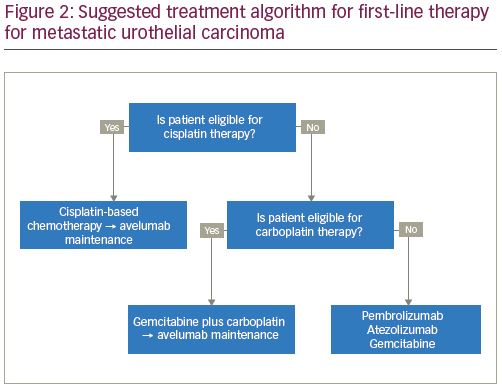

Based on interim safety analyses from KEYNOTE-361 and IMvigor130, the FDA issued a safety alert for pembrolizumab and atezolizumab that reported decreased survival with immunotherapy compared with chemotherapy among subgroups with low PD-L1 expression. Low PD-L1 expression is defined as a CPS of <10 using the 22C3 pharmDx Assay for treatment with pembrolizumab, and as an IC of <5% as measured by the Ventana SP142 assay (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for treatment with atezolizumab. Subsequently, the approvals for pembrolizumab and atezolizumab in the first-line cisplatin-ineligible setting were updated to exclude patients with low PD-L1 expression, unless they are ineligible to receive carboplatin secondary to comorbidities or poor performance status. The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Bladder Cancer guidelines reflect these findings.22 Thus, for those who are cisplatin-ineligible and have low PD-L1 expression, carboplatin-based chemotherapy remains the standard of care, and for those with high PD-L1 expression, checkpoint inhibitors should be considered (Figure 2).

Immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy

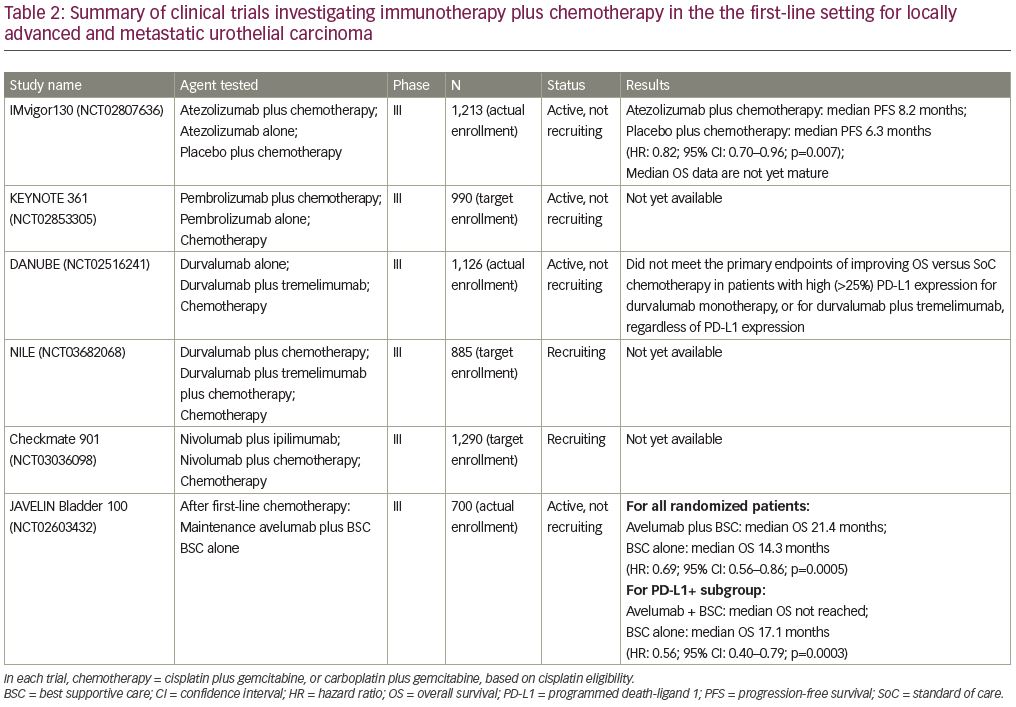

Multiple trials investigating combination chemotherapy and immunotherapy have been initiated since the approvals of first-line, single-agent atezolizumab and pembrolizumab in advanced urothelial carcinoma. Here we discuss several ongoing phase III clinical trials investigating this combined therapy approach in the first-line setting (Table 2).

IMvigor130 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02807636) enrolled 1,213 patients eligible for platinum-based chemotherapy with metastatic urothelial carcinoma, and randomized them to one of three arms.23 Arm A received atezolizumab plus chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus cisplatin or carboplatin), arm B received atezolizumab alone, and arm C received placebo plus chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus carboplatin or cisplatin). Co-primary endpoints of this study were PFS and OS for the atezolizumab plus chemotherapy arm versus the placebo plus chemotherapy arm, and OS for the atezolizumab alone arm versus the placebo plus chemotherapy arm. The addition of atezolizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy resulted in an improved median PFS when compared with the placebo plus chemotherapy arm (8.2 months versus 6.3 months; HR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.70–0.96; p=0.007). Of note, the combination of atezolizumab plus chemotherapy did not lead to higher rates of treatment discontinuation when compared with platinum-based chemotherapy alone, with adverse events leading to treatment withdrawal in 34% of patients in both arms A and C.

The median OS data are not yet mature, but interim analysis of OS showed a trend toward improvement with combination atezolizumab plus chemotherapy, although it was not statistically significant. The atezolizumab alone arm did not show a statistically significant OS benefit compared with the placebo plus chemotherapy arm.23 These early data also show decreased survival with atezolizumab alone compared with the placebo plus chemotherapy arm. However, this seems to be limited to the low PD-L1 expression subgroups. These observations contributed to the FDA’s decision to restrict the use of atezolizumab to PD-L1-positive patients, unless they are also ineligible for carboplatin-based therapy, as noted above.17,24

KEYNOTE-361 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02853305) is a randomized, open-label, phase III trial comparing pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in previously untreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.25 Patients are assigned randomly 1:1:1 to receive pembrolizumab alone, pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, or chemotherapy alone. KEYNOTE-361 has completed enrollment and is in its follow-up stages.

DANUBE (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02516241) is a randomized, open-label, phase III trial of durvalumab with or without tremelimumab versus standard of care chemotherapy in treatment-naive patients with unresectable and/or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.26 As per a press release from AstraZeneca (on March 6, 2020), DANUBE did not meet the primary endpoints of improving OS versus standard of care chemotherapy for durvalumab monotherapy in patients with high (≥25%) PD-L1 expression or for durvalumab plus tremelimumab in patients regardless of PD-L1 expression. However, these agents are being further investigated in the NILE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03682068), which is a randomized, open-label, phase III trial comparing durvalumab plus standard of care chemotherapy versus durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus standard of care chemotherapy versus standard of care chemotherapy alone, in previously untreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.27 Durvalumab is an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody and tremelimumab is an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) monoclonal antibody. By targeting two different immune checkpoints, this study will help to assess whether there are additive or synergistic effects in combination with chemotherapy compared with a single immune checkpoint inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy.

Checkmate-901 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03036098) is a randomized, open-label, phase III trial evaluating nivolumab plus ipilimumab, and nivolumab plus standard of care chemotherapy versus standard of care chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.28 Both cisplatin-eligible and cisplatin-ineligible patients will be randomized to receive either combination immunotherapy or platinum-based chemotherapy. Additional cisplatin-eligible patients will be randomized to receive either nivolumab plus chemotherapy or cisplatin-based chemotherapy alone. We await data from this and the other combination chemotherapy and immunotherapy trials above, the results of which could guide treatment in the first-line setting in the years to come.

JAVELIN Bladder 100 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02603432) is a randomized, phase III trial evaluating first-line maintenance with avelumab after treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.29 Patients who did not progress on first-line chemotherapy were randomized to either receive avelumab versus best supportive care (BSC) alone after completion of platinum-containing first-line chemotherapy. The results at the time of the first interim analysis were presented at ASCO 2020 and showed that avelumab plus BSC significantly prolonged OS when compared with BSC alone. In all randomized patients, the median OS was 21.4 months in the avelumab plus BSC group and 14.3 months with BSC alone (HR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.56–0.86; p=0.0005). The PD-L1-positive subgroup also demonstrated significantly improved OS versus BSC alone, with median OS not reached in the avelumab plus BSC arm versus 17.1 months with BSC alone (HR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.40–0.79; p=0.0003). Treatment with avelumab maintenance was found to be safe. Adverse events of any grade occurred in 98% of the avelumab plus BSC arm, with 47.4% grade ≥3; compared with 77.7% reported in the BSC alone arm, with 25.5% grade ≥3. The most commonly reported adverse events of grade ≥3 included urinary tract infection (4.4% versus 2.6%), anemia (3.8% versus 2.9%), fatigue (1.7% versus 0.6%), and hematuria (1.7% versus 2.6%), in the avelumab plus BSC versus BSC alone arms, respectively. The rate of immune-related adverse events was 29.4%, with 7.0% grade 3 and no grade 4/5 immune-related adverse events seen. The safety and significant survival benefit of this trial make the approach known as switch maintenance a new standard of care for all platinum-eligible patients in this setting.

Antibody–drug conjugates

Enfortumab vedotin

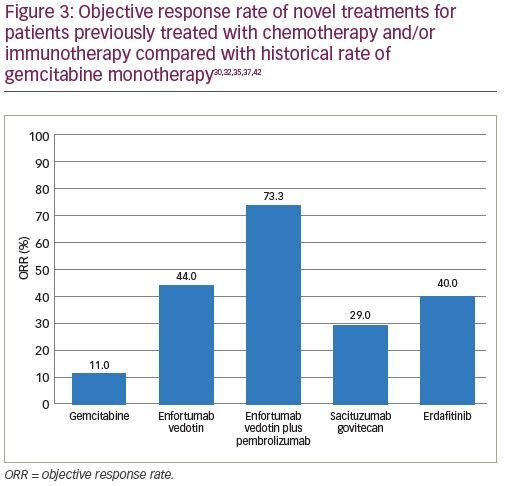

Enfortumab vedotin is an antibody–drug conjugate that is comprised of an antibody to Nectin-4 coupled with a microtubule disrupting agent, monomethyl auristatin E. Nectin-4, which is a transmembrane protein involved in processes associated with oncogenesis (Figure 1), is highly expressed in urothelial carcinoma.30 EV-201 is a phase II, single-arm study of enfortumab vedotin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.31 All patients enrolled were previously treated with platinum chemotherapy and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Enfortumab vedotin was given to 125 patients, and at a median follow up of 10.2 months the ORR was 44% (Figure 3). This compares favorably to the historical ORR to gemcitabine in this line of 10–15%.32 The median duration of response was 7.6 months. The adverse events that occurred most frequently were fatigue (50%; 6% grade ≥3), peripheral neuropathy (50%; 2% grade ≥3), alopecia (49%), rash (48%; 25% grade ≥3), decreased appetite (44%; 1% grade ≥3), and dysgeusia (40%). The findings from EV-201 lead to accelerated FDA approval of enfortumab vedotin, and the NCCN guidelines list it as a preferred regimen in third-line systemic therapy for locally advanced or metastatic disease.33,22

Given the encouraging data from trials evaluating enfortumab vedotin monotherapy, subsequent trials are investigating its use in combination with immunotherapy. The EV-103 trial, a phase Ib dose-escalation study, examined the combination of enfortumab vedotin with pembrolizumab.34 Initial data presented at European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2019 from cohort A (n=45), which consisted of patients who were cisplatin-ineligible and received enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab as first-line therapy, reported an ORR of 71% with a 13% CR rate. Updated safety and durability data from cohort A reported an ORR of 73.3% (Figure 3) in all patients with a 15.6% CR rate at a median follow up of 11.5 months.35 Patients with high PD-L1 status had an ORR of 78.6%, while those with a low PD-L1 status had an ORR of 63.2%. Among those patients that responded to this treatment combination, 18 (55%) have ongoing responses, with 11 patients demonstrating responses that have extended beyond 10 months. The most common adverse events included fatigue (58%; 11% grade ≥3), peripheral neuropathy (53%; 4% grade ≥3), alopecia (53%), rash (45%; 14% grade ≥3), and diarrhea (41%; 3% grade ≥3).34,35 These data suggest that the combination of enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab could confer a durable treatment response in cisplatin-ineligible patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Further phase II and phase III trials are ongoing to investigate these promising results.

Sacituzumab govitecan

Another novel antibody–drug conjugate, sacituzumab govitecan, is also being evaluated in the treatment of urothelial carcinoma. It is composed of a monoclonal antibody targeting Trop-2 (Figure 1) conjugated to the active metabolite of irinotecan (SN38). A phase I/II study of sacituzumab govitecan in heavily pre-treated patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma demonstrated clinical activity with an ORR of 31%.36 TROPHY-U-01 is a phase II trial in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma that is further evaluating the antitumor activity of sacituzumab govitecan.37 At a median follow up of 4.1 months, the ORR in cohort 1 of patients previously treated with cisplatin chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors was 29% (Figure 3), confirming the prior phase I/II study results. Clinically significant grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events included neutropenia (23%), febrile neutropenia (11%), anemia (17%), and diarrhea (11%). These early results will need follow up with larger trials to more completely evaluate the efficacy of this drug alone and in combination with other therapeutic agents.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors

FGFR genetic aberrations constitutively activate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, which promotes tumor cell proliferation, survival, drug resistance, angiogenesis, and immune evasion.38 Next-generation sequencing has demonstrated that FGFR alterations are common in urothelial cancer and are seen in approximately 23% of cases. Of these, FGFR3 mutations are most common (15%), followed by FGFR1 amplification (7%), FGFR2/3 fusions (6%), and FGFR3 amplifications (2%).39 Gene-expression profiling of urothelial carcinoma by The Cancer Genome Atlas identified five different subtypes, including luminal-papillary subtype, luminal-infiltrated subtype, luminal subtype, basal-squamous subtype, and neuronal subtype.40 Each of these have different prognoses and varying responses to therapy.41 According to this classification system, the luminal-papillary subtype is characterized by a high rate of FGFR3 mutations. In addition, FGFR mutations may be associated with lower sensitivity to immune checkpoint interventions.42

Erdafitinib

Erdafitinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of FGFR1–4 (Figure 1) that has demonstrated anti-tumor activity in patients with urothelial carcinoma.43 The BLC2001 Study was a phase II study of erdafitinib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with an FGFR3 activating mutation who had progressed on or after at least one prior course of chemotherapy.42 Prior immunotherapy was also allowed in this study. Of the total study population, 88% had been previously treated with chemotherapy and 22% had been treated with immunotherapy. Erdafitinib given at a dose of 8 mg by mouth daily demonstrated a 40% ORR (Figure 3), with a median PFS of 5.5 months and a median OS of 13.8 months. Patients harboring FGFR3 mutations had a higher ORR than those with FGFR2/3 fusions, 49% versus 16%, respectively. Treatment was discontinued in 13% of patients due to adverse events. The most common adverse events included hyperphosphatemia (77%; 2% grade ≥3), stomatitis (58%; 10% grade ≥3), diarrhea (51%; 4% grade ≥3), asthenia (20%; 7% grade ≥3), and hyponatremia (12%; 11% grade ≥3).

Based on the BLC2001 study, the FDA granted accelerated approval to erdafitinib for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with susceptible FGFR3 or FGFR2 genetic alterations that have progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy. Current FDA recommendations state that patients should be selected for therapy based on the FDA-approved companion diagnostic, therascreen® FGFR RGQ RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The NCCN guidelines list erdafitinib as a second-line alternative therapy post-platinum or post-checkpoint inhibitor for patients with susceptible FGFR3 or FGFR2 genetic alterations, and as a third-line preferred regimen for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.22

Other fibroblast growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors

Infigratinib is a selective FGFR1–3 inhibitor that is being evaluated in a phase Ib/II trial of 67 patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma.44 Patients were treated with infigratinib 125 mg by mouth daily for 3 weeks followed by 1 week off. Patients with FGFR3 alterations who were treated with infigratinib demonstrated a 25.4% ORR. Disease control rate, defined as CR plus partial response plus stable disease, was 64.2%. In patients with upper-tract urothelial carcinoma (n=8), the ORR was 100% with a median PFS of 8.5 months and OS of 21.8 months. In patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the median PFS was 3.65 months and OS was 7.0 months.

Pemigatinib is a potent oral competitive inhibitor of FGFR1–3 in urothelial carcinoma. Fight-201 is a phase II, open-label, multicenter study of pemigatinib in patients with metastatic or surgically unresectable urothelial carcinoma who harbor FGFR genetic alterations.45 Interim results were presented at ESMO 2018 and demonstrated an ORR of 25% for patients in cohort A, which included patients with FGFR3 mutations/fusions. Ongoing evaluations of these agents will provide further insight into the role of FGFR kinase inhibitors in the treatment of advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Conclusions

Although platinum-based chemotherapy still plays an essential role in the treatment of advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibody–drug conjugates, and FGFR kinase inhibitor therapies have expanded treatment options and altered treatment paradigms. In the first-line setting, platinum therapy followed by immune checkpoint inhibitor maintenance has emerged as a new standard of care for platinum-eligible patients. First-line immunotherapy is an option for those patients who are cisplatin-ineligible. In subsequent lines of therapy, there are multiple agents available to patients who are either ineligible for platinum-based therapy or who progress post-platinum therapy that have demonstrated improved tolerability and efficacy compared with single-agent cytotoxic chemotherapies, the prior standard. There are also ongoing trials investigating immunotherapeutic agents in combination with chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and antibody–drug conjugates. While these novel agents and combinations have offered hope for better outcomes in metastatic urothelial carcinoma, there remains a need for improvement. Many questions remain, including optimal duration of treatment, data directly comparing the efficacy of these therapies, and resistance mechanisms. Biomarkers will also likely play an increasingly important role in guiding therapeutic decision making in the future.