Thyroid cancer accounts for approximately only 1% of all reported malignancies, but is the most common endocrine malignancy.1 It is of either follicular cell origin with well-differentiated papillary thyroid cancer and follicular thyroid cancer, poorly differentiated thyroid cancer (PDTC), and anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC), or of parafollicular C-cell origin with medullary thyroid cancer (MTC).2 ATC, one of the most aggressive malignancies in humans, accounts for approximately 2–5% and MTC for approximately 3–5% of all thyroid cancers.2 Owing to their distinct clinical and molecular characteristics, different multimodal treatment strategies have to be pursued.

While ATC is characterized by an almost fatal outcome, with survival that rarely exceeds one year regardless of the available therapy,1 unselected patients suffering from MTC have an overall 10-year survival of approximately 70% following primary surgery.3,4 However, little effective therapy has existed until recently for patients with unresectable MTC.4 Because of the rarity of the disease, large-scale prospective studies are scarce and thus, until now, most progress has come from retrospective analysis of treatment data collected over several decades. While surgery is the only curative treatment option in MTC,4 the exact role and sequence of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy in the multimodal treatment strategy in ATC is still a matter of debate.

Recent pre-clinical studies have identified a large battery of molecular alterations in thyroid cancer that provide the basis for the development of molecular targeted therapy for patients with progressive disease.2,4–6 Several novel compounds with promising activity in pre-clinical studies are currently being evaluated in small clinical trials, with promising results overall. However, the impact of these emerging therapies on the clinical course of the disease is yet to be defined. This short article will summarize the data on multimodal treatment strategies in ATC and provide an overview of the new treatment options for MTC and ATC, with an emphasis on molecular targeted treatment.

Molecular Targets in Thyroid Cancer

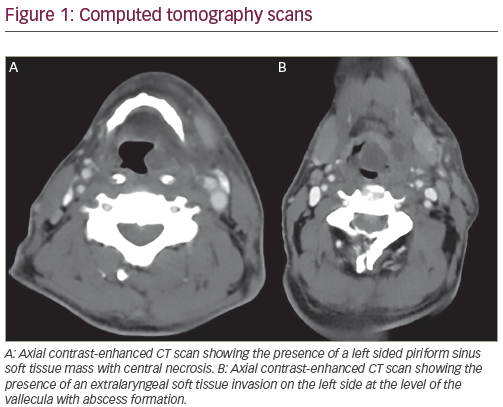

Increased knowledge of the molecular biology of thyroid cancer has led to the development of new potential treatment options for patients suffering from progressive disease. Several alterations in cell-cycle control, growth factor signal transduction, or regulation of apoptosis crucial for the development of ATC or MTC have been identified in cell line studies and analysis of clinical specimens (see Figure1).2,5

Potential Targets in Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer

The pathogenesis of ATC is still somewhat controversial. Arguments exist for a de novo development of ATC, whereas other experimental data suggest a transformation from more differentiated tumors into poorly differentiated forms, and finally to ATC through chromosomal instability and a series of sequential molecular alteration.2,7 The emergence of a more complex genotype and specific mutations in genes such as BRAF are indicative of a more aggressive phenotype.2

Prerequisite molecular features of ATC are p53 mutations in 80%, RAS mutations in 70%, BRAF mutations in 30–60%, and mutations of β-cateninin 70% of all ATC.2,8 Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclin E and D is evident in 60–80% and 70%, respectively.6,9 Expression of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and overexpression of aurora A and B are frequently found in ATC.6,10–12 Further potential targets in ATC are the p53–MDM2 interaction,6,13 Bcl-2, and angiogenesis.6 Additional information is provided in Table 1

Potential Targets in Medullary Thyroid Cancer

The development of hereditary MTC is strongly associated with the activation of the RET proto-oncogene.4 RET mutations are found in up to 98% of hereditary MTC and in up to 35–50% of sporadic MTC.4 Mutated RET provides mitogenic and survival signals. Loss of heterozygosity in the von-Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor locus occurs at the somatic level in familial MTC.14 This leads to increased expression of the hypoxia-inducible factor I (HIF-I), which promotes tumor angiogenesis by overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).4,15 In addition to angiogenesis as a promising target, mutations of pRb, PTEN, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors are of potential clinical relevance.4 As suggested by pre-clinical studies, targeting the RAS–RAF– ERK, PI3K–AKT, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)pathways holds promise.4,16 Inhibition of growth factor receptors such as IGF-I receptor and fibroblast growth factor reduced growth of tumour cells in vitro.4,17 For additional information, see Table 1. Medullary Thyroid Cancer

Prognosis and Standard Treatment

In MTC, the main independent prognostic indicators of recurrence of disease and mortality are the patient’s age and the extent of disease at the time of diagnosis.3 The pre-operative level of calcitonin predicts the probability of achieving biochemical remission and normalization of calcitonin after initial treatment correlating with a definite cure in about 95% of patients.3 However, detectable levels of calcitonin after initial treatment do not rule out long term survival.3

In asymptomatic patients harboring RET germline mutations, thyroidectomy is performed preferably before the occurrence of MTC.18 Surgical treatment with total thyroidectomy and lymph-node dissection of ipsilateral and central compartments is the cornerstone of primary treatment of hereditary or sporadic MTC.3,4 In patients without lymph-node involvement, calcitonin levels are below the detection level in 60–90% at two to three months following primary resection.4 Persistent disease has to be considered if calcitonin remains detectable. There seems to be a positive correlation between calcitonin level and tumor burden.4 In cases of the disease remaining or of relapse with tumor mass in the neck or mediastinum, re-operation is usually indicated, but the probability of biochemical cure is less than 40%.4 In patients with persistently elevated calcitonin levels, external radiation therapy may decrease the risk for recurrence.19 Distant metastases that often affect multiple organs, particularly the lung, bone, and liver, are the main cause of disease-related death.4 Once distant metastases are present, survival rates decline to 25% at five years and to 10% at 10 years.4 Relief of symptoms is the major aim of treatment of metastatic disease. Loperamide or somatostatin analogs could be effective to transiently control calcitonin-induced diarrhea.4,20 In addition, somatostatin analogs alone or in combination with interferon have some efficacy in reducing serum calcitonin levels but rarely induce tumor remissions.20 Bone metastases are treated by surgery, external radiation, or chemoembolization and application of bisphosphonates.4 Chemoembolization of clinically dominant liver metastasis may be active in reducing tumor burden and controlling tumor-associated symptoms, particularly diarrhea.21

The effect of chemotherapy on overall survival cannot be properly assessed because of an insufficient number of patients in a few prospective clinical trials. However, chemotherapy has the potential to improve symptoms and thus should be considered in the palliative treatment situation at disease progression.3,4 Transient tumor responses in up to 20% have been observed with doxorubicin or aclarubicin alone.22 Symptomatic improvement and response rates similar to doxorubicin were seen with combinations of fluorouracil (5-FU)/ dacarbacin or 5-FU/streptocotocin.3

Molecular Treatment

The only curative treatment in MTC is surgery. Novel treatment options are mandatory for patients with either persistent or recurrent unresectable disease. Promising molecular targets identified in MTC are the RET protein and the VEGF system.4 Several RET kinase inhibitors currently in clinical phase I/II trials are multikinase inhibitors and have additional inhibiting activity, most importantly against the VEGF receptor (see Table 2). Initial results from phase II trials with vandetanib, axitinib, or motesanib show some partial responses and a large proportion of prolonged disease stabilization.4,5 The data available at present indicate that not all MTC could sufficiently be treated by targeting only RET. The optimal duration of therapy is yet to be defined, and the impact of such a treatment on overall survival and prognosis is still unclear.

Currently, several pre-clinical and phase I/II trials have been launched to investigate the combination of multikinase inhibitors and conventional chemotherapy in various tumors, providing useful data on activity and toxicity for the design of phase II studies for combinations of targeted agents and conventional chemotherapy in MTC. Future experimental work has to delineate potential alterations in the downstream signaling pathways of RET and identify further crucial molecular lesions as potential targets in RET-negative MTC.

Heat shock protein 90 is a chaperone that acts to stabilize growth factor receptors and cell signaling molecules. Its inhibition leads to RAF-1 depletion and inhibition of MAPK activation. A current phase II study is recruiting patients with locally unresectable differentiated thoracic cancer or MTC to be treated with 17-allylaminogeldanamycin (17AAG),a heat shock protein 90 inhibitor (see Figure 1).Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer

Prognosis and Current Treatment

Although ATC accounts for only 1.6% of all thyroid cancers, it is responsible for more than half of the 1,200 deaths attributed to thyroid cancer in the US each year.23 Fortunately, the incidence of ATC has been declining over the past few years despite an increase in the incidence of well-differentiated thyroid tumors. The mean age at diagnosis is 55–65 years, and the incidence peaks in the sixth to seventh decade.23 The clinical presentation is usually a rapidly enlarging anterior neck mass, with a doubling of tumor volume sometimes within a week, dysphagia, dyspnea, and vocal cord paralysis.24 ATC is usually locally advanced at presentation, and 50% of patients show evidence of metastatic disease.24 Median survival of patients with localized disease is eight months, and three months with metastatic disease.25 The prognosis seems to be determined by age, sex, size of the primary tumor, complete resection, and extent of the disease.26,27 A prognostic index was developed by Sugitani et al.28 and is based on the most important risk factors: acute symptoms, tumor >5cm, presence of distant metastasis, and white cell count > 10,000/μl.

Most patients with ATC die within a few months after diagnosis, primarily due to strangulation by local tumour invasion. Consequently, local disease control is of major importance and might potentially extend overall survival. From retrospective data analysis there is evidence that a single treatment modality is insufficient to achieve stable local control.26,29 Long-term survival was observed only in patients who were treated with a combined approach using surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.1,25,26,30 However, to date, the optimal sequence of local treatment modalities has not been defined. Surgery usually consists of a total thyroidectomy. Radiotherapy in more recent series was applied as hyperfractionated radiotherapy, and chemotherapy was applied parallel to radiation as a radiosensitizer with doxorubicin or mitoxantrone.1 Some studies continued chemotherapy after completion of local treatment.31 By increasing the local control rate, distant metastases gain more relevance for overall survival.

The most commonly used chemotherapeutic drug in ATC is doxorubicin either as monotherapy or in combination with cisplatin.32–34 However, although some responses have been seen, an effect of treatment on overall survival has not yet been proved.35,36 New chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel, either alone or in combination, may increase response rates and survival. In a phase II study reported by Ain et al.,37 paclitaxel monotherapy induced a promising 53% response rate. Whether this high activity translates into increased survival remains unclear. More active drugs or drug combinations are mandatory to achieve a significant improvement of the still dismal clinical outcome.

Multimodality Treatment

The main causes of death in untreated ATC are local complications such as strangulation due to rapid tumour progression.30,38 Multimodality treatment, including surgery, radiation, or radiochemotherapy and chemotherapy, can increase the local tumor control rate.26,30,31,39–41 However, the optimal sequence of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy is still a matter of debate.1 It is generally agreed that a complete resection of the local tumor either before or subsequent to radiochemotherapy may improve the overall prognosis.35,41,42

In earlier series, surgery is commonly used as first-line treatment in resectable cases, followed by either radiation or radio- chemotherapy.24,26,31,34,41–43 More recent studies have evaluated preoperative radiation or radiochemotherapy and increased the applied radiation dose from <30Gy to hyperfractionated dose schedules with total doses between 45 and 60Gy.1,39,40,44 Independent of the sequence used for combined treatment, long-term survival occurred only in the group of patients treated aggressively with radiation, chemotherapy and surgery, achieving a complete local tumour resection.1,26,31,35,39,40,45 Considering the fact that a complete tumour resection improves overall survival, pre-operative radiation or radiochemotherapy might be advantageous, since it may enhance operability.39,40,45 Also in favor of pre-operative radiation or radiochemotherapy is the notion of Tennvall et al.39 that a surgical biopsy or attempted resection might delay the initiation of further local therapy due to poor wound healing.

A randomized, prospective, multicenter clinical trial is necessary to finally clarify the question of the optimal sequence of multimodality treatment. Molecular Targeted Therapy

New insights into molecular treatment options for ATC were mainly derived from pre-clinical in vitro or in vivo studies. PPAR-γ is a member of a superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors. High expression of PPAR-γ has recently been described in ATC cell lines.46 Treatment with PPAR-γ ligands led to the induction of apoptosis and downregulated the invasive potential of these cell lines.46 Additional data suggested that PPAR-γ ligands may enhance etoposide-induced apoptosis.47 Based on these data, a phase I/II clinical study has been launched to evaluate the activity of a combination of paclitaxel and the oral PPAR-γ agonist CS7017. Several multikinase inhibitors have been evaluated in clinical phase I/II studies in solid tumors. Some of them include patients with ATC. Axitinib, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with particular activity against VEGF receptor,1–3 PDGF-R beta and KIT, induced a partial response in a patient with ATC.48

Further studies currently recruiting investigate the activity of vascular and growth factor targeting agents such as sorafenib, pazopanib, or sunitinib in PDTC and ATC (for further information see clinicaltrials.gov and Table 2 and Figure 1). Combretastatin A, an anti-endothelial agent that exerted some activity in ATC as a single agent,5 is currently being studied in ATC in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin. Several further molecular targeted therapies are currently being studied in pre-clinical models. The most promising or advanced approaches are summarized in Table 1.

Concluding Remarks

Despite significant progress in decoding the molecular biology of thyroid cancer, the outcome of ATC is still dismal. Aggressive multimodal locoregional treatment reduces the rate of local relapse. However, due to the lack of active systemic treatment regimens, patients die of metastatic disease. New molecular targeted agents are currently in early clinical evaluation, with partly promising results.

In MTC, no effective therapy existed for patients with unresectable disease until recently. The identification of the RET proto oncogene as the main driving force of MTC led to the introduction of targeted agents in the treatment concept of MTC. Activity was proven in several phase I/II clinical trials. The emerging therapies in thyroid cancer raise new hopes, but their impact on clinical outcome needs to be further elucidated by well-designed randomized clinical trials. ■