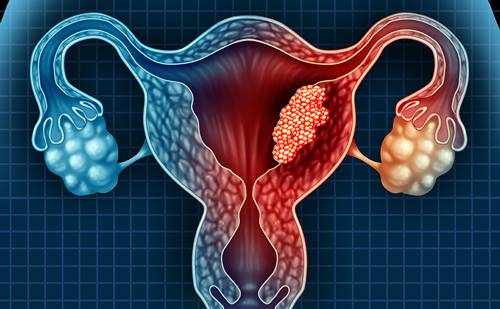

Cervical cancer (CC) is a leading cause of cancer morbidity in women globally. In Europe, epidemiological data on CC incidence shows important differences between countries: from 3.6 per 100,000 women in Switzerland to 28.6 per 100,000 in Romania.1,2 In 2015 in the Republic of Belarus, the morbidity and mortality rate from CC were 11.9 and 4.2 per 100,000 of the female population, respectively. In addition, 32.7% of cases of CC in Belarus are diagnosed at advanced stages (III–IV) of the disease, and the majority of women presenting have at least locally advanced (stage IB2 or greater) CC.3 One serious complication of locally advanced CC is haemorrhage from tumour, which in 11% of patients is massive and life threatening, requiring performance of emergency haemostatic interventions and interruption or delay of antineoplastic therapy, leading to a poorer prognosis.4–7

Haemorrhage from a cervical tumour can be difficult to control due to the extensive and richly anastomotic blood supply to the uterus and cervix, which can often be compounded by the development of neovasculature associated with the malignancy. Conservative management for arresting uterine/cervical haemorrhage in this clinical situation is, as a rule, ineffective, and the risk of complications of surgical intervention in the presence of anaemia, a massive tumour and possible parametrial involvement is often prohibitively high. Additionally, laparotomy with ligation of the internal iliac vessels does not always lead to haemostasis, as the anastomotic blood flow is often quite extensive and is not interrupted.8

The recent advances in angiography have made it possible to control pelvic haemorrhage through radiologically guided occlusion of the branches of the internal iliac arteries.9–12 In gynaecologic oncology practice, pelvic artery embolisation (PAE) has generally been deemed to be a palliative procedure up til now, not as a component of antitumor therapy;13,14 however, in our experience, PAE can also be used to rescue patients before proceeding or continuing with definitive therapy for their CC. Here we review our experience with PAE at the NN Alexandrov National Cancer Centre in Minsk, Belarus.

Materials and methods

Patients

A retrospective study was performed of consecutive patients who underwent PAE between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2015 at the NN Alexandrov National Cancer Centre of Belarus. Patients were identified through the cancer centre database: 68 patients with primary locally advanced CC with the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages IIB–IVB and 24 with vaginal bleeding from recurrent tumours of gynaecologic and non-gynaecologic malignancies. Only patients with biopsy-confirmed CC were included in our analysis. Nine patients were excluded due to having gynaecologic malignancies other than CC and two due to having non-gynaecologic tumours. The clinical data was abstracted from medical records of all eligible patients. Inpatient and outpatient records – including clinic notes, operative reports, pathology reports, radiology reports and hospitalisation notes – were reviewed for primary tumour characteristics, treatment history, procedure details, complications and outcomes.

Treatment

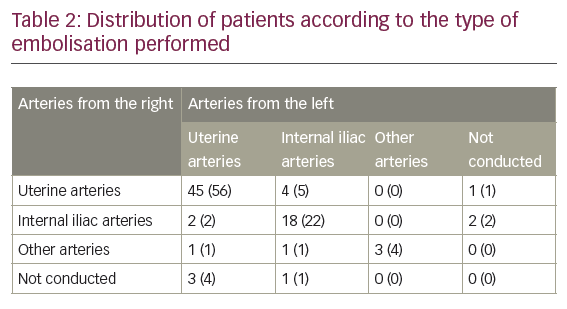

All procedures were carried out according to emergency indications associated with life-threatening haemorrhage in the angiography suite, with the use of local anaesthesia by experienced interventional radiologists. Pelvis angiography was conducted according to standard methods using catheterisation of femoral or axillary artery using the Seldinger technique. Embolic agents were used in various combinations to achieve full occlusion of the involved vessels. If it was technically possible, radiological endovascular haemostasis was performed on both sides; otherwise a unilateral procedure was performed. Fifty-six percent of patients underwent selective embolisation of the uterine arteries from both sides; in the other cases embolisation of the branches of the internal iliac arteries or other pelvis arteries supplying the tumour was conducted.

Statistical methods

Basic descriptive statistics were used to describe the patients’ clinical characteristics. Adjusted survival was defined as the time from the PAE to death from underlying disease, the last observation or death from other causes. Survival rate was calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method. A log-rank test was used to compare survival rates between two groups, in three groups – χ2 criterion was used. All p-values were two-sided, with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with TIBCO Statistica™ (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Results

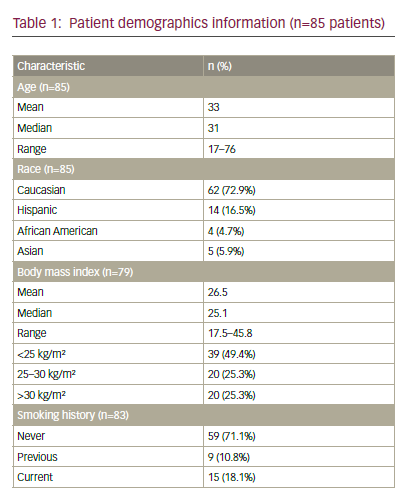

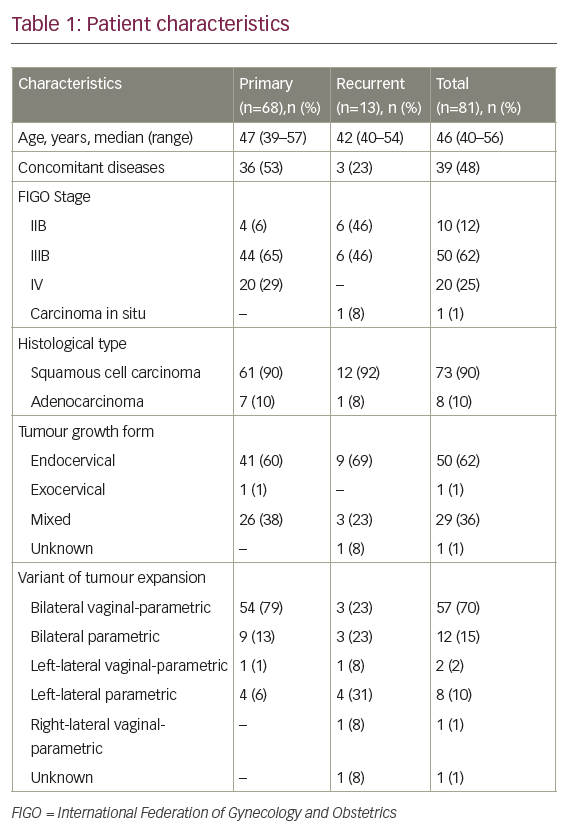

In total, 81 eligible patients were included in the study: 68 (84%) with primary disease and 13 (16%) with recurrent disease. The patient characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Stage IIB was diagnosed in 10 (12%) patients and stage IIIB in 50 (62%) patients. There were only two patients with stage IVA disease and they were therefore analysed together with patients with stage IVB disease (n=18, 22%). Nine percent of patients had grade 1 tumours, 69% had grade 2 tumours and 22% had grade 3 tumours.

The median operative time of PAE was 103 minutes (range 40–195 minutes). The procedure was performed bilaterally in 74 patients (91%) and unilaterally in seven patients (9%); of those, on the procedure was performed on the right side in three patients (4%) and on the left side in four patients (5%). In 45 patients (56%) selective embolisation of the uterine arteries from both sides was performed; in 18 (22%) embolisation of the distal branches of the internal iliac arteries on both sides was performed; in six patients (7%) embolisation of the uterine artery on one side and the distal branch of internal iliac artery from the other side was performed, either because of a more extensive vascularisation in one of the parametria or because the tumour was not supplied in that side by the uterine artery. A more detailed distribution of patients according to the type of embolisation performed is provided in Table 2.

For embolisation of pelvic arteries, a femoral approach was used in 58 patients (72%) and an axillary approach in 23 (28%). Sixty-three patients (78%) were given transfusions during their care.

Pelvic artery embolisation controlled vaginal bleeding in 76 patients (94%). In five patients (6%) haemorrhage recommenced within 1–24 days, which required a repeat procedure. Four of these five patients had primary disease and one had disease recurrence. In the patients with primary disease, a repeat intervention was executed within 6–24 days (average term was 17.5 days), and in the recurrent disease patient, it occurred the next day. In all patients, the first procedure was performed in full on both sides. A repeat bilateral embolisation was performed in two patients, while in two others a unilateral procedure was performed. The patient with recurrent disease had invasion of tumour into the bladder. After bilateral embolisation of the anterior division of internal iliac arteries, haemorrhage from recurrent tumour in the bladder recommenced the next day and a transurethral resection of the tumour in the bladder was performed.

There were no serious intraoperative complications associated with the PAE procedures performed. One patient died from thromboembolism of the pulmonary artery branches within 24 hours of the procedure. Post-embolisation syndrome was observed in all patients in the form of pain of various intensities over 1–3 days and was managed by administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients also experienced fever, general weakness, malaise and loss of appetite. These symptoms were managed conservatively.

After successful PAE, 46 of 68 patients (68%) were able to continue radiotherapy treatment a median of 3 days after treatment (range 1–17 days). Primary treatment was completed in 43% of patients (29 of 68). Ten additional patients (15%) were able to complete external beam radiotherapy but brachytherapy could not be completed due to extensive, friable tumour.

Survival

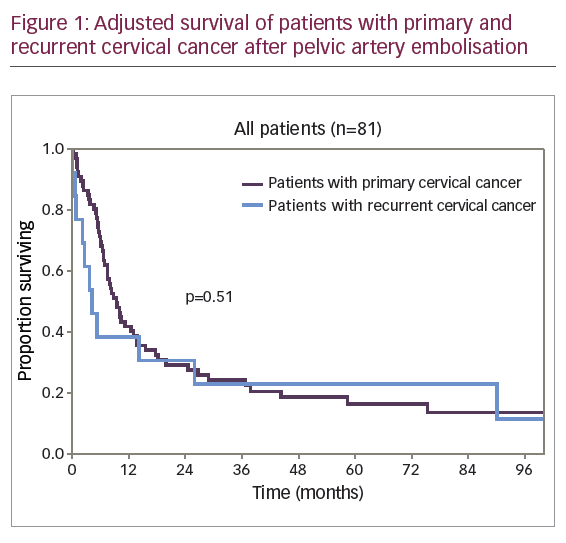

The median follow-up period for 80 of the 81 patients included in the study was 66 months (30.8 to 102.0 months). One patient was observed for 6 months, after which she left the Republic of Belarus. During the follow-up period, 67 patients (83%) died of disease and 4 patients (5%) died of other causes. The adjusted 1-year survival rate was 41.4% (standard error [SE] 5.6%), the 5-year survival was 17.9% (SE 4.5%), and the median adjusted survival rate was 8.4 months.

A diagram of adjusted survival rate of patients with primary and recurrent disease is provided in Figure 1.

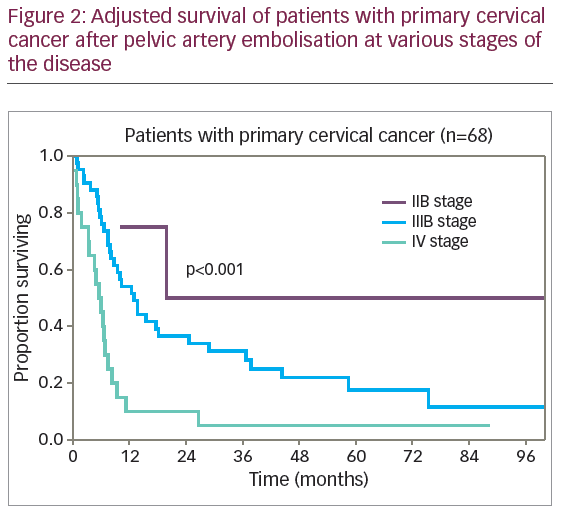

The difference in survival rates of patients with primary and recurrent CC was not clinically or statistically significant (p=0.51). The diagrams of adjusted survival rate of patients with primary disease by stage are provided in Figure 2.

The difference in survival rates of patients with primary disease by stage of disease was statistically significant (p<0.001): 1-year adjusted survival rate of stage IIB, IIIB and IV disease was 75% (SE 22%), 54.1% (SE 7.8%), and 10.0% (SE 6.7%), respectively. The 5-year survival rate was 50% (SE 25%), 17.6% (SE 6.7%), and 5.0% (SE 4.9%), and median adjusted survival rate was 19.9 months, 12.8 months, and 5.5 months, respectively.

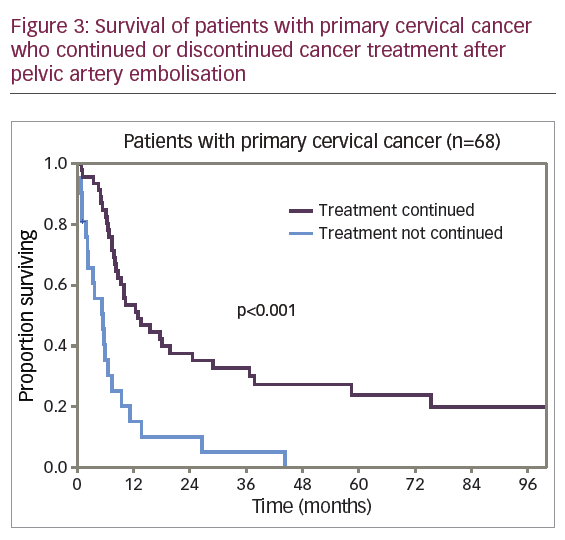

For the 68 patients with primary disease, PAE was performed urgently prior to radiation therapy in 42 patients (62%) and at various stages during the treatment in 26 patients (38%). After PAE, 46 patients (68%) continued treatment and 22 patients (32%) received no further cancer therapy. Figure 3 shows the adjusted survival rates for patients who continued and those who discontinued cancer therapy.

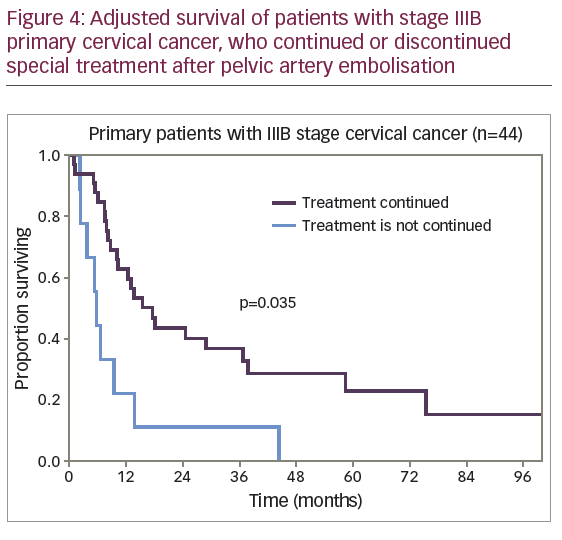

The differences in survival rate were significantly lower for the 22 patients (32%) who discontinued cancer therapy compared with the 46 patients (68%) who continued treatment. The 1-year adjusted survival rate was 15.2% (SE 8.1%) and 53.5% (SE 7.4%), respectively. No patient survived to 5 years in the first subgroup; in the second subgroup a 5-year adjusted survival rate was 24.0% (SE 6.8%). The median adjusted survival rate was 5.4 months for the first subgroup and 12.8 months for the second subgroup (p<0.001). However, among the patients who discontinued cancer treatment, 50% (11 of 22) were patients with stage IV disease, while in the second subgroup 20% of the patients (9 of 46) had stage IV disease. To level the data on differences, comparison of survival rate was conducted for patients with stage IIIB disease, the most represented in the study cohort of patients with primary CC (Figure 4).

The median adjusted survival rate was 5.5 months for patients with stage IIIB disease who discontinued cancer treatment and 15.7 months for patients who continued treatment (p=0.035).

Discussion

The results of the present study are based on a wide experience of PAE in patients with locally advanced and recurrent CC complicated by haemorrhage. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest reported series of PAE of patients with haemorrhage from CC, and the only series to evaluate the effect of this procedure on the continuation of definitive therapy and survival. Previous reports on the control of haemorrhage by PAE have demonstrated the feasibility of this intervention. Albu et al. reported one case of radiological endovascular haemostasis with use of occlusion of uterine arteries in a patient with CC, with subsequent conduction of radiation therapy and performance of radical hysterectomy at 6 weeks.6 Çaypınar et al. also reported one case of a patient with stage IVA CC who presented with life-threatening haemorrhage resistant to conservative haemostatic treatment.4 Pelvic artery embolisation of small pelvis arteries was performed. The procedure was palliative and further treatment was not conducted. Tinelli et al. provided the results of successful embolisation of 10 primary patients with gynaecological cancer, of whom only three had CC, the remaining seven had endometrial cancer (four cases) and uterine sarcoma (three cases).7 There was no information available on further treatment. Nogueira-García et al. provided data on six primary patients with locally advanced CC who underwent radiological endovascular haemostasis with palliative purpose; from that time on no antineoplastic therapy was given.14

Our results demonstrate that in patients with locally advanced and recurrent CC complicated by haemorrhage, radiological endovascular embolisation of small pelvis arteries has high efficiency – in 94% patients (95% confidence interval [CI] 86–98%), the haemorrhage stopped and only 5 patients (6%) required a repeat procedure.

The long-term treatment outcomes in the present study are certainly poor. However, the category of patients should be considered, which included patients with primary extremely advanced CC (stage IIIB: 44 patients [54%]; stage IV: 20 patients [25%]), as well as with disease recurrence after previous treatment of stage IIIB carcinoma (6 patients [7%]). All these patients had low cure rates until recently.

According to our results, the difference in the survival rate of patients with primary and recurrent CC is not clinically or statistically significant (p=0.51). The absence of significantly better results of treatment of patients with primary CC in comparison with recurrent could be explained, in our opinion, by the fact that primary patients are represented by disease stages with extremely unfavourable prognosis – nearly one third of patients (29%) had stage IV disease, and 26% (18 of 68) had stage IVB disease.

The conduction of special antineoplastic therapy has significant impact on long-term treatment outcomes of primary patients with locally advanced CC, which is impossible in the presence of haemorrhage from tumour. The present study showed that performance of radiological endovascular embolisation of small pelvis arteries to arrest haemorrhage allowed 68% (48 of 68) of patients with primary CC (95% CI, 55–78%) to begin or continue previously started antineoplastic therapy in the short term: up to 3 days later in 50% of patients and 3–6 days later in 25%. This demonstrates a small injury rate and high efficiency of method. The adjusted survival of patients who continued treatment and completed it in full with external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy (29 patients, 43%) is rather high: the 1-year adjusted survival rate was 71.4% (SE 8.5%), the 5-year adjusted survival rate was 34.3% (SE 9.2%) and the median adjusted survival rate was 19.9 months.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature. In addition, our findings are from a high-volume highly specialised cancer centre, and thus our findings might not be easily replicated in smaller centres. However, our results suggest that PAE in patients with locally advanced and recurrent CC, complicated by haemorrhage, is well tolerated, minimally invasive and highly effective, and can be used at any stage of treatment in this category of patients. In a significant minority of our patients, definitive therapy was initiated or continued after embolisation, and led to significantly improved patient survival. Therefore, pelvic haemorrhage in a patient with advanced or recurrent CC should prompt referral to a specialty centre for consideration of PAE.