Marginal zone lymphoma subtypes

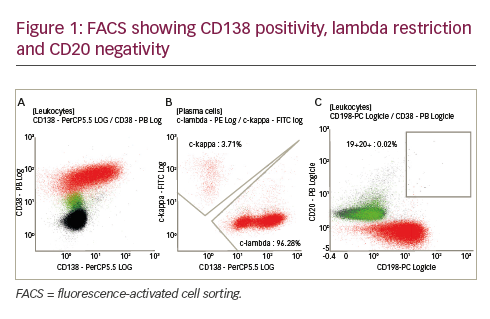

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) is an indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that accounts for 5.0%–10.0% of NHLs.1 There are three subtypes of MZL: extranodal (including mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT]), splenic and nodal.1 Extranodal MZL (EMZL) is the most common type of MZL and accounts for about 70% of all cases of MZLs, occuring in a variety of sites, such as the lung, skin, stomach or in the ocular tissue. Gastric MALT lymphomas are frequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. The second most common type is splenic MZL (SMZL), which accounts for about 20% of all cases.1 SMZL typically presents with splenomegaly, and patients may also have leukocytosis with circulating MZL cells. SMZL can be associated with hepatitis C virus infection. The least common type is nodal MZL (NMZL), which accounts for about 10.0% of all cases of MZLs.2 Overall survival rates are good, but relapses commonly occur. Similarly to other Indolent Lymphomas, MZL has the potential to transform into a high-grade lymphoma. In terms of diagnosis, MZL is sometimes a diagnosis of exclusion as it is typically negative for CD5, CD10 and CD23. The lack of CD5 distinguishes MZL from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma. Lack of CD10 distinguishes it from follicular lymphoma (FL). Lack of CD103 and CD25 distinguishes MZL from hairy cell leukaemia.3

Frontline treatment for marginal zone lymphoma

Frontline treatment can vary depending on the location of the disease. Treatment for H. pylori is recommended for patients with localized gastric MZL who are H. pylori positive, followed by observation. Radiation can be considered for early-stage non-gastric MALT or NMZL. For patients with SMZL who are asymptomatic, without progressive cytopenias, observation is typically recommended. When treatment is indicated, first-line rituximab or splenectomy can be considered. Similarly to SMZL, patients with NMZL or advanced-stage non-gastric MALT who are asymptomatic do not require immediate treatment and can be observed.1 For patients with advanced MZL who are symptomatic, treatment with rituximab or obinutuzumb with or without chemotherapy is typically used. The chemotherapy chosen is typically bendamustine, based on a study by the Study Group of Indolent Lymphomas (StiL), which showed a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 57.2 months for patients with MZL treated with bendamustine-rituximab (BR) compared with 47.2 months for those treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP).4

If induction therapy is successful, anti-CD20 maintenance therapy can be considered. One study in SMZL examined rituximab induction followed by maintenance in 108 patients.5 In this series, freedom from progression was improved with prolonged rituximab and was similar whether patients received 1 or 2 years of maintenance.5 The MAINTAIN study in Germany randomized patients with MZL who received BR to either observation or 2 years of maintenance rituximab. Preliminary results from this study have been presented in abstract form.6 PFS was improved for those who received maintenance (median not reached versus 92.2 months for observation), but, as in FL, overall survival was not improved with the use of rituximab maintenance therapy.6

Current therapies for relapsed/refractory marginal zone lymphoma

There are a number of treatment options for relapsed/refractory (R/R) MZL. Particularly for patients who had a prolonged response to anti-CD20 therapy previously, single-agent rituximab or obinutuzumab can be used again. In recent years, several novel agents have been introduced, such as lenalidomide, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, which can be considered as early as second line. The aim of this article is to introduce these classes of agents, with a particular focus on drugs that have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Lenalidomide-rituximab

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory drug, commonly used in multiple myeloma, that appears to have a number of antitumour effects in lymphomas, including effects on ubiquination of transcription factors, effects on tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and natural killer cells, and potential enhancement of rituximab-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.7 AUGMENT was a phase III randomized trial of lenalidomide plus rituximab (R2) versus placebo plus rituximab in patients with R/R FL or MZL.7 All patients were considered to be rituximab sensitive, meaning that the time to progression after the last rituximab dose was at least 6 months. Patients received oral lenalidomide 20 mg or placebo on days 1–21 of a 28-day cycle for 12 cycles plus rituximab once per week for 4 weeks in cycle 1 and day 1 of cycles 2–5. Of note, 18.0% of patients enrolled had MZL, with EMZL being the most common MZL subtype. The primary endpoint was PFS, which was significantly improved for lenalidomide plus rituximab versus placebo plus rituximab, with a hazard ratio of 0.46 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34–0.62; p<0.001) and median duration of 39.4 months (95% CI, 22.9 months – not reached) versus 14.1 months (95% CI, 11.4–16.7 months), respectively.7 While the majority of patients enrolled in this study had FL, AUGMENT suggests that R2 may be an effective, time-limited regimen for patients with R/R MZL. Neutropenia and leukopenia were by far the most common grade 3+ toxicities noted in the lenalidomide arm. Diarrhoea was more frequent for those treated with lenalidomide compared with placebo, but was mostly low grade (31.0% all grades, 3.0% grade 3+).7 Based on AUGMENT, R2 was approved by the FDA for use in R/R FL and MZL in May 2019.8

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors

PI3K inhibitors have also shown efficacy in treatment of R/R MZL. Several are now commercially available, and vary in terms of formulations (intravenous [IV] versus oral) and the isoforms of PI3K that are targeted. While PI3K inhibitors produce reasonable response rates in patients with R/R MZL (typically in the order of 50.0%), enthusiasm to adopt them has been dampened by toxicity. For example, the phase II study of idelalisib, which predominately targets the δ isoform, showed a 54.0% rate of grade 3 or higher diarrhoea in patients with R/R low-grade lymphomas.9

Of note, idelalisib was recently voluntarily pulled from the US market for the treatment of FL and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) on 18 January 2022 due to lack of confirmatory data after initial accelerated approval.10

Duvelisib

Another PI3K inhibitor, duvelisib, targets the PI3K δ and γ isoforms and was approved in 2018 for R/R CLL/SLL and R/R FL after two or more prior systemic therapies. The phase II DYNAMO study, which led to the approval of duvelisib in FL, included a variety of indolent NHL subtypes, including MZL.11 The overall response rate (ORR) was 47.3% in the overall DYNAMO study and 38.9% in patients with MZLs. Among all patients with indolent NHL, 88.4% experienced grade 3 or higher toxicities, which included diarrhoea, anaemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia as the predominant adverse events (AEs).11

Copanlisib

Copanlisib has a different side effect profile as a result of targeting the α isoform of PI3K in addition to the δ. Copanlisib can cause transient hypertension and hyperglycaemia, but appears to cause less gastrointestinal toxicity (8.5% grade 3 diarrhoea, no grade 4) than other PI3K inhibitors.12 CHRONOS-3 was a randomized phase III study of rituximab versus copanlisib plus rituximab (C+R) in relapsed indolent NHL.13 About 20.0% of those enrolled had MZL. This study demonstrated that C+R led to an improved PFS (21.5 months) compared with rituximab alone (13.8 months), but doubts have been raised about the true impact of rituximab on outcomes in the C+R arm; perhaps single-agent copanlisib would be as effective or nearly as effective as the combination.13 Copanlisib is tolerable and can be effective, but the downside is that copanlisib requires weekly IV administration. Thus, there has been a desire to develop an oral PI3K inhibitor with less toxicity to make this class of drugs a more appealing option.

Umbralisib

Umbralisib gained FDA approval for the treatment of R/R MZL in February 2021.14 Umbralisib is an oral PI3K inhibitor that is unique, as it targets both PI3K δ and casein kinase-1 ε (CK1ε). It is particularly selective for PI3K δ, and it is the inhibition of PI3K gamma that is believed to be responsible for autoimmune toxicities such as diarrhoea that are associated with other drugs in this class. Targeting CK1ε affects expression of certain oncogenes and the β-catenin/wingless-type MMTV integration site (WNT) signalling pathway. This effect on the WNT pathway may modulate the functions of regulatory T cells, also potentially leading to decreased autoimmune toxicity.15

UNITY-NHL was phase II open-label trial of single-agent umbralisib in patients with R/R low-grade lymphoma who had at least one prior therapy and prior therapy with an anti-CD20 antibody.15 The study included 69 patients with MZL. The ORR in MZL was 49.3%, with 15.9% complete response (CR); there are no available data on specific MZL subtypes. Across NHL subtypes (36/42), there was a reduction in tumour burden in 86.4% of patients who had received 9 or more cycles prior to the data cutoff, with a median time to initial response being 2.7 months. AEs were tolerable in most patients and there were no deaths. Ten patients (4.8%) discontinued therapy due to AEs possibly related to umbralisib. A total of 41 patients who underwent at least six cycles (median age 66 years) and were on therapy for a median duration of 10.1 months were evaluable for AEs, with diarrhoea being the most prevalent AE (10.0% grade 3 or higher). Other AEs included nausea, transaminitis, headache, cough and fatigue, and were mainly grade 2 or better.15 Thus, umbralisib appears to have similar efficacy to other PI3K δ-targeted agents but with a more favourable toxicity profile.

Umbralisib is approved as a single oral agent, but response rate may be better when combined with an anti-CD20 antibody. UNITY-NHL also studied the combination of umbralisib with the anti-CD20 antibody ublituximab (U2) in R/R indolent NHL. A total of 72 patients with MZL received U2, all of whom had previously received an anti-CD20 therapy. ORR, which was the primary endpoint, was 68.0%. Common AEs were similar to those for umbralisib alone; 3.0% of patients experienced grade 3+ diarrhoea.16

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Ibrutinib

The oral BTK inhibitor ibrutinib was approved in 2017 based on a single-arm phase II study of patients who had received at least one prior therapy.17 ORR was 58.0% and response rates were similar among MZL subtypes (63.0%, 47.0% and 62.0% for MALT, NMZL and SMZL, respectively). Use of ibrutinib can be limited by its toxicity profile, including increased risk of bleeding and bruising, atrial fibrillation, pneumonia and hypertension.18 Overall, 19.0% of patients in this phase II study discontinued therapy due to AEs.17 Thus, second-generation BTK inhibitors have been developed that more specifically target BTK, aimed at improving efficacy with fewer off-target toxicities.

Zanubrutinib

Zanubrutinib, one of the new second-generation, covalent, BTK inhibitors, has been assessed in the MAGNOLIA single-arm phase II study.19 The inclusion criteria were similar to UNITY-NHL in that patients were required to have at least one prior therapy and prior anti-CD20 therapy. A total of 68 patients were included with the following subtypes: EMZL/MALT (38.2%), NMZL (38.2%), SMZL (17.6%) and indeterminate MZL (6.0%). Median duration of drug exposure was 59.1 weeks. The median number of prior therapies was at least 2, and 32.0% of patients had disease considered refractory to last treatment. The ORR was 68.2% (64.0%, 76.0%, 66.7% and 50.0% for the above subtypes, respectively). CR was achieved in 25.8% of patients, and CR rates for the above subtypes were 40.0%, 20.0%, 8.3% and 25.0%, respectively. Most AEs were grade 1 or 2, including diarrhoea, bruising, constipation, pyrexia, back pain and upper respiratory infections. Neutropenia was the most common grade 3 or greater AE, at 10.3%. No deaths were attributed to zanubrutinib, and only 4 patients discontinued treatment due to AEs, two of which were COVID pneumonia, meaning that only 2.9% of patients discontinued due to non-COVID AEs.18 Thus, zanubrutinib appears to be an effective option that may be more tolerable than other available agents.

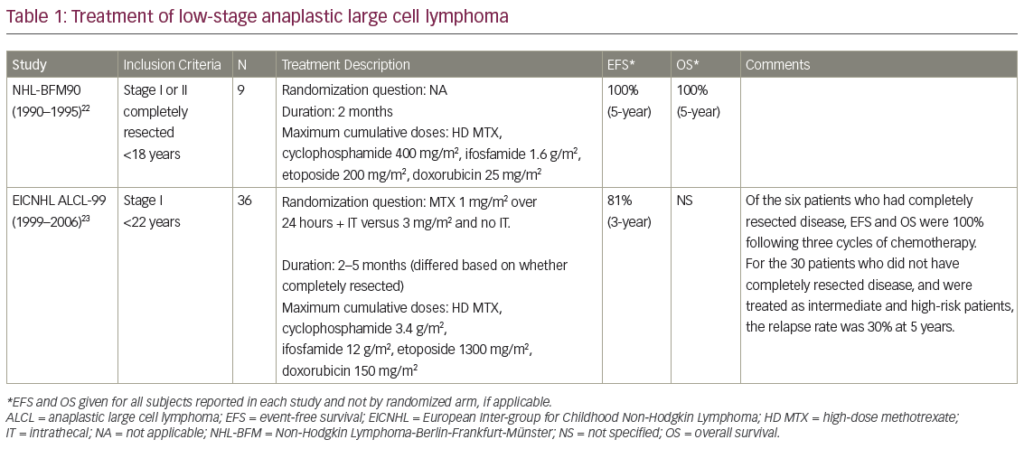

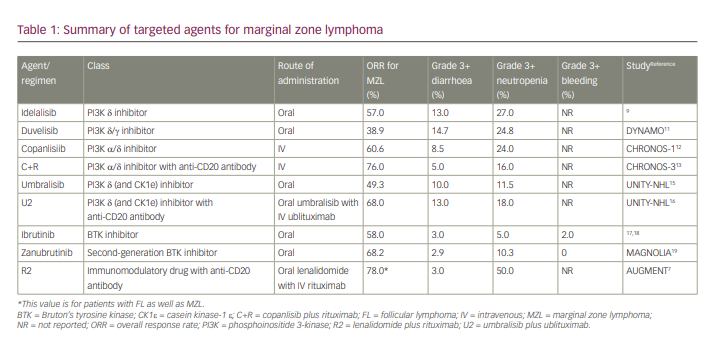

A summary of agents for the treatment of MZL is shown in Table 1.

Is there a role for venetoclax?

The B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax is an effective agent in some subtypes of indolent lymphoma, namely CLL/SLL and Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia.20,21 Experience with venetoclax in MZL is limited. In the initial phase I study of venetoclax in R/R NHL, 3 of the enrolled patients had MZL, 2 of whom had a response (ORR 67.0%).22 Both responses were partial responses, and the duration of response for the 2 patients with MZL was 2.3 months and 23.6 months, respectively.22 A single-centre retrospective analysis of 34 patients treated with off-label venetoclax included 2 patients with MZL.23 The ORR for the whole cohort, which included a wide range of histologies and both high- and low-grade lymphomas, was 26%. The CR rate was only 3.0% for the population as a whole. Data were not available specifically for outcomes for the 2 patients with MZL. A phase II trial of venetoclax with ibrutinib, which enrolled 14 patients, has been presented.24 In this study, patients were started on ibrutinib monotherapy, and then venetoclax was added in a stepwise fashion. The combination was tolerable with no cases of tumour lysis syndrome and only one discontinuation due to toxicity. The primary endpoint was CR rate at week 16. At the time of presentation, the median follow-up was 9.7 months. ORR at 16 weeks by positron emission tomography was 84.0%, and CR rate was 42.0%. Two patients developed progressive disease after 7 and 11 months of therapy, respectively.24 While well tolerated, venetoclax appears to have limited efficacy as a single agent in MZL. There could be a role for combination with other targeted agents, namely BTK inhibitors, but data are extremely limited.

Future treatment options for marginal zone lymphoma

While the number of approved treatment options for MZL has expanded significantly in the past few years, additional novel and potentially effective therapies continue to be developed. CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has been commercially available for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) for some years, with perhaps curative potential.25 A CAR T-cell product was approved for FL in March 2021 based on the phase II ZUMA-5 study of R/R indolent NHL, which showed an ORR of 92.0%, a CR rate of 76.0% and an estimated 12-month duration of response of 72.0%.26 ZUMA-5 also included 22 patients with R/R MZL. In the patients with MZL, ORR was 85.0% and CR was 60.0%. Thus, CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy appears to be effective in low-grade lymphomas, including MZL.

Bispecific antibodies targeting CD20 on the malignant B cell and CD3 on T cells have generated excitement for the treatment of other lymphoma subtypes, namely DLBCL and FL. While still somewhat early in development, these are ‘off-the-shelf’ drugs, some of which have subcutaneous formulations for ease of adminsitration. The phase I study of the anti-CD20–anti-CD3 bispecific odronextamab presented at the 2020 American Society of Hematology annual meeting included 6 patients with MZL (about 5.0% of patients enrolled).27 In the overall population, median number of prior therapies was 3, and 66.9% of patients were considered refractory to alkylating agents and an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Response rates have been particularly encouraging for this drug in FL (approximately 93.0% ORR for doses of 5 mg or higher), but response rates for MZL have not yet been presented.

Mosunetuzumab is another CD20–CD3 bispecific antibody undergoing clinical investigation. A phase I study enrolled patients with multiple subtypes of R/R B-cell NHL.28 The majority of patients enrolled had DLBCL or transformed FL (56.0%). In the overall study population, the median number of prior lines of therapy was 3. Overall, 67.0% of patients were considered refractory to monoclonal anti-CD20 therapy, and 63.0% were considered refractory to the last prior therapy. ORR was 41.0% for all histologies, and responses were particularly encouraging in FL (61.0%). There was minimal representation of patients with MZL in the data presented: 1 patient had MZL and 1 patient had transformed MZL. Both of these patients had at least a 50.0% change in tumour volume from baseline.26 CD20–CD3 bispecific antibodies have favourable safety profiles and encouraging responses, particularly in FL, which is expected to lead to greater investigation of these agents in low-grade lymphomas such as MZL.

Conclusions

MZL is an indolent lymphoma with three major subtypes: extranodal, splenic and nodal. Gastric MALT, a subtype of EMZL, can be treated with H. pylori-directed therapy if associated with H. pylori infection. Many patients can take an active surveillance approach if asymptomatic at diagnosis. Otherwise, initial therapy typically consists of anti-CD20 therapy with or without bendamustine and with or without maintenance anti-CD20 therapy. The choice of therapy at relapse will vary and will need to take into consideration the agent(s) used as first-line therapy. Re-treatment with single-agent rituximab or obinutuzumab can be considered as second-line therapy if anti-CD20 therapy was previously effective and disease volume is low or comorbidities are present. For patients with higher disease burdens, we typically use BR if previously treated with anti-CD20 antibody monotherapy. If BR was used as first-line therapy, our preference would be to use rituximab with lenalidomide (R2) as second-line therapy. This favouring of R2 over a single-agent BTK inhibitor or PI3K inhibitor is driven by the time-limited nature of the R2 therapy, as well at its efficacy. For subsequent relapses, we opt for BTK inhibitors or PI3K inhibitors. The decision between these two therapies is primarily based on toxicity profile, given that therapy is anticipated to be indefinite. Our bias is towards zanubrutinib based on the MAGNOLIA data, but there may still be hesitation to use a BTK inhibitor in a patient at high risk of bleeding or with a history of arrhythmia. In those cases, a PI3K inhibitor may be preferred. While copanlisib appears to have a high response rate and less autoimmune toxicity, its IV formulation may be a barrier to use for some patients. In those cases, where an oral option is strongly preferred, we favour umbralisib, given the side-effect profile to date. Limited data suggest that adding anti-CD20 antibodies may improve responses to PI3K inhibitors, but to date no randomized data looking at PI3K inhibitors with or without anti-CD20 therapy have been presented.

While several agents are currently available in the R/R setting, we have room to improve on the currently available therapies in a number of ways: improve efficacy, lower toxicity and develop more options with a defined duration of therapy. Preliminary data on CAR T-cell therapy show a high response rate in MZL, but this comes with the need for pheresis, hospitalization at most sites, and risk of cytokine release syndrome and neurological toxicity.26 Perhaps more practical for most patients will be bispecific antibody therapies, which have shown encouraging responses in FL, but so far experience in MZL patients is extremely limited. We eagerly await new therapies or thoughtful combinations of therapies that will improve responses, limit duration of therapy and decrease toxicity in patients with MZL.