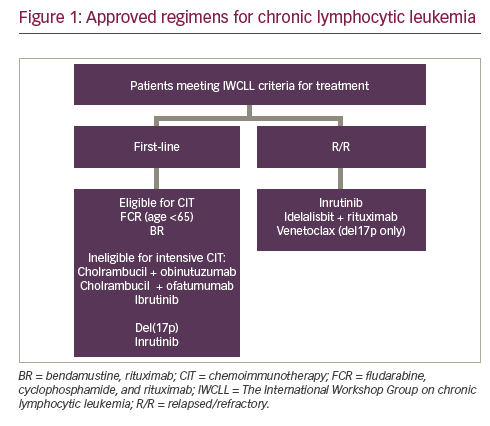

Chronic lymphoproliferative disorders (CLPD) comprise several disorders that arise from a monoclonal proliferation of mature B or T cells. Among these entities, there are many that frequently involve the blood and are usually detected in routine blood analyses, the most frequent being chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Before the advent of immunophenotyping, most CPLD were diagnosed as CLL, but advances in the morphological evaluation of peripheral blood and lymphoid tissues, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and molecular genetics have facilitated their differential diagnosis. Moreover, these new techniques are allowing to identify distinct clinico-biologic forms of CLL.1–3

Epidemiology

CLL is the most prevalent form of leukaemia. In the US it is estimated that approximately 16,000 cases/year are diagnosed with CLL. The ageadjusted incidence rate is 4.2 cases per 100,000 per year, with a clear difference between men (5.8 cases/year) and women (3.0 cases/year).4 In Europe, the incidence rate is similar (4.9 cases/year), with a similar sex distribution (5.9 for males and 4.0 for females).5 The incidence of CLL dramatically increases with age, reaching >20 cases/year in individuals older than 70, and even >30 cases/year in patients aged 80 or older. On the contrary, CLL is infrequent in persons under the age of 40 (0.2 cases/year).4 One of the most notorious epidemiological characteristics of CLL is its racial diversity. Within the US, the incidence rate is highest in Caucasian males (6.2 cases/year) and females (3.2 cases/year) compared with African Americans (4.3 and 2.0 cases/year for males and females, respectively), while Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders had the lowest incidence (1.3 and 0.7 cases/year for males and females, respectively).4 Incidence rates are even lower in the Far East, and countries such as Japan have an age-adjusted incidence of 0.48 cases/year, which is even lower than that of mantle-cell lymphoma (MCL) in that region.6 Furthermore, the clinical outcome of patients with CLL is also different across various ethnic groups. In the US, African American patients with CLL present at a younger age and with more frequent advanced disease, extranodal involvement and B symptoms compared with Caucasian patients. Consequently, African American patients had a significantly shorter event-free and overall survival, an effect that was found to be independent from other prognostic factors in a multivariable analysis.7 By contrast, in a recent series or Japanese patients, most cases had favourable prognostic markers and an excellent clinical outcome.8 It is important to note, however, that rather than diversity in the characteristics of the disease, these differences could reflect disparities in access to medical care.7

Diagnosis

The hallmark of the disease is an increased white blood cell count with a high percentage of small, mature-looking lymphocytes. In patients diagnosed on routine analysis, anaemia is found in less than 10 % of the patients. Importantly, anaemia is not always due to the infiltration of the bone marrow by the disease; other causes such as autoimmunity, iron, folic acid or vitamin B12 deficiency may account for the presence of anaemia and should be discarded when these comorbidities are under consideration.9,10 Likewise, a marked thrombocytopenia (e.g. <20,000/ ìl) should raise the possibility of an immune origin, particularly in the absence of anaemia. Hypogammaglobulinaemia is frequent (30 % of patients) and tends to worsen over the course of the disease.11 Serum immunofixation can demonstrate an M component (usually of the immunoglobulin M [IgM] type) in around 10–15 % of patients. A positive direct antiglobulin test is observed in around 5 % of the patients at the time of diagnosis, with clinically apparent autoimmune haemolytic anaemia being less frequent.12 The lymph nodes show involvement by small lymphocytes and, as a distinctive feature, proliferation centres called ‘pseudofollicles’. The bone marrow systematically displays a variable degree of infiltration by the disease and, in contrast to follicular lymphoma (FL), there is no paratrabecular infiltration.13

According to the guidelines from the International Workshop on CLL,14 the diagnosis of CLL is based on the presence in blood of more than 5,000 monoclonal B cells/ìl with a distinctive immunophenotype that persists for more than 3 months. Morphologically, leukaemic cells are characteristically small, mature-looking lymphocytes with scanty cytoplasm and a dense nucleus with partially aggregated chromatin. CLL cells are extremely fragile and can become partially broken during the preparation of blood smears; these cells are known as ‘basket’, ‘smudge’ of ‘Gumprecht cells’ and, although unspecific, are typical of CLL.13 Apart from a careful morphological evaluation of the peripheral blood, immunophenotyping by flow cytometry is the most reliable test for the diagnosis of CLL (see Table 1). On one hand, immunophenotyping will distinguish B-cell from T-cell disorders and, on the other hand, it will establish its monoclonal nature by showing immunoglobulin light chain restriction. CLL cells co-express the CD5 antigen and B-cell surface antigens CD19, CD20 and CD23. The levels of surface immunoglobulin, CD20 and CD22 are characteristically low compared with normal B cells and CD79b or FMC7 are typically absent or weakly expressed. Since there is no single marker exclusively expressed on CLL cells, a composite immunophenotype that integrates five markers into a scoring system helps distinguish CLL form other CLPD (see Table 2).15,16

Diagnosis of Other Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia-related Disorders

Monoclonal B-cell Lymphocytosis

In the absence of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, cytopenias and clinical symptoms, the presence of fewer than 5,000 monoclonal B-lymphocytes/ìl in blood with a CLL phenotype is defined as monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL),13,14 although this cut-off value was selected arbitrarily for consistency with prior guidelines and is not based on objective clinical data. Because of this, several studies have compared large series of patients with either MBL or Rai stage 0 CLL. As a result, it appears that a higher cut-off level (i.e. 10,000–11,000/ìl) could be better for distinguishing those patients who will remain asymptomatic from those who will eventually progress to symptomatic CLL.17–19 Unfortunately, the potential trade-off of a higher cut-off value is that the rate of disease progression of patients with MBL would increase as well (see Table 2).

MBL represents a miscellaneous category ranging from patients with minute clonal B-cell populations detected through general population studies20 to patients with absolute lymphocytosis that are referred for consultation, currently defined as clinical MBL.21,22 Indeed, the prevalence of MBL is closely associated with the methods used for detection. Initial studies using basic B-cell panels revealed that the MBL prevalence was 0.6 %,23 but this figure reached 5 % in adults over 60 years when a more sensitive four-colour flow cytometry test was used.24 Moreover, the Salamanca group found CLL-type clones in more than 20 % individuals over 60 years of age by using eight-colour panels and acquired five million peripheral blood cells per individual.25

The highest reported prevalence of CLL-like MBL occurs in first-degree relatives of CLL patients. Studies in both the UK and USA showed a high prevalence of CLL-like MBL (13.5–18 %) in individuals with a family history of CLL who had normal blood counts.25,26 For instance, in the UK study, and using the same study methodology in both CLL families and the general population, a fourfold increase prevalence of MBL in families with a genetic predisposition to CLL was observed.

In general, patients with clinical MBL and Rai stage 0 CLL have similar patterns of IGHV gene mutations, CD38 and ZAP70 expression and genomic aberrations as detected by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH). More recently, next-generation sequencing identified relevant gene mutations, including NOTCH1 and SF3B1, associated with advanced stages of CLL and risk of transformation.27,28 Finally, clinical MBL and Rai stage 0 CLL seem to share the same immune system perturbation and in particular the increased risk of infections.29 Conversely, it has been reported that patients with MBL frequently have a personal history of pneumonia, meningitis and even infectious episodes among their siblings or children, suggesting that exposure to infectious agents may trigger immune events leading to MBL.30

MBL does not always progress to CLL, a phenomenon that occurs in only 1–2 % cases per year.31 Moreover, in patients with clinical MBL Kaplan-Meier curves for disease progression do not display a plateau over time and therefore life-long monitoring should be scheduled for these cases, similar to what is current practice for patients with Rai stage 0 CLL.32 Another important question is whether all CLL cases are preceded by MBL or if some CLL cases develop de novo. To address this question, Landgren et al.33 studied 77,469 healthy adults who were enrolled in a US Cancer Screening Trial. Among 45 participants who were subsequently diagnosed with CLL during the study and had a prediagnostic peripheral blood sample available, MBL was present in 44 (98 %) patients, suggesting that virtually all CLL cases are preceded by MBL.

Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

The diagnosis of small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) requires the presence of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, cytopenias or other diseaserelated features with <5,000 monoclonal B lymphocytes/ìl in blood. By definition, SLL cells display the same immunophenotype as CLL cells, and the diagnosis should be confirmed by histological evaluation of a lymph node or other tissues. The histology of lymph nodes in SLL/CLL is heterogeneous. Typical lymph nodes from patients with SLL/CLL reveal effacement of the architecture with a pseudofollicular pattern of pale areas that correspond to proliferation centres on a dark background of small lymphocytes.14 Proliferation centres contain numerous T cells, a fine network of endritic cells, and B cells with an increased expression of proliferation-associated markers and anti-apoptotic molecules compared with the non-proliferation centre component. Of note, patients whose lymph nodes have expanded pseudofollicles with a high proliferation rate (the so-called ‘accelerated CLL’) tend to have shorter survival compared with patients with non-accelerated CLL.34 Within the SLL/CLL spectrum, only around 10 % of cases present as SLL and many of them eventually evolve as to fulfil CLL criteria.

Richter’s Syndrome

Richter’s syndrome (RS) represents the development of an aggressive lymphoma, most commonly a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in a patient previously (or simultaneously) diagnosed with CLL. The diagnosis needs to be substantiated by the biopsy of a lymph node or another lymphoid tissue. Rarely, RS presents in peripheral blood or bone marrow smears in the form of large immunoblasts with reticular chromatin, prominent nucleoli and basophilic cytoplasm admixed with small CLL lymphocytes. In this context, immunophenotyping is equally important as these cells tend to have a CLL phenotype with minor deviations. RS is reported to occur in 3–5 % of patients with CLL, with a 10-year-cumulative incidence of around 10 %. RS, however, is most likely an underdiagnosed situation. Clinical and laboratory clues that should raise the possibility of RS include sudden worsening of the general status, appearance of B symptoms, enlarging lymph nodes or spleen and dramatically increasing serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Risk factors predicting for the development of RS are high CD38 expression, unmutated and stereotyped IGHV genes35 and presence of NOTCH1 mutations.36 In 80 % of cases, the transformation occurs in the CLL clone, which usually acquires TP53 and MYC abnormalities and/or clonal evolution. The prognosis of these patients is poor. In the remaining 20 % of patients, the large-cell lymphoma arises in a CLL-unrelated B-cell clone, and these patients have a similar prognosis compared with patients with de novo DLBCL.35 Finally, there are infrequent cases of transformation into Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In a review of the literature, 86 such cases were identified: the disease predominated in older men and the most common histological subtype was mixed cellularity. EBV genomic integration could be demonstrated in several cases, the response to therapy was poor and the overall survival less than 2 years.37

Differential Diagnosis

Morphology

Usually, the diagnosis of CLL is straightforward, but other CLPD in leukaemic phase, particularly MCL, lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma, and marginal zone lymphoma can mimic CLL. In CLL, a small percentage (i.e. 10–20 %) of atypical lymphocytes (e.g. prolymphocytes, lymphoplasmacytoid cells, cleaved cells or centrocytes) can be present in the blood.13 Moreover, the presence of more than 55 % prolymphocytes arbitrarily separates CLL from B-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia14 a disorder which in most cases corresponds to MCL in leukaemic phase.38

Immunophenotyping

Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood cells is necessary to make the differential diagnosis (see Table 1). In difficult cases, immunophenotyping tests performed on lymph node or bone marrow samples, as well as genetic and molecular studies, can be quite useful. Apart from the common antigens mentioned above, CD43 and CD200 may provide further information in the differential diagnosis of CLL and other CLPD. For instance, CD43 helps distinguish CLL from FL as it is positive in the former and usually negative in the latter. However, this marker cannot be used to distinguish CLL from other CD43-positive CLPD, such as MCL,39 CD200 is a glycoprotein belonging to the Ig superfamily that is consistently expressed in CLL, but is usually negative in MCL.40 Further to its diagnostic value, this antigen is being considered as a target for therapy in CD200+ tumours, including CLL. Furthermore, CD20 and CD52 expression should be included in the panel of markers since the monoclonal antibodies rituximab (anti-CD20) and alemtuzumab (anti- CD52) are generally used for therapeutic purposes. Finally, the receptor tyrosine-like orphan receptor one (ROR1) is an embryonic glycoprotein highly and specifically expressed on the membrane of malignant, but not normal B cells. In particular, ROR1 is highly expressed in CLL and hairy-cell leukaemia, intermediately expressed in MCL and DLBCL and scarcely expressed in FL.41 Moreover, ROR1 expression in CLL patients is not influenced by therapy. In marked contrast, B cells from healthy donors have no significant expression of ROR1.42 Several studies are currently testing the diagnostic and therapeutic use of monoclonal antibodies targeting this molecule.

Beyond its diagnostic and therapeutic value, immunophenotypic analysis has been shown to be useful for the estimation of prognosis by investigating the expression of CD38 and ZAP-70. Expression of CD38 and ZAP-70 are both predictors for an unfavourable outcome regarding treatment-free interval and overall survival. Although there is an overlap on the expression of these markers and the IGHV mutation status, some studies have demonstrated an independent prognostic value.43,44

Cytogenetics and Molecular Biology

In the context of CLL, cytogenetics and FISH tests are generally performed for prognostic purposes,2 as CLL does not display specific chromosomic aberrations. In contrast with what is observed in lymphoma, reciprocal balanced chromosomal translocations are extremely rare. However, chromosomal deletions and amplifications can be detected by FISH in up to 90 % of patients.2 FISH tests investigating the presence of t(11;14) (q13;q32), leading to cyclin D1 rearrangement, or t(14;18)(q32;q21), leading to BCL2 rearrangement, are useful for distinguishing CLL from MCL and FL, respectively.

The most frequent genetic abnormalities in patients with CLL are del(13q) as isolated abnormality (14 to 60 % of cases), del(11q) (10–32 %), trisomy 12 (11–18 %), del (17p) (3–27 %) and del (6q) (2 to 9 %), depending on the time-point at which the study is performed, and whether or not the disease is resistant to therapy.10 Del(17p) conveys dysfunction of the TP53 gene. Importantly, most patients with 17p deletion also have TP53 mutations on the other allele, but 2–5 % of patients present mutations of TP53 in absence of del(17p).45,46 Likewise, deletions and mutations of chromosome 11q may imply loss of the ATM function.47 Translocations are rare, but cases of t(14;19)(q32;q13) involving the IGHV gene and BCL3 loci, or even t(14;18)(q32;q21), can be observed. Of note, the use of newer mitogens, such as DSP30 and interleukin 2, has increased the detection of chromosomal abnormalities as detected by conventional cytogenetics.48,49 Clonal evolution and acquisition of new genetic abnormalities over the course of the disease is observed in 10–30 % of patients, particularly in those with unmutated IGHV genes50 and frequently involving subclones with driver mutations that expand over time.51

The application of next-generation sequencing techniques has revealed abnormalities that cannot be detected with either FISH or standard karyotyping. For example, around 5–10 % of patients can present mutations of NOTCH1 or of the RNA splicing factor SF3B1, which are associated with disease transformation, resistance to fludarabine therapy and short survival. Interestingly, NOTCH1 mutations and SF3B1 mutations correlate with trisomy 12 and del(11q), respectively. These newly discovered mutations could be integrated within Dohner’s classic hierarchical model and provide additional prognostic information.3

Cytogenetic abnormalities, using the hierarchical model proposed by Döhner et al.,2 correlate with several clinical and biological features which can be summarised as follows:

- 13q deletion (isolated): early, non-progressive disease, good prognosis.

- 11q deletion and/or ATM mutations: younger, male patients with bulky lymphadenopathy and aggressive disease. Poor response to monotherapy and short progression-free survival. It is associated with SF3B1 mutations.52

- 17p deletion and/or TP53 mutations: progressive disease resistant to conventional therapy.

- Trisomy 12: atypical morphology (e.g. increased percentage of prolymphocytes) and immunophenotype (e.g. FMC7 positivity, CD5 negativity, strong surface Ig and CD38). Association with NOTCH1 mutations, particularly when trisomy 12 is not part of a more complex karyotype.53

- Deletion 6q: blood lymphocytes presenting lymphoplasmacytoid features.

Conclusion

CLL is the most common CPLD in the developed world. The diagnosis of CLL is made by the combination of clinical and laboratory characteristics. Morphology and immunophenotype are the initial, and usually sufficient, diagnostic investigations. In cases with morphological atypical features, additional tests such as molecular genetics and/or histology are required to confirm the diagnosis. Some other markers, such as CD38 and ZAP70 expression, are also useful for prognostic purposes.

A monoclonal population immunophenotypically identical, or similar, to that found in CLL or other CLPD can be detected in up to 3–10 % of healthy people. However, only those with ‘clinical’ MBL behave as early stage (Rai 0) CLL and need to be clinically followed, while avoiding cumbersome and anxiety-triggering medical examinations in those with minute monoclonal populations.