Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a severe complication of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Most of the PTLDs originate from B-cells. Overall, 60–80% of PTLDs are associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV); this can vary depending on PTLD type and time of onset after HSCT.1,2 The majority of the general population is infected by EBV during their life, but an immunocompetent host mounts a swift immune response that controls proliferation of EBV infected B-cells. EBV then resides only in resting memory B-cells in latent form.3 The balance between latently infected B-cells and immune surveillance is disrupted after a patient receives HSCT. An increase in the number of infected B-cells (almost always of donor origin) may develop into PTLD.4–6

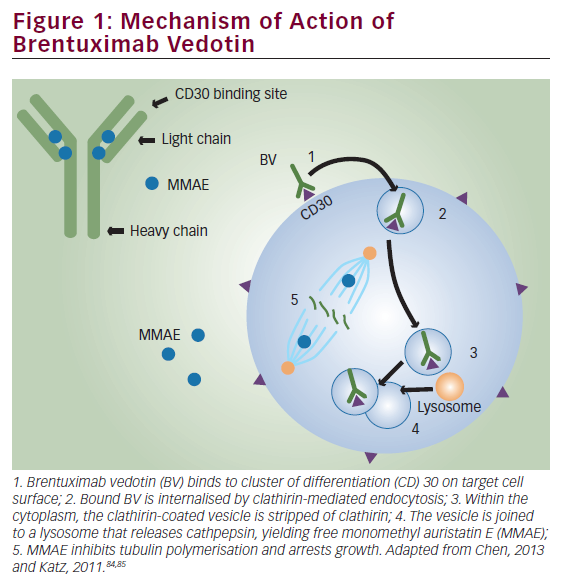

PTLDs are divided into three stages of evolution: early lesions, polymorphic PTLDs and monomorphic PTLDs. Monomorphic PTLDs are mostly derived from B-cells, but can also be of T-cell origin, and resemble aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas.5 PTLD resembling diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common.7 Rituximab, an anti CD20 monoclonal antibody, can be used effectively to treat them.8,9 Other types of PTLD are rare and only 4% of them show plasma cell differentiation.7,10 We would therefore like to present our patient with PTLD of duodenum with plasma cell differentiation.

Case report

A 43-year-old Caucasian female was diagnosed with MLL/PTD- and FLT3/ITD-positive acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) in June 2013. She was given “3+7” induction chemotherapy regimen (cytarabine 100 mg/m2 for 7 days and daunorubicin 90 mg/m2 for 3 days) followed by consolidation chemotherapy high-dose cytarabine (HiDAC) in July 2013. She achieved complete remission (CR) with negative minimal residual disease (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] for MLL/PTD gene). She underwent allogeneic HSCT with 10/10 sibling donor (sister) in September 2013, using a conditioning regimen of busulfan 3.2 mg/kg for 4 days, fludarabine 30 mg/m2 for 5 days and rabbit derived anti-thymocyte globulin (r-ATG [Thymoglobulin; Sanofi, Paris, France]) 3 mg/kg for 1 day, with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil as immunosuppression. She remained in CR for 14 months but relapsed in November 2014. She was then given Flag-Ida chemotherapy (fludarabine 30 mg/m2 for 5 days, cytarabine 2 g/m2 for 5 days and idarubicin 12 mg/m2 for 3 days) and again achieved CR. Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) was administered (5×105 CD3+ cells/ kg in December 2014 and 1×106CD3+ cells/kg in April 2015). Despite this, the disease relapsed (molecular relapse) in August 2015. The patient received one cycle of low dose cytarabine while waiting for a suitable unrelated donor. Through September and October 2015 sequential stem cell transplantation was performed (HiDAC chemotherapy and then conditioning with treosulfan 12 mg/kg for 3 days, fludarabine 30 mg/m2 for 6 days and r-ATG [Thymoglobulin] 3 mg/kg for 2 days) with 9/10 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatched unrelated male donor (DQB1 mismatch).

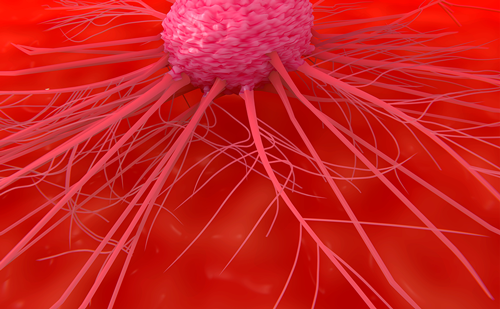

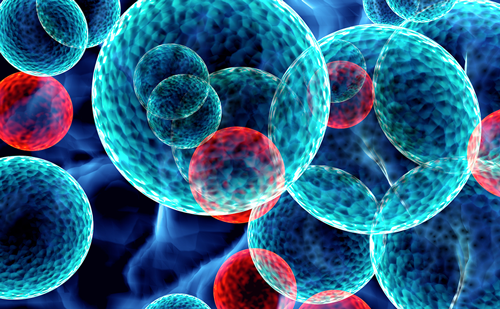

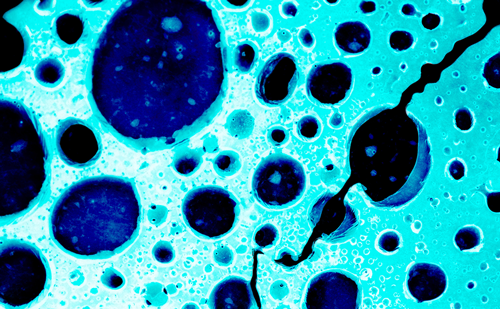

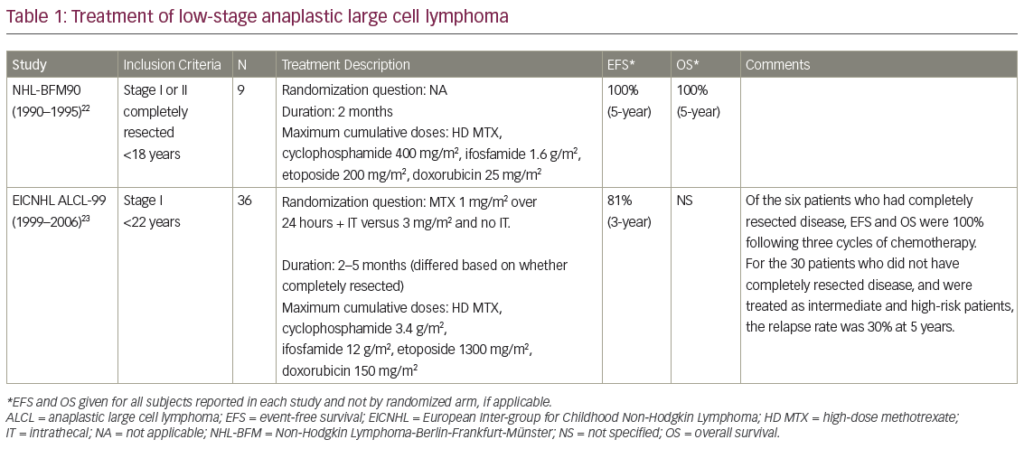

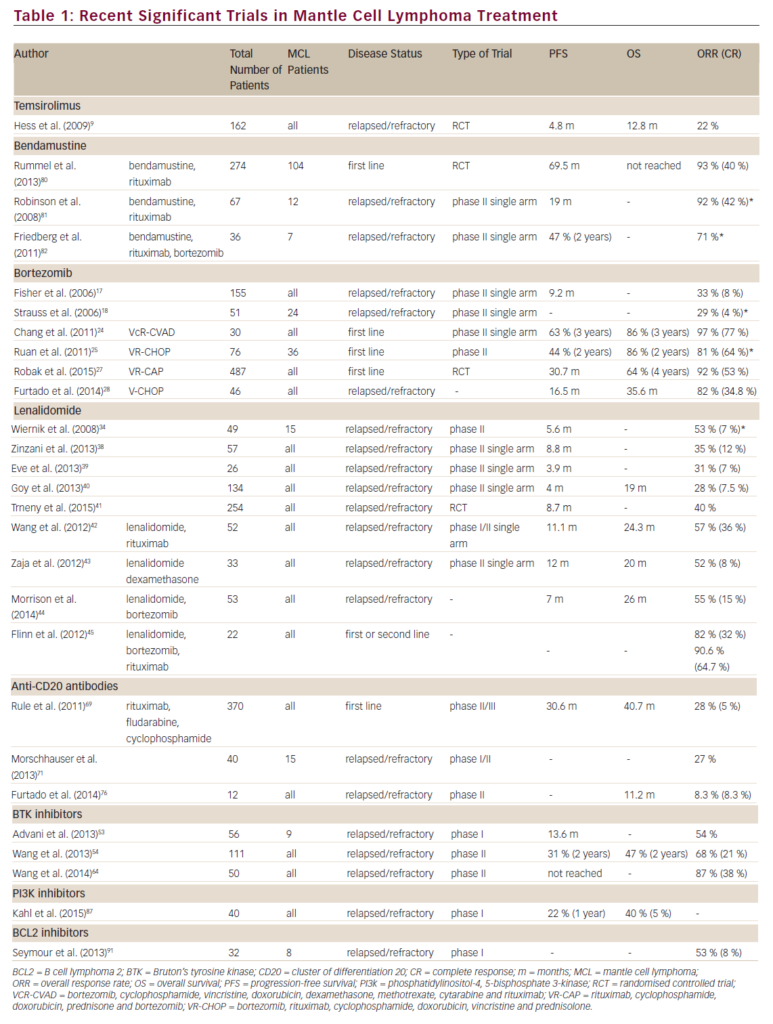

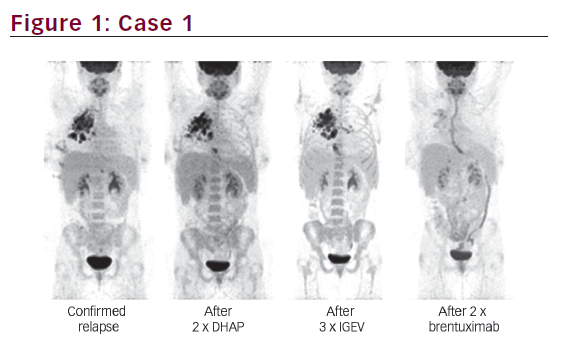

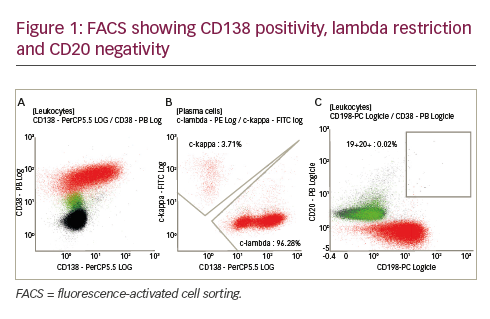

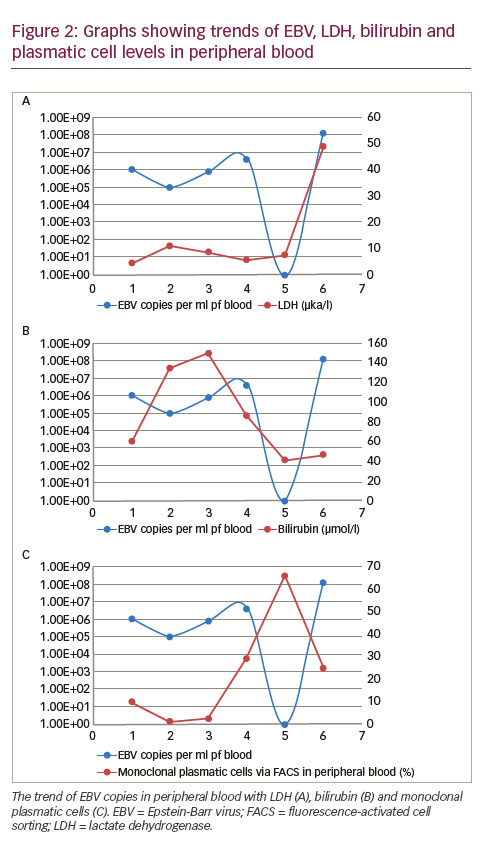

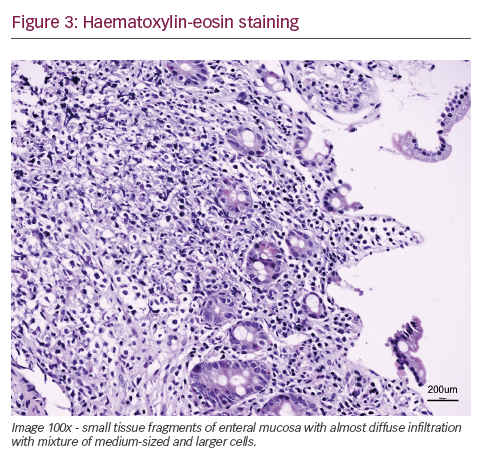

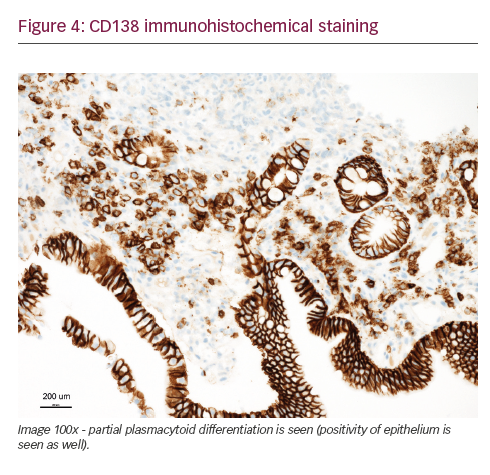

She was admitted on 14 December 2015 (day 66 after her second HSCT) for high fever, nausea and vomiting. The patient was given empirical treatment with meropenem. She showed no significant findings upon physical examination, on chest computed tomography (CT) scan, nor on abdominal ultrasound. Including normal liver, spleen and lymph nodes. No source of sepsis was found. Bone marrow aspirate confirmed remission of AML. Her EBV blood level was rising (1.1×106 copies/ml). Peripheral blood fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) showed 10% of monoclonal plasma cells (Figure 1). EBV PTLD was then diagnosed. The patient received rituximab (375 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, 22) as the first line of treatment on days 67 and 74. Her EBV blood level decreased, but only temporarily (Figure 2). On day 74 the patient’s condition worsened and she presented with melena. Gastroduodenoscopy with gastric and duodenal biopsy was performed. Duodenal biopsy showed EBV-positive PTLD (plasma cells, lambda light chain restricted, CD138 positive, most of them EBV positive using Epstein-Barr encoding region [EBER] in situ hybridisation [Figures 3 and 4]). The patient also presented with paraproteinaemia (6.6 g/l) and elevated lambda free light chains (1,038 mg/l) on day 70. Five days later she developed severe sepsis with renal impairment. Antibiotic therapy was escalated (linezolid) and renal replacement therapy was started. On day 87 the PTLD rapidly progressed: 29% monoclonal plasma cells in her blood via FACS, 4.35×106 EBV copies/ml and further elevation of paraproteinaemia (9.2 g/l) was present. The failing rituximab monotherapy was replaced by the second-line treatment (rituximab 375 mg/m2 for 1 day, cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 for 1 day and methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg for 5 days).11 Her condition temporarily improved with disappearance of sepsis signs so antibiotic therapy was deescalated. On day 92 the patient was again septic with severe diarrhoea. Broad spectrum antibiotics were again administered (meropenem, linezolid, amikacin). The EBV blood levels were again rising rapidly (Figure 1). CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) was given as the third line of therapy on day 101. Despite all the treatment, the patient went into septic shock and died on 19 January, day 102.

Discussion

PTLD is a heterogeneous group of diseases and there are no strict guidelines for therapeutic approach. One of the options is reduction of immune suppression (RI) but it only occasionally results in CR, and is mostly effective for early lesions.7 Rituximab can be used as the first line of therapy for most of the newly diagnosed polymorphic and monomorphic PTLDs and plays a prominent role in treatment. Several studies strongly suggest that early introduction of rituximab-based therapy significantly improves overall survival.9 Evens et al. performed a multicentre analysis of 80 patients with PTLD after solid organ transplant. A 3-year progressionfree survival and overall survival for patients who received firstline

rituximab-based therapy were 70% and 73%, compared with 21% and 33% among patients who did not receive it as a component of initial therapy.12

Also, rituximab is relatively safe with few side effects (especially compared to chemotherapy).6 Other options involve CHOP-like chemotherapy.7

Our patient had PTLD with plasma cell differentiation, which is a rare type of PTLD. Karuturi et al. performed a retrospective analysis of 210 adult, solid-organ transplant, PTLD patients and only nine (4%) had PTLD with plasma cell differentiation. All their patients presented with extranodal involvement and laboratory tests included elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), beta-2-microglobulin, present paraprotein and EBV-positive tumour. CD138 positivity and a CD20 negativity is characteristic for PTLD with plasma cell differentiation. Radiotherapy, resection, and RI appeared to have at least some effect in these patients.10 Trappe et al. performed a prospective study from 2006 to 2010 of patients diagnosed with plasmacytoma-like monomorphic PTLD after solid organ transplantation. One hundred and eighty-two patients were reported to the German registry in those years and only eight (4%) had a diagnosis of monomorphic plasmacytoma-like PTLD. The cell population showed either lambda (two of eight patients) or kappa (six of eight patients) light chain restriction, and CD138 positivity (eight of eight), while CD20 was negative in all, and CD56 in seven of eight cases. Out of the six patients who received a RI as a first line of therapy two responded, and four patients showed progressive disease. The three patients with disseminated and progressive disease after RI, received systemic chemotherapy analogous to therapy of multiple myeloma. All three responded to treatment including one CR after chemotherapy consisting of bortezomib, doxorubicin and dexamethasone. One patient eventually died from disease progression. None of the patients received rituximab, as staining for CD20 was negative in all cases.7

Our patient’s plasmatic cells were CD138 positive, CD20 negative, CD56 negative and showed lambda light chain restriction (Figure 2). The patient presented with LDH elevation and elevated EBV levels in blood. Elevated bilirubin levels correlated with activity of PTLD (Figure 1). Despite being CD20 negative the rituximab therapy was capable of reducing an amount of EBV blood levels and number of monoclonal plasma cells in blood, if only temporarily (Figure 1). As a second line of therapy the patient was given combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone, a regimen used by Gross for patients who failed in first-line therapy for PTLD after solid-organ transplant. Overall, a response rate of 83% and CR of 75% was achieved in 36 patients.11 Our patient’s EBV copies in blood temporarily lowered. But even this regimen helped only for a short period of time.

This example and another studies show beyond doubt that rituximab improved clinical outcome of many patients with PTLD, but it still remains ineffective for many patients. And plasmacytoma-like PTLD can be one of the examples. Other possibilities for treatment like EBV-specific cytotoxic represent promising strategies in improvement of survival of patients with PTLD.5 Whether we should use treatment similar to treatment for multiple myeloma (like proteasome inhibitors) to patients with plasmacytoma-like PTLD remains unclear and should be investigated.