“It is difficult to evaluate what did not happen.” – Academician, LV Gromashevsky

The COVID-19 pandemic may be considered the first global health catastrophe in the past 100 years, since it has affected not only economic, political and medical paradigms, but also our way of life.

The rate and distribution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, despite the implemented global sanitary and anti-epidemic measures, demonstrated numerous disparities in quarantine strategies, as well as a mismatch of social behaviour and attitudes to the level of danger. However, in many countries there have been no voluntary lifestyle changes in order to maintain adequate long-term safety during the pandemic. Furthermore, social distancing measures, mask wearing, and prohibition of public or private activities, have been widely perceived as an encroachment on constitutional freedoms and rights.

These disparities, as well as lack of effective vaccines, unified treatment protocols, reliable diagnostic criteria, stable sensitive test systems, track and trace procedures, and monitoring of people isolating or recovering after COVID- 19, have resulted in a high probability of worse disruption in the expected second and subsequent waves of the COVID-19 outbreak. Small town and district communities face substantial challenges if their only multidisciplinary hospitals are not ready to accept patients with COVID-19. Furthermore, patients with acute surgical or cerebrovascular disease may receive suboptimal care if all available resources are directed to the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COVID-19. If everyone with suspected symptoms of COVID-19 presented at the hospital, sanitary standards would be violated. Protection of medical staff from infection is difficult when, from the announcement of the pandemic, personal protective equipment was critically lacking and safe-working practices were not established. Moreover, many people considered the threat to be exaggerated, making it difficult to deploy comprehensive COVID-19 countermeasures. Some medical workers proposed ideas to minimise infection risk, but later violated them, especially regarding change of clothes, disposal of infected medical waste, use of insulating suits and other personal protective equipment when providing medical care to patients with COVID-19. While some physicians were willing and able to work responsibly, others quit their jobs.

The reform of the healthcare industry in Ukraine has been impaired by significant shortcomings and contradictions. The old ‘post-Soviet’ medical architecture and the patient’s place have been replaced by models with vague concepts of ‘medical service’ and market-driven concepts of medical care, which are not patient-centred. Patients have not yet developed a culture of co-operation with family doctors. In addition, a change in the financing model and decentralisation of medical management caused an administrative and managerial collapse and a shortage of specialists. The crack between the public and private sectors of medicine eventually turned into a tectonic fault. Consequently, the city community faced seemingly insurmountable challenges, and the desire to address the COVID-19 epidemic at the local level was disappointing. By mid-March 2020 the city and the district still did not have an effective action plan, sufficient budget or necessary resources. The hospital reported a deficit of mechanical ventilation devices, monitors, medicines, and basic medical devices. Panic among the population grew.

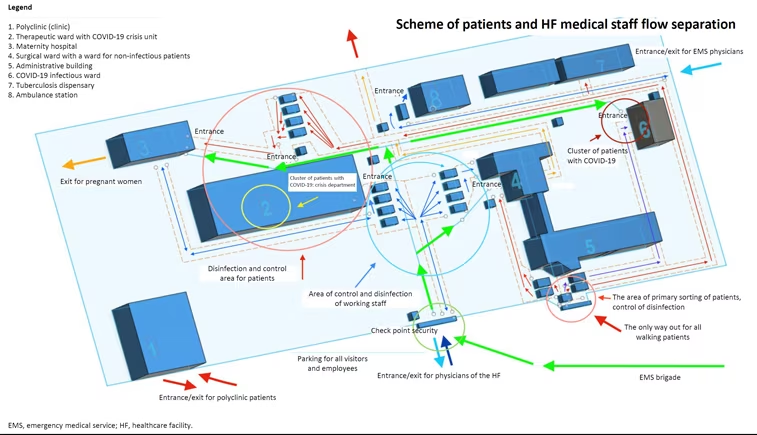

The city authorities turned to the private medical sector for help, because some highly-specialised private clinics had implemented successful systems for infection control. Our strategy was to deploy a sanitary sorting and demarcation medical tent camp on hospital grounds (Figures 1 and 2) with decontamination and disinfection zones for specialised vehicles – ambulance, patients, hospital visitors, as well as for medical staff. This allowed separation of patient flow from that of the movement of medical staff, and sorting of patients with signs of respiratory diseases according to risks and severity. It also facilitated protection of hospitalised patients who were unable to be discharged ahead of schedule. It minimised contact among patients at high risk of infection and at high risk of severe complications, and also ensured the protection of patients with special needs, pregnant women, patients with cancer, patients with mental disorders, and potentially infected medical staff on the territory of Brovary Hospital. We set up four quarantine corridors:

– Red (infectious): for patients with suspected COVID-19 and for patients with COVID-19 who were referred by family doctors;

– Yellow: for patients with non-infectious diseases, for who had not been diagnosed with COVID-19, but were still considered potentially dangerous;

– Green: for medical staff;

– Blue: for employees of the infectious diseases ward and emergency medical care station who were at particular risk of infection due to inadequate protection.

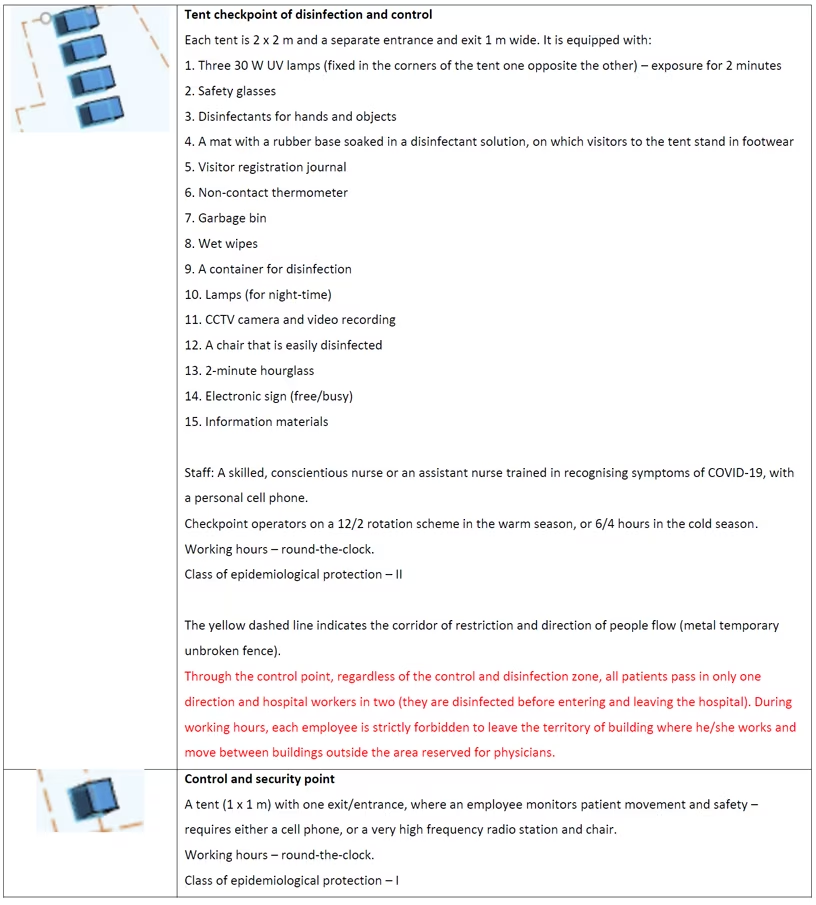

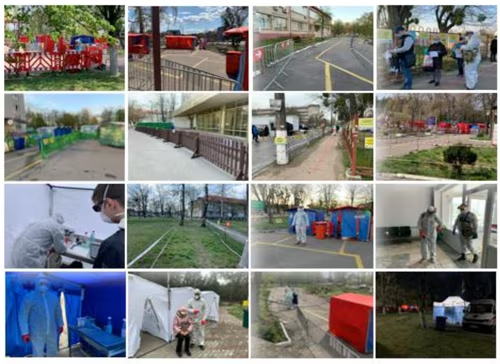

Each corridor had its own checkpoint, where everyone underwent non-contact thermometry, disinfection of hands and shoes, and ultraviolet treatment of outerwear and some personal items. The red and yellow quarantine corridors were additionally equipped with a sorting platform where doctors filled in questionnaires and collected epidemiological data, from which patients were referred to either primary care or to hospital medical specialties. All quarantine corridors were fenced and ended at a specialised hospital building. Compliance to the rules was enforced by autonomous law enforcement posts and a video surveillance system. Information was monitored in real time, allowing any violations to be quickly resolved. The throughput delay in the control and disinfection zone was 3–4 minutes/person. Therefore, the capacity of 23 tent checkpoints was about 250 people/hour. Queues developed at the hospital entrance, but these were regulated by waiting areas and social distance markers. The average queuing delay was up to 15 minutes.

The entire medical tent camp, including the checkpoint and quarantine corridors, was equipped with infographics and accessible navigation, indicating the direction of movement. In addition, information was duplicated on diagrams and information boards. For people with special needs, including pregnant women, patients with cancer, patients with diabetes mellitus, or those who needed haemodialysis, simplified routes were created to ensure minimal delays. All entrances/exits, except those that continued into the quarantine corridor, were blocked. Strict restrictions were also applied to traffic. Only ambulances, company cars and cars transporting patients to the emergency department were allowed. After unloading a patient, vehicles went to a disinfection zone, where personal protective equipment was disposed of, and the vehicle disinfected externally and internally.

In preparation for an increased demand for beds, we planned to deploy a crisis centre in the therapeutic building, initially with 25 beds. In the maternity ward, all birthing partners and visits were prohibited. For an infected woman in labour, a separate area in the crisis centre was created, where a specially instructed delivery team were equipped and maximally protected.

Since visiting was forbidden, one family representative was permitted to enquire about the patient’s condition by electronic request or by phone. Standardisation of this service minimised the number of calls received. Accommodation was provided for contact physicians, where they could temporarily live between their frequent duties. All used clothing and personal protective equipment were stored in a separate security zone after disinfection, facilitating control over their disposal. The entire medical camp was completely disinfected and wet cleaned twice a day. Additionally, the red quarantine corridor was disinfected after each infected patient had passed through.

The medical camp team involved 40–46 volunteers, most of which did not have a medical education, and therefore were involved only in questionnaire, decontamination and disinfection procedures. Medical camp staff worked in 23 tent checkpoints on a rotational basis. Although the checkpoint tents were well ventilated, all members of the medical camp staff were dressed in an insulating bioprotective suit, FPP2 respirator, glasses, a protective shield, two pairs of latex gloves and ‘street’ shoe covers. Only hospital workers (about 1,200 people daily) went through the green and blue quarantine corridor.

During April 2020, 26,604 patients applied for medical help, which decreased to 14,115 people during May. After assessment, only 13,251 patients were admitted to secondary care in April, the rest (13,357) were referred to primary care. This proportion changed substantially in May, when 12,745 were admitted and only 1,370 referred to their family doctor. This may be explained either by a gradual reduction in the mood of panic, or news spreading that patients with subfebrile temperature and cough were not allowed in the hospital. The number of patients admitted to secondary care decreased slightly, the only difference being, a reduction in the number of patients who were sent to the red quarantine ‘infectious’ corridor from 334 in April to 262 in May (-22%).

The number of disinfected ambulances passing our checkpoints directly to the emergency department or the infectious diseases department, and then to the disinfection zone increased from 958 in April to 1,145 in May (+16%). This can be explained by the fact that the percentage of patients with infectious complaints among passengers of ambulances was 15.77% higher in April than in May. During the 2 months, 596 patients (3% of all patients) with suspected COVID-19 and other viral diseases passed the infection corridor: 334 in April and 262 in May. A total of 11,476 patients (44%) attended the policlinic, 7,353 (28%) the surgical department, 4,269 (16%) therapeutic department, and 2,329 (9%) went to the hospital.

We achieved complete decontamination and disinfection of 4,616 vehicles: 2,938 ambulances, 795 official carriages, and 881 private cars. Infection control measures (sanitary and anti-epidemic measures, sanitary treatment of hands, shoes, clothes, thermometry, surveys and questionnaires) were performed on 73,811 people. In addition, 954 violations of sanitary and epidemiological measures by hospital staff were identified and eliminated. During the period of the medical camp operation, none of the employees of the camp became ill, double diagnostic tests did not reveal COVID-19 infection among workers. Among 1,200 employees of hospital medical staff, only six became infected, and infection was reported as early as March 2020, when the medical camp was not fully operational.

In summary, in unison with the requirements of the National Quarantine in the short term (about 14 days) with a minimum and affordable budget, on the territory of the medical camp and hospital, as an integrated facility with a high concentration of potentially infected people, we implemented and ensured strict control of the main sanitary anti-epidemic measures that responded to all the above-described challenges and needs of the epidemiological situation in the region.

Figure 1: The scheme of the organisation of the medical tent camp

Figure 2: Examples of quarantine corridors and disinfection zones

Author profile

Olexandr Kulyk, MD, is a neurosurgeon, a physician of neurofunctional diagnosis and neurological rehabilitation, the merited doctor of Ukraine, MD (doctor of medical sciences) and the director of the Neurological and Neurosurgical Rehabilitation Research Centre (NODUS) in Brovary, Ukraine. He received his medical degree from the University of Medicine, Chernivtsi, Ukraine, and received subsequent degrees in neurosurgery, functional diagnosis and healthcare management. He worked as a neurosurgeon in the Children’s Regional Hospital, Zhytomyr, in the Regional City Centre of Emergency and Disaster Medicine, Kyiv, in the City Children’s Neurosurgery Centre, Kyiv, Ukraine. His areas of research interest include neuro trauma and injures, cerebrovascular diseases, neuro-oncology (children and adults), neurological rehabilitation and functional diagnosis. He is a prominent scientist in Ukraine, who has published many articles, and given many presentations at scientific congresses and conferences, and is a member of the World Federation for NeuroRehabilitation.

Disclosure: Olexandr Kulyk has no financial or non-financial relationships or activities to declare in relation to this article.

Support: Edited and supported by Touch Medical Media. No funding was received in the publication of this insight article.

Published: 31 July 2020