A young patient was diagnosed with two synchronous colon cancers and found to be a MLH1 carrier diagnosing him with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome). Our patient suffered a cardiac arrest while on chemotherapy (capecitabine) and following cardiac investigations was found to have a long QT syndrome (LQTS) as well. There is no known link between these two conditions, but managing a patient with HNPCC and LQTS poses challenges.

Case History

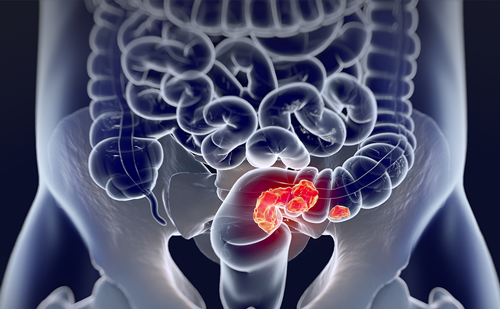

A 51-year-old male presented with a change in his bowel habit and was shown to have iron deficiency anaemia without blood in his stool. There was no family history of cancer, he was not on any medications and had no allergies. Of note was a history of faints. An initial diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was made and iron supplementation was prescribed. However with no improvement in symptoms, the patient was referred to gastroenterology for colonoscopy and the descending colon biopsy showed an adenocarcinoma. A pre-surgical electrocardiogram (ECG) was normal with a corrected QT (QTc) of 385 (see Figure 1). He underwent a subtotal colectomy and a diagnosis of two synchronous Dukes’ stage C (caecum and descending colon) cancers was made. Immunohistochemical (IHC) stains demonstrated a loss of staining for MLH1 and PMS2 in both cancers (see Figures 2a and 2b). Subsequent genetic testing has shown him to be a MLH1 mutation carrier. Following his surgery, the patient received four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with oral capecitabine (1,000 mg/m2) and intravenous oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2), called XELOX. XELOX-chemotherapy is delivered as a 3-weekly cycle with oxaliplatin administered on the first day of each cycle and oral capecitabine is taken twice daily for 2 weeks. Our patient tolerated XELOX-chemotherapy well and had no dose reductions. While taking capecitabine tablets as part of the fourth cycle, he unfortunately suffered a cardiac arrest in a public place, but was successfully resuscitated on site. Subsequent cardiac investigations including an adrenaline stress test using the Mayo protocol1 have led to the diagnosis of LQTS (see Figures 3a and b). Genetic analysis of the most commonly implicated genes, LQT genes 1–5, was negative but this does not exclude the presence of a less common LQT syndrome. One of our patient’s children was also found to have a positive adrenaline stress test and has been started on β-blockers. This strengthens the likelihood of an underlying genetic cause for the LQT syndrome. It was thought that the chemotherapy tablet capecitabine and/or the metic domperidome, given over 5 days at the beginning of each cycle at a dose of 20 mg three times per day, led to an unmasking of the thus far undiagnosed LQTS. Subsequently an implantable cardioverterdefibrillator was inserted and adjuvant chemotherapy was stopped. He has undergone genetic counselling for the inherited disorders and continued to attend oncological follow-up. He is now 2 years post the cardiac arrest, clinically well with a performance status of 0, and has no evidence of a cancer associated with HNPCC.

Hereditary Non-polyposis Colorectal Cancer

HNPCC, also known as Lynch syndrome, is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder that gives mutation carriers a high penetrance of colorectal cancer (approximately 80 %).2 The causative mutation is in one of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes3 resulting in microsatellite instability.4 An accumulation of DNA errors occurs in cells which contribute to tumorigenesis.3

HNPCC accounts for around 5 % of colorectal cancers,4 and its prevalence in the general population is similar to that of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.5 Patients with HNPCC usually present with colorectal cancer at a younger age (below 50 years) and the cancer tends to occur in the proximal colon.6 The risk of extracolonic tumours is increased.3

Genetic counselling of patients and families regarding HNPCC7 as well as regular cancer screening as per HNPCC guidelines are important in the management of such patients.8,9

Long QT Syndrome

LQTS is a disorder whereby ventricular myocyte repolarisation is prolonged predisposing the patient to life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia including torsades de pointes. The primary symptoms in patients with LQTS include palpitations, syncope, seizures and cardiac arrest. It is typically characterised by an increased QTc interval on ECG (>440 ms in men and 460 ms in women),10 and may be congenital or acquired. Congenital LQTS is a primary autosomal dominant inherited disorder with variable penetrance.11 The inherited mutations cause a loss or gain of function of the cardiac potassium, sodium or calcium ion channels.12 This can therefore affect the ventricular myocyte action potential. Congenital LQTS can be managed with a combination of lifestyle modifications, β-blockers and implanted pacemaker with a cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) when indicated.13 Acquired or druginduced LQTS can be caused by a large number of commonly prescribed medications, usually affecting the hERG potassium channel, resulting in ion channel-mediated ventricular repolarisation disturbances similar to those observed in congenital LQTS.14 Such drugs may unmask an underlying genetic predisposition to ion channel disease, or cause them de facto.

It is also well-recognised however that genotype-confirmed LQTS may be present in individuals with a normal QT interval at baseline.15 In these individuals a graded catecholamine infusion may be used to unmask latent LQTS, during which a lack of shortening of the QT or a paradoxical lengthening also supports the diagnosis.16

Discussion

The majority of colorectal cancers are sporadic. A small but significant minority of colorectal cancers occurs in patients with inherited genetic mutation such as in HNPCC or familial adenomatous polyposis. Due to the nature of its autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, it is important to recognise features of and confirm a diagnosis of HNPCC comprehensively, using the Amsterdam II criteria and the Revised Bethesda guidelines,17,18 as management encompasses not only the patient but the patient’s family as well.

The presence of two synchronous tumours in our young patient was highly suggestive of HNPCC and further tests including IHC and genetic tests could demonstrate the presence of a MLH1 carrier status. With a negative family history our patient is likely to be the index case necessitating future routine screening of his children19 and himself as per HNPCC guidelines.2,7,20

To our knowledge, this is the first case presentation of a patient suffering from Lynch syndrome as well as a LQTS. Although most unlikely, we contemplated the remote possibility of a link between these two genetic conditions.

The genetic basis of HNPCC is a DNA mismatch repair that causes subsequent abnormal DNA mutations not to be corrected. This mutation in particular leads to microsatellite instability that contributes to the pathway towards tumourneogenesis. In comparison, abnormal function of cardiac ion channels are the basis of LQTSs and do not have any reported association with tumourneogenesis. Based on the different pathoaetiology of each genetic condition, the two conditions are not linked and have co-existed unknowingly.

The identification of LQTS in our patient is most relevant towards the further management of HNPCC in our patient. Our patient was treated with adjuvant XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) chemotherapy. Capecitabine is known to be cardiotoxic21 and this risk of cardiac events increases if capecitabline is co-administered with oxaliplatin.22 Capectabine has also been reported to prolong QT interval in patients with existing coronary disease.23 Our patient had no past cardiac history. Oxaliplatin has been associated with abnormal conductance in sodium channels mainly resulting in neuropathy.24 Samol et al. have previously published a case report where oxaliplatin caused coronary artery spasms and speculated that this may have been due to voltage-gated Na+ channels.25 There have been two reports thus far of suspected oxaliplatin-induced LQTS in patients with lower gastrointestinal (GI) cancers.26,27 Anti-emetics, such as domperidone, are commonly prescribed to patients on chemotherapy to treat nausea. Domperidone is known to prolong the QT interval11 and hence should be avoided in patients with long QT interval. Recently, the Medicines and Health Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued a press release restricting the use of domperidome because of its increased risk of prolonged QT interval and arrhythmias.28 It is highly likely that chemotherapy and domperidone have unmasked the underlying LQTS in our patient.

The long-term management of our patient is being led by the oncology team with good liaison with cardiologists, geneticists and surveillance as per HPNCC guidelines.18,29 Chemoprevention with aspirin should be considered as there is good evidence that aspirin benefits patients with HNPCC as primary and secondary prophylaxes,30–32 as well as secondary prophylaxis in non-hereditary colorectal cancer patients.33 Aspirin reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with previous cardiovascular disease.34 A recent analysis of a large group of patients with prolonged QT interval showed that this population of patients had an almost three-time increased risk of stroke than thought with normal QT interval.35 It is therefore logical to assume that aspirin prevents cardiovascular events in patients with LQTS. These data provide strong evidence that the use of aspirin is beneficial in our patient, the difficulty will be deciding on the dose. The available data were discussed with the patient and he was started on aspirin 75 mg once daily.

Conclusion

We present the first case report of a young patient who has HNPCC and co-existing LQTS, both are genetically inherited conditions but unrelated. The LQTS prevented further administration of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Family screening was performed, where indicated, in conjunction with genetic services following national and international guidelines. Our patient was started on chemoprevention with aspirin and is undergoing regular surveillance according to HNPCC guidelines.