Head and neck cancer encompasses tumours of different origins and types. Over 90 % of them are squamous cell carcinomas arising the epithelium of the upper aerodigestive tract, extending from the and oral cavities, down to the larynx and hypopharynx. Among the various clinical and pathological prognosticators, the presence of cervical nodal metastasis is the most important factor that adversely affects survival after treatment. Cancers with N0 classification on presentation usually have excellent cure rates with either surgery or radiotherapy, while those with regional metastases on presentation have significantly worse survival. Over the past decades, treatment of the neck has received much attention and has become one of the most debated topics in the field of head and neck oncology. Traditionally, treatment of the neck in patients with clinically evident nodal metastasis has been surgical. Nowadays, chemoradiation (CRT) has been utilised more and more as the primary treatment, aiming at organ and function preservation. Neck dissection for residual or recurrent nodal metastasis is associated with increased incidence of potentially severe complications.1 It exacerbates the chronic effects of radiation, including subdermal fibrosis, neck stiffness, pain and diminished shoulder mobility and quality of life.2 In this article, we will address some of the current controversies in the surgical management of isolated nodal recurrence after head and neck cancer treatment.

Assessment of Nodal Response

to Chemoradiation Surgery after CRT should be reserved for patients with residual viable cancer. There is general agreement that patients with less- thancomplete response should undergo neck dissection to eliminate potential residual viable nodal tumour.3,4 It is also accepted that patients with complete response of N1 disease do not require neck dissection.5,6 The main controversy lies within the N2 to 3 disease group, whereby there is uncertainty as to how well clinical complete response predicts the eradication of tumours. The best imaging modality for the assessment of tumour response after CRT and the ideal timing to perform such investigation remains under investigation. Ideally, the imaging should allow a timely identification of patients who will benefit from post-irradiation neck dissection while avoiding surgery in those with complete response.

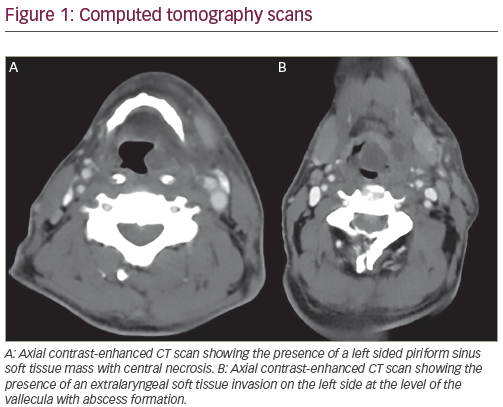

Traditionally the response evaluation after CRT was performed by clinical examination and computed tomography (CT) scan 6–8 weeks post treatment. Some reports in the literature advocate that CT scan after CRT is the imaging of choice. Clayman et al.7 showed no recurrence in 29 observed oropharyngeal cancer patients with negative CT scans after CRT. Similarly, Corry et al.8 reported no nodal relapse in 60 observed patients. Liauw et al.9 found one neck recurrence out of 32 patients with complete response on CT scan after radiotherapy. However, the accuracy of CT assessment of complete response was disappointing in some experiences, reporting high rates of viable tumour (30–40 %) in neck specimens from patients who had a radiological complete response.10

Despite the potential ability of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) scan to distinguish viable tumour cells, current evidence show that it is not sensitive enough to allow early detection of residual tumour after CRT. Rogers et al.11 performed PET scans 1 month after CRT and found that six of seven patients with a negative scan had residual cancer at neck dissection. Similarly, Gourin et al.12 and Greven et al.13 reported an unacceptably high proportion of patients who had residual nodal tumours despite a negative PET scan, which was performed 8 to 10 weeks and 1 month after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, respectively. When performed 10–15 weeks after treatment, however, some found a better correlation between the PET scan results and the pathological nodal status.14

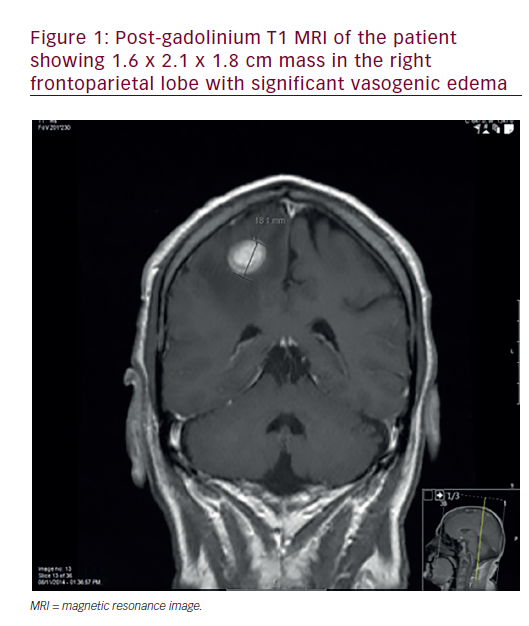

Recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have provided further biological information: diffusion-weighted MRI is a non-invasive imaging technique that measures the differences in water mobility of different tissue microstructures. Water mobility is likely influenced by cell size, density and cellular membrane integrity and is quantified by means of the apparent diffusion coefficient. This coefficient in malignant lymph nodes is reduced because of the increased density of tumour cells.10 Vandecaveye et al.15 evaluated response in 29 patients 3 weeks after the completion of radiotherapy. Results showed positive predictive value of 70 % and negative predictive value of 96 % for adenopathy per neck side. He also reported a sensitivity of 76 % for diffusion-weighted MRI as opposed to 7 % for conventional MRI. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is another promising imaging sequence that provides information regarding tumour blood flow and permeability.16 Reports indicate that this technique may be useful to predict both intra-tumour hypoxia and tumour response.

Role of Planned and Salvage Neck Dissection

The concept of planned neck dissection was first used in 1970s to indicate an elective neck dissection performed to a clinically undetectable disease.10 Many centres worldwide practise planned neck dissection after radiotherapy because historically the complete response rates for large volume nodal disease to radiotherapy alone was low and the outcome of subsequent salvage was poor. Mabanta et al. studied 51 patients with neck recurrence after primary radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and he found that 35.3 % of the patients had unresectable disease.17 The 5-year regional control after neck dissection was 9 % and the overall absolute and cause-specific survival rates were 10 % at 5 years. With the global trend towards organ and function preservation, CRT is gradually gaining popularity over surgical treatment in the management of head and neck cancers. Advances in radiation delivery, such as intense-modulated radiotherapy and altered fractionation regimens, have led to development of concurrent CRT and, consequently, enhanced disease control. As a result, the role of planned neck dissection becomes less well-defined.10

It is widely accepted that early planned neck dissection is recommended for patients with clinically partial response after CRT. For patients with clinically complete response, pre-emptive neck dissection in patients with initially low volume (N1) nodal metastasis is not necessary. However, the role of planned neck dissection in patients who present initially with high volume (>/= N2) neck disease is controversial.

Neck dissection after CRT is technically demanding and is associated with a higher rate of complications. Such adversities can potentially be minimised by performing the surgery between 4 to 12 weeks after the completion of radiotherapy. During this period, surgery is technically easier, and conservation procedures are usually possible due to limited fibrosis. By contrast, salvage neck dissection performed after this window period is associated with significantly increased risk and severity of surgical complications18 Moreover, conservative surgery is usually impossible and more radical surgery is more frequently required because of the extensive fibrosis and widespread infiltration by cancer. The extent of such surgery would then translate into a negative impact on quality of life.

The oncological outcome of salvage neck dissection was shown to be poor.19–21 Recently, van der Putten et al.22 studied 540 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck region who received chemoradiotherapy as the primary treatment. Subsequent regional residual or recurrent disease was found in 129 patients. Among them, 68 patients were considered inoperable. The 5-year regional control and overall survival rates after salvage neck dissection was 79 % and 36 %, respectively. Significant prognostic factors for overall survival after surgery were the resection margins and the status of residual disease after CRT.

In the advanced nodal disease group, there is a possibility of metastatic aggressive disease. Nobuhiro et al.23 demonstrated that cervical lymph node metastasis at level V was an indicator of distant metastasis.

Proponents of planned neck dissection questioned the accuracy of post-CRT clinical and radiological surveillance. Viable tumour (22–29 %) could be demonstrated despite negative radiological findings.10 Moreover, morbidity of surgery is minimal if performed during the 4 to 12-week window. In a long-term, follow-up analysis from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation of N2–3 patients treated with CRT, regional control at 5 years was significantly inferior in patients not undergoing neck surgery compared with those who underwent neck dissection.24 Argiris et al.25 have also concluded that the 5-year locoregional control and neck progression-free survival rates were significantly higher in patients with neck dissection compared with those without: (88 % versus 74 %; p=0.02), (99 % versus 82 %; p=0.0007), respectively. Lavertu et al.26 have also showed that adding neck dissection minimised neck recurrence (p=0.05).

Opponents argue the negative impact of neck dissection on quality of life, absence of certain overall survival advantage and the possibility of metastatic aggressive disease.10,23 Thariat et al.27 studied a cohort of 880 patients with T1–4, N1–3 squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, larynx or hypopharynx treated with CRT and reported that the 5-year actuarial regional control rate for patients with complete response was 92 %, so there is little justification for planned neck dissection in this group of patients. In patients with less than complete response, those with planned neck dissection performed had better regional control than those who were observed (5-year actuarial regional control, 90 % versus 76 %; p<0.001).

The Extent of Neck Dissection

The traditional philosophy of neck dissection for cervical nodal metastasis was to remove lymph node groups in all five levels. More recent reports have demonstrated the efficacy of selective neck dissection.28–32 It involves the extirpation of lymph nodes in the neck with preservation of at least one nodal level. Only regional lymph nodes that have clinical evidence of tumour metastasis are removed, while sparing uninvolved lymphatic and non-lymphatic structures, including the sternocleidomastoid muscle, internal jugular vein and the spinal accessory nerve. The rationale of the more conservative approach is that the pattern of nodal metastasis in the cervical region is predictable and that the neck levels that were uninvolved prior to treatment are unlikely to harbour residual tumour cells after CRT. Furthermore, primary CRT would achieve a similar objective in sterilising occult disease in low-risk levels so that post-treatment selective neck dissection targeting only residual gross disease in high-risk nodal levels would be sufficient.28 Last but not least, the surgical side effects, including neck stiffness, shoulder dysfunction, cranial nerve palsy, etc. of selective neck dissection is considerably lower than that of the more radical type of surgery.29

The use of selective neck dissection after CRT was initially described in patients without residual disease.6–7 Subsequently, Robbins et al. and Stenson et al. reported their experience with the use of selective neck dissection in patients with initial N2–3 disease. They found that the neck failure rate after the conservative procedure was less than 5 %,30,34 which was similar to that after more extensive surgery.35 Similar results were reported in other publications in the literature.32,36 Recently, Dhiwakar et al.37 studied 62 patients with squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region who were treated by primary CRT. Sixty-nine selective neck dissections were performed for clinically persistent nodal disease after a mean of 10 weeks after CRT. There was evidence of residual tumour in 46 % of the neck dissection specimens. Over a median follow up of 33 months, four patients (6 %) had recurrence in the neck, but only one occurred in the ipsilateral target neck, demonstrating the safety and efficacy of the more conservative neck dissection in such setting.

Based on the satisfactory results of selective neck dissection, the efficacy of super-selective neck dissection after CRT, which is defined as the removal of two or less contiguous levels of cervical lymph nodes, is being investigated. It is advocated for patients who have small, residual single-level adenopathy. Robbins38 et al. studied 177 patients after intraarterial cisplatin and radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Among 89 patients with residual neck disease, 73 patients had clinical residual adenopathy involving only one neck level. Fifty-four patients eventually underwent neck dissection and the pathology result showed that only two patients had disease extending beyond the single neck level, and one of them had disease in a contiguous neck level and the other patient had disease in a non-contiguous level. They concluded that super-selective neck dissection was feasible for patients after CRT with persistent nodal disease that was confined to one level. Goguen et al.39 reported a 95 % negative predictive value for CT for cervical nodal status after CRT, and suggested that it could provide a road map for designing super-selective neck dissection in partial response patients with limited residual disease. Further studies are required to demonstrate the efficacy of such procedure before its routine use can be advocated.

Conclusions

Management of the neck after organ-preserving CRT for cancers in the head and neck region is important. Early CT and/or diffusion-weighted MRI scans after the completion of CRT appears to be useful in assessing the tumour response to treatment, especially for patients presenting with N2–N3 disease. With improving chemoradiotherapy and diagnostic studies, pre-emptive neck dissection is not necessary in patients with clinically complete nodal response. In patients with partial response, however, early planned neck dissection is recommended. In patients with limited tumour volume, early results showed that conservative surgical approaches including selective neck dissection or even superselective neck dissection may achieve a satisfactory tumour control without causing unnecessary surgical morbidities.