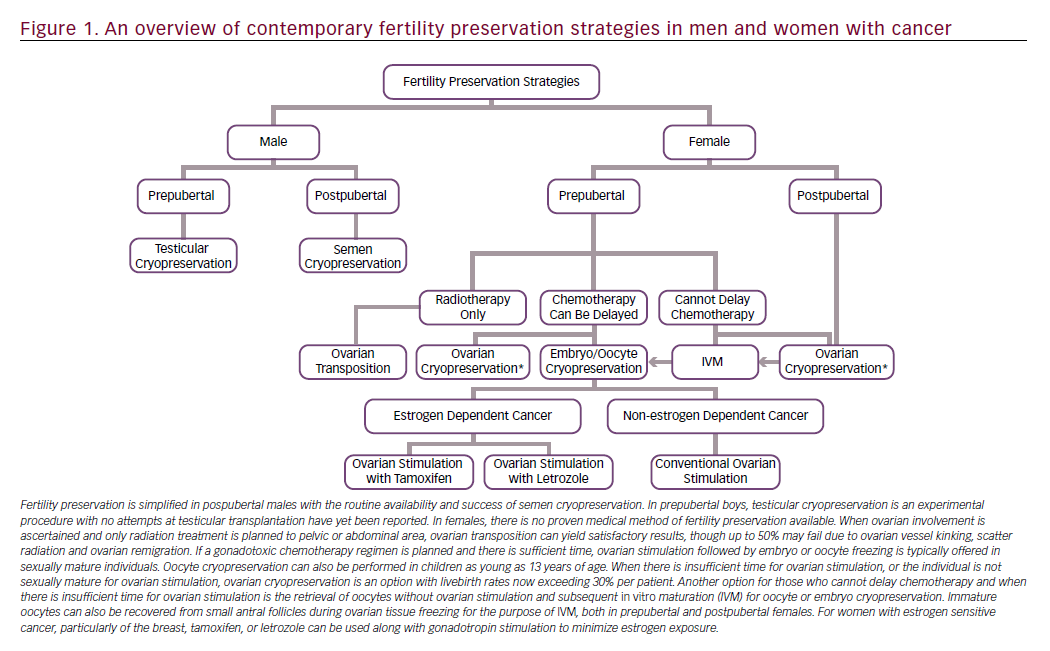

It has been estimated that approximately 1% of all females may be exposed to some form of gonadotoxic cancer treatment by the age of 45.1 Given the quality of life consequences of cancer-treatment-induced infertility and ovarian failure, fertility preservation becomes an essential component of cancer care. The fertility preservation field has shown significant evolution within the past 17 years but it is not without its controversies. While embryo and oocyte cryopreservation are considered established techniques, various discussions continue around ovarian cryopreservation as well as the utility of Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone Agonists (GnRHa).

To us, ovarian cryopreservation followed by transplantation is the easier one to address first. The question revolves around whether it should still be considered experimental. Recent reports including some of ours put the number of live births over 60, with more than a third of women having at least one child after an ovarian transplant.2,3 Ovarian cryopreservation has several advantages over gamete freezing techniques, as after transplantation, normal ovarian endocrine function can be restored and fertility can be achieved without assisted reproduction techniques. There is no need for ovarian stimulation or a significant delay before chemotherapy as tissue is harvested via a brief outpatient laparoscopic procedure. We have shown the safety of ovarian tissue harvesting in cancer patients,4 even in those with multiple medical issues.

Why then, is ovarian tissue freezing still considered experimental? Among the several reasons that have been cited are the relative brevity of experience, lack of randomized studies-especially on the risk of reseeding cancer cells, and the unpredictable duration of ovarian function after a transplant. We performed the first case of autologous ovarian transplantation with cryopreserved tissue in 1999,5 which successfully restored ovarian endocrine function in a surgically menopausal young woman. There is now 17 years of experience with this procedure. Animal as well cadaveric studies suggest by and large that micrometastasis to the ovaries is not a real concern especially for the cancer types for which ovarian tissue freezing is commonly performed. And finally, with the advent of new transplant techniques, like the one we recently reported,2 ovarian function becomes more predictable after transplants. Given this profile, ovarian cryopreservation stands as a valid method of fertility preservation. This is especially true when the patient is a child and hence cannot be a candidate for egg freezing, or when there is insufficient time or contraindication for ovarian stimulation.

That brings us to the controversy regarding ovarian suppression with GnRHa to protect ovaries during chemotherapy. The recent randomized trial by Moore et al. suggested that Zoladex® (AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, UK) may preserve ovarian function during chemotherapy in women with

Estrogen Receptor (ER)+ breast cancer.6 We have already discussed the weaknesses of this and similar studies elsewhere.7–9 It appears that the studies on the subject are split with some favoring GnRHa while others showing no benefit. We analyzed this contradiction in a recent report,8 and found that the studies that utilized proper markers of ovarian reserve did not find any benefit for ovarian suppression. In fact, positive studies incorrectly utilized menstruation as a surrogate of fertility and did not report on the regularity of cycles. The most common manifestation of impending ovarian failure is irregular menstruation, not amenorrhea. None of the randomized studies used placebo or blinding, leaving the door open to possibly interpreting any menstrual bleeding as a sign of normalcy in the GnRHa treatment group. Likewise, if the subject and the researchers know that the patient did not receive GnRHa, they may have a more pessimistic take on irregular or scant menstruation. Many studies did not even control for tamoxifen use, which can also alter menstruation. Moreover no study, including those which suggested some benefit to menstruation, conclusively showed any benefit to fertility. In the study by Moore et al., when the pregnancy intent was considered, there was no difference in conception rates.7

In a recent meta-analysis that included 10 eligible trials in 907 women with the primary outcome defined as the proportion of women with resumed ovarian function at the longest follow-up after the end of chemotherapy, GnRHa co-treatment did not favor ovarian function resumption (68.4% in GnRHa versus 59.9% in chemotherapy-alone; risk ratio [RR] 1.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.99–1.27).10 The results were not affected by type of malignancy (p=0.31), age (p=0.14), and GnRHa type (p=0.44). GnRHa was also not protective based on follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) (mean difference −2.63, 95% CI −7.33 to 2.07), antral folicle count (AFC) (mean difference 1.66, 95% CI −0.69 to 4.01), or anti-Mullerian-hormone (AMH) (mean difference 0.31, 95% CI −0.41 to 1.03). The spontaneous conception probability was also similar (RR 1.63, 95% CI 0.94–2.82).5

This should not come as a surprise because chemotherapy induces ovarian failure by causing double strand DNA breaks and apoptotic death in primordial follicles11 which are not hormone sensitive.12 Hence the idea that suppression of FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) hormones by GnRHa would somehow protect primordial follicle oocytes does not have any scientific rationale. In our opinion, GnRHa should not be offered as an effective measure of fertility preservation; it has already been dropped for men.

Finally, the feasibility of ovarian stimulation in women with estrogensensitive cancer continues to improve. To minimize the estrogen exposure during ovarian stimulation for oocyte and embryo cryopreservation, we developed a concurrent aromatase inhibitor and gonadotropin treatment protocol.13 In two recent studies, we showed that over 50% of women who preserved embryos with this method were able to have at least one child14 and that long term cancer recurrence rates were not increased regardless of the BRCA status or whether the ovarian stimulation took place before or after surgery.15 In addition, the flexibility of ovarian stimulation protocols have also increased with the introduction of random start stimulation protocols.16 Studies have now shown that the efficiency of an oocyte retrieval is the same regardless of when the stimulation is started in relation to the onset of menstrual period.16 As a result, an oocyte embryo cryopreservation treatment can be initiated immediately and completed in as little as a 2 weeks’ time.

In conclusion, options for fertility preservation have significantly improved for cancer patients (Figure 1). Embryo, oocyte, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation are all proving to be effective strategies. However, there are no proven medical means of preserving fertility, including the utility of GnRH analogs. Depending on the age of the patient, available time, cancer diagnosis, and desired outcomes, fertility preservation experts can tailor a strategy that best suits each woman with cancer.