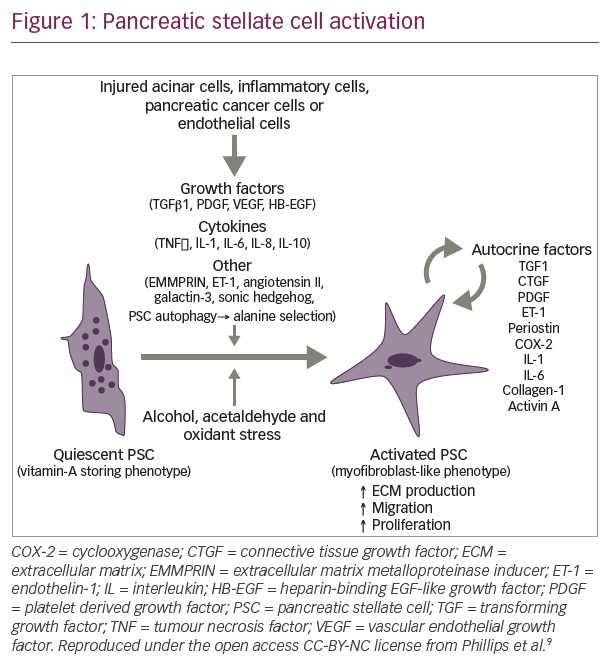

Pancreatic cancer remains a common disease. It ranks as the fourth and fifth leading cause of cancer deaths in the US and Australia, respectively. It was predicted that 37,000 new cases would be diagnosed in the US in 2007 and that more than 33,000 people would die from their disease. Five-year survival is less than 5%.1,2 Despite many advances in treatment, median survival remains the lowest of any advanced cancer. With no treatment, metastatic pancreatic cancer has a median survival of three to five months and locally advanced disease six to 10 months, and with surgery alone 11–15 months.3 The most common histology is that of ductal adenocarcinomas, which usually occur in the head of the pancreas.4 Age of diagnosis is typically between 60 and 80 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.35: 1.0.5 The aim of systemic treatment in any cancer is to cure the disease, prolong survival by three to four months, or relieve symptoms more than occasionally.6 Despite the relatively poor outcomes in treatment of pancreatic cancer, treatment is warranted if we can achieve one of these goals. A number of genetic changes have been identified during the process of malignant transformation. These include both inactivation of tumor suppressor genes such as p16 and activation of oncogenes such as kRAS,7 together with activation of growth promoters such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGRF) and its ligands. Identification of these factors and their downstream pathways has led to an increasing repertoire of targets for therapeutic intervention,7–9 many of which are already being investigated in clinical trials or used in practice in addition to surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. A better understanding of molecular pathogenesis in pancreatic cancer allows for improved therapeutic targets.

Management of Localized Disease

Surgical resection is the only effective therapy that can offer the chance of a long-term cure. However, the late presentation of the disease means that surgical resection is possible in only approximately 10% of patients.1,10 The surgical approach is a radical pancreatic duodenectomy. The first operations to remove the duodenum and part of the pancreas were performed by Kausch in 1912 and Whipple in 1934, respectively. Resection involves partial resection of the pancreas and duodenum and may include a partial gastrectomy.11 The aim of surgery is to have no macroscopic disease and clear margins.6,7

In one large review,12 only 6.4% of patients were eligible for surgical resection, and five-year survival was only 3.5% in those who had undergone surgical resection. This equates to 0.4% of all comers with pancreatic cancer. In other studies, five-year survival rates range between 0.413 and 8% with surgery alone.14 Even those eligible for surgery are often overlooked, despite no identifiable contraindications. It has been estimated that 38.2% of patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancer who were eligible for pancreatectomy were not offered surgery. This figure accounts for patients who did not undergo surgery due to severe comorbidities, advanced age, or patient refusal.15 Patient prognosis is currently based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, which is purely based on the tumor, node, metastases (TNM) staging system. However, there are many other factors that can predict survival,16,17 including resection margin, tumor grade, size and location, nodal status, performance status, and age.14,18,19 Adjuvant Therapy

Experience from other cancers, including breast, colon and lung cancer, has shown the benefit of systemic therapy in addition to surgery. Recent trials have established that adjuvant therapy is indicated in resected pancreatic cancers.

The choice of chemotherapy alone or combined with radiation therapy remains controversial and to some degree appears to be dictated by whether treatment is received in Europe or the US. In Australia, most patients are treated with adjuvant chemotherapy if they have positive margins or positive nodes and are of good performance status. In the US and Canada, chemoradiation has become the standard of care in the adjuvant setting based on a small study (n=43) by the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group that compared a split course of chemoradiation with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) versus observation followed by maintenance chemotherapy.19 Median survival was significantly longer in the chemoradiation group than in the surgery alone group (20 versus 11 months). The European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC) assessed the relative roles of chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy in a two-by-two factorial designed study (observation, chemoradiotherapy alone, chemotherapy alone, or both). Patients were randomly assigned to adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, a split course of two series of 20Gy in 10 fractions over two weeks with 500mg/m2 5-FU intravenously on days one to three every two weeks or intravenous 5-FU 425mg/m2 on days one to five every four weeks. Overall results showed no benefit for adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (median survival 15.5 versus 16.1 months; p=0.24); however, there was evidence of a survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy (median survival 19.7 versus 14.0 months; p=0.0005).14 Five-year survival was also superior in those receiving chemotherapy: 20% compared with 8% in those who did not. It must be noted that there have been criticisms of the methodology employed for radiation and the trial was not powered to detect numerous interactions between treatments. However, based on this trial, European oncologists have deemed that there is no role for radiotherapy in the adjuvant setting.

Further trials have attempted to evaluate the best chemotherapy regime. Gemcitabine has been shown to be superior to 5-FU in the metastatic setting, and so was recently trialed in the adjuvant population. Oettle et al. randomized 368 patients to receive six cycles of gemcitabine post-surgical resection versus observation alone. They showed an improvement in median disease-free survival of 13.4 versus 6.9 months (p<0.001); however, to date there has been only a nonsignificant trend for improved OS in favor of gemcitabine (p=0.06). The disease-free survival rates at one, two, three, and five years were 58, 30.5, 23.5, and 16.5%, respectively, in the gemcitabine group and 31, 14.5, 7.5, and 5.5%, respectively, in the control group.20 Preliminary results of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 9704, a large randomized US Gastrointestinal Intergroup trial, compared gemcitabine with 5-FU given three weeks before and 12 weeks after chemoradiation with sensitizing 5-FU in 442 patients in the adjuvant setting. It showed that in the 381 patients with pancreatic head tumors only, gemcitabine significantly improved OS (median survival 20.6 versus 16.9 months, three-year survival 32 versus 21%; p=0.03). However, when analysis included patients with either body or tail tumors (n=442), no significant difference in survival was found (p=0.20).21

A meta-analysis of pooled data from Norwegian, Japanese, and European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC) studies showed that adjuvant chemotherapy significantly reduced the risk for death compared with no chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.64–0.90; p=0.001). The difference in survival was 19 months with chemotherapy and 13.5 months without. In comparison, adjuvant chemoradiation showed no difference in survival, but a sub-group analysis did show a significant difference in the effect of chemoradiation in patients with a positive resection margin (p=0.04).22

Pre-operative Chemoradiation

Neoadjuvant treatment is still a controversial area and there is not enough information at this time to make an appropriate recommendation.

Management of Locally Advanced Disease

Treatment options in locally advanced disease include systemic therapy, palliative surgical bypass or biliary stent placement, radiation with or without chemotherapy, or palliation of pain with celiac nerve blocks. Tumors are deemed to be resectable in the absence of extrapancreatic disease if there is no evidence of tumor encasement of the superior mesenteric artery or celiac axis, defined by the presence of a normal fat plane between the tumor and these arterial structures, and a patent superior mesenteric–portal vein confluence.23 Unfortunately, many patients have unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer without evidence of peritoneal or systemic spread at time of diagnosis. The slightly better outcomes of this subset have raised the question of whether they should be treated differently from those with metastatic disease. The median survival in these patients is six to nine months as opposed to three to four months for metastatic disease.

The role of chemoradiation was first canvassed in 1969 by the Mayo Clinic using 5-FU-based chemoradiation in a randomized controlled trial involving 64 patients, in which moderate-dose radiation given over four weeks in combination with 5-FU given as a bolus over the first three days was compared with radiation therapy alone. The survival advantage in those patients treated with chemoradiation was 10.4 months compared with 6.3 months in the radiation alone arm (p<0.05).24 A subsequent study lent support to this, with improved one-year survival of 40 versus 10% and a similar OS of 10 months in the combined treatment group. This study used a split course of radiotherapy, which was associated with lower toxicities.25

Since the use of gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic disease has become standard of care, its use has also been trialed in the locally advanced subgroup of pancreatic cancers. The Cancer and Leukaemi Group B conducted a phase II randomized controlled trial (CALGB 89805) of concurrent radiotherapy with 50.4Gy and low-dose weekly gemcitabine 40mg/m2 twice weekly, but showed disappointing results, with a median survival rate of only 8.2 months; however, those with a performance status of 0 did better, with a median survival of 13.7 months.26 Another study from the Hoosier Oncology Group (HOG) has shown more promising results, with a 31.1% one-year survival rate and a more favorable side-effect profile in patients treated with weekly gemcitabine 600mg/m2 and concurrent radiotherapy (50.4Gy).27 There have also been advances with 3D conformal radiotherapy, which allows a reduction of radiation fields and an optimization of radiationsensitizing chemotherapy.28 An Australian study utilizing gemcitabine and conformal radiation has shown promising improvements in both local control and survival. Treatment was with gemcitabine chemotherapy given weekly for three weeks followed by a one-week rest, after which patients underwent six weeks of radiotherapy with continuous-infusion 5-FU and, following a four-week break, a further three cycles of gemcitabine (days one, eight, and 15). 3D conformal radiotherapy using computed tomography (CT) planning allowed a higher dose to be delivered to the tumor while sparing the healthy tissue. At the end of treatment, 7.3% of patients had a complete response and 4.9% a partial response. Median survival time was 11.7 months and survival rates at one and two years were 46.3 and 9.8%, respectively. There were acceptable acute and late toxicities.29

There has also been some investigation with paclitaxel-based chemoradiation, and ongoing trials are evaluating this further. The RTOG trial demonstrated a median survival of 11.2 months (95% CI 10.1–12.3) with estimated one- and two-year survival of 43 and 13%, respectively.30 Other recent studies have replaced 5-FU with gemcitabine during radiation without compromising safety.31

The optimal approach in this subgroup remains controversial. Huguet et al. evaluated 181 patients who had already received three months of chemotherapy and who were randomized to chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone. Median progression-free survival (PFS) times were 10.8 and 7.4 months, respectively (p=0.005), and median OS times were 15 and 11.7 months, respectively (p=0.0009). This led to the conclusion that after control of disease by initial chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy could significantly improve survival in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer compared with chemotherapy alone.31 A recent systemic review and meta-analysis attempted to investigate this conclusion, specifically addressing the use of radiotherapeutic approaches in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. It compared: chemoradiation followed by chemotherapy versus best supportive care; radiotherapy versus chemoradiation; radiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy; chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy; and 5-FU-based chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy versus another-agentbased chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy. Almost 800 patients were included in the analyses across 11 trials. Survival with chemoradiation was better compared with radiotherapy alone (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51–0.94). Chemoradiation followed by chemotherapy showed no survival advantage over chemotherapy alone (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.32–1.95). However, the wide CIs and heterogeneity between studies using different chemotherapy agents and different radiotherapy regimes could partly account for this difference.

There were no trials comparing chemoradiation alone or radiation alone versus best supportive care and only a single trial showing the superiority of chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy over radiotherapy alone.33 A recent randomized trial showed that intensive combination chemotherapy and radiation has the potential to be harmful in this setting, and suggests that care in choice of regimen is a very important part of evaluating the true role of radiation.34 Prospective phase III studies are ongoing to further evaluate this strategy.

Metastatic Disease

Supportive care has a major role in managing symptoms, with an important focus on good analgesic and anabolic agents, including megestrol acetate, dexamethasone, and pancreatic supplements.35 However, recent meta-analyses have shown a survival benefit for chemotherapy compared with best supportive care.36

Until 1997, 5-FU was the standard of care for advanced pancreatic cancer, then a pivotal study compared gemcitabine with 5-FU and showed a clinical response in 23.8% of those treated with gemcitabine compared with 4.8% of those treated with 5-FU (p=0.0022), with median survival of 5.7 and 4.2 months, respectively (p=0.0025).37 Survival rates at 12 months were 18% for gemcitabine patients and 2% for those treated with 5-FU. Significant improvements in clinical benefit included pain relief and improved performance status. As a result, gemcitabine became the standard of care for metastatic disease. Median survival for gemcitabine regimes has consistently been 5.4–5.6 months, with a one-year survival rate of 16–19%.38 Subsequently, there have been many phase III studies looking at the use of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer. No single agent has shown superiority over gemcitabine in a randomized phase III trial. There have also been numerous studies comparing combination chemotherapy regimes including gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone. The Cochrane review showed increased response rates in some of the combinations, but this did not equate to an OS advantage. Cisplatin and gemcitabine combination regimes were associated with a survival benefit at six months, but this did not extend to 12 months. Quality of life data showed a mixed response. The conclusion of the Cochrane metaanalyses was that gemcitabine alone was an acceptable palliative treatment for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.36

A more recent meta-analysis by Sultana et al.38 compared chemotherapy versus best supportive care, 5-FU versus 5-FU combination chemotherapy, gemcitabine versus 5-FU, and gemcitabine versus gemcitabine combination chemotherapy. It based its conclusions on a more robust end-point of HRs rather than relative risk or odds ratio. While Sultana’s meta-analysis supported the findings of the earlier review papers that chemotherapy was superior to best supportive care, its conclusions on the appropriate chemotherapy regime differed. It found that 5-FU combination regimes did not result in better survival compared with single-agent 5-FU and that there was insufficient evidence of a survival difference between gemcitabine and 5-FU. This latter conclusion is perhaps a little more difficult to interpret given the fact there were only two trials analyzed and there was significant heterogeneity with wide CIs.What is perhaps more significant is the finding that combination therapy with gemcitabine was superior to single-agent gemcitabine (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85–0.97). Sub-group analysis found evidence to support combinations with cisplatin or capecitabine, but not with irinotecan or 5-FU; the inclusion of studies not previously reviewed in earlier meta-analyses could help to explain this. The platinum results have led to several studies of new-generation platinum agents such as oxaliplatin. In a randomized phase III study, Louvet et al. assigned patients to either gemox (gemcitabine 1,000mg/m2 on day one and oxaliplatin 100mg/m2 on day two every two weeks) or gemcitabine 1,000mg/m2 weekly alone. Gemox showed a superior response rate, PFS, and clinical benefit; however, OS did not reach statistical significance. Given that the landmark Burris trial that led to gemcitabine becoming the standard of care was based on clinical benefit, this suggests that further studies with gemox are warranted.39

Of note are two capecitabine studies. A Swiss study compared gemcitabine and capecitabine versus gemcitabine alone. While there was no overall difference in survival rates, in subsequent sub-group analysis, with its acknowledged limitations, patients with a good performance status (Karnofsky performance status [KPS] 90–100) had a significant prolongation of median survival of 10.1 versus 7.4 months (p=0.014).40 No added gain in terms of quality of life or clinical benefit was seen for the combination.41 A larger UK study has to date reported only its interim analysis. The investigators used gemcitabine 1,000mg/m2 weekly on days one, eight, and 15 every four weeks in combination with capecitabine 1,660mg/m2/day for 21 days every four weeks, and showed significantly improved OS with the combination regime over gemcitabine alone (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98; p=0.026). After adjusting for baseline stratification factors, the survival advantage remained (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63–0.95; p=0.014). Median survival for gemcitabine and gemcitabine–capecitabine was six and 7.4 months, respectively, and one-year survival rates were 19 and 26%, respectively.42 The final results of this trial are yet to be published. An additional randomized phase II study of capecitabine combinations showed both efficacy and safety for both oxaliplatin and gemcitabine, but no clear priority for any combination.43

More recently, mature information has established a role for secondline chemotherapy for appropriately selected patients. The combination of capecitabine and erlotinib showed some modest benefit, with a response rate of only 10% but a median survival of 6.5 months.44 This was followed by preliminary results of a randomized trial of 5-FU and leucovorin versus 5-FU and oxaliplatin, with PFS of 13 versus nine weeks and an OS benefit of 26 versus 13 weeks.45 Targeted therapies have also been trialed in pancreatic cancer, although to date these have not been included in any meta-analyses.46–50Agents trialed in phase III trials include ras-farnesyltransferase inhibitors (tipifarnib), matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (marimastat, Bay 12–9566), and a gastrin vaccine, none of which showed increased benefit from the addition of a targeted agent to gemcitabine. More recently, a promising result was shown with erlotinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine was superior to single-agent gemcitabine in terms of OS (HR 0.81; p=0.025) and PFS (HR 0.76; p= 0.003 ).51 There was also improved one-year survival of 24 versus 17% in favor of the combined regime. Of note, there was increased toxicity associated with erlotinib, but this was usually tolerable and in the form of a skin rash; importantly, those who demonstrated this toxicity were associated with a better outcome. Prospective predictive factors to identify those most likely to benefit will maximize cost-efficacy and increase the utilization of such therapies. Recently, a large phase III study utilizing a monoclonal antibody to the EGFR added to gemcitabine in over 700 patients showed no differences in OS or PFS between treatment arms, although time to treatment failure was significantly prolonged with combination therapy.52 There have also been disappointing results with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab. The CALGB 80303 study compared gemcitabine plus bevacizumab versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and showed no significant difference in treatment response or survival outcomes (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.65-1.23; p=0.36 in favor of control).53 Another study comparing gemcitabine in combination with erlotinib versus the same combination plus bevacizumab showed PFS increase of one month (p=0.0002), but no increase in OS.54 A recent randomized phase II study utilizing a new vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor—axitinib—has shown important improvement over gemcitabine alone, and may represent a new direction if the current phase III trial is also positive.55

Conclusion

We concluded that chemotherapy has a role in advanced disease. Gemcitabine provides both local benefit and modest survival gains and is the optimal single agent. In those with adequate performance status, combination with either platinum agents or capecitabine has modest superiority to gemcitabine alone. Adjuvant therapy is an important advance over surgery alone. The role of chemoradiation in locally advanced disease remains uncertain, but requires investigation and support. However, despite improvements in treatment, median survival in pancreatic cancer is poor, with treatments making only a modest difference in survival. Ongoing research is needed, particularly in genomic profiling, biomarker identification, and optimal use of targeted therapies, to select those patients who will derive maximal benefit. ■