Antibody-based therapeutics have become an essential component of cancer therapy since the introduction of rituximab in the late 1990s. However, although they can confer clinical benefits, especially when combined with chemotherapy, many monoclonal antibodies do not provide long-term beneficial effects.1 There is therefore a need to improve the therapeutic efficiency of monoclonal antibodies. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) allow the linking of potent cytotoxic drugs to tumour antigen-specific antibodies, enabling specific targeting of drugs to neoplastic cells while minimising systemic toxicity. ADCs are becoming an increasingly important subclass of antibody-based therapeutics, with 35 ADCs in clinical development in November 2013.2

Cluster of differentiation (CD) 30 is a transmembrane cytokine receptor protein expressed on certain neoplasms but not normal cells, making it a promising target for therapeutic intervention. Two aggressive lymphoid neoplasms are characterised by strong and uniform expression of CD30: Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (sALCL). Early studies of anti-CD30 monoclonal antibodies were promising, although the antibodies had only modest activity as single-agent therapy,3,4 leading to the development of the anti-CD30 ADC, brentuximab vedotin (BV, Adcetris®).This review will focus on the unmet needs in the management of HL and sALCL and discuss clinical studies investigating the efficacy and safety of BV.

Current Standard of Care in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and Systemic Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

HL is characterised by the orderly spread of disease from one lymph node to the other. Systemic symptoms are associated with advanced disease. The incidence of HL shows a bimodal age distribution, with the first peak in incidence rates in young adults, and the second peak in older people.5 It is the most common malignancy in adolescents.6

Despite the fact that first-line combined chemotherapy regimens, including doxorubicin (Adriamycin), bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD), achieve durable remission rates in approximately 80 % of cases,7 a substantial proportion of patients with advanced HL (20–30 %) are refractory to therapy or relapse after initial treatment.8 Remission rates can be increased by around 10 % with the use of more intensive chemotherapy regimens such as bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone (BEACOPP), but this treatment carries the risk of serious adverse events (AEs).9,10

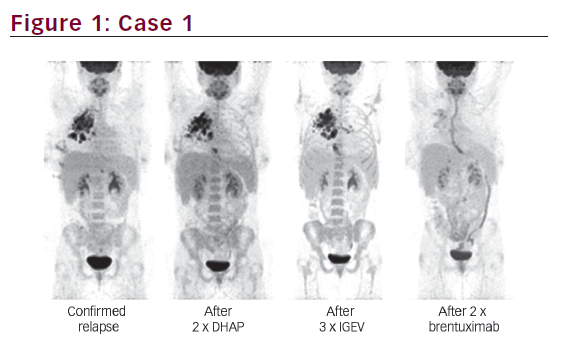

Relapsed or refractory HL can be treated by salvage chemotherapy based upon either ifosfamide (with carboplatin and etoposide [ICE] or etoposide and epirubicin [IVE]), gemcitabine (with dexamethasone and cisplatin [GDP] or with vinorelbine and doxorubicin [GND]) or platinum (with dexamethasone and cytarabine [DHAP] or etoposide, methylprednisolone and cytarabine [ESHAP]) and, if chemosensitive, are subsequently treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT), which has a 5-year time-totreatment failure (TTF) and overall survival (OS) of around 50 %.11–14 Normalisation of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) imaging prior to ASCT has been associated with improved outcomes.15 For patients who experience relapse after auto-SCT, the prognosis is poor: median survival time is approximately 2 years.11 Until recently, there has been no standard of care for patients with relapsed/ refractory HL after failure of auto-SCT. Options include palliative chemotherapy or reduced-intensity allogeneic SCT (allo-SCT). The use of allo-SCT is controversial, with disease relapse and progression reported in more than half of patients.16–18 Following the failure of allo- SCT, treatment options are limited and the prognosis for patients at this stage is extremely poor.19 There is therefore a need for new therapeutic options for HL patients with relapsed/refractory disease.

sALCL is a rare type of non-HL (NHL), and represents a group of large cell lymphomas, distinguished from other lymphomas by its anaplastic cytology and constant membrane expression of the CD30 antigen.20 It is a T-cell lymphoma comprising about 3 to 8 % of all NHLs in adults and 10 to 15 % of all NHLs in children.21,22 There are two subtypes of sALCL: primary systemic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)+ ALCL and primary systemic ALK− ALCL.20 Primary cutaneous ALCL also exists, but this is a separate disease entity and is localised to the skin.

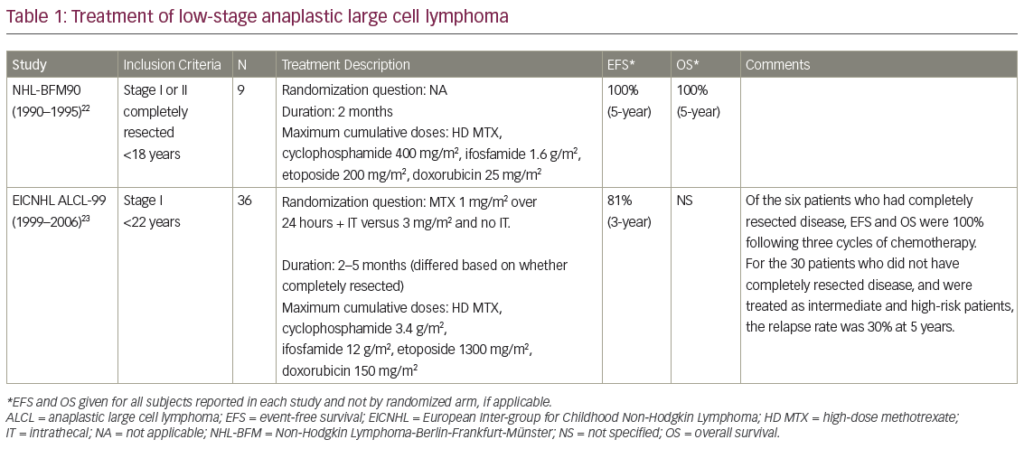

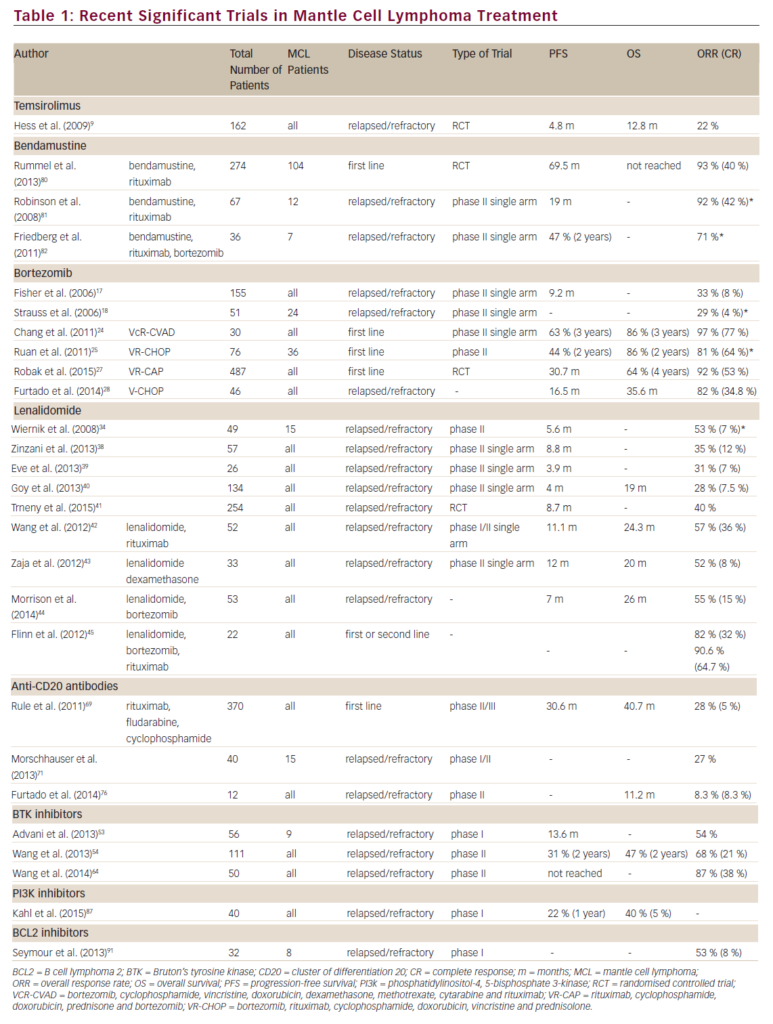

First-line therapy for sALCL is typically a combined chemotherapy regimen such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP). Overall responses of 86 % and 68 % have been reported in ALK+ and ALK- ALCL, respectively.23 ALK+ ALCL predominantly affects young male patients and responds well to chemotherapy.24 sALCL in paediatric and adolescent patients has a relapse rate of 25–30 %. ALK- ALCL occurs in older patients, affecting both genders equally and is associated with low response rates to chemotherapy: up to 60 % of patients may relapse after first-line therapy.20 The therapies for refractory or relapsed disease are highly variable, ranging from single-agent chemotherapy to allo-SCT, with some success, but no established standard. An oral ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitor is in early-stage clinical development,25 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFR) blockade with imatinib has also been effective in single cases.26

However, until recently, there was no standard of care for these patients with HL and sALCL. Given the young age of many patients, the management of these lymphomas represents an important unmet clinical need.

Anti-CD30 Antibody–Drug Conjugates – Brentuximab Vedotin

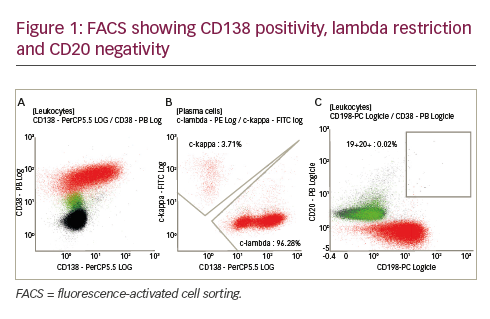

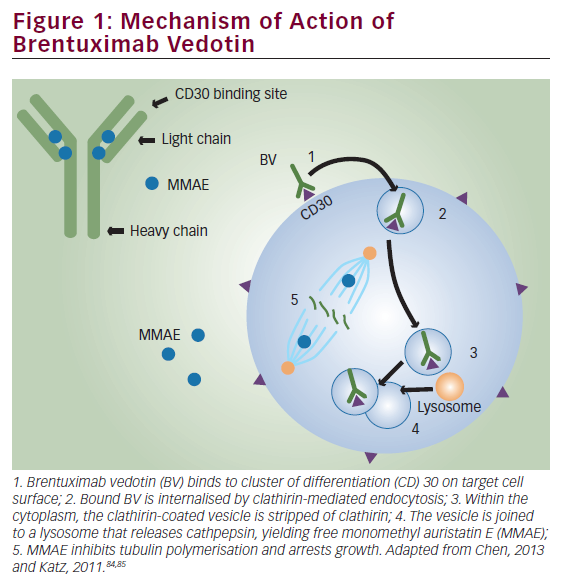

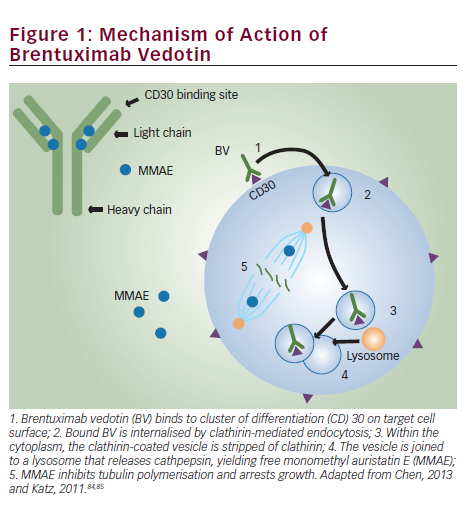

Brentuximab vedotin is an ADC composed of the monoclonal antibody cAC10, which targets the CD30 antigen on HL and sALCL cells; a highly stable valine-citrulline linker; and a potent antimitotic agent: monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), connected by a protease-cleavable valine-citrulline dipeptide linker. Its mechanism of action is illustrated in Figure 1. Binding of the ADC to CD30 on the cell surface leads to internalisation of the CD30-ADC, the result of clathrin-mediated uptake. Once inside the cytoplasm, the vessel joins to a lysosomal vesicle containing proteolytic enzymes, which then releases MMAE into the tumour microenvironment.27 The free MMAE blocks the polymerisation of tubulin, resulting in G2/M phase growth arrest and apoptotic death.28 In addition, MMAE accumulates in the extracellular space due to its membrane permeability and has potential cytotoxic effects on surrounding CD30-negative bystander cells.29

In addition to its effect on MMAE activity, treatment with BV induces the release of cytokines such as interleukin-6, chemokine ligand 17 and tumour necrosis factor α.30 Another potential mechanism of action is interruption of CD30/CD30 ligand interaction. The CD30 ligand (CD153) present on bystander cells may regulate tumour cell proliferation.31 By interfering with this interaction, BV may inhibit tumour growth. Treatment with BV may also focus the HL-specific immune response against the tumour as a result of the release of tumour antigens and proinflammatory modulation of the tumour microenvironment.32

Clinical Studies Investigating the Efficacy of Brentuximab Vedotin in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and Systemic Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma in Different Clinical Settings Relapsed/Refractory Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and Systemic Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

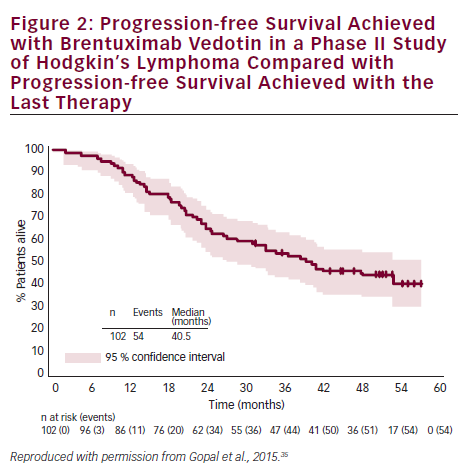

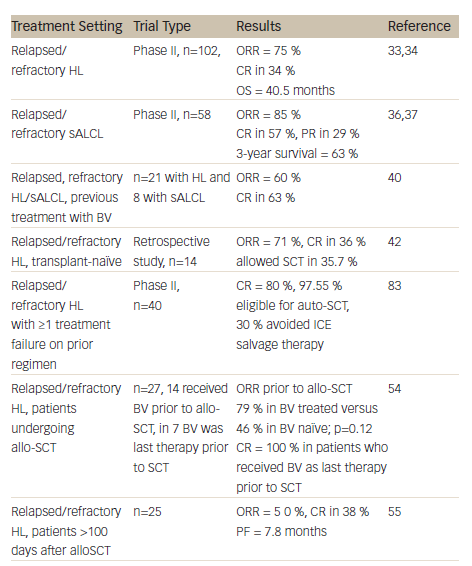

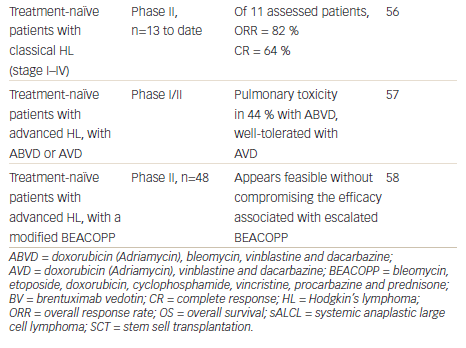

A summary of clinical studies investigating the efficacy and safety of BV in HL and sALCL can be found in Table 1. Two pivotal phase II studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of BV in relapsed/refractory HL and sALCL. In a phase II study of BV in patients with relapsed/refractory HL (n=102), the overall response rate (ORR) was 75 % with complete remission (CR) in 34 % of patients.33 In 3-year follow-up data, patients achieved a median OS of 40.5 months with BV (see Figure 2). Overall, patients received a median of nine cycles (range 1–16) and patients who achieved an objective response received more cycles of therapy.34 Recent follow-up data show that 47 % of patients who achieved CR on BV remain progression-free after a median 53 months. Younger age, less functional impairment and lower disease burden at baseline were associated with CR and longer survival.35

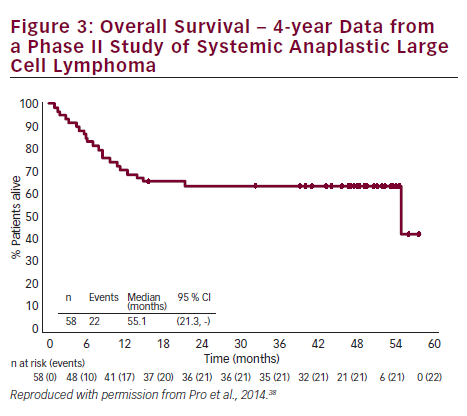

In a phase II study of BV in patients (n=58) with relapsed/refractory sALCL, the ORR was 86 %, CR in 57 % and partial remission (PR) in 29 %.36 At 3-year follow-up, the median duration of objective response for all patients was 13.2 months; and for patients obtaining a complete response (CR) the median duration of response was 26.3 months. Of the patients who achieved a CR, 47 % remained in remission at the time of analysis. The estimated 3-year survival rate was 63 %, while the median OS for patients obtaining a CR had not been reached.37 Recently presented data showed that the 4-year survival rate was 64 %. Of the 47 % patients with CR at 3 years, all remained in remission with no evidence of progression, suggesting that BV treatment may be curative for some patients (see Figure 3).38

On the basis of these data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to BV for the treatment of patients with HL after failure of auto-SCT or after failure of at least two prior combined chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-SCT candidates, and for the treatment of patients with sALCL after failure of at least one prior combined chemotherapy regimen.39

A study was also initiated to investigate if patients (21 with HL; eight with sALCL) who had previously responded to BV could achieve another remission with retreatment.40 The ORR was 60 % (30 % CR) in HL patients and 88 % (63 % CR) in sALCL patients. The estimated median duration of response for patients with an objective response was 9.5 months at study completion. Of the 19 patients with objective response, seven patients had not had an event of disease progression or death at the time of study completion; duration of response for these patients ranged from 3.5 to 28 months. Of the 11 patients with CR, 45 % had response durations of over 1 year. The study concluded that retreatment with BV was safe and feasible.40

A number of studies detailing the use of BV on named patient programmes have been published. Clinical outcomes in these ‘real use’ studies have been similar to those reported in the phase II clinical trials41–44 and have enabled patients to progress to auto-SCT or allo-SCT.

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre phase III study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BV and best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo and BSC in patients at high risk of residual HL after auto-SCT (the AETHERA trial), a total of 329 patients were enrolled in one of three high-risk categories: refractory to frontline therapy (59.6 %); relapse <12 months after frontline therapy (32.7 %); and relapse ≥12 months after frontline therapy with extranodal disease (7.6 %). The estimated 2-year PFS rate was 54 % and the estimated 2-year OS rate was 88 %.45

In a recent systematic review of six published prospective studies (n=302) of BV in relapsed/refractory HL and sALCL, meta-analyses were carried out to calculate the objective response rate (ORR), complete response rate (CRR) and partial response rate (PRR), and

found an ORR of 0.61, CRR of 0.38 and PRR of 0.25. High heterogeneity between the studies was found; however, the definition of relapsed/ refractory differed between investigators. The study concluded that BV demonstrated promising benefit but that larger study populations were needed in future.46 Another meta-analysis compared data from a phase II study of BV33 (n=102) with data from 17 historical studies (n=802) in patients with relapsed/refractory HL post-auto-SCT. The CR for BV (34 %) exceeded the estimated overall CR of the historical data (11.1 %).47

Brentuximab Vedotin as Salvage Therapy and as a Bridge to Stem Cell Transplantation

Based on the encouraging results from phase II studies, BV is currently being investigated in different disease settings. BV has been associated with manageable AEs in transplant-naïve patients with relapsed or refractory HL (the majority were chemorefractive), demonstrating that its antitumor activity is not limited to patients who received BV after auto-SCT.48 BV may therefore be used as a bridge to transplantation in patients who might not otherwise fulfil the criteria for autologous transplant intervention. A retrospective study examined data from 14 patients with refractory or relapsed HL who were treated with BV as single agent in a named patient programme, and had not received prior high-dose chemotherapy and auto-SCT due to refractory disease (n=9), comorbidity (n=4) and unknown reasons (n=1). In these patients, BV resulted in an ORR of 71 % with CR in 36 %, and allowed consolidating auto-SCT to be performed in four patients and allo-SCT in one patient.

Achieving a FDG-PET negative state prior to auto-SCT is desirable to optimise outcomes post transplant.15 A recent study therefore evaluated the role of BV in achieving FDG-PET-negative status in patients with platinum-refractory HL prior to auto-SCT. Treatment with BV converted 47 % of platinum-refractory patients to FDG-PET negative status. At the time of analysis, 87 % of patients had proceeded to highdose chemotherapy/auto-SCT.49 In a phase II study in which BV was incorporated into salvage therapy with the aim of normalising PET, patients (n=40) who achieved normalisation of PET proceeded to SCT while the remainder received two cycles of augmented ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide). The CR rate was 80 % after BV (with or without ICE), almost all (97.5 %) patients were referred for auto-SCT and 30 % of patients were able to avoid ICE salvage therapy.50 Another recent study has indicated that interim FDG-PET/CT might be a suitable diagnostic approach to predict response to BV in relapsed and refractory HL.51 In addition to acting as a bridge to auto-SCT, BV is an attractive option for reducing tumour burden to facilitate consolidative allogeneic SCT (allo-SCT), improving post-transplantation disease-free survival. Fifteen of the patients who participated in the pivotal phase II studies received consolidative allo-SCT following BV treatment.52 In a recent report, the 2-year PFS of these patients was estimated to be 66 % and the median PFS had not yet been reached. Eleven of the patients were alive and the estimated 2-year survival rate was 80 %.52

A retrospective analysis compared 23 HL patients who underwent reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) allo-HCT with no prior BV exposure with 21 additional HL patients who received BV prior to RIC allo-SCT. The patients who received BV prior to RIC allo-HCT in relapsed HL showed improvements in haematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI), CR status at time of transplant and reduced peri-transplant toxicity.53 In another study of patients who underwent allo-SCT (n=27), 52 % received BV prior to allo-SCT, and in seven patients, it was the last therapy prior to allo-SCT. In these seven patients the CR rate was 100 %, indicating that a BV-based transplant strategy is useful in this high-risk patient group.54

Brentuximab Vedotin in Relapsed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma following Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation

There are currently no effective therapeutic options for HL patients who relapse following allo-SCT. BV enhances the graft versus lymphoma response by the induction of immunogenic cell death and may therefore be a promising approach for relapsed HL after allo-SCT.55 A study (n=25) investigated BV in this setting.55 An overall ORR of 50 % was reported, with CRR of 38 %. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.8 months. Although most AEs were manageable, nine patients (36 %) discontinued treatment due to AEs. The study concluded that BV was potentially beneficial in selected patients with recurrent HL after allo-SCT.55 In a report of four cases of patients with HL that relapsed early after allo-SCT, BV in combination with donor lymphocyte infusions induced tumour-specific immunity and sustained clinical remission all patients.32

Brentuximab Vedotin as First-line Treatment

Given the high response rate in the relapsed setting and the manageable toxicity profile, incorporating BV into first-line therapy is an attractive option. In an ongoing phase II study, BV was investigated as front-line therapy in patients aged ≥60 years (n=13). Recently presented results indicated that of the 11 patients with a response assessment, the ORR was 82 % and CR rate was 64 %.56 This suggests that BV is a promising treatment option in this historically challenging population of patients who either declined or were not eligible for standard chemotherapy.

There is a strong rationale for combining BV with chemotherapy as front-line therapy. A phase I open-label dose-escalation study investigated BV in combination with the standard chemotherapy regimen of ABVD or a modified regimen of doxorubicin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (AVD) treatment in treatment-naïve patients with HL.57 Serious pulmonary toxicity was reported in 44 % of the ABVD group, leading the FDA to issue a formal warning against the use of BV with bleomycin. However, BV combined with AVD given every 2 weeks was generally well tolerated.57 In a phase II study of patients with newly diagnosed HL, BV is being investigated as part of targeted BEACOPP. Two modified BEACOPP regimens have been studied: BrECAPP (BV, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, procarbazine, prednisone) and BrECADD (BV, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, dacarbazine, dexamethasone). Preliminary results indicate that these regimens may be well feasible without compromising the efficacy associated with escalated BEACOPP.58

An ongoing phase III open-label, study, ECHELON-1, has the primary objective of comparing the modified PFS obtained with BV plus AVD versus that obtained with ABVD for the first-line treatment of advanced HL.59 The combination of BV and bendamustine is also being investigated in the treatment of relapsed/refractory HL and sALCL in a phase I/II study. Results to date (34 patients evaluable for response) indicate that the combination has a manageable safety profile and has achieved high CRR (82 %), with an ORR 94 %.60 This regimen therefore represents a promising approach that warrants further investigation.

Brentuximab Vedotin in Paediatric Patients

The use of BV is also being investigated in younger patient populations. Interim data from a phase I/II open-label, multicentre study with BV in paediatric patients diagnosed with CD30+ relapsed, refractory HL and sALCL yielded encouraging results. The phase I arm of the study established the recommended phase II dose of BV in paediatric patients as 1.8 mg/kg every 3 weeks, and found a CR or PR in 88 % of patients. In the ongoing phase II study, BV was generally well tolerated and showed an ORR to date of 64 %, including 21 % CR.61,62 Several other clinical studies in paediatric and younger adult patient populations are also underway.63,64

Brentuximab Vedotin in Other CD30-positive Malignancies

In addition to HL and sALCL, CD30 positivity has been reported in other malignancies.65–67 A phase II investigator-sponsored trial is evaluating the use of BV in patients CD30+ cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, including lymphomatoid papulosis, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma or mycosis fungoides. Among 56 patients enrolled to date, 48 patients have received at least two doses of BV. The ORR was 71 %, with CR in 35 %.65 An ongoing phase II study is evaluating BV in patients (n=62) with relapsed or refractory CD30+ NHL, including diffuse large cell B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL). To date, in DLBCL, an ORR of 42 % was reported with CR in 16 %; in other B-cell NHL, ORR was 22 % with CR in 11 %.66

Sequential treatment regimens with BV and chemotherapy are also being explored. In a phase I study, patients (n=39) with newly diagnosed CD30+ mature T/natural killer (NK)-cell lymphomas (an aggressive subset of NHL) received either sequential treatment with two cycles of BV followed by six cycles of the combination chemotherapy regimen CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) or the combination regimen of BV plus CHP. BV, administered sequentially with CHOP or in combination with CHP, demonstrated manageable toxicity and substantial antitumour activity: in the sequential regimen, ORR was 85 % with CR in 62 %. In the combined regimen, an ORR of 100 % was reported, with CR in 88 % and a 1-year PFS rate of 71 %.67 Based on these data, a phase III study, ECHELON-2, is comparing BV and CHP versus CHOP in the treatment of patients with CD30+ mature T-cell lymphomas.68

BV is also being tested in other CD30+ nonlymphomatous malignancies,69,70 relapsed/refractory T/NK lymphomas71 and in steroid-refractory graft versus host disease.72

Safety and Tolerability of Brentuximab Vedotin

Brentuximab vedotin has a manageable toxicity profile: treatmentrelated AEs include neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy (PN), nausea, fatigue, thrombocytopenia and diarrhoea.33,36 In the two pivotal trials, 54 % of patients experienced PN.73 Of these, grade 3 PN (sensory) was reported by 8 % and 10 % of patients in the HL and sALCL trials, respectively, leading to discontinuation in 8 %. Grade 3 PN (motor) was reported by 4 % and 3 % of patients in the HL and sALCL trials, respectively,73 leading to discontinuation in 3 %. The BV prescribing information recommended monitoring patients for PN and modifying the dosage accordingly.73 Most patients showed improvement or resolution of PN symptoms at follow-up: with complete resolution in 49 %, and partial improvement in 31 %. Neutropenia should be managed by dose delay and reduction.74

A retrospective analysis of the safety and efficacy of BV compared safety data for older (≥60 years, median age 66) and younger patients (<60 years, median age 32) with relapsed CD30+ lymphomas.75 Higher rates of anaemia (30 % versus 10 %), peripheral sensory neuropathy (60 % versus 46 %), fatigue (58 % versus 43 %) and AEs more than or equal to grade 3 (70 % versus 56 %) were reported in older patients, but the authors concluded that with appropriate monitoring, BV could be a useful treatment option for older patients with relapsed CD30+ lymphomas. In the study investigating retreatment with BV, the reported AEs were similar in type and frequency to those observed in the BV pivotal trials, with the exception of PN, which was observed in 69 % of patients; however, almost half (48 %) of the patients had pre-existing PN at baseline. Grade 3 or higher events were observed in 48 % of patients; these were generally transient and managed by dose modifications or delays. Deaths due to AEs occurred in three HL patients; none were thought to be related to BV retreatment.40,76

Since the approval of BV, several cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) have been reported.77–79 The link to BV is uncertain given that these patients have been exposed to multiple other agents, many of which can cause immunosuppression. This serious AE requires continuing monitoring and a new Boxed Warning highlighting this potential risk has been added to the drug label.80 BV should be discontinued if PML is suspected.73 Pancreatitis has recently emerged as a rare but serious toxicity associated with BV.81,82 Clinicians prescribing BV should evaluate patients who present with prolonged nausea and/or vomiting and abdominal pain for pancreatitis, and should consider pre-treatment biochemical assessments with serum lipase and/or amylase. Moreover, haematologists should be alert to the possibility of such an AE.

The long-term safety of BV is of concern in a patient group that has a high expectation of cure and many years of life ahead. To date, limited data are available on long-term safety, and concerns have been expressed over the depletion of T-cell memory that may result from targeting CD30. In studies to date, however, T-cell depletion has not resulted in clinically significant consequences.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

Brentuximab vedotin combines several main mechanisms that contribute to its potent antitumour activity. In two pivotal phase II trials, BV demonstrated excellent ORR and CR among patients with relapsed/ refractory HL and sALCL. It also has an acceptable toxicity profile, with the most common AEs, PN and neutropenia, being largely reversible. There is a need for more studies with longer follow-up to further assess the safety and efficacy of BV. Numerous ongoing studies are investigating the use of BV at different stages of disease treatment, both as monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy.

Brentuximab vedotin has the potential to act as a bridge to SCT, a valuable therapeutic indication. The FDA has changed the indication for duration of drug administration, allowing treatment beyond the previous 16-cycle limit. Studies are ongoing to examine the role of BV in the pre-auto SCT salvage therapy setting as well as in the post-auto-SCT maintenance setting for relapsed/refractory HL, and in the pre-allo-SCT setting, This success of BV represents a landmark in the development of ADCs and has changed the paradigm of the treatment of HL and sALCL in the relapsed/refractory setting. In the future, it may alter the landscape for earlier settings of treatment as well. ■