Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) comprises ~6 % of all Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with a median age at presentation of mid-60s. It is characterised by the t(11;14)(q13:32) translocation, which leads to overexpression of cyclin D1 resulting in subsequent dysregulation of the cell cycle and of several intracellular survival pathways.1 Although the survival of MCL patients has been demonstrated to have improved over the last decade it is still considered incurable, typically relapsing multiple times with increasingly chemotherapy refractory disease.

For younger, fit patients there is a significant benefit to overall survival (OS) with the incorporation of high-dose cytarabine to upfront treatment for MCL2–4 and consolidation of treatment with a high-dose autologous stem cell transplant further significantly prolongs the duration of remission.5 The median age at diagnosis, however, means that the majority of patients are ineligible for such therapies. For these patients either anthracycline, purine analogue or, more recently, bendamustinebased therapies have been used. Randomised data have demonstrated a superior OS for R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) compared with R-FC (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab) and this can now be considered the standard of care for elderly patients unable to receive high-dose regimens.6 There is also a role for maintenance therapy with rituximab in patients who are not eligible for autograft consolidation, to further prolong the duration of remission.6 A small subset of MCL patients will have disease that behaves indolently and these can safely be managed with a watchful-waiting approach initially.7

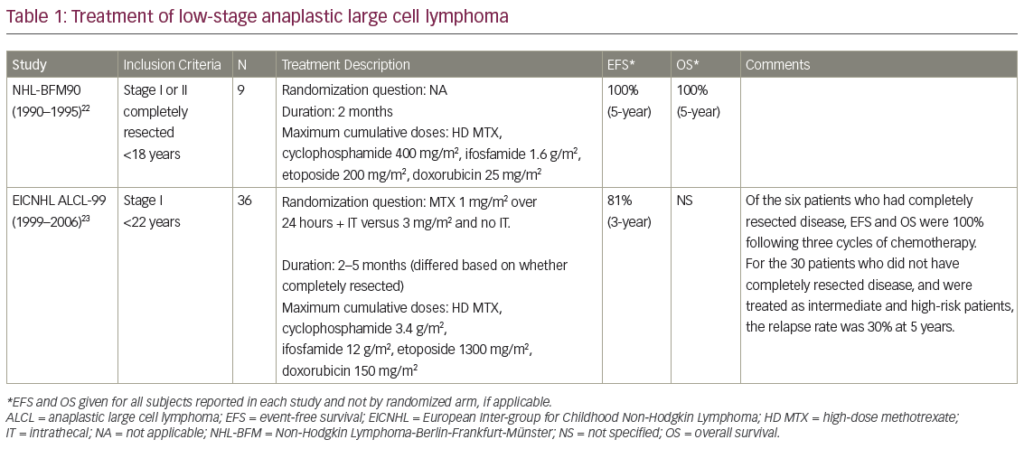

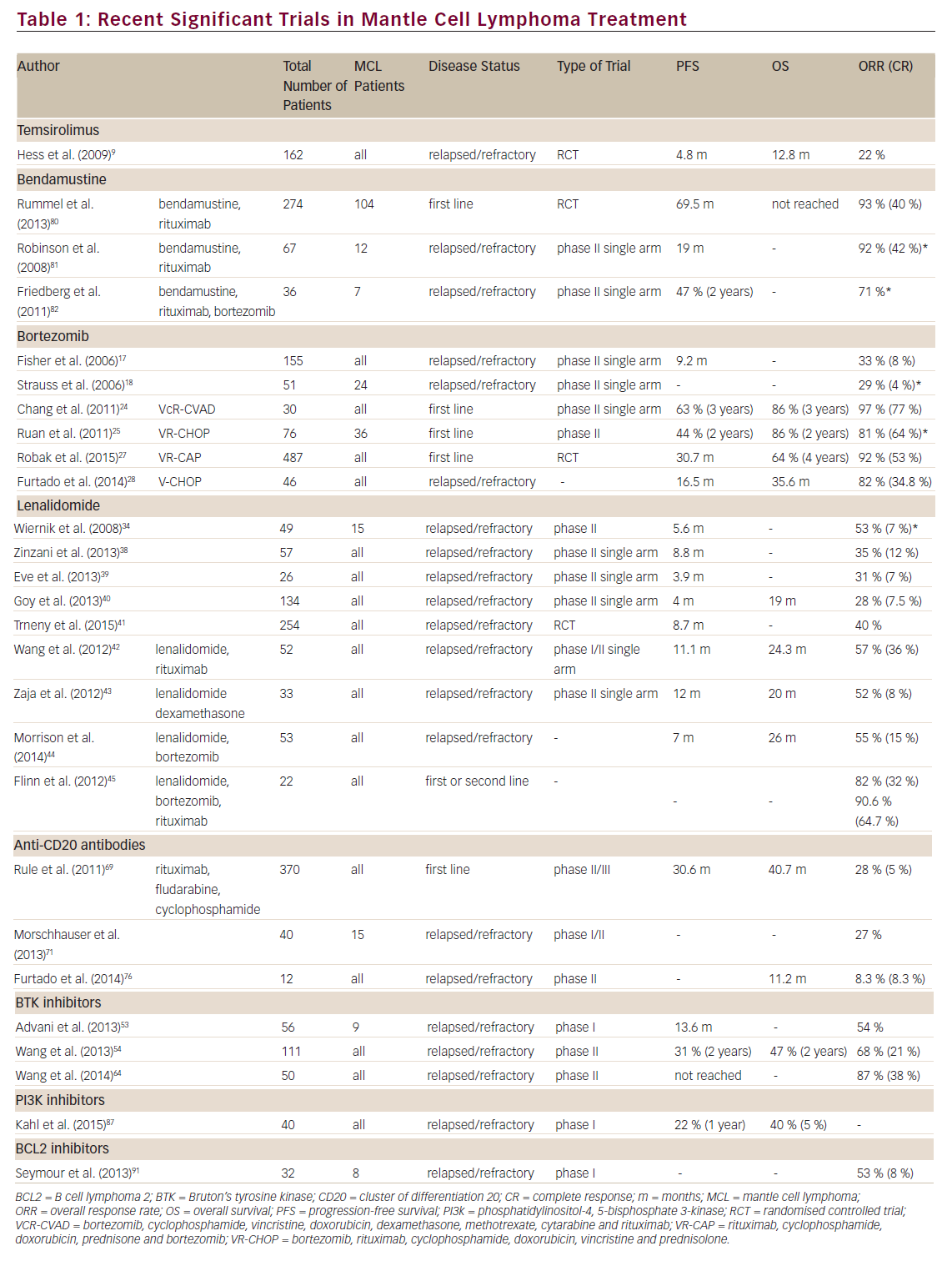

The treatment of first and subsequent relapses however is less well defined, with many regimens being commonly utilised, depending on the performance status of the patient and prior chemotherapy exposures. In general, the disease becomes more refractory to chemotherapy with each relapse and it is in this setting that the treatment options have recently expanded with many newer agents showing significant activity against MCL. Here we review the available data on some of these treatments, including the four approved drugs for use in this setting (temsirolimus, bortezomib, lenalidomide and ibrutinib) (see Table 1).

Temsirolimus

Temsirolimus is a selective inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), interfering with the ability of the cells to translate essential proteins.8 This disruption extends to cell cycle regulating proteins, including cyclin D1, which is overexpressed in MCL due to the t(11:14)(q13:32) translocation, which is the hallmark cytogenetic abnormality associated with this disease. This drug received its European licence for the treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL on the basis of a phase III randomised trial comparing temsirolimus with investigators choice of single-agent chemotherapy (from a permitted list).9 The most commonly chosen agents were gemcitabine or fludarabine. The temsirolimus therapy (at the currently recommended dose of 175 mg for 3 weeks followed by 75 mg weekly) led to a higher overall response rate (ORR) (21 %) compared with investigators choice (2 %). However, the ORR is very similar to that seen in phase II studies of the two most commonly chosen agents in the comparator arm (25–33 %).10,11 The trial also demonstrated a small (but statistically significant) increase in median progression-free survival (PFS) of 4.8 months with temsirolimus from 1.9 months with investigators choice.

Despite being licensed for this disease, the small benefits achievable with it, combined with the significant side effects noted (marked hyperglycaemia and lipidaemia, severe thrombocytopenia and asthenia)9 and its intravenous mode of administration have limited the use of this drug for MCL management.

Bortezomib Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor that selectively and reversibly inhibits the 26S proteasome, leading to cell cycle dysregulation and increased apoptosis.12,13 The 26S proteasome is key in the degradation of intracellular proteins including the inhibitor (IkB) of nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB) and p53.14 Inhibition of the degradation of these reduces the NFkB response to cellular stresses. Proteasome inhibition also increases apoptosis by interfering with the unfolded protein response thereby increasing endoplasmic reticulum stress and by increasing the levels of death receptors DR4 and DR5, which sensitises cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis.14,15

While its main use has been in the treatment of multiple myeloma, bortezomib has shown efficacy in the treatment of many NHL subtypes and has demonstrated significant single-agent activity in MCL with ORR of 29–41 % (complete response [CR] 4–8 % ).16–18 On the basis of this, bortezomib was granted US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of relapsed MCL in December 2006.

Preclinical data suggests that bortezomib increases cell sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy providing a rationale for its inclusion into combination chemotherapy regimens.12,19,20 Consequently, multiple regimens are being explored in several NHL subtypes.21–24

Significant benefit has been demonstrated when bortezomib is added to upfront treatments for patients with newly diagnosed MCL. Adding bortezomib to the intensive R-hyper (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, methotrexate, cytarabine and rituximab) CVAD (VcR-CVAD) regimen followed by maintenance rituximab showed a high ORR of 97 % with 77 % CR and a 3-year PFS and OS of 63 % and 86 %, respectively.24 A phase II trial combining bortezomib with R-CHOP in newly diagnosed MCL patients has also shown a high response rate (CR/CRu [CR, unconfirmed] rate 72 %) and an increase in 2-year median PFS from 16.6 to 23 months compared with similar historical studies of R-CHOP induction for MCL.25,26 As expected, VR-CHOP (bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) caused a slightly higher incidence of peripheral neuropathy than seen with R-CHOP alone; however, the majority of this was low grade.

A recently published trial substituted bortezomib (VR-CAP) for vincristine in the standard R-CHOP regimen for front-line MCL treatment. In this trial 487 patients were randomised between VR-CAP and R-CHOP. The trial demonstrated a significant increase in PFS from 14.4 months with R-CHOP to 24.7 months with VR-CAP and a significantly higher CR rate (42 % versus 53 %). The toxicity of adding bortezomib to R-CHOP was a marked increase in haematological suppression with 57 % of VRCAP patients experiencing severe thrombocytopenia compared with 6 % of the R-CHOP patients. The incidence of peripheral neuropathy in both groups was similar.27

In relapsed disease the addition of bortezomib to CHOP chemotherapy markedly increases the ORR (47 % versus 82 %) with a significant improvement in OS (11 months versus 35 months).28 Good outcomes have also been seen with its combination with a variety of other chemotherapeutic regimens (rituximab,29 gemcitabine,30 zevalin31).

A concern with the use of bortezomib is its toxicity profile, with haematological and neurological toxicity being the most frequent adverse effects reported. Delivering bortezomib subcutaneously rather than intravenously is likely to significantly reduce neurological toxicity without compromising efficacy, as has been shown in multiple myeloma.32

Lenalidomide

Lenalidomide is a second-generation immunomodulatory agent derived from thalidomide.33 Although it is used extensively in a variety of haematological malignancies its mechanisms of action remain to be fully determined. It is known to have direct anti-tumour effects and to modulate the immune system and bone marrow microenvironment, altering T cell and natural killer (NK) cell activation, cytokine production and angiogenesis. The extent to which each of these varied mechanisms exert their effects appears to be disease specific.

Despite some impressive results in myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), lenalidomide has not shown quite such promise in NHL. In phase II studies of lenalidomide monotherapy in various subtypes of both indolent and aggressive lymphoma the observed response rates were 23 % in indolent disease and 35 % in aggressive disease, although many indolent patients experienced stable disease.34–36 For a reason that is not yet entirely clear, MCL appears to respond better than many other NHL subtypes to lenalidomide treatment. The MCL subset of the NHL-002 trial experienced a significantly higher response than the overall cohort (ORR 53 %)37 although in the much larger MCL cohort of NHL-003 the ORR was lower (35 %) but with a longer duration of response of 16 months.38 This is similar to the 31 % ORR demonstrated utilising a different dosing schedule (25 mg/day for six cycles followed by 15 mg daily as maintenance until progression).39

In a cohort of heavily pre-treated patients who had all received prior bortezomib therapy, the EMERGE study showed an ORR of 28 % (CR 7.5 %) with single-agent lenalidomide. The median duration of response in this setting was 16 months.40 Based on these results, the FDA approved the use of lenalidomide for MCL patients in second relapse who had previously received treatment with bortezomib. Recently, the multicentre randomised SPRINT trial of 254 patients has demonstrated a benefit for lenalidomide compared with investigator choice with a significant increase in PFS (8.7 versus 5.2 months; p=0.004) and response rates (ORR 40 % versus 11 %; p=<0.001).41 Strikingly the median duration of response (16 months) was almost identical to that observed in previous studies40–42 demonstrating that there are a group of patients who do extremely well with this agent. Unfortunately we are unable to identify these patients prior to therapy.

In all trials of the drug so far, lenalidomide is generally well tolerated with the main toxicities being haematological suppression and fatigue. Neuropathy and thrombosis are less commonly seen than with thalidomide.

The combination of lenalidomide and rituximab shows increased efficacy in MCL, with an ORR of 57 % and OS of 24.3 months. Side effects from this combination are predominantly haematological with over half the patients experiencing grade 3–4 neutropenia.42 Similar response rates are seen when lenalidomide is combined with dexamethasone (52 %).43

The combination of lenalidomide and bortezomib is clearly attractive as both drugs have single-agent activity in MCL. However, in a phase II trial of this combination the observed ORR was only 40 %, which is similar to what might be expected with either drug when given as a single agent. In addition there was significant associated toxicity, leading to one-third of the patients discontinuing treatment.44 Use of a much lower dose of lenalidomide (10 mg/day rather than 20 mg/day) in combination with bortezomib and rituximab was better tolerated and demonstrated a much higher ORR of 82 % (CR 32 %).45

The phase I part of a trial of lenalidomide with bendamustine + rituximab (LENA-BERIT) showed that the addition of lenalidomide can produce very high ORR (100 %), but does add toxicity of which there was a higher than expected incidence of allergic/cutaneous reactions in cycle one. The maximum tolerated dose was 15 mg/day lenalidomide.46 The recent report of the combination of rituximab and bendamustine with low-dose lenalidomide (10 mg for four cycles and 15 mg thereafter in responding patients) resulted in high response rates with a significant proportion achieving molecular remission.47

With the current evidence it appears that single-agent lenalidomide has a good efficacy in MCL; however, when used in combination with other agents a lower dose of lenalidomide is required due to the attendant toxicity.

Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) mediates downstream activation of the B cell receptor and is a critical component in cell survival signalling pathways, which are critical for maturation and functioning of normal B cells.48 The viability of various NHL subtypes is dependent on the maintenance of functional B cell receptor signalling49 and it is now known that constitutive activation of components of this pathway occur in MCL.50–52 The first BTK inhibitor to reach clinical use, ibrutinib, is now approved for the treatment of relapsed MCL and CLL (or first line in CLL with p53 or 17p mutations) and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia.

The phase I trial of ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory B NHL demonstrated a 54 % ORR, with seven of the nine MCL patients responding.53 A subsequent phase II multicentre international trial of ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory MCL confirmed its high activity in this disease with an ORR of 68 % (CR 21 %, PR 47 %).54 The 2-year outcomes from this trial have shown a 47 % OS with 31 % PFS. In the study, 22 % of patients were maintained on ibrutinib for >24 months.55 This high efficacy occurred despite this being a cohort of highly pre-treated patients, with the majority having advanced disease at the time of trial entry and 45 % having disease refractory to the previous line of treatment. Of particular note, for a drug being used in the setting of multiply relapsed disease is the demonstration of efficacy irrespective of prior therapies received, including bortezomib and lenalidomide. Indeed a trial of single-agent ibrutinib in patients whose disease had progressed on bortezomib showed a 62 % ORR with 20.9 % CR.56

The toxicity profile of ibrutinib is very modest with the most common adverse events being fatigue, diarrhoea and nausea. Significant bleeding and the development of atrial fibrillation have been seen in around 5 % patients and can lead to the discontinuation of the drug.

BTK inhibition has been demonstrated to affect adhesion of the malignant cells in CLL,57 while in MCL there is clear evidence of a reduction in plasma chemokines and in the expression of chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor type 4 (CXCR4), involved in the homing of cells to lymphoid tissues.58 In both conditions it has been noted that a proportion of patients receiving ibrutinib develop a significant peripheral lymphocytosis – 78 % in CLL patients59 and 34 % in MCL patients.54 The mechanisms underlying this may however be different in the two conditions: the lymphocytosis occurring in CLL has been correlated with a fall in tumour volume suggesting release of B cells from the lymph nodes59, while the lymphocytosis seen in MCL has been correlated with the degree of bone marrow involvement by disease, and has no association with changes in tumour volume.60

Inevitably the possibility of combining ibrutinib with other agents is being investigated. Currently trials are ongoing with ibrutinib in combination with R-CHOP, bendamustine + rituximab and rituximab alone, as well as with a host of other agents (see clinicaltrials.gov). Concern has arisen about combining BTK inhibitors with anti-cluster of differentiation 20 (CD20) antibodies as preclinical work has indicated that BTK inhibitors potentially modulate CD2061 and antagonise the cell-mediated effector mechanisms of rituximab (antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity).62,63 These concerns were dispelled by the results of a phase II trial of ibrutinib + rituximab showing an 87 % ORR, with 38 % of patients achieving CR.64 This CR rate is higher than that seen with either ibrutinib or rituximab when used as monotherapy (38 % and 34 %, respectively) suggesting a synergistic effect when the two agents are combined.

Of all the novel agents for MCL treatment this class currently shows the most promise and there are a plethora of new BTK inhibitors currently in development. The only published data is with ONO-4059, which shows promising activity in MCL in phase I trials.65 An important question is when in a patients management should BTK inhibitors be used, as there are data to suggest that patients with primary or secondary ibrutinib resistance appear to exhibit a more aggressive disease behaviour and salvage therapy is not very effective.66,67 This is not an issue when patients are receiving these drugs having exhausted conventional therapies; however, if similar problems are seen when the drug is used earlier on in the disease course we may have to be careful when it is used. The possibility of utilising these agents to enable a young patient with relapsed disease to undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantation is being explored with good anecdotal results.

New Anti-CD20 Antibodies

Building on the clinical success of rituximab, new anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies have been developed that either improve the direct cytotoxic effect of the antibody or enhance its interaction with effector mechanisms.

As with other NHL subtypes rituximab has now been shown to confer a survival benefit in MCL when administered with combination chemotherapy26,68–70 prompting investigations of whether these newer anti-CD20 antibodies would improve this further. Obinutuzumab is a humanised antibody that has been engineered to elicit higher direct cytotoxicity and antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Monotherapy with this drug in relapsed/refractory NHL with two dosing regimens was investigated in a phase II trial. Response rates were higher in those patients receiving higher doses (ORR 55 % in indolent patients; 32 % in aggressive disease) and similar response rates were also seen in patients who had been rituximab refractory.71 Interestingly a randomised trial between obinutuzumab and rituximab in relapsed indolent NHL (mostly non-mantle cell histology) showed a higher ORR and CR rate for obinutuzumab in the follicular lymphoma patients only, indicating that for some NHL subtypes it may be superior to rituximab.72

Ofatumumab is a fully human antibody that binds to a unique binding site on CD20 and harnesses increased complement dependent cytotoxicity compared with rituximab.73 Although this drug shows significant activity

in CLL74,75 the results of ofatumumab monotherapy for NHL have not been as impressive. A small phase II trial of monotherapy in relapsed/ refractory MCL showed an ORR of 8.3 %,76 which is similar to the 11 % ORR seen in a larger trial of rituximab-resistant follicular lymphoma.77 The efficacy of both ofatumumab and obinutuzumab are currently being investigated in combination with various chemotherapeutic agents in many NHL subtypes, including MCL.

Bendamustine

Bendamustine is a drug that demonstrates both alkylator and antimetabolite properties. Despite being used for many decades in Germany, its use has only relatively recently expanded and it has been demonstrated to have a potential role in the treatment of NHL.78,79 Based on single-agent activity, bendamustine has been combined with other agents displaying impressive results, including in MCL. A multicentre randomised trial of bendamustine with rituximab compared with R-CHOP as first-line therapy for indolent and MCL demonstrated a significantly longer PFS in the bendamustine arm (69.5 months versus 31.2 months). The bendamustine and rituximab also resulted in lower toxicity than R-CHOP.80 Similarly exciting results are seen in relapsed/refractory disease: the ORR for bendamustine plus rituximab in this setting is 92 % (59 % CR).81 The phase II trial of bendamustine with rituximab and bortezomib demonstrated an ORR of 71 %, although there was a high rate of adverse events with this combination.82 Further bendamustine containing multi-agent regimens are currently on trial.

Phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K) Pathway Inhibitors

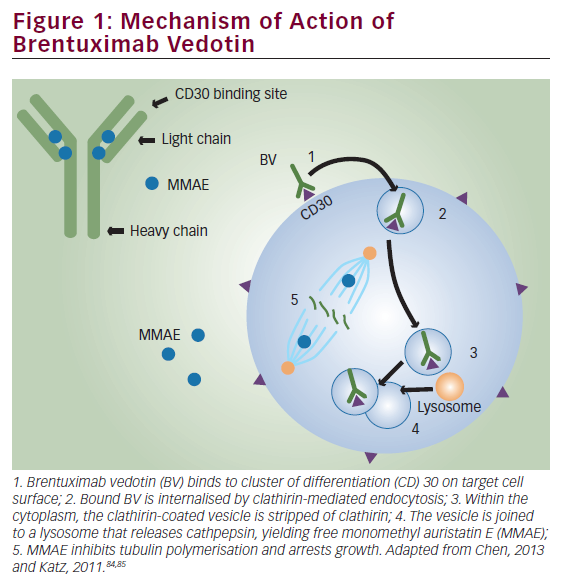

As in many other human cancers, the phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway is frequently dysregulated in MCL. The significance of this pathway in MCL pathogenesis is thought to be due to the importance of the serine-threonine kinase AKT in stabilising cyclin D1 mRNA and increasing its translation.83,84 There are four isoforms of PI3K, of which the P110δ isoform appears important in B cell development and signalling. Blocking this pathway therefore disrupts survival signals both intracellularly and from the tumour microenvironment, promoting cell survival.85,86

Idelalisib is a selective potent inhibitor of P110δ, which has shown preclinical activity in a range of haematological malignancies.86 In a phase I dose escalation study in MCL the observed ORR was 40 % with a median PFS of 3.7 months and a duration of response of 2.7 months for all dosing cohorts combined (50 mg to 350 mg).87 This is broadly similar to the ORRs seen with bortezomib, lenalidomide and temsirolimus, all of which are approved for the treatment of relapsed MCL. Importantly, in the same phase I study doses of idelalasib >150 mg twice daily had a higher ORR of 69 %, including two complete remissions. This study determined there is no significant benefit in either pharmacokinetics or lymph node responses with a dose higher than 150 mg twice daily. This has therefore been chosen as the dose for further use in MCL. Interestingly, the 1-year PFS was 22 % and those patients with longterm disease control tended to be patients who had received less prior therapy, with a clear difference between those who had received more than six prior treatment lines and those with fewer than six.

The toxicity profile of idelalasib differs from that of the BTK inhibitors with diarrhoea, nausea, pyrexia, fatigue and rashes being the most common adverse events seen. In particular, significant diarrhoea late in therapy as well as pneumonitis are toxicities that may lead to discontinuation of the drug. Notably, there was little haematological toxicity seen, suggesting that these agents may be suitable for combination therapies.

B Cell Lymphoma 2 (BCL2) Inhibitors

B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) acts by sequestering pro-apoptotic molecules rendering them inactive. Thereby shifting the balance away from proapoptosis to anti-apoptosis and promoting the survival of cancer cells. Many cancers, including MCL, exploit this mechanism of cell survival by overexpressing BCL2. The new class of BCL2 inhibitors has been developed to target this pathway and reduce BCL2 levels to release the sequestered pro-apoptotic molecules and initiate tumour apoptosis.88

Early attempts to inhibit the BCL2 family (obatoclax and AT- 101) demonstrated minimal clinical efficacy for haematological malignancies. The first drug in this class to show significant efficacy (ABT-737) was not suitable for oral administration and not further developed. Its analogue navitoclax however is orally bioavailable and selectively inhibits BCL2 and BCL-XL. As a key factor in platelet survival BCL-XL inhibition predictably results in dose-limiting thrombocytopenia rendering it difficult to administer this drug in doses with therapeutic efficacy.89 Re-engineering of the navitoclax molecule has resulted in the development of ABT-199, an orally bioavailable BCL2 homology 3 (BH3) mimetic that selectively inhibits BCL2. The potency of this drug is demonstrated by the ability of a single dose of the drug to induce fatal tumour lysis syndrome in CLL patients within 24 hours.90

Preclinical work with venetoclax (ABT-199) demonstrated significant delay in tumour growth in MCL-bearing mice and clinical data appear promising. Early results from the NHL arm of the phase I trial of venetoclax have shown a 53 % ORR (CR 8 %; PR 44 %). Within this heterogenous mix of NHL subtypes the drug appears most efficacious in MCL (82 % ORR) and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia (100 % ORR).91 Despite the numbers of patients in these subgroups being small, further trials are clearly warranted, especially as the drug is relatively well tolerated, with the most toxicities experienced being gastrointestinal, fatigue and mild haematological suppression.

As a disease with a high mutation rate, there is rationale for trying to target MCL cells with more than one of these novel agents. Preclinical work with a variety of MCL cell lines has shown a synergistic activity between ibrutinib and a number of other agents. An assortment of these combinations will shortly enter early clinical trials and may herald a new era in the management of this difficult disease.

Conclusions

While MCL remains incurable, the treatment options for patients with relapsed disease has increased significantly over the last few years. Many of these treatments are highly efficacious and are likely to impact on the OS of MCL patients. The initial use of these agents and careful monitoring will help answer further issues such as how the disease behaves after failure on these drugs, with the early indications being of a very poor prognosis after failure of BTK inhibitors. The question of whether there will be benefit in using these drugs sequentially or in combination remains to be seen; however, preclinical work is beginning to tease out some answers to this. The optimum place in the treatment algorithm for these new drugs is not yet clear. For older patients these agents may allow control of relapsed disease, following conventional chemotherapy. In younger patients there is the added option to potentially use these agents to achieve good remissions following relapse post autologous stem cell transplant in order to bridge the patient to allogeneic transplantation. This approach has been successful in our centre and central data is currently being collected about patients in whom this strategy has been employed worldwide. The very exciting prospect is of combinations of these novel targeted agents, which has the very real possibility of replacing conventional chemotherapy for this difficult disease.