The incidence of melanoma is high and is the sixth most common cancer in US men and eighth most common cancer type in US women.1,2 Moreover, the incidence of metastatic melanoma has been increasing worldwide at a rate faster than any other solid malignancy.3 There were an estimated 76,250 new cases of melanoma and 9,180 deaths from the disease in the US alone this year.4 Melanoma has been shown to affect a large number of younger patients and thus it is one of the leading cancers in terms of patient years-of-life lost.5

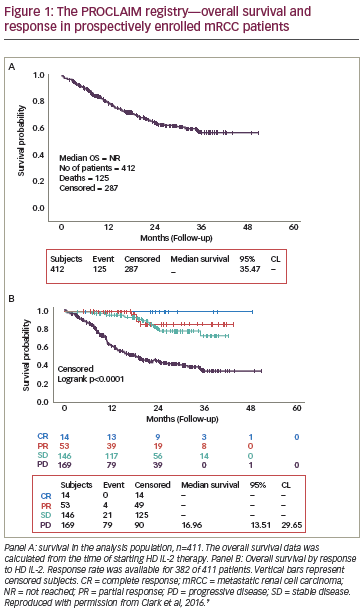

The prognosis for patients with metastatic disease has traditionally been poor with a median survival of approximately 6–9 months due to lack of effective therapeutic options.6,7 Indeed, no therapy had ever shown a survival advantage for patients with advanced melanoma until 2011. Survival for patients with stage III disease is quite varied as patients with low tumor burden (stage IIIa) do much better than those with multiple lymph node metastases or in-transit metastases (stage IIIb/IIIc disease).8

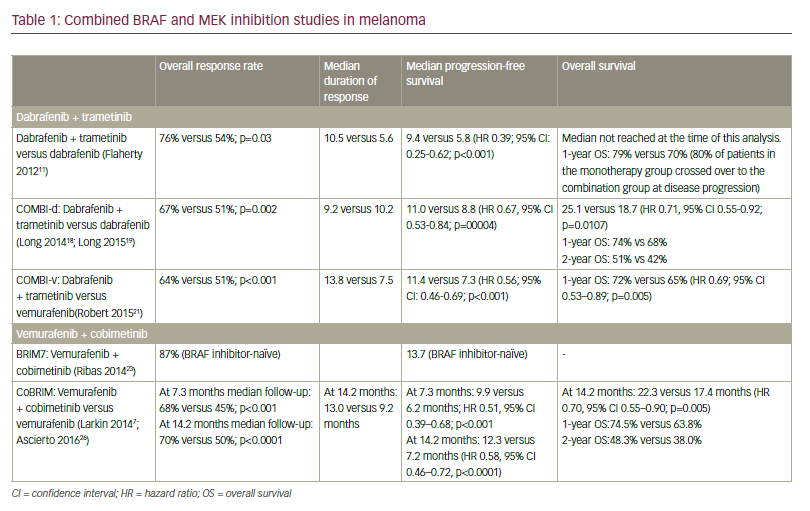

While melanoma has been resistant to chemotherapy, it does express tumor-specific antigens that have made immunotherapy a viable treatment option. Key research in determining gene mutations that drive melanoma growth have been instrumental in helping to develop targeted therapies that show great promise in treating patients with advanced disease. Two new agents, ipilimumab and vemurafenib, have recently received approval based on clinical evidence that they impart a statistically significant survival advantage over control patients receiving vaccine or chemotherapy. Appropriate combination and sequencing of old and new agents holds the promise of increasing the number of complete durable responses.

The paradigm shift for melanoma will be to consider long-term durable responses and a potential cure of the disease as the goal of future therapeutic trials, rather than simply palliation. This article provides an overview of traditional and emerging management approaches as well as reviews strategies for combining and sequencing available treatments to optimize outcomes.

Challenges in Treating Metastatic Melanoma

Melanoma is a particularly difficult disease to manage for several reasons. Firstly, it has a high metastatic potential with a tendency to disseminate to distant sites, often including the brain, via hematogenous and lymphatic channels leading to poor prognosis.9 It is the only cancer where millimeters (not centimeters) of tumor are used in the staging system, with a 4 mm melanoma imparting as much risk as a 10 cm lung tumor. Furthermore, melanomas can downregulate patients’ own intrinsic immune system pathways creating both a local and systemic immune-depleted state.10

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.