Today, lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the world. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of lung cancer, and 40% of these patients present at an advanced stage, including patients with metastatic disease and those with locally advanced disease with malignant pleural or pericardial effusion.1 Platinum-based chemotherapy with third-generation agents (gemcitabine, vinorelbine, docetaxel or paclitaxel) improves survival and quality of life compared with best supportive care alone. Despite these advances in treatment, a therapeutic plateau has been reached using conventional chemotherapy. Over the past decade, large randomised studies have demonstrated the relative equivalence of platinum-based doublets, with response rates of 16–32% and median survival ranging from eight to 11 months, with one- and two-year survival rates of 35–45% and 10–20%, respectively. The majority of patients experience disease progression, generally after a median of three to six months of initiating chemotherapy, and the long-term prognosis is still poor.2 Therefore, there is a great unmet need to provide more effective therapeutic strategies to further improve outcome in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Further understanding of cancer biology has allowed the development of several potential molecular targets for cancer treatment. Numerous targeted agents have been evaluated in clinical trials of cancer treatment, and a number of phase III trials have generated definite results. In particular, several agents that target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the angiogenesis pathway have proved efficacious in the management of NSCLC. To further improve the outcome of first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC, there is much interest in adding these targeted agents to platinumbased chemotherapy. This article will focus on the potential beneficial role of these targeted agents in the management of advanced NSCLC in the first-line treatment setting.

Bevacizumab

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a potent proangiogenic factor expressed by most cancer cell types and certain tumour stromal cells. As cancer progression and metastasis are dependent on angiogenesis, VEGFtargeted therapies have become an important modality of cancer treatment.3 Bevacizumab, a recombinant humanised monoclonal antibody against VEGF, has demonstrated a clinical benefit when administrated in combination with chemotherapy in chemo-naïve advanced NSCLC patients with nonsquamous histology and no brain metastases.4,5 In a large randomised trial (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 4599), the addition of bevacizumab to paclitaxel and carboplatin significantly improved overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and response rate (see Table 1).4 However, toxicity was increased in the bevacizumab arm, including higher incidences of febrile neutropenia, haemoptysis and haemorrhage. A recent subset analysis of ECOG 4599 has shown that bevacizumab treatment in elderly patients (aged 70 years) was associated with a higher incidence of severe toxicity, but no obvious improvement in OS.6 Although these findings are limited by the retrospective post hoc nature of analysis, elderly-specific prospective studies are needed to establish the safety of combinations of novel agents for the treatment of advanced NSCLC.

A European randomised phase III trial, Avastin® in Lung (AVAiL) BO17704, also confirms the role of bevacizumab in this selected patient population.5 Both bevacizumab doses (7.5 and 15mg/kg) in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin significantly improved PFS versus placebo (see Table 1). A recent update also confirmed the clinically and statistically significant improvement in the primary end-point of PFS for the two different doses of bevacizumab studied in the trial compared with chemotherapy alone. However, this study did not demonstrate a statistically significant prolongation of OS, a secondary end-point, for either dose in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone.7 In this study, the exclusion criteria were as outlined above for the ECOG 4599, with additional exclusion criteria of radiological evidence of tumours invading or abutting major vessels as a further safety precaution. Thus, no significant difference in pulmonary haemorrhage was observed among treatment arms.

On the basis of these data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) approved bevacizumab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy for first-line treatment in a selected patient population. While trials assessing the safety and feasibility of bevacizumab in patients with squamous histology and brain metastasis are ongoing, bevacizumab treatment with chemotherapy is currently suitable for patients with non-squamous histology, minimal baseline haemoptysis and no central nervous system (CNS) metastasis.

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors

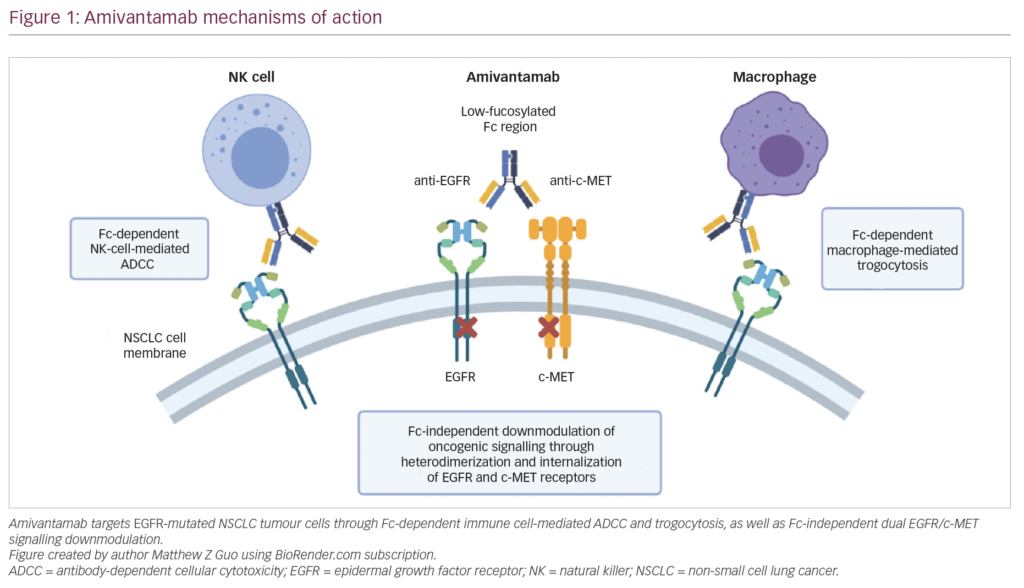

The EGFR is a tyrosine kinase (TK) receptor that is overexpressed in 50–90%of NSCLC,8 and its activation promotes cancer-cell proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis. Monoclonal antibodies directed against EGFR, i.e. cetuximab, target the extracellular domain of EGFR to prevent ligand binding and receptor activation. Small-molecule TK inhibitors (TKIs) such as erlotinib and gefitinib bind the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding pocket of the receptor to prevent ligand-induced phosphorylation and downstream signalling.9

Erlotinib and Gefitinib

Both gefitinib and erlotinib, the first-generation EGFR-TKIs, have single-agent activity in NSCLC and are currently used for treatment of advanced NSCLC. On the basis of pre-clinical data demonstrating that EGFR TKIs enhance the efficacy of cytotoxic agents against a range of human tumour xenografts, including lung cancer, four randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trials examined the combination of erlotinib or gefitinib with platinum-based chemotherapy as the first-line therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC (see Table 2).10–13 Although the addition of erlotinib to carboplatin and paclitaxel (CP) significantly prolonged survival in the subgroup of patients who had never smoked,12 most clinical trials did not demonstrate any survival advantage with the addition of erlotinib or gefitinib to chemotherapy.10,11,13 One possible explanation for the negative results may be the lack of patient selection for known prognostic factors in these trials. Since only one subgroup of patients with NSCLC has tumours that are dependent on the EGFR pathway, such as never having been a smoker and EGFR mutations, few patients would have a clinical benefit from EGFR-TKIs, thus overall trials could be underpowered to detect an effective therapy.9 In addition, these trials used the continuous administration schedule of gefitinib or erlotinib from the beginning of chemotherapy. Recently, there has been growing pre-clinical evidence of a possible sequence-dependent antagonism between EGFR-TKIs and cytotoxic agents as a result of G1 arrest of tumour cells by EGFR-TKIs, which protect tumour cells from cell-cycle-specific cytotoxic agents. Therefore, the combination of EGFR-TKIs with chemotherapy could be synergic if exposure of EGFR-TKIs before chemotherapy is avoided.14 These results have led to clinical trials of sequential administration of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs. Recently, a phase II randomised doubleblind trial of sequential erlotinib and chemotherapy as the first-line treatment (FAST-ACT) in patients with advanced NSCLC found that sequential administration of erlotinib with gemcitabine plus either cisplatin or carboplatin chemotherapy significantly prolonged PFS compared with the placebo arm, which met the primary end-point of this study at 7.2 versus 5.5 months, respectively; p=0.005 (see Table 2).15 As well as the sequence-dependent synergic antitumour activity, several in vitro studies have suggested that gefitinib or erlotinib significantly reduced thymidylate synthase (TS) expression through inhibition of transcriptional factor E2F- 1.16,17 As pemetrexed is a potent inhibitor of TS, resistance to pemetrexed may be mainly related with increased expression of TS in tumour cells. Therefore, sequential drug exposure can modulate interaction between EGFR-TKIs and pemetrexed. Based on these findings, a randomised phase II study is under way to compare the PFS of an intermittent combination of erlotinib plus pemetrexed with that of pemetrexed alone in patients with recurrent NSCLC.

Cetuximab

The chimaeric anti-EGFR immunoglobulin (Ig)-G1 monoclonal antibody cetuximab has been approved for the treatment of EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal carcinoma in patients who are refractory to irinotecan-based chemotherapy for use in combination with radiation therapy for the treatment of locally or regionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), and as a single agent for the treatment of patients with recurrent or metastatic SCCHN for whom prior platinum-based therapy has failed. It has a five-fold greater affinity for the EGFR than the natural ligands, and inhibits ligand-induced activation of EGFR. Unlike EGFR-TKIs, cetuximab stimulates EGFR internalisation, effectively removing the receptor from the cell surface for interaction with the ligands. It has also been shown to elicit antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in certain tumour types in vitro.9

In pre-clinical studies, cetuximab alone inhibits the in vitro growth of some, but not all, EGFR-expressing NSCLC cell lines. Increased antitumour activity effects have been observed in vitro when cetuximab was combined with chemotherapy. Enhanced efficacy has been observed in patients with colorectal cancer and head and neck cancer when treated with cetuximab plus chemotherapy compared with cetuximab alone.18 While cetuximab is marginally active as a single agent in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced NSCLC, most phase II studies suggest that adding cetuximab to platinumbased chemotherapy is of benefit. A randomised phase II study evaluated the efficacy of cetuximab with gemcitabine/platinum chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in chemo-naïve patients with advanced NSCLC.19 Cetuximab has also been studied in combination with cisplatin/vinorelbine chemotherapy as the first-line treatment in patients with EGFR-detectable NSCLC.20 Patients in the cetuximab combination arm showed a higher response rate and longer PFS and OS than those treated with chemotherapy alone, which suggests that adding cetuximab may improve the efficacy of platinumbased doublets in the first-line treatment of NSCLC (see Table 3).

Recently, a large randomised phase III trial, First-line in Lung cancer with Erbitux (FLEX), in 1,125 patients with EGFR-detectable advanced NSCLC demonstrated that OS was significantly improved for those who received cetuximab plus cisplatin plus vinorelbine (CV) chemotherapy compared with those who received CV alone (11.3 versus 10.1 months, respectively, hazard ratio [HR] 0.871, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.762–0.996; p=0.0441); see Table 3.21 The benefit of the cetuximab and CV combination was seen in patients with all histological subtypes of NSCLC. In addition, subgroup analyses suggested a greater benefit in Caucasians independent of histology (10.5 months versus 9.1 months, respectively, HR 0.8, 95% CI 0.692–0.924; p=0.0025); see Table 3. The main side effect of cetuximab was acne-like skin rashes, which were manageable with medication. Another phase III trial, performed in the US, evaluated the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with carboplatin/taxanes versus carboplatin/taxanes alone in the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC (BMS 99).22 The addition of cetuximab resulted in a trend towards a longer PFS in analysis performed by the independent radiological review committee, which reached statistical significance in the analysis carried out by the investigators of the trial. OS data are pending.

Multitargeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Sorafenib

Sorafenib is a small molecule with activity against several TKs, including Raf-1, VEGF receptor (VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR).23 A randomised discontinuation, placebo-controlled phase II study was conducted with sorafenib (400mg orally twice daily) in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced NSCLC (E2501).24 Preliminary results have been reported for 342 patients. After an eight-week induction phase, 107 patients with disease stabilisation were randomised to remain on sorafenib (n=51) or to take placebo (n=32). The median PFS after randomisation was longer with sorafenib than with placebo (3.6 versus two months, respectively; p=0.009). Major toxicities were manageable. The authors concluded that sorafenib demonstrated single-agent activity and clinical benefit in previously treated NSCLC patients. Meanwhile, a phase III trial evaluating sorafenib in patients with NSCLC was stopped early following a planned interim analysis. The phase III Evaluation of Sorafenib, Carboplatin and Paclitaxel Efficacy in NSCLC (ESCAPE) trial evaluated sorafenib in combination with CP in chemonaïve patients with advanced NSCLC.25 This multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled 926 patients. Safety events were generally more consistent than those previously reported. However, sorafenib-treated patients with squamous cell carcinoma had a greater mortality rate than those with non-squamous histology. Preliminary results showed a median survival of 10.7 months in the sorafenib arm versus 10.6 months in the placebo arm. The independent data monitoring committee concluded that the study would not meet its primary end-point of improved survival, and recommended termination of the study. An ongoing randomised phase III trial combining sorafenib with gemcitabine and cisplatin, Nexavar plus gemcitabine and cisplatin (NEXUS), which was originally investigating PFS in patients with all histology types, has now been amended to exclude patients with squamous histology.24

Vandetanib (ZD6474)

Vandetanib (ZD6474) is an inhibitor of VEGFR-2 and EGFR TK activity. It was also evaluated as the first-line treatment in 181 patients who were randomised to vandetanib alone, vandetanib plus CP, or placebo plus CP. No significant difference was found in PFS or OS between the chemotherapy alone and the chemotherapy–vandetanib arms. The vandetanib alone arm was terminated prematurely because of a low PFS. Vandetanib is currently the subject of phase III trials in advanced NSCLC.25

Cediranib (AZD2171)

Cediranib (AZD2171) is a highly potent and selective VEGF signalling inhibitor that targets VEGFR-1, -2, and -3. Encouraging antitumour activity was observed in a phase I trial of first-line cediranib plus CP in a patient with advanced NSCLC. A phase II/II trial (BR24) comparing CP with or without cediranib as the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC was under way, but will not continue into phase III due to an imbalance in toxicity following the planned end of phase II efficacy and tolerability analysis by the study’s Data Safety Monitoring Committee.25

Sunitinib

Sunitinib is a multitargeted receptor TKI against VEGFR and PDGFR as well as several others. Initial phase II trials demonstrated single-agent activity of sunitinib in previously treated patients with advanced NSCLC. It is currently being evaluated in combination with a number of standard regimens commonly used in NSCLC, and also as maintenance monotherapy after first-line platinum-based treatment of advanced NSCLC.25

Conclusions

With the emergence of the novel targeted agents, incremental progress is being made in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. The addition of bevacizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy improved survival in a selected patient population of advanced NSCLC. Recently, cetuximab in combination with cisplatin/vinorelbine chemotherapy improved OS in both squamous and non-squamous histology of NSCLC. Ongoing trials will address whether EGFR-TKIs and other antiangiogenic agents will be valuable in the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC. The identification of predictive markers would help discover how best to use these agents and in which setting they offer the most benefit for the treatment of advanced NSCLC.