Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most prevalent adult leukemia with an estimated 18,960 new cases diagnosed in the US in 2016.1 The past few years have witnessed major advances in the treatment of CLL with several new drugs receiving US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in both the frontline and relapsed/refractory setting leading to improvement in overall survival (OS). The availability of several active and relatively well-tolerated agents has raised questions on the optimal drug sequence, duration, and tailoring therapy based on the underlying disease biology. With effective drugs in the previously considered poor prognostic individuals, there is also a need to redefine the prognostic criteria. Several guiding principles have already been established including the management of early asymptomatic disease with observation alone. Indications for treatment of untransformed disease include at least one of the following based on The International Workshop Group on CLL (IWCLL) 2008 guidelines:2

• Progressive marrow failure due to CLL infiltration as evidenced by worsening cytopenias

• Massive (>6 cm below costal margin) splenomegaly with symptoms

• Bulky (>10 cm) or symptomatic lymphadenopathy

• Progressive lymphocytosis

• Autoimmune cytopenias unresponsive to immunosuppressive therapy

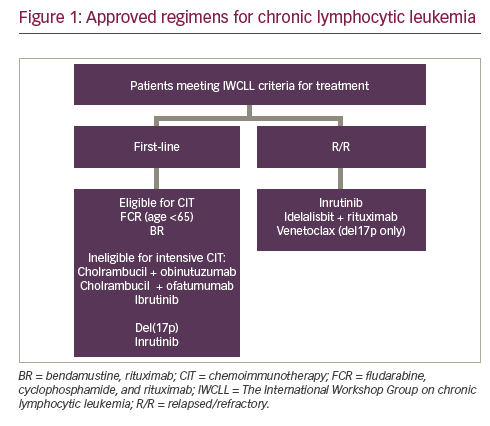

• Presence of B symptoms or significant fatigue (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status [ECOG PS] of 2 or more related to disease). In those that meet criteria for treatment, important considerations include: patient age, performance status, comorbidities, and presence of chromosomal aberrations. Recent advancements in the understanding of disease biology have highlighted the importance of several potentially targetable pathways contributing to disease pathogenesis such as aberrant activation of BCR signaling pathway, anti-apoptotic BCL2 pathway, and the role of the microenvironment. These novel agents have expanded the repertoire for patients ineligible for chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) due to age or comorbidities and those with poorly responsive disease (high risk genomics such as del[17p]). This review aims to outline the role of standard CIT, targeted agents and ongoing studies of novel agents defining the present landscape of CLL drug treatment. Currently approved therapies and general treatment approach in the first-line and relapsed/refractory (R/R) settings are summarized in Figure 1.

Chemoimmunotherapy regimens in CLL—fit patients with no major comorbidities

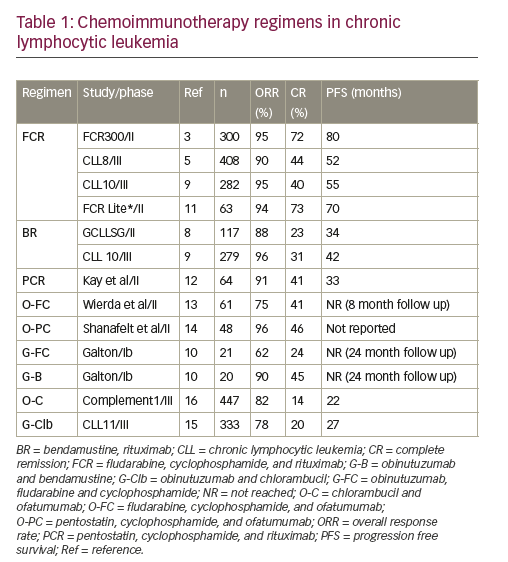

CIT regimens combine chemotherapeutic agents with a CD20 antibody like rituximab, ofatumumab and obinutuzumab. CIT regimens such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) have been the mainstay of frontline CLL therapy especially in the young, fit individuals. At present, there is no proven benefit to early treatment of patients with CLL. Patients who meet criteria for treatment need to be stratified further based on fitness assessment (age, organ function and performance status) and biological risk (most importantly TP53mutation and /or del[17p]) for treatment decision. Table 1 summarizes the trials comparing different CIT combinations incorporating cytotoxic chemotherapy in combination with a CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) that are recommended in the young and elderly fit patients.

FCR is the regimen of choice in young (<65 years), fit patients without evidence of TP53 disruption based on the FCR300 and CLL8 trials. In FCR300,3 a single arm phase II study received FCR as first line treatment. At a median follow up of 6 years, complete remission (CR) was seen in 72% with an overall response rate (ORR) of 95%. Six-year overall survival (OS) rate was 77% and progression free survival (PFS) rate was 51%. Recently updated results at a median follow up of 12.8 years show a median PFS of 6.4 years. Considering unmutated (UM) and mutated (M) immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) gene status, IGHV-UM and IGHV-M, 12.8 year PFS was 8.7% and 53.9% respectively. Importantly, in the IGHV-M subgroup there were no relapses after 10.4 years represented by a plateau on the PFS curve.4 A larger phase III study, the CLL8 trial compared FCR with FC. FCR was associated with a superior ORR (90% versus 80%), CR (44% versus 22%), 3-year PFS (65% versus 45%), and 3-year OS (87% versus 83%). FCR was associated with a higher rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia.5 Long-term follow up studies after FCR treatment have revealed durable responses in patients with IGHV-M CLL and those without del(17p) or del(11q).4,6,7

Bendamustine and rituximab (BR) was evaluated in a phase II study with 117 patients in the front-line setting showed an ORR of 88% and a CR rate of 23%. At a median follow up of 27 months, the median (m)-PFS was 33.9 months. A quarter of the patients in this study were >70 years and their m-PFS

was similar to younger patients despite a lower ORR in this age group.8 Further in the randomized phase III CLL10 trial, BR was compared with FCR in the front-line setting.9 This was a non-inferiority trial with PFS as primary endpoint and excluded patients with del(17p). The final analysis of 561 patients included 282 patients in the FCR arm and 279 in the BR arm. At a median follow up of 37.1 months, the m-PFS was 55.2 months and 41.7 months in the FCR and BR arms respectively. OS was not different between the two arms. The FCR arm was associated with more grade 3/4 neutropenia and infections especially in patients older than 65 years. There was no difference in PFS in the subgroup of patients >65 years. In addition, post-hoc analysis, favored the use of FCR in patients with IGHV-UM (p=0.017) and del(11q) (p=0.0002) CLL. Due to a lower rate of complications in older patients, BR is a reasonable front-line choice in fit CIT eligible patients >65 years of age. Several additional CIT regimens were tested in the frontline setting and are summarized in Table 1.10–14

Less intensive regimens—older patients with comorbidities

For elderly or patients, otherwise unfit for the above mentioned “intensive” CIT regimens and in the absence of del(17p), several different options have emerged in the past few years as frontline therapy. The current standard regimen in this setting is the combination of chlorambucil with an anti-CD20 antibody.15 A phase III (COMPLEMENT-1) study included 447 patients who were ≥65 years of age and evaluated chlorambucil versus chlorambucil + ofatumumab (O-C). At a median follow up of 28.9 months, the m-PFS was 22.4 months in the combination arm, versus 13.1 months in the chlorambucil arm. The ORR and CR rates were 82% versus 69%, and 14% versus 1% respectively favoring the combination.16 The study however, lacks head-to-head comparison with rituximab likely because at the time of trial design, chlorambucil as a single agent was an acceptable comparator.

The phase III CLL11 trial randomized 780 patients to chlorambucil alone versus chlorambucil + rituximab (R-C) versus O-C in a 1:2:2 fashion. The O-C arm was superior to R-C in terms of PFS (median, 26.7 versus 16.3 months), ORR (78.4% versus 65.1%), CR (20.7% versus 7.0%), and minimal residual disease (MRD).15 Infusion related reactions were notably higher in patients receiving O-C, 20% as compared with 4% in the R-C arm. Based on these two trials, the combination of chlorambucil with ofatumumab or obinutuzumab are FDA approved for front-line therapy of CLL patients.

Therapies directed against very-high risk CLL in the pre-kinase era

Patients with very-high risk CLL such as those with del(17p) or TP53 gene mutation have poor response to the above mentioned chemotherapy as such agents are dependent on the DNA damage pathway for their cytotoxicity.3,5,17 For example, the CR rate with FCR in this high risk population in the CLL8 trial was 5% with a m-PFS of 11.3 months.5 Similarly, in patients treated with BR the m-PFS was 7.9 months with no patient achieving a CR.8 Alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 antibody was evaluated in CLL as first-line therapy in a phase III trial but failed to improve response in del(17p) patients with a median PFS of 10.7 months in this population.18 The combination of alemtuzumab and steroids was evaluated further in the CLL206 trial with a m-PFS of 18.3 months and in another trial with this combination (CLL20), the m-PFS was 32.8 months. The improved outcome was attributed to the use of allogeneic stem cell transplantation as consolidation.19,20

The combination of Rituximab with high dose methylprednisolone (HDMP) was tested in patients with fludarabine refractory disease and found to have an ORR of 93% with 36% attaining CR.21 The dosing schedule was three cycles of rituximab (375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks) in combination with HDMP (1 gm/m2 daily for 5 days). While this regimen was associated significant steroid-related side effects including fluid retention and transient hyperglycemia, it was minimally myelosuppressive making it an option in otherwise high risk and/or elderly patients. This combination was tested in the front line setting in 28 patients, with 3 days of HDMP to minimize toxicities.22 The ORR was 96% and CR was 32%. The m-PFS at 3-year follow up was 30 months. While these two studies included few patients with del(17p), Pileckyte et al. reported their results with this combination in R/R high risk CLL with 29 patients including 13 with del(17p). The ORR in del(17p) in the R/R setting was 69%. The regimen used in this study was more intense with 5 days of HDMP and each cycle had two doses of Rituximab up to a total of six cycles.23 Overall, with these studies, the possibility of using rituximab with HDMP is an option in the high-risk cytogenetics group especially in those with poor bone marrow reserve.

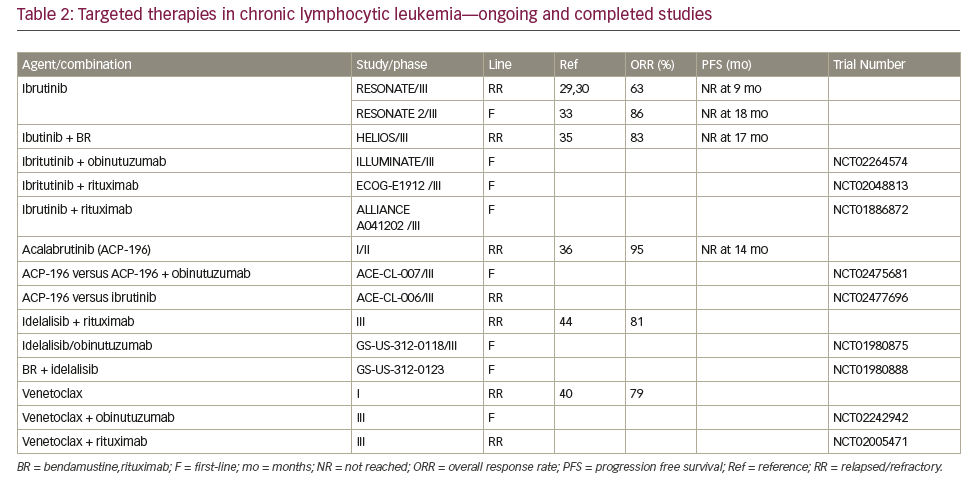

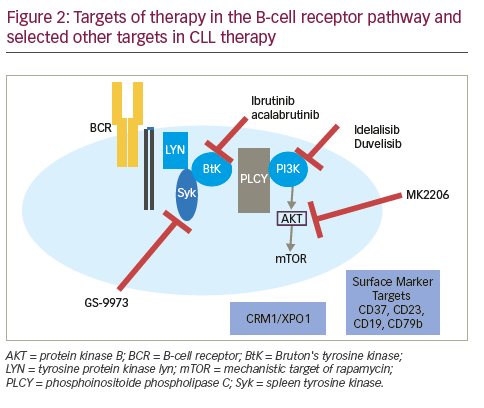

Therapies targeting the CLL-signaling pathways The B-cell receptor (BCR) is important in the pathogenesis of CLL mediating the signal for cell division. Furthermore, the differential responsiveness of BCR to stimuli is implicated in the differences in prognosis of IGHV-M and IGHV-UM.24 Apart from BCR signaling, the BCL2 pathway has become a target in CLL. The effectiveness of these agents in patients with del 17p or TP53 mutations has been encouraging. Table 2 summarizes completed and ongoing studies of targeted therapies in CLL.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase that belongs to Tec family of kinases. It has an important role in BCR signaling leading to downstream activation of pathways important for CLL cell survival including NF-κB and PI3K. It also contributes to CLL pathogenesis by being involved in B-cell migration and adhesion.25–27 Ibrutinib is an oral selective and irreversible inhibitor of BTK that acts by forming a bond with cysteine-481 of BTK.28 Ibrutinib is FDA approved for patients with R/R CLL and those with del(17p) CLL. In a large phase III (RESONATE) trial in 391 patients (127 harbored a del[17p] with R/R CLL, ibrutinib was associated with a 63% response rate [70% investigator assessed]). At a median follow up of 9.4 months, the PFS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm and 8.1 months in the ofatumumab arm. The 1 year OS was 90% in the ibrutinib arm and 81% in the ofatumumab arm.29,30 In a small phase I/II study in elderly patients with a median age of 71 years, O’Brien et al found an ORR of 71% (95% confidence interval [CI] 52.0–85.8) with 13% CR rate at a median follow up of 22 months. Six percent of patients had del(17p).31 At 3-year follow up, the ORR was 84%, with 23% attaining CR. The 30-month PFS was 96%, and OS was 97%.30 Another phase III study evaluated response of ibrutinib in 51 patients with disruption in TP53 pathway (47 with del(17p) and 4 with TP53 mutation without del(17p) including 35 patients with previously untreated CLL). The ORR in previously untreated patients with 97% and R/R CLL patients was 80%. The CR rate in untreated patients was 12% with a median time to CR of 48 weeks and 2 year PFS was 91%.32 These studies have led to the acceptance of ibrutinib as first line treatment agent of choice in CLL patients with TP53 mutation and/or del(17p). RESONATE 2 is a phase III trial that tested ibrutinib as first line treatment in patients 65 years or older without del(17p). Treatment naïve patients, requiring therapy were randomized to receive ibrutinib or chlorambucil. At a median follow up of 18.4 months, the ORR was 86% in the ibrutinib arm compared with 35% in the chlorambucil arm. Ibrutinib resulted in a higher m-PFS (not reached versus 19 months) and 24-month OS (98% versus 85%).33 Lymphocytosis after the initiation of treatment with BTK inhibitors including ibrutinib is common and self-limited, often resolving within 6–9 months of starting treatment. It is not associated with any clinical adverse effects or adverse clinical outcome.34

In a recent study, CIT (BR) was compared with bendamustine, rituximab, and ibrutinib in a phase III trial (HELIOS). The ORR was 83% compared with 68% in the group treated with BR alone. At the time of analysis 79% of patients receiving Ibrutinib were in remission versus only 24% in patients who did not. At a median follow up of 17 months, the m-PFS was not reached in patients receiving ibrutinib with CIT whereas the m-PFS was 13.2 months in patients treated with BR.35 The major critique concerning this trial was the question if chemotherapy added any benefit to ibrutinib, as the combination therapy yielded similar results that were comparable to single agent ibrutinib in prior studies. In an ongoing frontline CLL phase III trial in elderly patients (>65 years), otherwise ineligible for chemotherapy are being randomized to receive either obinutuzumab and ibrutinib or obinutuzumab and chlorambucil (ILLUMINATE study; NCT02264574). Other studies evaluating ibrutinib combinations include untreated CLL/SLL randomized to either FCR or ibrutinib and rituximab in a phase III trial (NCT02048813); and NCT01886872, a multi-arm phase III trial with Ibrutinib alone, Ibrutinib and rituximab or BR in older patients in the front-line setting.

Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) is a second-generation, selective, irreversible inhibitor of BTK. It has rapid oral absorption and higher selectivity with the absence of irreversible inhibition of off target kinases, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), tyrosine kinase expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (TEC), and interleukin-2-inducible T-cell kinase (ITK). In a study of 60 patients, at a median follow-up of 14.3 months, the ORR overall response was 95% with 5% having stable disease. Thirty percent of patients had del(17p) and experienced an ORR of 100%. Most common side effects were headache, diarrhea, and weight gain and there were no cases of atrial fibrillation have been reported to date.36 Ongoing phase III trials include acalabrutinib in isolation or combination in the first-line (NCT02475681) and in R/R CLL (NCT02029443; NCT02477696). Other novel BTK inhibitors in development include ONO-4059 which was well tolerated in its phase I study and has an ORR of 84% across the board including in those with del(17p).37 CC-292 (spebrutinib) showed an ORR of 63% in its phase I study.38

BCL2 inhibitors in CLL

Like several other hematologic malignancies, BCL2 pro-survival protein family is over expressed in CLL and mediates CLL cell survival. This led to the development of BH3 mimetic agents that antagonize BCL2.39 Venetoclax is an oral, selective BCL2 inhibitor. It is FDA approved for treatment of R/R del(17p) CLL. As monotherapy, venetoclax showed an ORR of 79% and CR rate of 20% at a median follow up of 15 months. Median PFS was 18 months.40 In a phase II multicenter study of 107 relapsed patients harboring del(17p). At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, ORR was 79.4%.41 The most common grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia (40%), infection (20%), anemia (18%), and thrombocytopenia (15%). Given the risk for tumor lysis syndrome, the drug is administered via a weekly dose ramp-up schedule over 4–5 weeks followed by a continuous dosing of 400 mg/day until disease progression. In combination with rituximab, at a median follow-up of 28 months, the ORR was 86%, including a complete response in 51% of patients. Fifty-seven percent of patients had negative MRD.41 With these impressive results in R/R CLL, venetoclax is currently being studied in the front line setting where patients with CLL and a high Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score are being randomized to venetoclax + obinutuzumab or O-C (NCT02242942). In patients with R/R CLL, a phase III trial comparing venetoclax + rituximab versus BR is ongoing (NCT02005471). Based on preclinical evidence of synergy, a phase II study evaluating venetoclax and ibrutinib in R/R or untreated high risk CLL is ongoing (NCT02756897).42

PI3 kinase inhibitors

PI3Kδ pathway is involved in normal B cell activation and survival. Hyperactivity of this pathway plays a role in the pathogenesis of several B cell malignancies including CLL.43 idelalisib is an oral selective PI3Kδ inhibitor that has activity in CLL and is approved in the R/R CLL setting in combination with rituximab. In a multicenter phase III study, idelalisib and rituximab was compared with rituximab alone. Patients receiving combination therapy had improved rates of overall response (81%), and OS at 12 months (92% versus 80% p=0.02).44 The most commonly reported adverse events reported include; fatigue (24%), diarrhea (19%), transaminitis (35%). Neutropenia (3%), and pneumonitis (4%) were other serious adverse events. In a prespecified subgroup analysis, patients with either 17p deletion or TP53 mutation had improved PFS with idelalisib and rituximab. Data in the frontline setting is limited. Ongoing frontline combination therapies that included idelalisib were halted due to concern for toxicities.

Several other agents that target the PI3Kinase pathway are currently under evaluation. Duvelisib (IPI-145), a novel oral PI3Kδ and PI3K-ϒ inhibitor was evaluated in a phase I study in R/R CLL patients. The rate of grade 3/4 neutropenia was 42% and transaminitis of 9%, while the ORR was 58% with 2% of the 55 patients achieving a CR.45 While duvelisib was seen to overcome ibrutinib resistance due to C481S mutation and has been seen to have activity in ibrutinib refractory disease, its recent development as a CLL agent has been paused by its source pharmaceutical company.46–48 TGR- 1202 is a second generation oral PI3Kδ inhibitor being tested in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) including CLL, in 20 CLL patients the ORR was 63%. Most common grade 3/4 toxicities were cytopenias, dyspnea, rash, and fatigue. There was lower incidence of transaminitis, colitis, and pneumonia.49 It has been studied in combination with ublituximab, a novel, chimeric mAb targeting a unique epitope on the CD20 antigen in R/R CLL, an ORR of 83% was seen.50. PI3-Kinase inhibitors are effective in CLL therapy. Their unique toxicities although concerning and may have been associated with early treatment discontinuation, vigilance in symptom monitoring an appropriate management is prudent for the success of this therapy.

Immunomodulators and other immune based treatments in CLL

Lenalidomide is by far the most common immunomodulator (IMiD) that has been studied in CLL. It was found to possess moderate activity in R/R CLL.51–53 Badoux et al. reported outcome on 60 patients (>65 years). At a median follow up of 29 months, the ORR was 65% with a CR rate of 10%. Estimated 2-year PFS was 60%. The starting dose in this study was 5 mg/ day with an escalation by 5 mg/cycle up to a maximum of 25 mg. The median dose in this study was 5 mg/day.54 Chen et al. reported outcome on 25 patients with a median age of 60 years. With the initial starting dose of 10 mg, two patients had serious adverse events including tumor lysis and sepsis. The protocol was amended to have a starting dose of 2.5 mg up to a target dose of 10 mg, allowing escalation up to 25 mg in non-responders. The median dose administered was 15 mg. ORR seen in this study was 56%. In the follow-up analysis, the ORR was 72% with a CR of 20%. The 3-year PFS was 65% and OD was 85%.55,56 Treatment with lenalidomide is associated with tumor flare in more than half of the patients and this is clinically seen as a sudden enlargement of lymph nodes accompanied by redness and tenderness. This change is benign and attributed to an “immune activation” response.57 Ongoing combination studies of lenalidomide include those with obinutuzumab (NCT02225275, NCT02371590) and a triple combination with rituximab and ibrutinib in R/R CLL (NCT02200848). Although active, lenalidomide does not have an FDA approved indication in CLL therapy. Lenalidomide has been evaluated in the maintenance setting in newly diagnosed high risk patients following CIT with an improvement in PFS.58

Ramsay et al. demonstrated that T cells from CLL patients have higher expression of inhibitory immune checkpoint molecules such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) and have impaired immune synapse function and thereby reduced cytotoxicity. CLL cells express the corresponding ligands both PDL1 and PD-L2.59–61 Furthermore, there is evidence for T cell exhaustion in CLL.62 Preclinical studies in a T-Cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1 (TCL- 1) mouse model have shown evidence of the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in mice where this restored the immune synapse function and prevented the development of CLL with early intervention. Several clinical trials are examining the role of this in humans (NCT02420912, NCT02332980). Based on preclinical evidence of synergy with Ibrutinib, Ongoing trials are examining the role of this combination in CLL. Jain et al. presented the preliminary results of this combination in R/R CLL or Richter transformation in 12 patients with evidence of activity in this patient population.63

A detailed discussion of CAR-T cell therapy in CLL is beyond the scope of this review but briefly, CD-19 CAR-T cell therapy has been found to have an ORR of 45–57% in various studies.64,65

Novel pathways and drugs

Beyond immunotherapies, novel pathways of interest have gained interest as targets for CLL therapy. Antibodies against cell surface markers such as CD37, CD23, CD19, CD79b, and selective inhibitors of nuclear exporter of tumor suppressors, CRM1/XPO1, are under evaluation in clinical studies based on preclinical data.66–74 Stimulation of the BCR results in activation of the associated spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), which mediates downstream signaling, and amplification of response. Syk is therefore a viable target and GS-9973 (entospletinib) is under development as a selective Syk inhibitor.75,76 A phase II study in R/R CLL showed an ORR of 61%, and serious adverse events included dyspnea, pneumonia, fever and febrile neutropenia76 CD37 is a cell surface marker seen on mature B cells and is expressed on CLL cells at a high level.74 Otlertuzumab (TRU-016), a novel humanized anti-CD37 protein has been studied in a phase I study in R/R CLL and also in combination with rituximab.77,78 An anti-CD37 antibody-drug conjugate IMGN529 is being studied in R/R CLL in a phase I study (NCT01534715).79 Another CD37 directed therapy is BI 836826 an anti-CD37 mAb which is being studied in a phase I study (NCT01296932).80 Another cell surface target CD23 is expressed on CLL cells and functions as an immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor. Drugs targeting CD23 include a mAB, lumiliximab, that failed to show added benefit when combined with FCR.81 MEDI-551 is a CD19 antibody that has been tested in R/R CHL and there are ongoing studies in combination with bendamustine (NCT01466153). Another CD19 mAb XmAb5574 (MOR208) with activity in a phase I study, is being tested in combination with lenalidomide (NCT02005289).82 Based on preclinical evidence of activity,83 selective inhibitors of nuclear export that target XPO-1, which showed activity in CLL in a phase I study, is being tested in combination with ibrutinib in R/R CLL (NCT02303392). Preclinical data suggested that the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis is important in CLL and plays a role in the homing and retention of the malignant CLL cell in tissues including the bone marrow. Small molecule CXCR antagonist, plerixafor was hypothesized to improve the sensitivity to rituximab by mobilizing CLL cells and was tested in the R/R setting (NCT00694590). Preliminary results from this phase I study showed that the combination was well tolerated and showed an ORR of 36% (all partial response) in 14 patients.84 In addition to these drugs under study in clinical trials in CLL, preclinical studies have outlines several additional pathways that can be targeted for therapy including CD38, nuclear factor-κB and MYD88 (beyond lenalidomide and ibrutinib), surrogates of zeta chainassociated protein kinase 70 (ZAP 70), TCL-1, induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein (Mcl-1), CD49d (possibly also affected by ibrutinib and idelalisib), translocation-associated notch protein (TAN-1) (NOTCH1), and Splicing factor 3B1 (SF3B1).85

Evolving cost burden of CLL with emerging therapies

As targeted therapies are being used both in the first-line and relapsed CLL setting and resulting in longer survival in many patients, with prolonged duration of therapy, it is important to acknowledge the economic impact of these advances in treatment. Using a Markov micro-simulation prediction model, Jain et al. outlined the projected increase in prevalence and total cost of CLL treatment from 2011–2035.86 They predict that compared with $0.9 billion in 2011, the annual cost of CLL treatment is projected to increase to $3.5 billion in 2025. Shanafelt et al. have raised similar issues in this context taking into account the cost burden of ibrutinib and idelalisib therapy.87 This is of concern as this can potentially affect the access and adherence to the prescribed drugs and raises the need for sustainable pricing of these drugs.

Conclusion

In view of the fortunate advances in the field of CLL, the treatment algorithms in this disease are rapidly changing. These advancements have led to a change in the challenges of CLL treatment from having too few options to now deciding on the optimal sequencing and duration of the many available options. When available, participation in clinical trials should be considered in both front-line and R/R CLL. With several approved therapies in hand, patient factors such as: performance status, comorbidities, cytogenetic risk, and toxicity profile of drugs should be taken into consideration before deciding on the best option. At present, there is no role of starting treatment in the asymptomatic patients and criteria from IWCLL 2008 guidelines remain important in deciding who needs treatment.