A satellite symposium, chaired by Eric Van Cutsem and Josep Tabernero, was held on the 3rd July 2013 at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 15th World Congress of Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona to discuss the oral fluoropyrimidine S-1. Systemic chemotherapy is the standard treatment for unresectable, advanced or recurrent gastrointestinal (GI) cancers. The goal of therapy is to provide palliation and prolong survival. Various randomised trials comparing 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) alone and the combination of 5-FU and other drugs have evaluated treatment options. Oral fluoropyrimidines have been developed as replacements for infusional 5-FU therapy, and have become the mainstay of gastric cancer (GC) therapy in Japan. They include capecitabine (Xeloda®, Roche) and S-1 (Teysuno®, Nordic Pharma). However, capecitabine is associated with dose-limiting toxicities, including hand-foot syndrome (HFS).1

S-1 is a combination of three pharmacological compounds: tegafur, gimeracil and oteracil potassium. The application of S-1 for GC has been delayed in Western countries, as the pharmacokinetics of tegafur is affected by polymorphisms in cytochrome P-450 2A6, and consequently 5-FU concentrations in the plasma are more likely to be elevated in patients from Western countries. In 2011, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, a division of the European Medicines Agency, issued an opinion recommending the approval of S-1 for treatment in adults with advanced GC (aGC) when given in combination with cisplatin that led to European marketing authorisation. The aim of the symposium was to outline the history of S-1 development for GI cancer chemotherapy, considering the ethnic differences between Western and Asian countries, and review clinical trial data in support of its use in various GI applications.

Gérard Milano

Head, Oncopharmacology Laboratory – UNS EA 3836, Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice, France

Dr Milano emphasised that variability in patient response to drug therapy is an inherent drawback of anticancer chemotherapy. This variability originates not only from patent factors (such as physiology and genetics), but also the tumour tissue. These, together with the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drug, result in variability in response and toxicity.

Improvement of 5-FU Formulation Due to a Greater Understanding of 5-FU Mode of Action

Pharmacogenomics research is yielding molecular diagnostic tools that can be used to individual the selection of medications and their doses. Two genomes are important: the patient’s inherited genome variation and the tumour’s inherited genome variation plus acquired genome variation. Additional acquired genome variations may occur in metastatic or recurrent tumour cells that influence drug response and treatment outcomes. A comprehensive pharmacogenomic strategy should encompass multiple mechanisms of genome variation.2

Fluoropyrimidines have formed the mainstay of GI cancer therapy for many years. Prior to 1980, 5-FU was primarily used as monotherapy. In the 1990s it began to be used in combination with newer cytotoxic therapies such as irinotecan and oxaliplatin, and after 2000, targeted therapies were added to combined treatment regimens, resulting in positive trends in median survival rates, which now exceed 20 months.3 The continued evolution of 5-FU has led to the development of oral forms of the drug. Resistance and toxicity have been significant limitations to the clinical use of 5-FU. Increased understanding of the mechanism of action of 5-FU has led to the development of strategies to overcome these limitations. 5-FU is regulated via a complex network of anabolic and catabolic genes. The cytotoxicity of 5-FU is a result of anabolism to nucleotides. The 5-FU active metabolite fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate (FdUMP) binds to the nucleotidebinding site of thymidine synthase (TS) and forms a stable ternary complex with TS and CH2THF, blocking the conversion of deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP). This results in deoxynucleotide (dNTP) imbalances and increased levels of deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP), both of which cause DNA damage.4

5-FU Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism

Pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated that only 20 % of clinically administered 5-FU is inactivated and eliminated through the anabolic pathway. The remainder undergoes catabolism by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), which is found in liver tissue and enterocytes. Variability in DPD activity in the normal population accounts for the observed differences in the pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of 5-FU;5 a deficiency of DPD has been recognised as an important risk factor, predisposing patients to the development of severe 5-FU-associated toxicity.6 Therefore, reducing the catabolism of 5-FU by DPD should increase the availability of the drug.

The pivotal role of DPD in the metabolism of 5-FU presents a major challenge to clinical oncologists. Available options to circumvent the DPD hurdle include using 5-FU prodrugs such as capecitabine (Xeloda®), or to inhibit DPD. Among the oralfluoropyrimidines recently developed, two were DPD inhibitors: EU-5-FU (eniluracil//FU) and UFT (tegaflur [ftorafur] + uracil at a 1:4 molar ratio; the excess uracil competes with 5-FU for DPD), but these have not demonstrated significant efficacy advantages in clinical trials (please see Box for definitions of trials discussed in this article).7–9 Capecitabine is sequentially converted to 5-FU by three enzymes located in the liver and in tumours.10 After oral administration, capecitabine is rapidly and extensively absorbed from the GI tract and has a relatively short elimination half-life.11

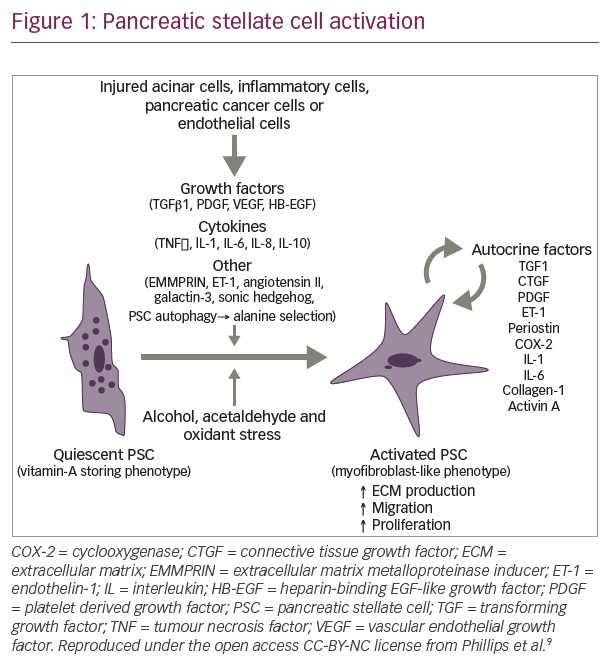

S-1 contains tegaflur, gimeracil (5 chloro 2,4 dihydroxypyridine – CDHP), a strong DPD inhibitor that prolongs the half-life of 5-FU, and oteracil (OXO, potassium oxonate), OXO inhibits the phosphorylation of 5-FU to fluorouridine monophosphate, an active intermediary metabolite of 5-FU, by orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (OPRT) in the GI tract, thereby reducing GI-related toxicity of 5-FU. Tegafur [R,S-1- 1(tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-5-FU] is a prodrug that is mainly converted by cytochrome P450 2A6 (CYP2A6) to 5-FU.12 CYP2A6 shows large interindividual and interethnic variations in its expression levels and conversion activities, which are mainly attributed to CYP2A6 genetic polymorphisms, and are more common in Asian than Caucasian populations. The higher efficacy of CYP2A6 results in the more rapid conversion of tegafur to 5-FU in Caucasian subjects, who achieve a higher area under the curve of 5-FU than Asians, and therefore have a different optimal dosage level.13 The CYP2A6 genotype correlated with the treatment efficacy of S-1-based chemotherapy in previously untreated metastatic GC (mGC) patients; patients with fewer variant alleles had significantly better response rates.14

The S-1 formulation of 5-FU may also confer a pharmacokinetic advantage. A pharmacokinetic study compared continuous infusion of 5-FU with oral administration. Individual 5-FU concentrations in the blood during continuous infusion were highly variable, whereas those after oral administration were reproducible.15 In a comparison of 5-FU pharmacokinetics in patients receiving continuous 5-FU infusion and oral UFT, the maximum 5-FU concentrations generated from oral UFT were higher than the steady-state levels during continuous infusion. A further study investigated the impact of DPD inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of 5-FU by comparing the pharmacokinetic profile of S-1 to that of tegafur alone. Exposure to 5-FU was significantly greater following S-1 administration compared with tegafur administration.16

There is a need to optimise the dosage and scheduling of oral fluoropyrimidines on the basis of their pharmacological characteristics. In addition to CYP2A6, tumoural thymidine phosphorylase plays a critical role in 5-FU activity by being involved in neoangiogenesis and by activating 5-FU prodrugs at the target site.17 In studies of capecitabine, predictors of resistance include high DPD expression18,19 and a high TP/ DPD ratio.20 In studies of S-1, predictive factors for resistance include TS, DPD and OPRT.21 In conclusion, capecitabine and S-1 represent a successful shift from IV to oral administration in GI oncology and pharmacological studies have suggested a potential role for personalised treatment, though further research is required to optimise treatment and the impact of pharmacogenetics on drug activity should be further investigated. The multistep modulation of S-1 may improve its efficacy and safety ratio and represents a significant advance in the treatment of GI cancer (see Figure 1).

Katsuhiko Uesaka

Chief, Division of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, Shizuoka Cancer Center, Shizuoka, Japan

Dr Uesaka gave details of a randomised phase III open-label multicentre study of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine (GEM) versus S-1 in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (PC) – the Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC) 01. Data from this study were also presented at the 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) GI Cancers symposium and the 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting.22,23 Dr Uesaka started by outlining the background to S-1 and PC. S-1 is now approved in 38 countries: 30 in Europe, where it is approved for the treatment of GC and eight in Asia. In Japan it is also used in the treatment of colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, inoperable or recurring breast cancer, biliary tract cancer and PC.

GEM has been the current standard treatment as adjuvant chemotherapy for resected PC.24,25 However, in the GEST phase III clinical trial of patients with locally advanced or metastatic PC, monotherapy with S-1 demonstrated non-inferiority to GEM in overall survival (OS), with good tolerability, and presents a convenient oral alternative for unresectable PC,26 leading to its investigation for use in the adjuvant setting.

The objective of the JASPAC 01 study was to assess non-inferiority of S-1 to GEM as adjuvant chemotherapy for resected PC. The primary endpoint was OS. Secondary endpoints included relapse-free survival (RFS), adverse events (AEs) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Within 10 weeks following curative resection, patients (n=385) were randomly assigned to GEM (n=193) or S-1 (n=192). Eligibility criteria included histologically proven invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas; Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) stage II or lower, or stage III with combined resection of the coeliac artery; histologically confirmed R0 or R1 residual disease; peritoneal lavage cytology showing negativity for cancer cells; age >20 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; no previous chemo- or radiotherapy within 3 years; enrolment within 10 weeks after pancreatectomy; and adequate renal, hepatic and bone marrow functions. More than 90 % of patients in both groups were diagnosed as stage II, and approximately 70 % in both groups assessed as ECOG performance status 0 with the remainder performance status 1. Approximately 86% of primary tumours in both groups were stage T3.

An interim analysis of trial data found that patients who received S-1 had a 44 % lower risk of death than patients who received GEM.22,23 At 2 years, the OS in the S-1 treatment group was 70 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 63–76 %) whereas the OS in the GEM group was 53 % (95 % CI 46–60 %). Subgroup analysis favoured S-1 in all parameters. S-1 was also well tolerated; 42% of the GEM group and 28% of the S-1 group discontinued the protocol treatment. Reasons for discontinuation included toxicity (25 % GEM and 21 % S-1) and recurrence (14% GEM and 5 % S-1). The very low rate of discontinuation owing to recurrence in the S-1 group should be highlighted. The median relative dose intensity was 85 % with GEM versus 98 % with S-1. S-1 also demonstrated a favourable safety profile compared with GEM, with a significant and substantial reduction of haematological and hepatic toxicities associated with S-1 treatment. Stomatitis and diarrhoea were more commonly observed following treatment with S-1 but the incidence of each was low (<5 %). The number of relapses was lower in the S-1 group compared with GEM (59 % versus 75 %). After relapse, crossover treatments were performed: 55 % of the GEM group crossed to S-1 treatment and 57 % of the S-1 group crossed over to GEM treatment. Multivariate analysis showed that T stage and residual disease status were independent prognostic factors for survival. Treatment with S1 may also contribute to a better QoL; the EuroQol (EQ-5D) utility index increased with time in the S-1 group.

In summary, although JASPAC 01 was a non-inferiority trial, adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 showed considerable superiority to GEM on OS and RFS in patients with resected PC. The treatment was well tolerated in an adjuvant setting and as a result, the guidelines committee in Japan are changing their recommendations and S-1 is considered the new standard treatment for resected pancreatic cancer patients in Japan. The findings of this study are not immediately applicable to non-Asian populations, but it is intended that studies will be conducted in Europe and the US among Caucasian patients, with adjustment of the S-1 dose. There is also a need for a multinational trial that is powered for superiority

Salah-Eddin Al-Batran

Director, Institute of Clinical Research, Krankenhaus Nordwest, UCT – University Cancer Center, Frankfurt, Germany

Dr Al-Batran considered the current prognosis for GC, which depends on the clinical staging of the tumour. Most GCs in Europe are diagnosed at stage III, at which stage the wall of the stomach is no longer sharp, and there is lymph node involvement. The prognosis differs between Western and Asian populations: in the former, survival rates are around 25 % at 5 years. The mainstay of treatment is curative surgery; however, many patients have disease recurrence after surgery, therefore adjuvant and perioperative chemotherapeutic strategies have been developed.

Perspectives in Adjuvant Therapy for Gastric Cancer

Two clinical trials: the ACCORD27 and MAGIC,28 demonstrated that perioperative chemotherapy significantly improved progression-freesurvival (PFS) and OS in GC compared with surgery alone. This has become the most important clinical strategy in Europe; adjuvant chemotherapy is employed to a lesser extent. Individual clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy have yielded negative results although a meta-analysis showed modest improvements in efficacy: adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a statistically significant benefit in terms of OS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.82); and five-year OS increased from 49.6 % to 55.3 % with chemotherapy.29 This is in marked contrast to Asian data, which show substantial benefits for adjuvant chemotherapy compared with surgeryalone.30,31 The Adjuvant Chemotherapy Trial of S-1 For Gastric Cancer (ACTS-GC) phase III trial in Japan randomised patients (n=1,059) withresected stage II and III GC to S-1 monotherapy or surgery only, and found that 3-year OS was 80.1 % (S-1) versus 70.1 % (surgery only).30,32

Benefit of Triplet Regimen in Advanced Gastric Cancer for Patients Able to Withstand Increased Toxicity

In inoperable or metastatic GC, chemotherapy prolongs OS in the firstline setting. Furthermore, chemotherapy can preserve and even improve QoL in some patients. 5-FU is the mainstay of GC therapy. The following combined regimens are commonly used in Europe: CF (cisplatin + 5-FU), DCF (docetaxel + cisplatin + 5-FU), PLF (leucovorin [LV], cisplatin + 5-FU, FLO (5-FU + LV + oxaliplatin) and FLOT (5-FU + LV + oxaliplatin docetaxel), ECF (epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-FU), ECX (epirubicin, cisplatin + capecitabine) and EOX (epirubicin, oxaliplatin and capecitabine). Recent advances in research have helped to optimise therapeutic decisionmaking.It has been found that oxaliplatin is as effective as cisplatin, with significantly reduced toxicity.33,34 Capecitabine has also been shown to be as effective as 5-FU.34,35 Triplet therapy may also be preferable to doublet: the addition of docetaxel to 5-FU has been shown to improve outcomes in aGC.36 Adding docetaxel to CF significantly improved response rate (RR), time to progression (TTP) and OS but resulted in increased toxicity: febrile neutropenia, diarrhoea and neuropathy. To reduce this toxicity, a modified DCF regime has been suggested.37

Doublet Regimen with S-1 Plus Cisplatin

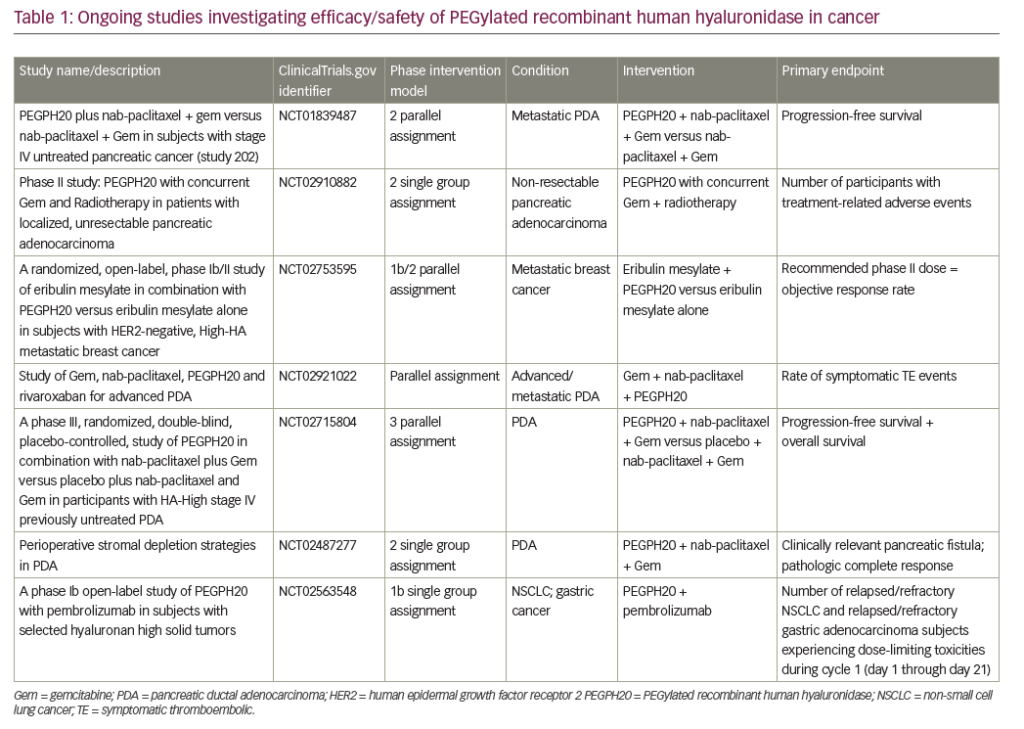

The development of S-1 has increased the therapeutic options for GC: results of clinical trials of S-1 are summarised in Table 1. A Japanese phase III open-label, multicentre clinical trial in 704 Japanese patients with mGC demonstrated that S-1 is non-inferior to 5-FU.38 in view of the convenience of an oral administration, S-1 could replace IV 5-FU for the treatment of unresectable or recurrent GC. In the Caucasian population, the FLAGS study was a phase III open-label, multicentre study in 1,053 patients with locally advanced or metastatic GC, including cancer of the gastro-oesophageal junction.39 Cisplatin/S-1 (CS) proved non-inferior to CF, with a non-significant trend towards superiority (see Figure 2), and subgroup analysis demonstrated that S1 was clearly superior in certain patient subgroups. Furthermore, S-1 resulted in a significantly improved safety profile: it was associated with fewer haematological AEs (see Figure 3).40 The study concluded that S-1 can replace 5-FU in GC therapy. European marketing authorisation was based on these data.

Colorectal Cancer – First-line Treatment with SOX + Bevacizumab Versus FOLFOX Alone

Dr Al-Batran discussed the JASPAC 01 trial and then moved on to colorectal cancer (CRC), for which the mainstay of therapy has been combined regimens with associated toxicities. FOLFOX (folinic acid, FU and oxaliplatin) has been linked with polyneuropathy; FOLFIRI (folinic acid, FU and irinotecan) is associated with anaemia, hair loss and fatigue.41 S-1 may provide an alternative, more tolerable treatment option. The results of the phase III SOFT study were recently presented at ASCO. As a first-line treatment for mCRC, S-1 in combination with oxaliplatin (SOX) + bevacizumab (Bev) was compared with a standard treatment of FOLFOX + Bev in patients with mCRC.42 As a first-line treatment, SOX + Bev was demonstrated to be noninferior to FOLFOX in terms of PFS. The regimen was well tolerated, with an AE profile similar to FOLFOX + Bev. It was concluded that SOX + Bev can replace FOLFOX + Bev as a first-line treatment for mCRC.

Dr Al-Batran concluded by stating that S-1 is at least non-inferior to 5-FU for advanced gastric, pancreatic and colon cancer. It provides an oral alternative to IV 5-FU and is better tolerated, with no reported association with HFS. Recent findings suggest outstanding efficacy in the adjuvant setting in pancreatic cancer. Consequently, S1 will play an important role in the future of GI cancer treatment in Europe and could be combined with targeted therapy.

Per Pfeiffer

Professor in Clinical Oncology, Department of Oncology, OUH, Odense, Denmark Institute of Clinical Research, USD, Odense, Denmark

Dr Pfeiffer gave an overview of the numerous combinations of 5-FU and platinum salts that can be employed in the treatment of GC in Denmark. These may include docetaxel or the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab. Accepted combination regiments include CF, CS (cisplatin + S-1), EOX, EOF (epirubicin + oxaliplatin + fluorouracil) and DOF (docetaxel + oxaliplatin + 5-FU), and regional variations exist in the standard of care.36,43–45

In Advanced Gastric Cancer, S-1 Plus Oxaliplatin has Become a New Standard of Care for First-line Treatment in Asia

The presentation next focused on some major clinical trials involving S-1 in GC (see Table 1). The SPIRITS trial (n=298) compared treatment with S-1 plus cisplatin to treatment with S-1 alone in patients with aGC.

The combined treatment group had a significant increase in response rate (54 % versus 31 %), PFS (6.0 months versus 4.0 months) and OS (13 months versus 11 months) compared with S-1 alone. S-1 plus cisplatin therefore may become a standard first-line treatment for patients with aGC.46

The large START clinical trial (n=635) compared the combination of S-1 and docetaxel with S-1 monotherapy. The median OS was 12.5 months in the combination therapy group compared to 10.8 months in patients who received S-1 alone. The combined treatment group also showed significant increase in response rate (39 % versus 27 %) and PFS (5.3 months versus 4.2 months) compared with S-1 alone, but the combined regimen was associated with an increased incidence of haematological toxicities.47 Ongoing studies in Japan (JCOG1013) aim to compare CS with DCS (docetaxel, cisplatin, S-1) as first-line therapy for aGC. A study comparing SO (S1 + oxaliplatin) and SC (S-1 + cisplatin) treatment regimens in patients with aGC found no efficacy difference between the two, with benefits for SO in terms of outpatient-based treatment.48 Therefore, SO may become a new standard regimen in Asia for the firstline treatment of aGC.

Optimising the Triplet Regimen for Advanced Gastric Cancer in Europe

In Europe, ECF has long been the standard regimen in many clinics, following two clinical trials that demonstrated superior survival and QoL.49,50 However, researchers wanted to develop a more tolerable regimen. The REAL-2 clinical trial programme started in 2000 with phase I/II trials, substituting cisplatin for oxaliplatin, since the latter is associated with greater toxicity and requires adequate hydration in patients with renal damage, and substituting 5-FU for capecitabine, eliminating the need for central-venous access and portable infusion pumps.51,52 In the phase III trial, patients (n=1,002) were randomised to one of four regimens: ECF, ECX, EOF or EOX.34 Capecitabine and oxaliplatin were found to be as effective 5-FU and cisplatin, with no significant differences in efficacy, but compared head to head, EOX was more effective than ECF. It was concluded that EOX is a convenient, effective and well-tolerated regimen. Oxaliplatin can safely be administered as a 30 minutes infusion (standard 120 minutes) in combination with capecitabine and epirubicin.53

Doublet Regimen with S-1 plus Cisplatin as an Alternative Option in Advanced Gastric Cancer

Dr Pfeiffer addressed the FLAGS study and the difference in 5-FU response between Western and Asian patients with GC. In daily practice, the dose of S-1 in Japan is 40 mg/m2 twice daily with cisplatin. The dose in the West is 25 mg/m2 twice daily with cisplatin. Recent analysis of the FLAGS data showed significant benefits in terms of QoL for CS compared with CF: patients in the CS arm showed a significantly longer time to worsening in the physical well-being subscale.54 In conclusion, CS is as effective as CF, is better tolerated, offers a more convenient schedule and therefore offers another standard therapy in aGC.

Dr Pfeiffer summarised the current knowledge on aGC as follows: oxaliplatin can replace cisplatin; capecitabine and S1 can replace IV 5-FU; and three drugs (primarily docetaxel) are more effective than two but also more toxic. He has developed a new outpatient regimen in Denmark in 2007: DOX. Phase I studies demonstrated promising efficacy,55 and phase II studies have recently completed.

Use of S-1 – Experience in Denmark

S-1 was launched in Scandinavia in March 2012, and the Danish experience of its use has been positive. S-1 has been found to be effective in daily clinical practice with a low level of HFS and less GI toxicity than other regimens. In Denmark, approved drugs (like S-1) may be used in non-approved combinations (with oxaliplatin) or indications. Dr Pfeiffer began using S-1 in GI cancer patients with HFS or GI toxicity in summer 2012 as a substitute for capecitabine, but soon started using S-1 as initialtherapy, and has used it in PC and CRC. As a result of its promising clinical trial data, together with its favourable safety profile, it is becoming a new standard therapy. A phase I study of S-1 in combination with oxaliplatin and docetaxel (DOS) has recently started. A randomised phase II study in mGC randomised patients (n=240) to DO, DOF and DOX.56 The DOF regimen was associated with improved TTP (7.7 months versus 4.5 and 5.6 months for DO and DX, respectively), RR (47 % versus 23 % and 26 % for DO and DX, respectively) and OS (14.5 months versus 9.0 and 11.5 months for DO and DX, respectively), with a better safety profile compared with TE and TEX.

In summary, a decade of separate evolution in Western countries and Japan has resulted in DOS becoming increasingly recognised as a new therapeutic option in advanced GC, both in the East and the West.

Conclusion

Drs Van Cutsem and Tabernero concluded the symposium by highlighting the promising Japanese clinical trial results and speculating whether these will translate into clinically meaningful benefits for Western patients. There is a need for a well-designed clinical trial in Western patients, as well as studies to optimise the schedule of S-1 in Western patients. In conclusion, since GC is heterogeneous in nature and origin, identifying one standard regimen for all forms is not realistic. However, a small number of active agents specifically active against GC have recently been identified. S-1 has become central to GC treatment regimens, and shows outstanding efficacy in the treatment of resectable PC, as well as efficacy in mCRC. Based on current phase III trials, it has become clear that the standard chemotherapeutic approach to mGC in Japan is essentially the same as that in other countries. Further global collaboration in the conduct of clinical trials is necessary to facilitate the timely evaluation of these agents in other GI cancers.