Ovarian cancer remains the leading cause of death from gynaecologic malignancies. Although endometrial cancer occurs more frequently, the vast majority of patients who develop this disease present with post-menopausal or other irregular bleeding problems and are usually diagnosed with early-stage disease and experience long survival. In contrast, the presenting signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer are non-specific and almost 75% of patients already have extensive abdominal disease at the time of diagnosis (stage IIIC and IV). The failure to be able to detect ovarian cancer at earlier stages has led to it being labelled ‘the silent killer’.

The use of extensive debulking procedures, which may include resections of the gastrointestinal (GI) or urinary tracts, can decrease the tumour burden for cytotoxic chemotherapy and help to prolong survival. The addition of taxanes to platinum-based therapy have led to significant improvement in both progression-free and overall survival in patients with either optimally reduced or sub-optimally reduced advanced-stage disease.

Currently, ovarian cancer patients are living longer and as the disease tends to remain within the peritoneal cavity without affecting vital organs, patients may maintain a good performance status for a long time. Unfortunately, disease usually relapses. Relapse may be heralded by elevation of CA-125 and eventually symptoms and evidence of disease will appear, leading to treatment of recurrent disease. With patients living longer and receiving therapy for longer periods of time, there is a need for agents that are well tolerated, lacking of cumulative toxicity and able to maintain quality of life rather than worsen it due to unintended side effects.

Treatment at time of relapse has been guided by the interval from the patients’ prior platinum exposure. Those patients who had demonstrated progression of disease while on platinum-based therapy, or relapsed within six months from their last platinum therapy, were thought to be platinum-resistant and should be treated with other non-cross-resistant agents. Patients who had initially responded and demonstrated clinical progression more than six months after their last platinum therapy were thought to have potentially platinum-sensitive disease and would be re-treated with platinum agents.

The probability of responding to re-treatment increases with time from the last platinum exposure. After a platinum-free interval of two years, response rates may approach 60%, which is similar to initial response rates in untreated disease. Although response rates at earlier intervals were lower, prior to the late 1990s there were no agents that were thought to have significant activity in relapsed ovarian cancer and platinum-based therapy was the standard.

Paclitaxel did exhibit activity in recurrent ovarian cancer but, based on several studies, quickly moved into first-line therapy as part of a taxane and platinum-based combination. Then, several agents in phase II trials showed promising activity in relapsed ovarian cancer. A phase III trial, comparing topotecan with paclitaxel, showed statistically equivalent response rates and survival data in paclitaxel naïve patients. Based largely on this data, topotecan was approved for use in relapsed ovarian cancer by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Phase II trials with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) that had been underway had shown activity for PLD in platinum refractory ovarian cancer. It was then decided to proceed with a phase III trial comparing PLD with topotecan.

The results of this phase III trial were initially reported in 2001. There were 474 patients enrolled from 104 sites from around the world. Patients were stratified upon enrollment based on platinum sensitivity or resistance and on the presence or absence of bulky disease. There was no difference in response rates in the overall or any subgroup analysis. In the survival data that were available, there was no difference in progression-free or overall survival for the entire group. However, there was a significant improvement in progression-free survival and an even greater improvement in overall survival for the platinum sensitive patients initially treated with PLD. There was a large number of censored events as many of the patients had not progressed or died at the time of the report. After more than 90% of the patients had recurred or died, a planned updated analysis was performed to re-evaluate the survival data.

With long-term follow-up, overall survival for all patients now showed a statistically significant improvement for initial therapy with PLD. Although the median survivals were similar at 63 weeks for PLD versus 60 weeks for topotecan, there was an 18% risk reduction in death for all patients that was significant, with p=0.032. There were still no significant differences in the patients with platinum-resistant disease. However, in the platinum-sensitive group, patients initially treated with PLD did significantly better. The median survival was 27 months for initial treatment with PLD versus 17.5 months for initial treatment with topotecan. Overall, there was a 30% risk reduction in death for initial treatment with PLD that was significant at p=0.017.

What does this mean for patients with platinum refractory disease? Currently, there are three randomised phase III trials of single agents in platinum-resistant disease. All agents have shown similar activity whether measured by response or survival data. No single agent has been shown to be superior to another; therefore, in patients with platinum-refractory disease, the choice of agent should be based on toxicity and quality of life criteria. The lack of alopecia, minimal nausea/ vomiting, minimal myelosuppression and ease of administration, with a lack of cumulative toxicity, would favour PLD as an initial choice for many patients with platinum-refractory disease. Some authors have shown activity for the combination of gemcitabene and cisplatinum in patients with resistant disease; however, there is significant toxicity with this regimen and a randomised comparison has not been performed.

In patients with platinum-sensitive disease, several phase III trials have compared non-platinum agents; however, there are no available data comparing platinum with a non-platinum agent in platinum-sensitive disease. Response rates for all agents in all the randomised trials are about 30%, which is similar to the response rates reported for platinum re-treatment in the 12- to 24-month platinum-free interval. In view of the prolonged progression-free and overall survival seen with PLD relative to topotecan, response rates may not be the best measure of activity in this group of patients. It is still not possible to compare a non-platinum agent with a platinum analogue; however, based on the improved progression-free and overall survival with PLD, this should be the first choice of the non-platinum agents.

Recently, two randomised trials have compared single-agent carboplatin with carboplatin combination in platinum-sensitive patients. ICON 4 used paclitaxel as the second agent and demonstrated significantly improved response rates, progression-free survival and overall survival in the patients receiving the combination. The AGO-GCIC trial used gemcitabene as the second agent in the combination. While the combination again showed a significantly better response rate and progression-free survival, there was no difference in overall survival.

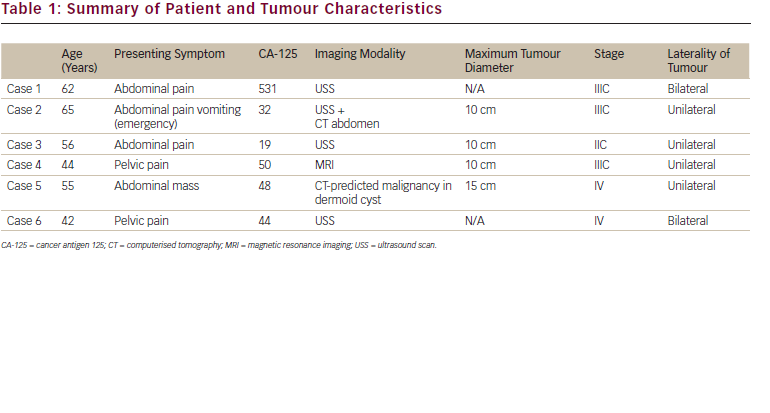

Does this mean that all patients with platinum-sensitive disease should be retreated with combination platinum-based therapy? Although all of these trials were randomised, there are significant demographic differences that may explain some of the apparent differences in the study results (see Table 1).

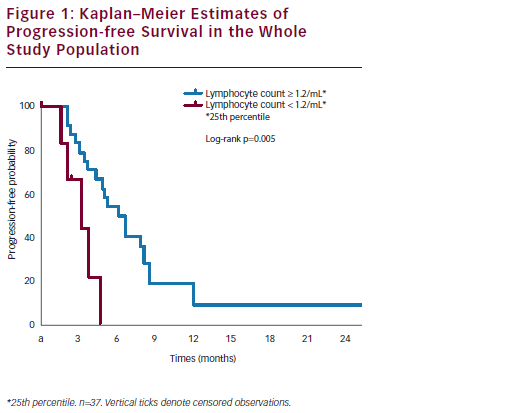

The ICON 4 study had a greater number of patients who relapsed after 12 months relative to the AGO-GCIC trial, which in turn was greater than that in the trial of PLD versus topotecan. A similar pattern was seen when looking at the number of patients who had not received prior taxane in each study. A single agent would certainly be expected to have a lower response rate than a combination; however, the two-year survival with single agent PLD was similar to that of the platinum–taxane combination in ICON 4 and the median survival was equivalent to the combination (see Figure 1). The response rate of single-agent PLD was equivalent to that of single-agent carboplatin in the AGO trial (see Figure 2). The progression-free survival was superior to single-agent carboplatin and similar to the gemcitabene combination and the median overall survival of single-agent PLD was superior to either arm of the AGO trial.

Those patients who have a prolonged platinum-free interval, will probably have a better progression-free and possibly overall survival with combination therapy; however, for those patients with early platinum-sensitive relapse, i.e. six to 12 months, the data does not clearly indicate an advantage for platinum-based therapy at this time.

In summary, no agent or combination has shown any significant improvement by any measure in platinum-resistant disease. The ease of administration and low toxicity profile would favour the use of PLD as the agent of choice in platinum-resistant disease. PLD is the only non-platinum agent to demonstrate a progression-free and overall survival advantage in platinum-sensitive disease and should be the first choice whenever resorting to a non-platinum agent.

Although combination therapy has shown improvement on response rates and progression-free survival in platinum-sensitive patients, it is not clear at this time that equivalent results might not be achieved with sequential single-agent therapy, without the added toxicity. ■

Long-term Survival Advantage for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer Patients Receiving Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin

Article

Further Resources

Trending Topic

Worldwide, ovarian cancer is the seventh most common cancer and the eighth most common cause of cancer death in women.1 The GLOBOCAN study estimated there were 239,000 new cases in 2012 and 152,000 deaths due to this disease. There are nearly 600,000 women living within 5 years of an ovarian cancer diagnosis.1 In the EU, age-adjusted ovarian […]

Related Content in Ovarian Cancer

Gynecological malignancies can be difficult to treat. Ovarian cancer carries with it the worst prognosis of all gynecological cancers. Approximately 75% of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced disease which is curable only in a minority of cases, ...

It is not by chance that this issue of European Oncology & Haematology is opened by an editorial from Suhag, dedicated to the oncological scenario in developing countries, warning that there is “little light at the end of the tunnel”. ...

Areader of 20 years ago could have hardly imagined many of the contents of this issue of European Oncology & Haematology. Twenty years ago, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) was still treated with hydroxyurea, interferon and allogeneic stem cell transplantation, and multiple ...

Epithelial ovarian cancer has long been recognized as being highly sensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy, with anticipated objective response to platinum-based chemotherapy of approximately 70-85%1. Furthermore, overall survival (OS) for women presenting with advanced disease has been documented to have improved ...

Mature cystic teratomas (also called dermoid cysts) account for about 30–45 % of all ovarian neoplasms and around 60 % of all benign tumours arising in the ovary.1 Malignant transformation of the various mature tissue components of a dermoid cyst is rare and the ...

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most lethal gynaecological cancer. In 2010, approximately 21,880 new cases and 13,850 deaths occurred in the US,1 while in the EU in 2004 the incidence of newly diagnosed cases was 42,700 with a mortality of 12/100,000 women/year.2 The current treatment ...

Axel Heidenreich is Chairman and Director of the Department of Urology at University Hospital, Aachen, Germany, whose main area of interest is prostate cancer. His recent scientific awards include the Paul-Mellin-Preis der Nordrhein Westfälischen Gesellschaft für Urologie (2010), the ...

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynaecological cancer. In the US, approximately 21,880 new cases were identified and 13,850 women died of the disease in 2010.1 In the European Union, the number of newly diagnosed cases was 42,700 in 2004 and the mortality rate is 12 ...

This issue of European Oncology highlights many of the challenges that we face in our fight against cancer in this diverse world. Clinical drug development has become complex, and independent academic research is in danger. Fortunately, these difficulties are not ...

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most common malignancy in women. In the US, approximately 22,000 new cases occur each year.1 In Germany, about 8,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. About 80% of patients suffer from advanced-stage disease (International Federation of Gynaecology and ...

Phenoxodiol ([2H-1-Benzopyran-7-ol, 3-(4-hydrophyphenyl] (PXD) is a synthetic derivative of genistein, a naturally occurring plant isoflavone. In the 1980s, genistein was discovered to have modest anticancer activity, and alterations in its structure created PXD and increased its anticancer ...

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most common malignancy in women. In the US, approximately 22,000 new cases occur each year.1 In Germany, about 8,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. About 80% of patients suffer from advanced-stage disease (International Federation of Gynaecology andObstetrics [...

Latest articles videos and clinical updates - straight to your inbox

Log into your Touch Account

Earn and track your CME credits on the go, save articles for later, and follow the latest congress coverage.

Register now for FREE Access

Register for free to hear about the latest expert-led education, peer-reviewed articles, conference highlights, and innovative CME activities.

Sign up with an Email

Or use a Social Account.

This Functionality is for

Members Only

Explore the latest in medical education and stay current in your field. Create a free account to track your learning.