The potential role of vinflunine in sequential treatment strategies for urothelial carcinoma, in both the perioperative setting and maintenance therapy, will be highlighted below.

Rationale for Perioperative Systematic Therapy in Bladder Cancer

The natural history and evolution of urothelial carcinoma suggests that the study of perioperative systemic therapy may yield benefits (see Table 1),1–9 because 20–50 % of patients experience distant recurrence, and 5–15 % have locoregional recurrence.

The gold standard for patients with muscle-infiltrating disease is cystectomy. However, when comparing cystectomy series, survival is strictly related to the invasion of the bladder wall (see Table 1). The probability of non-recurring and organ-confined disease is approximately 80–90 %, while in patients with extravesical invasion it drops to 60 % and to 30 % in patients with nodal involvement after cystectomy. These figures explain why perioperative chemotherapy is an attractive option. Based on good responses obtained in advanced disease, chemotherapy is shifting to the neoadjuvant setting.

Long-term results of radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasivebladder cancer were presented by Stein et al. in 1,054 patients. Increasing tumour stage and nodal involvement were associated with significantly higher recurrence rates and worse overall survival (OS) (p<0.001). Specifically, patients with extravesical disease or lymph node positive (LN+) disease had a higher risk of recurrence compared withpatients who had organ-confined disease. The 10-year OS for patients with extravesical bladder tumours was 27 %. In patients with LN+ disease the OS at 10 years was 23 %. Respective recurrence-free values were 47 % and 31 %.5 These data provide a strong biological rationale for perioperative systemic therapy in bladder cancer.

Neoadjuvant or Adjuvant Therapy in Invasive Bladder Cancer

Several unanswered questions arise when gauging perioperative treatment options and the timing of cystectomy in patients with invasive bladder cancer. For instance, should radical cystectomy be performed without delay or is neoadjuvant chemotherapy a valid strategy? Should cystectomy be performed regardless of chemotherapy? Should the bladder be preserved and cystectomy be delayed according to chemotherapeutic response? Should adjuvant chemotherapy be administered, and if so, which regimen would be the most suitable?

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Based on the encouraging results obtained with cisplatin combination chemotherapy regimens in patients with advanced, metastatic disease, use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been advocated to improve survival in patients with micrometastatic disease, and second,to preserve the bladder. It is thought that therapy may be better tolerated in patients upfront prior to cystectomy. On the other hand, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may make surgery more challenging and increase post-operative complications. A malignancy that is resistant to neoadjuvant chemotherapy may progress due to delay of surgery. Other disadvantages associated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy include difficulties in assessing response, and the fact that staging is based on clinical rather than pathological criteria. Benefits obtained in some studies are not reproducible. Only meta-analyses allowed to show a survival benefit ranging from 5 to 7 % (see Table 2).

Almost all neoadjuvant chemotherapy trials were negative, except for that conducted by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) in 317 patients,which compared methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) followed by cystectomy versus cystectomy alone. The median survival for patients treated with neoadjuvant MVAC was 77 months compared with 46 months in patients treated with cystectomy alone (p=0.06). Respective 5-year survival was 57 % versus 43 %. The results achieved borderline statistical significance due to a long accrual and follow-up period. Patients treated with surgery alone had a 33 % greater risk of death compared with those treated with combination therapy (hazard ration [HR]=1.33, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.00 to 1.76).8 These data strongly support the argument that neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy should be further investigated as an approach to optimise muscle-invasive bladder cancer treatment.

A subsequent retrospective analysis showed that patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and successful surgery, having had more than 10 lymph nodes removed, had a 5-year survival of 81 %, whereas patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy and had fewer than 10 lymph nodes removed had a 5-year survival of 39 %.15 Surgical factors, therefore, have a considerable impact on bladder cancer outcome, and many factors are determinant for survival (see Table 3). The quality of surgery cannot be underestimated.

The largest neoadjuvant chemotherapy randomised trial was performed in 976 patients with T2–T4 muscle-invasive N0 urothelial cancer.10 Patients were randomised to three cycles of cisplatin, methotrexate and vinblastine (CMV) versus no CMV, followed by either cystectomy or radiotherapy local treatment that was left to the investigator’s discretion. When first published in 1999,16 the data did not reach statistical significance, but at 7 years of follow-up, a 6 % survival difference in favour of patients treated with neoadjuvant CMV was reported, and the results reached borderline significance (HR=0.85, 95 % CI 0.72–1.00; p=0.048).11 With a longer follow-up of 10 years (median follow up of 8 years), the 6 % survival difference was maintained with neoadjuvant CMV (HR=0.84, 95 % CI 0.72–0.99; p=0.037).17

Meta-analyses have been performed, notably by the Advanced Bladder Cancer (ABC) collaboration group.18 Evaluation of 11 randomised neoadjuvant chemotherapy trials, including a total of 3,005 patients, showed that the subgroup of patients treated with a cisplatin-based combination could benefit from an approximately5 % absolute survival advantage at 5 years. One point of interest is the definition of the optimal endpoint of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Studies and experience show that patients who obtain a pathological complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy have a better outcome compared with patients who are not downstaged, or to patients with nodal involvement.19

The threshold for absolute difference in survival is a point of debate. A difference of 10 % has been proposed as a minimal threshold for success,17 which may arbitrarily obscure the benefit conferred by perioperative chemotherapy. Colon cancer literature has, for instance, shown that adjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated a survival improvement with smaller absolute survival differences.20 Another concern is that many patients are ineligible for cisplatin-based combination adjuvant chemotherapy. There is a concern that toxicity of neoadjuvant chemotherapy could delay surgery, although data from the Medical Research Council/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (MRC/EORTC) and SWOG studies suggest that this is not the case.8,17

Patients with small pT2 tumours can be cured with surgery alone, and it has been proposed that it may not be in their interest to receive neoadjuvant treatment. Survival data from the SWOG trial argue against this notion,8 as neoadjuvant chemotherapy-prolonged patient survival with clinical T2 tumours by 2.5 years compared with surgery alone. Furthermore, surgical clinical staging data have shown that lowrisk clinical T2 patients who can be spared chemotherapy cannot be accurately identified by urologists.21–23

It has also been argued that patients could receive adjuvant chemotherapy instead of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a similar survival benefit. Although plausible, in practice, a third of patients do not receive postoperative chemotherapy following cystectomy, mainly because of poor PS, complications related to surgery, psychological distress, age or patient refusal. Quality of life data would help address the question of whether neoadjuvant therapy may be preferable to adjuvant therapy.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

The perceived benefits and detriments of adjuvant chemotherapy have also been the centre of debate. The advantages of adjuvant chemotherapy include accurate pathological staging, which facilitates evaluation of patient risk. Chemotherapy can be avoided in low-risk patients, and overtreatment can thus be prevented. Finally, this practice avoids delaying definitive surgery. The main disadvantages are that no in vivo assessment of patients is available, and that many patients are less able to tolerate chemotherapy after surgery.

An ABC meta-analysis showed an absolute survival benefit of 9 % (HR=0.75, 95 % CI 1–16 %; p=0.019) at 3 years in patients who received cisplatin-based therapy, although these data are likely flawed by the poor quality of the trials included.24 Most adjuvant chemotherapy trials are underpowered, and have included fewer than 100 patients, complicating the drawing of definite conclusions. Data exploring adjuvant chemotherapy have shown that many patients are ineligible for cisplatinbased combination adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. Once again, the quality of received surgery is essential to optimise patient prognosis. Three recent trials have closed due to poor accrual. Data from a prospective meta-analysis of the EORTC individual patient data will be of interest.

How can Perioperative Chemotherapy Results be Improved?

Suggestions on how to improve outcomes of perioperative chemotherapy include the discovery and use of predictive factors of response, and the use of new drugs and targeted agents.

Based on retrospective studies suggesting that urothelial carcinoma patients with altered p53 had worse survival compared with patients who had wild-type p53, a randomised trial evaluating MVAC adjuvant chemotherapy was performed in these patients after cystectomy.25 Based on p53 status, 521 patients were randomised to receive MVAC for three cycles versus observation. The results of initial studies were not corroborated, and the predictive and prognostic value of p53 status was not confirmed.

The study and validation of predictive factors is likely to be among the most interesting fields in the development of new drugs, because tumour biopsies are available prior to chemotherapy. Studies can be performed before administering chemotherapy (e.g. genomics or proteomics). Following treatment and radical cystectomy, the mechanism of resistance can for instance be studied in patients with residual tumours who do not respond. pCR can be rapidly determined after surgery, or after three to four cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Given that pCR is a favourable prognostic factor correlating with long-term outcomes, the efficacy of a systemic regimen is evident early.

Vinflunine may be an interesting agent in this setting, because vinca alkaloids are active as single agents in bladder cancer, and they have been incorporated in most bladder cancer chemotherapy regimens (as vinblastine). A phase I/II study in 53 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) demonstrated that the combination of vinflunine with cisplatin was safe, with doses of 80 mg/m2 cisplatin and 320 mg/m2 vinflunine. Pharmacokinetic analyses showed no interactions between these two drugs.26 It may be helpful to develop a phase I/II feasibility trial of a dose-dense q3w (in order for patients to receive treatment on 1 day) neoadjuvant regimen with cisplatin plus vinflunine to see if it is tolerated in bladder cancer in the same way as in NSCLC, as bladder cancer patients are often more frail and perform worse than patients with other tumours.

There are thus two opportunities to incorporate vinflunine in new potential perioperative chemotherapy regimens. First, bladder cancer patients could be treated in the neoadjuvant setting with a combination of cisplatin and vinflunine. A phase II exploratory study would be interesting in this context, with inclusion of translational endpoints. The trial could, for example, be used to assess response rates and identify potential markers (akin to an in vivo chemosensitivity test), and then moved to a subsequent use of cisplatin plus vinflunine phase II randomised trial. Second, in patients who have been treated with a standard combination of cisplatin and gemcitabine, vinflunine could be used in patients who did not respond to treatment. These are situations for which the role of vinflunine has not been explored. The effect of vinflunine on the subsequent cystectomy and neobladder is for instance not known (e.g. hepatic and renal toxicity). However, MVAC neoadjuvant chemotherapy is currently used in all patients with muscle-infiltrating disease, so nephrotoxic and potentially hepatotoxic drugs are being delivered with no major complications. The trials outlined above demonstrate that noeadjuvant chemotherapy does not add toxicity to surgery. Over the last 10 years, the neoadjuvant therapy approach has become more popular, due to more convincing data. Resistance from both oncologists and urologists is receding. A recent survey in the US, however, reported that twice as many physicians administered adjuvant chemotherapy compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy.27 A phase III trial is planned in the neoadjuvant setting that is going to investigate cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus accelerated MVAC, with the objective of comparing regimens and collecting tissue samples to assess whether efficacy can be predicted. One of the caveats associated with performing this randomised trial is that both arms are experimental. Standard MVAC was initially planned, but accelerated MVAC was chosen because it is better tolerated and may be more active.28

Two-tiered Treatment Strategy in the Metastatic Setting

In the metastatic urothelial carcinoma setting, problems include the fact that it is an aggressive disease, which despite being chemosensible, has not been investigated in a large number of randomised controlled trials. Metastatic urothelial carcinoma affects an elderly population, and is associated with various comorbidities that include reduced renal function.

Von der Maase et al. compared GC versus MVAC in patients with locally advanced or metastatic TCCU (n=405). OS, time to progressive disease, time to treatment failure and response rate were similar in both arms. However, GC had a better safety and tolerability profile compared with MVAC,29 which is why most trials use GC as the preferred chemotherapy template for patients with locally advanced and metastatic TCCU. The median survival of GC or MVAC regimens is about 15 months, although outcomes demonstrate heterogeneity based on the number of prognostic factors (PS <80 % and visceral metastases).30,31

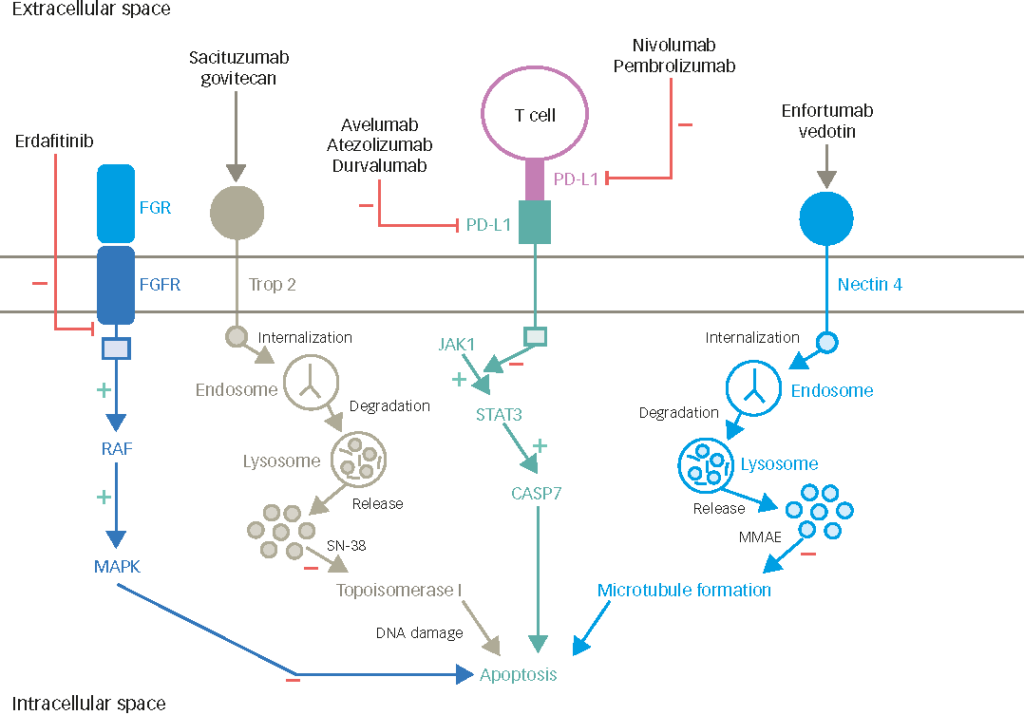

Over that last 20 years, treatment objectives in metastatic urothelial carcinoma have been to increase the number of CR and prolong response duration. The therapeutic strategies that have been adopted include evaluation of new combinations (e.g. triplets), sequential therapies, maintenance therapies, new drugs and molecular targeted therapies.

New Combinations

In investigations of new triplet combinations, the addition of paclitaxel to GC did not demonstrate a statistical improvement in survival of urothelial carcinoma, nor did dose-dense chemotherapy regimens (see Tables 4 and 5).32–37 Phase III randomised trials have not shown important improvements in OS when investigating regimens other than GC or MVAC (see Table 6).29,36,38–43

Thus, in the field of metastatic urothelial cancer treatment, a plateau has probably been reached, with little improvement in the last 10 years with doublet or triplet combinations. MVAC and GC regimens are firmly established as standard chemotherapies in the first-line setting, and vinflunine is the only approved drug for use after failure of a platinum-based regimen. The role of targeted therapies in the treatment of metastatic bladder cancer is still not known.

Sequential Therapies

Theoretical models suggest that sequential administration of chemotherapy may improve targeting of different cell populations within a tumour. Additionally, administration of two or three sequential drug combinations in high doses may overcome the toxicity associated with simultaneous administration of those agents. For instance, in a phase II trial conducted by Galsky et al., dose-dense doxorubicin plus gemcitabine followed by paclitaxel and carboplatin was given to 25 patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma and renal impairment.44 Overall response rate was 56% (including 35 % CR) (95 % CI 35–76 %), and median OS was 15 months (95 % CI, 11–30 months). Myelosuppression was the major toxicity, with 28 % G3/4 neutropenia. The 3-year survival was 25 %, and 28 % of patients were disease-free at 45 months. Dose-dense sequential chemotherapy was therefore tolerable and active in these patients. Prolonged disease-free survival was achieved in a subset of patients with primary unresectable disease or LN+ disease treated with carboplatin-based therapy with or without surgery.44

Another example of sequential therapy was developed by Milowsky et al., who combined sequential doxorubicin plus gemcitabine and ifosfamide, paclitaxel and cisplatin chemotherapy in 60 patients with metastatic or locally advanced TCCU. The study reported an impressive 73 % response rate (RR), but the population included 77 % of patients with local disease, 57 % with no risk factors and surgery was performed in 22 % of patients. The median OS was 16.4 months (95 % CI 14.0–22.5 months). Grade 3/4 neutropenia was observed in 68 % of patients. The authors concluded that the regimen was active but associated with elevated toxicity, which did not appear to be superior to non-sequential regimens.45

An additional rationale for sequential therapy is that different cell types are present in a given population of tumour cells,46 and clonal populations may develop when treated with a combination regimen. Administration of sequential therapy may slow the development of subclones.

Maintenance Therapy and Targeted Therapy

Based on vinflunine efficacy following failure of platinum-based chemotherapy,47–49 maintenance therapy with vinflunine could be of interest. With the knowledge that resistance occurs over time,50 the early use of non-cross-resistant treatment regimens could be interesting after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, because this approach may increase the probability of killing more cancer cells before the development of resistance.

Newer cytotoxic drugs and targeted therapies may be more effective than more traditional standard treatments. The former often have an improved tolerability profile, meaning that treatment can be extended for alonger period of time. Patients who have an objective response or disease stabilisation after initial chemotherapy may benefit from maintenance therapy when tumour burden is low. There are two methods of administering maintenance therapy. The first is continuation maintenance, which consists of using at least one of the agents given in the first-line setting line beyond four to six cycles, in the absence of disease progression. The second – probably more interesting – is switch maintenance, which involves the initiation of a different agent with a separate mechanism of action, not included as part of the first-line regimen, in the absence of disease progression, after four to six cycles of therapy.

Approved treatment algorithms for maintenance therapy have been developed in metastatic NSCLC. Whether to offer continuation maintenance, switch maintenance or a chemotherapy break to a patient who is responding after four cycles of first-line chemotherapy is a decision that must be made with the patient on an individual basis.51 Patients are only candidates for maintenance (switch or continuation) if they have had a tumour response or have stable disease after four to six cycles of chemotherapy. Observation is also an option.51

In NSCLC, as shown in a recent single-agent meta-analysis of 12 studies in a total of 4,286 patients,52 patients who had maintenance chemotherapy consistently performed better than patients who were followed by observation alone. Switch maintenance was also shown to be superior to continuation maintenance.52 On the strength of these maintenance data in NSCLC, two maintenance studies have been initiated in fit TCCU patients not progressing on cisplatin-based chemotherapy. The international JASIMA multicentre in 77 patients will evaluate vinflunine maintenance after four cycles of GC combination. The second maintenance study is the randomised phase II multicentre MAJA Spanish trial in patients (39 per arm) who will be randomised to receive vinflunine+BSC versus BSC alone after six cycles of GC (NCT01529411). The primary objectives of these studies is PFS. Maintenance trials ought to be designed to measure time to disease progression, for which a randomised design is essential. The MAJA trial is a randomised trial.

There may be concerns with patient heterogeneity, because eligible patients were allowed to receive four to six GC treatment cycles prior to randomisation. However, it is an exploratory trial that will help assess the toxicity of switching to a different drug with a separate mechanism of action, and whether maintenance therapy with vinflunine provides some benefit in terms of relapse.

Conclusion

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is an interesting potential approach in the development of new drugs, and may expedite the development of new agents. A feasibility study evaluating the combination of neoadjuvant cisplatin and vinflunine would be of interest in bladder cancer patients, and the inclusion of a translational component would add value to the analysis, in order to identify biomarkers. The study would naturally involve strict control of the primary tumour, because cystectomy will be delayed in participating subjects. Vinflunine may have a role as front-line neoadjuvant chemotherapy in combination with cisplatin or in non-responders after cystectomy. In addition to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, there is also a strong rationale for maintenance chemotherapy, and vinflunine may also play a role in this setting.