Urothelial cancer (UC) is a common malignancy both in men and women. More than 400,000 patients are diagnosed every year and approximately 150,000 die from this disease, worldwide.1 At the same time, 5-year survival rate has only been moderately increased during the last 30 years.2

UC may arise throughout the urinary tract (urinary bladder, ureter, renal pelvis, urethra) but more than 90% of them occur in the bladder. The major histological subtype is transitional-cell carcinoma (92%), while pure squamous and adenocarcinomas are rare (2%).3 Mixed variants are more common than pure non-transitional histologies. Tumour stage at diagnosis represents the most important prognostic indicator. Non-muscle invasive tumours (Tis, Ta, T1) represent almost 70% of the newly diagnosed cases, and are associated with excellent prognosis (almost 90% 5-year survival) compared to muscle-invasive (≥T2) tumours (less than 65% survival).4

The chemosensitivity of UC has long been accepted. Taking into consideration that 20% of muscle-invasive tumours are associated with metastatic disease at diagnosis and 40–50% of initially non-metastatic disease recurs after local therapy, it is obvious that the role of systemic chemotherapy is important in a sizable percentage of patients. Furthermore, the high probability of relapse after local therapy has introduced the concept of peri-operative chemotherapy as a means of reducing relapse rates. In this review, we discuss the current status of systemic chemotherapy in muscle-invasive UC.

Chemotherapy for localised muscle-invasive urothelial cancer

The first step in the management of muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT) aiming at maximal resection and accurate diagnosis of the disease. Smooth muscle must be included in the specimen. After TURBT, disease should be staged with at least computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. In case of no metastases, the optimal modality for local therapy should be considered and discussed with the patient. Traditionally, radical cystectomy accompanied by pelvic lymphadenectomy has been the standard of local treatment.5 Despite improvement in surgical techniques, however, locoregional or distant failure occurs in about 50% for T3 cases.6 In this setting, chemotherapy has been widely used to eliminate micrometastatic disease.7 In addition, a considerable proportion of patients cannot undergo cystectomy due to co-morbidities or noncompliance.8 Recent data, suggest that radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy can achieve comparable outcomes regarding local and distant control to radical cystectomy.9

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Preoperative (neoadjuvant) cisplatin-based chemotherapy is strongly recommended as standard treatment by both medical oncology (The National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], The European Society for Medical Oncology [ESMO]) and urological associations (The European Association of Urology [EAU]).8–10 The first clinical trial investigating this approach was the BA06 30894 trial which administered three cycles of cisplatin, methotrexate and vinblastine (CMV) prior to definitive radical cyctectomy or radiotherapy versus definitive local therapy alone. Long term follow-up revealed 16% decrease in the risk of death and almost a 6% absolute increase in 10-year survival rate.11

The second well-designed randomised study (SWOG 8710/INT-0080) compared treatment with the MVAC regimen (methotrexate–vinblastine–doxorubicin–cisplatin) followed by radical cystectomy versus radical cystectomy alone. A clinically meaningful improvement in overall survival (OS) was revealed on final analysis (77 versus 46 months; p=0.06). Importantly, response to MVAC was an important prognostic factor: no evidence of residual disease (pT0) at cystectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, predicted an OS of 85% at 5 years.12 Although MVAC proved its efficacy as preoperative treatment, its toxicity (44% Grade 4 neutropenia) limits its use. Consequently, new strategies were implemented in order to reduce toxicity and lead to shorter diagnosis-to-cystectomy times. Dose-dense MVAC, given every 15 days with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) support was tested versus conventional MVAC in the metastatic setting, leading to a statistically significant improvement in median progression-free survival (PFS: 9.1 versus 8.2 months; p=0.037),13 while long-term follow up suggested improvement in OS too.14 These data were extrapolated in the neoadjuvant setting and were consistent with the findings of two single-arm, phase II trials.14,15

Another combination gaining use in the preoperative setting is the gemcitabine-cisplatin (GC) regimen. GC has shown similar efficacy and lower toxicity than MVAC in the metastatic setting.16 Real-world data by Galsky et al. revealed that GC is more commonly used as neoadjuvant chemotherapy leading to similar pathalogic complete response (pCR) rates and survival outcomes.17 These data were also confirmed in retrospective data from 19 institutions internationally.18 The GC combination has recently been investigated in its dose-dense form, and given the fact that it has produced similar results in phase II trials, it is anticipated to gain more acceptance in clinical practice.19

Despite the high level of evidence supporting its use, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is underutilised. Several reasons have been suggested to explain this deviation from existing guidelines. The theoretical detrimental effect of delaying definitive treatment during neoadjuvant chemotherapy accounts for the reluctance of urologists to refer patients for this modality. In addition, only 50% of candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy are eligible for cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy,20 which is the only treatment that showed a benefit from this approach. Recent advances in molecular classification of MIBC have produced interesting results in identifying patients who are more likely to benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy and this way can prevent its utilisation in patients who are less likely to respond or these who are going to have excellent progonosis with cystectomy alone.21 Fortunately, according to National Cancer Institute database, there has been a recent increase in the percentage of patients on neoadjuvant approach, from 7.6% in 2006 to 20.9% in 2010.22 The importance of multidisciplinary approach and careful selection of patients for neoadjuvant chemotherapy are critical factors contributing to this progress.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

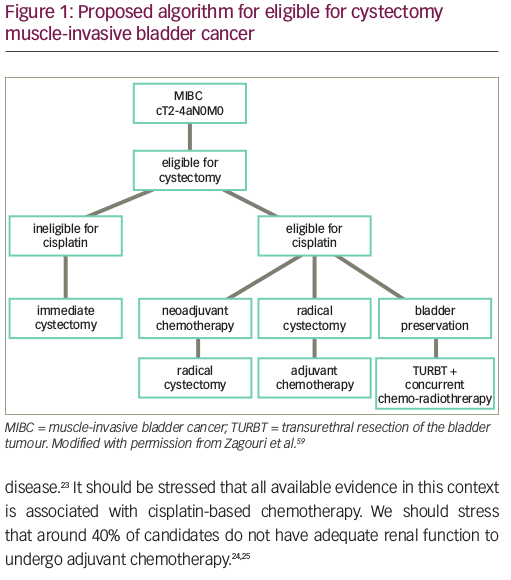

Reduction of recurrence rate and thus, prolongation of survival, is the rationale behind the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. This is more relevant when disease is not confined to the bladder (pT3-pT4, N+ disease). The 5-year survival rate is 30% for N+ disease and almost 50% for T3 disease.23 It should be stressed that all available evidence in this context is associated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. We should stress that around 40% of candidates do not have adequate renal function to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy.24,25

Few randomised trials have evaluated the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for UC. Most of them were stopped early due to poor accrual. Review of these trials revealed a number of methodological flaws: low accrual with insufficient sample size, ineffective chemotherapy regimens, inadequate statistical methodology.26–32 A meta-analysis of six early randomised trials, including 491 patients, published in 2005, revealed a global reduction of the risk of death of 25% (hazard ratio [HR]=0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.60–0.96, p=0.019) with an absolute gain in survival of 9% at 3 years.33

The largest randomised trial on adjuvant treatment was published by European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; trial 30994).34 It was also stopped early due to slow accrual after randomising 284 patients instead of the pre-planned number of 660. It failed to meet its primary endpoint concerning OS benefit (adjusted HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.56–1.08, p=0.13) but it showed a significant increase in 5-years PFS for adjuvant chemotherapy arm (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.4–0.73, p<0.0001).

To conclude, adjuvant chemotherapy on UC remains a topic of debate. In spite of obvious advantages (administration without delay of surgical procedures, accurate staging based on cystectomy specimen) it is not supported by the level of evidence associated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which remains the standard perioperative therapy in bladder cancer. Nevertheless, EAU, ESMO and NCCN guidelines suggest the use adjuvant chemotherapy in high risk patients after cystectomy (extra-vesical or node-positive disease) who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 1).8–10

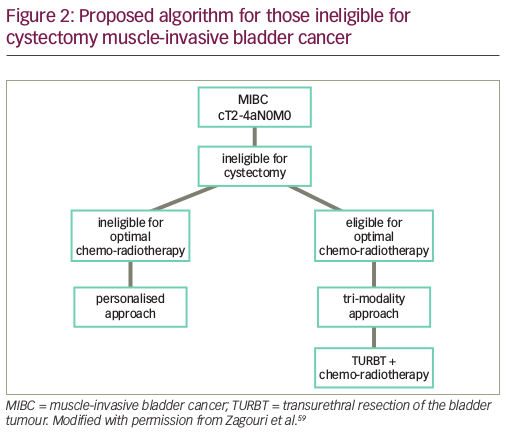

Bladder-preservation approach – non-cystectomy candidate

A sizable proportion of patients with MIBC are unfit for or unwilling to undergo cystectomy. This has fuelled research on bladder-preservation strategies as an alternative to radical cystectomy. Bladder-preserving strategies ideally involve a tri-modality approach: maximal TURB-T followed by combined radio-chemotherapy (Figure 2).

This importance of the addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy was recently shown by James et al.: the addition of chemotherapy ith 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and Mitomycin-C to radical radiation, increased locoregional control, which was considered a surrogate for OS.35 Although cisplatin is the most studied drug in the concurrent chemotherapy setting, this is a useful approach, specifically in the cisplatin-ineligible population.

The role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the context of radio-chemotherapy remains unclear. Subanalyses of the previously mentioned trial suggested a benefit by the administration of chemotherapy prior to the combined modality but the true value of this strategy can only be defined in randomised trials.

Chemotherapy for advanced urothelial cancer

Chemotherapy represents the mainstay of management of advanced (pT4b, or N+) or metastatic disease (M1). Nevertheless, multidisciplinary approach and local control, remain crucial factors to obtain optimal results especially in patients with lymph node disease only.36

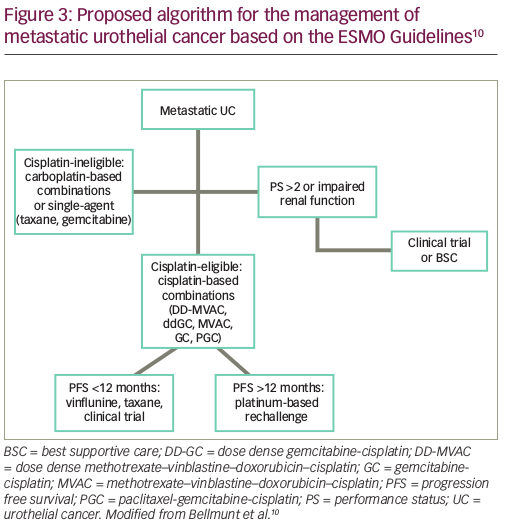

Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy represents the treatment of choice in advanced disease. The combination of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) produced superior response rates and survival than single agent cisplatin (12.5 versus 8.5 months); although, at the cost of increased toxicity.37 The prognosis of patients following cisplatin-based chemotherapy has been defined by the MSKCC algorithm, which combines Karnofsky performance status (KPS) and the presence of visceral metastases.38–39

Efforts to improve upon the efficacy of MVAC have failed, but more tolerable regimes have been developed. The EORTC 30924 trial investigated the dose dense (DD) (or accelerated) version of MVAC in an effort to control haematological toxicity.40 DD-MVAC showed a significant increase in complete response (CR) (21 versus 9% in the standard MVAC standard arm, p=0.009) and in PFS (9.1 months, compared with 8.2 months with MVAC, p=0.037). After 2 years, the probability to be free from progression was more than doubled for patients receiving DD-MVAC (24.7 versus 11.6%, p=0.037). Although survival seems to favour the DD-MVAC arm, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.122). DD-MVAC permitted delivery of twice the dose of cisplatin and adriamycin compared to MVAC with less haematologic toxicity due to the use of GCSF.40

A phase III randomised trial of 405 patients was conducted to compare GC with MVAC.40,41 Response rates (49% versus 46%), time to progression (median: 7.4 versus 7.4 months) and OS rates (median OS 13.8 versus 14.8 months; p=0.75) were similar in both arms. More importantly, GC was better tolerated than MVAC, with 63% of cycles administered with no dose modifications compared with 37% dose modifications in the MVAC arm. Patients on the GC arm experienced less grade 3 or 4 neutropenia (71% versus 82%), neutropenic fever (2% versus 14%), and neutropenic sepsis (1% versus 12%); and grade 3 or 4 mucositis was significantly less common on the GC arm (1% versus 22%), as was the toxic death rate (1% versus 3%).40 The equivalent efficacy and better tolerability profile of the GC regimen has led to its adoption as the preferred, standard first-line treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic bladder cancer in the community.

Dose-dense GC with GCSF support was compared to DD-MVAC in a Greek trial.42 Efficacy (median OS, median PFS) were similar between the two groups (DD-MVAC versus DD-GC; median OS: 19 versus 18 months; p=0.98, median PFS: 8.5 versus 7.8 months; p=0.36). Toxicity marginally favoured DD-GC (grade ≥3 50% DD-MVAC versus 44% DD-GC) and significantly more patients received at least six cycles of DD-GC compared with DD-MVAC (85 versus 63%; p=0.011). Thus, both DD-GC and DD-MVAC remain viable options in the cisplatin-eligible population.

Platinum-containing triplets or non-platinum containing regimens have been studied in a series of trials. They have produced interesting results but the toxicity profile of triplets and the well-established results of platinum-containing doublets have turned them not applicable in everyday practice. Specifically, PGC regimen (paclitaxel-gemcitabine-cisplatin) was studied in the EORTC 30987 trial,43 but failed to produce significant benefit in OS (15.8 months with PGC versus 12.7 months with GC; HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72–1.02, p=0.075) or PFS (8.3 months with PCG, 7.6 months with GC; HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.74–1.03, p=0.113). Only overall response rate (ORR) improved (55.5 versus 43.6% for PCG versus GC, respectively, p=0.0031) to the cost of more febrile neutropenia in PGC.

Cisplatin ineligible patients comprise about 50% of the total population of advanced UC.20 Carboplatin-based chemotherapy has been proposed as the standard in this population. The EORTC 30986 phase II/III trial compared gemcitabine-carboplatin (GCa) combination with methotrexate–carboplatin and cinblastine (M-CAVI), obtaining similar results in terms of OS (8.1 versus 9.3 months for patients treated with M-CAVI and GCa, respectively, p=0.64) and PFS (4.2 months for M-CAVI arm and 5.8 months for GCa, p=0.75) but a significantly better toxicity profile in patients treated with GCa.44 De Santis et al. investigated a non-carboplatin regimen, vinlunine-gemcitabine, versus vinflunine-carboplatin in the JASINT1 trial.45 Both doublets offered similar PFS (5.9 versus 6.1 months respectively) and OS (14 versus 12.8 months) results. It should be noted that only performance status (PS) 0 and 1 patients were eligible for enrolment, which makes this population more favourable than a typical cisplatin-ineligible cohort. The value of carboplatin in the unfit population is clearly shown in the data from the RISC database where carboplatin treated patients had a longer survival compared to the untreated population (9.5 versus 6.8 months).46 Nevertheless, prognosis remains poor and more effective therapies are urgently needed for these patients.

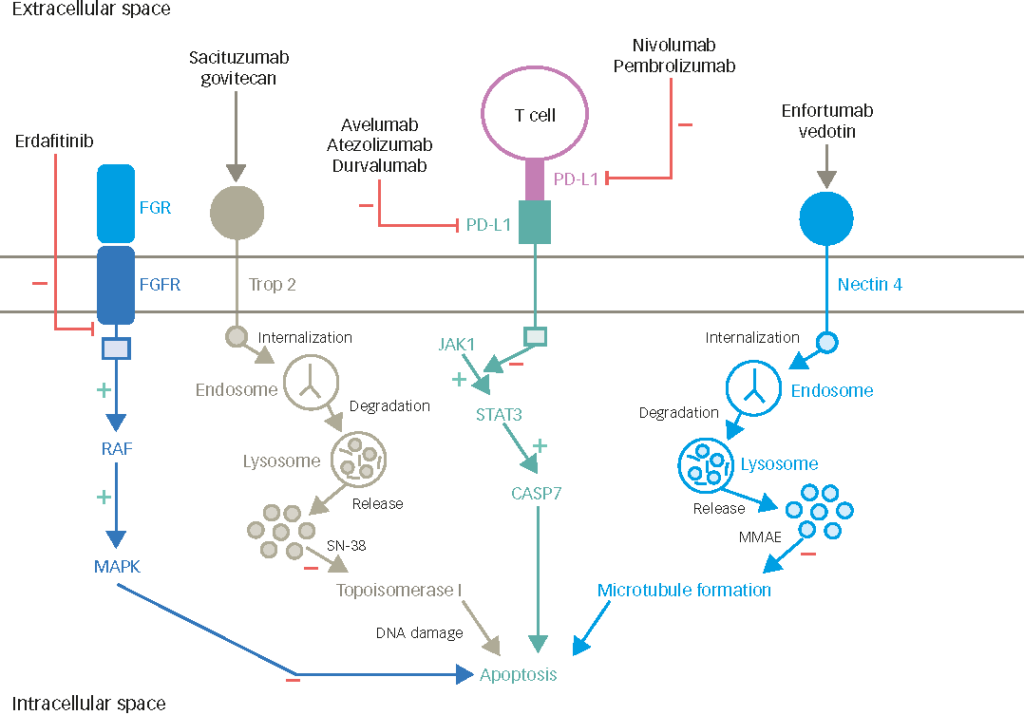

Immunotherapy is probably the most promising new comer in management of metastatic UC. Its role is more evident in the unfit for cisplatin population. Results from IMvigor210 trial cohort 1, regarding the use of atezolizumab (anti programmed death-ligand 1 [PD-L1] antibody) as first-line therapy in cisplatin-ineligible locally advanced/metastatic UC, show that responses occur in all subgroups, irrespective of PD-L1 status (22% IC2/3, 19% all).47 Pembrolizumab has also produced meaningful and durable responses in the same population in the KEYNOTE-052 trial.48 With a median follow-up time of 7.8 months, the ORR was 28.6% (95% CI 24, 34) and the median response duration was not reached (range +1.4, +17.8 months). These results have led to FDA approval of atezolizumab and pembrolizumab as first-line treatment in the cisplatin-ineligible population. More effort is ongoing concerning incorporating immunotherapy in first-line setting, and this is going to be answered by the IMvigor130 trial which has been recently modified to compare atezolizumab monotherapy versus its combination with chemotherapy in both cisplatin-eligible and -ineligible groups.49

Most patients with advanced UC will relapse after first-line treatment. Karnofsky Performance Score (KPS), liver metastatic disease, and haemoglobin level are significant prognostic factors in this setting.50 The optimal treatment for these patients remains undefined. A meta-analysis by Raggi et al. proved that combinations did not provide any significant improvement in OS, but only a statistically significant benefit in response rate.51 Therefore, they are only suggested when disease control matters in case of severe symptoms.

ESMO guidelines suggest choosing platinum-rechallenge based on the first-line PFS (Figure 3);10 although, this practice is not supported by a high level of evidence. Vinflunine, a novel vinca alkaloid, is only approved in Europe for second-line treatment of UC, based on the results of a phase III trial, where a significant survival benefit over best supportive care was shown only in the patients treated according to study protocol.52 Lately, angiogenesis inhibition using the combination of a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-2 inhibitor, ramucirumab with docetaxel has shown statistically significant prolongation of PFS in a phase III trial; more data on OS are anticipated before regulatory approval.53

Immunotherapy in second-line treatment of urothelial cancer

Lately, the landscape of second-line treatment seems to be changing with the evolving role of immunotherapy. In a phase III trial, pembrolizumab produced significantly longer OS compared to single-agent chemotherapy. In this trial (KEYNOTE-045) pembrolizumab was compared to standard second-line chemotherapy (taxane-based, vinflunine).54 Significant prolongation of OS was recorded in both unselected (10.3 versus 7.4 months) and PD-L1 selected population (8 versus 5.2 months). This is the first time, a novel agent demonstrates activity in prolonging OS on this setting compared to chemotherapy. In addition, the non-randomised IMvigor210 study showed promising results in a similar population.55 Stratification of patients according to PD-L1 status was associated with higher benefit, but considerable efficacy was also observed among PD-L1 non-expressors. Nivolumab, in the CheckMate275 trial, has also proven its efficacy in the same setting, producing high response rates irrespective of the PD-L1 expression.56 Therefore, other markers, such as mutational load or molecular subtype are currently studied as potential means of selection of patients likely to benefit from these therapies.57

Conclusion

UC has long been recognised as a chemosensitive disease, and systemic chemotherapy plays a crucial role in the management of localised and advanced disease. Unfortunately, there has been a paucity of progress during the last 15 years, in this area. Recently, the advent of modern immunotherapy seems to offer new effective choices for patients with advanced UC.

Neoadjuvant use of cisplatin-based combinations has shown survival benefit, and together with radical cystectomy should constitute the cornerstone of early disease management.8–10 Most importantly, Galsky criteria concerning fitness for cisplatin provide a useful tool for clinicians, in order to select patients with substantial benefit from cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

The discovery of predictive biomarkers to determine the most effective therapeutic strategy for a given patient is critical. This holds true for cytotoxic chemotherapy as well as for immunotherapy. Genetic profiling seems to be worth studying in this context. On the other hand, PD-L1 expression on UC cells has been correlated with a worse prognosis, but unfortunately, PD-L1 expression on tumour and immune cells has proven to be unreliable as the sole determinants of response to PD-1 blockade.58 Technical issues, tumour heterogeneity and the dynamic nature of its expression, may represent some of the reasons for this limitation. More insightful knowledge of immune system principles could improve our efforts to explore new biomarkers in advanced UC.