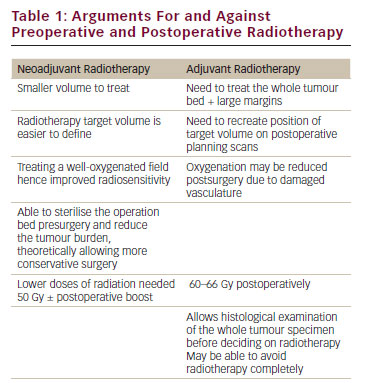

Approximately 70–80 % of patients with advanced prostate or breast cancer and 30–40 % of patients with advanced lung cancer and other solid tumours develop metastatic bone disease (MBD).1 The added burden to patients once cancer afflicts bone is significant. In addition to the reduced survival associated with bone metastases, systemic morbidity such as bone pain is common.1 Other complications directly related to metastatic bone destruction include: pathologic fracture, spinal cord compression, that can result in numbness or weakness, urinary or faecal incontinence or paralysis, and hypercalcaemia of malignancy.1 All these problems can have a deleterious impact on the quality of patients’ lives. Irradiation of the bone (e.g., for bone pain or fracture), surgery to the bone to prevent or treat fracture, pathologic fractures and spinal cord compression are conditions labelled collectively as skeletal-related events (SREs).2 While the term SRE is commonly used to quantify the effects of MBD, additional symptoms from disease in the skeleton, such as pain and impaired mobility, can occur irrespective of the presence of SREs. Indeed, prognosis is diminished for patients with MBD who develop SREs compared with those who do not.2,3 Furthermore, the overall cost of the treatment of SREs places a significant burden on healthcare systems.4–7 In addition to appropriate systemic antitumour therapy to palliate symptoms and prolong life-expectancy, delaying or preventing SREs with bone-targeted agents is important. A key approach is the use of drugs to reduce osteoclast-mediated bone destruction (see Table 1).8–11

A number of agents classified as bisphosphonates bind to bone and are toxic to osteoclasts, reducing their bone-resorbing effects and thereby decreasing SREs. Bisphosphonates vary in their mode of administration, but also in their degree of potency, toxicity and effectiveness according to tumour type. For example, clodronate is administered orally, ibandronate is available in both oral and intravenous formulations, and pamidronate and zoledronic acid are both administered intravenously. (ibandronate, pamidronate, zoledronic acid) are considered more potent than earlier generation drugs such as clodronate and have different side-effect profiles. While approvals by cancer type are country- and region-specific, ibandronate, clodronate and pamidronate have demonstrated efficacy in patients with metastatic breast cancer and bone lesions from multiple myeloma. Zoledronic acid is approved to prevent SREs (including tumour-induced hypercalcaemia) in patientswith advanced malignancies involving bone.

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.