Currently, quality of healthcare is a hot topic, and this is especially true for cancer care. Patients try to seek the best care available. As a result, several ranking lists can be found on the Internet and in the popular press worldwide. Unfortunately, many of those lists do not meet the requirements needed for a fair comparison of healthcare providers and can therefore give misleading results. Nevertheless, the search for quality is plausible because there seem to be substantial differences in quality of care between countries, hospitals and doctors.1 In addition to patients, politicians, insurance companies and medical professionals also strive for a higher quality of care, all with their own reasons and strategies. In many countries, governments have tightened their existing regulations and created new ones when trying to improve quality of care in a ‘top-down’ manner. Obviously, medical professionals also put great effort into improving their quality of work, but this happens in a ‘bottom-up’ manner. All initiatives to improve quality of care can be nominated as ‘quality assurance’. Although lacking a strict definition, quality assurance can be summarised as “the complete set of systematic actions that is required to achieve a treatment result that meets a certain standard”.2

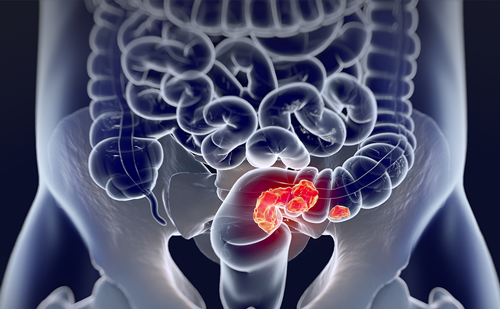

Quality assurance in surgical oncology is relatively new compared with other medical fields such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. For a long time, surgery was thought to have too much unexpected variation to be feasible for standardisation and quality control. However, the conception of surgery is steadily shifting from being a non-definable craft to a transparent and well-defined skill. Currently, many quality assurance programmes have been rolled out successfully in surgical oncology with encouraging results, in particular for the treatment of rectal cancer. In the early 1990s, the outcome after rectal cancer surgery was poor, with survival and recurrence rates of approximately 45%.3 In addition, there was a remarkable variation in outcome between hospitals and between individual surgeons.4,5 In that time the total mesorectal excision (TME) technique was introduced by Heald et al.6 Instead of a blunt dissection, the rectum is sharply dissected within its mesorectal fascia under direct vision. Many European countries initiated quality assurance projects as an answer to these challenges. In this article, we will describe different aspects of quality assurance, and will conclude with a framework for the future of surgical

To read full article please click here