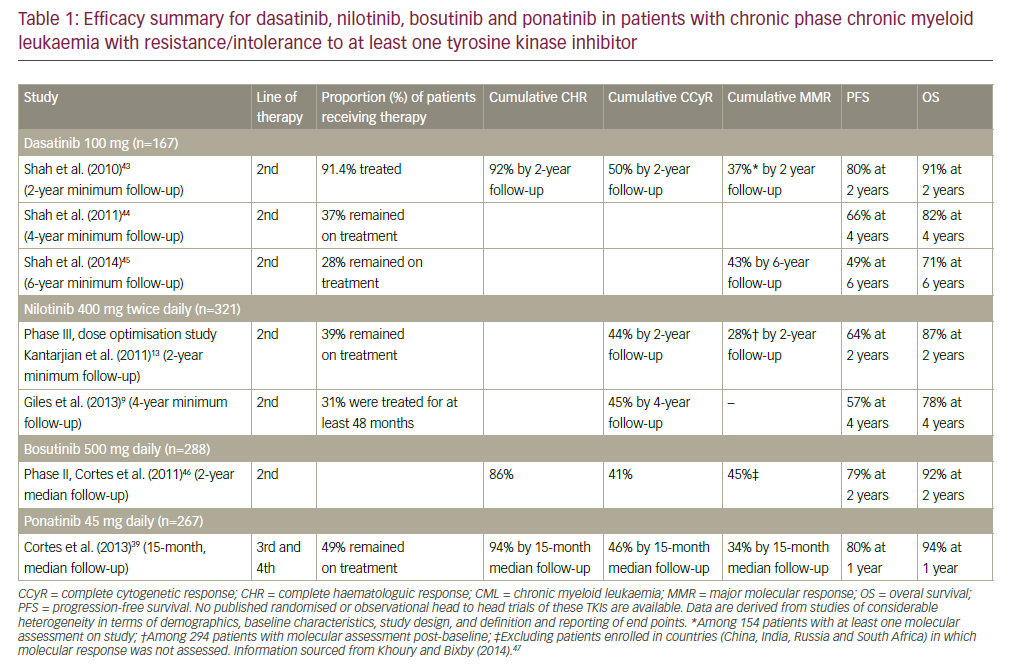

Clinically, CML progresses through three distinct phases of increasing refractoriness to therapy: chronic phase (median duration three to four years; median survival five to seven years with interferon), accelerated phase (median duration three to nine months; median survival eight to 18 months) and blast crisis (median survival three to six months). Blast crisis can be either of myeloid or, less commonly, lymphoid phenotype.2

The first-line treatment of patients with newly diagnosed CML has been extensively described in the consensus guidelines published by the American Society of Hematology.3 The standard therapeutic options that were available before the imatinib era were recombinant interferon-alpha (IFN-?), chemotherapy with hydroxyurea, low-dose cytarabine or busulfan and allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation (BMT). Allogeneic BMT has been recognised as the only potentially curative treatment of CML.4 It is, however, available to only 15% of newly diagnosed patients who are considered young enough (usually 50 years or younger) and have a suitable sibling marrow.5

The probability of long-term survival when BMT is performed in the first chronic phase is approximately 60%. However, the procedure is still associated with a high rate of transplant-related mortality of 20–30%.4 Introduced in the treatment of CML 20 years ago, IFN-?-based regimens were considered the standard therapy for newly diagnosed patients in the chronic phase. IFN-? was the only drug that had been consistently shown to prolong median survival by approximately two years compared with chemotherapy. The major goals of IFN-? therapy are to achieve control of the peripheral blood counts (haematological response) and, subsequently, a major decrease in the proportion of marrow cells harbouring the Ph chromosome to less than 35% (described as major cytogenetic response – MCyR). The achievement of both a haematological response and an MCyR has repeatedly been shown to be associated with prolonged survival. In a large, randomised, phase III study, the combination of IFN-? with low-dose cytarabine (Ara-C) was shown to increase the rate of major cytogenetic response and prolong survival compared with IFN-? alone.6 Imatinib mesylate (formerly STI571) is a small-molecule protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitor that potently inhibits the activity of the bcr-abl tyrosine kinase, as well as two receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs): the receptor for stem cell factor (SCF) known as kit and the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF-R). Imatinib also inhibits cellular events mediated by signal transduction through kit and the PDGF-R.7

Soon after the demonstration of its anti-leukaemic effect, imatinib demonstrated encouraging activity in CML patients in the late chronic phase who were resistant to therapy with IFN-?, as well as in patients who were intolerant of such therapy.8

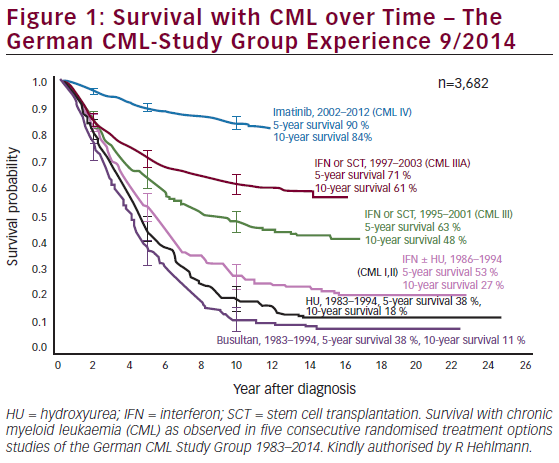

The data from the previous phase II studies in late chronic phase (study 0110), accelerated phase (study 0109) and blast crisis of CML (study 0102) clearly indicate that imatinib is effective in CML patients and that response to imatinib therapy improves the earlier treatment is started in the course of the disease (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the most recent update of these studies indicated that the responses achieved were durable.9

Based on the first phase I and II trials, imatinib was established as a safe and effective treatment for CML, which led to the regulatory authorities granting approval for the treatment of adult patients with CML in blast crisis, accelerated phase or chronic phase after failure of IFN-? therapy. However, it was reasonable to assume that the drug would also be effective in patients who are treated at an earlier stage of the disease. Moreover, inhibition of the bcr-abl kinase is most likely to have antileukaemic effects during the chronic phase of CML, since additional chromosomal abnormalities may drive the malignant process during accelerated phase and blast crisis.

Update of the Superiority of Standard-dose Imatinib as a Single Agent Over an IFN-?-based Regimen

In order to demonstrate the benefit of imatinib over the IFN-?-based regimen, it was decided to set up a large international study. This study (known as the IRIS study – International Randomized Study of IFN-? + Ara-C versus Imatinib) was carried out in newly diagnosed patients with CML chronic phase to compare the efficacy, safety and tolerability of imatinib administered as monotherapy with that of standard treatment with IFN-? plus Ara-C as the first-line treatment of the disease.

The IRIS study enrolled 553 patients in each arm between June 2000 and January 2001. It was the design of the trial to allow cross-over for patients who had no response, a loss of response, increasing white blood cell count, intolerance of treatment and failure to achieve major cytogenetic response (MCyR – less than 35% Ph chromosome positive bone marrow cells) at 12 months (see Figure 2). Mainly because of intolerance and poor responses, a substantial number of patients crossed over from the IFN-? plus Ara-C arm to the imatinib arm, thus overall survival analysis based on an intention-to-treat basis was not assessable. The subsequent analysis of the trial confirmed the initial impressive results.10–12

In the IRIS study, routine follow-up data were collected for all randomised patients, including overall survival. For those who discontinued study treatment, quarterly assessments included whether patients were alive, deceased, lost to follow-up or had received transplant. By the median five-year cut-off (range: 5–5.5 years) after the last patient had been recruited into the study, 57 of the 553 patients (10%) initially randomised to imatinib were documented to have died. Of the remaining 496 patients, 333 (67%) had follow-up data of greater than five years, 126 (25%) had follow-up data between 4.5 and 5 years, 11 (2%) had followup data between 4 and 4.5 years and only 26 (5%) were prematurely lost to follow-up with available survival data of less than four years. Using the Kaplan-Meier method, in which available data for each patient are considered and survival is censored at the last follow-up when patients are known to be alive, the probability of overall survival at five years was 89%. Landmark analyses were performed for patients on imatinib at 12 and 18 months (n=509 and n=480, respectively) and stratified for complete cytogenic response (CCyR – Ph+ = 0%), partial cytogenetic response (PCyR – Ph+ >0–35%) or no MCyR (Ph+ >35%) at both timepoints. Progression-free survival (PFS) included all progressions to accelerated phase or blast crisis during treatment with imatinib, whereas event-free survival (EFS) also included any loss of MCyR/complete haematological response, increase in white blood count and CMLunrelated deaths on treatment as events. Overall survival (OS) considered all deaths including those after discontinuation of imatinib and irrespective of whether patients went on to transplant.

Although the level of cytogenetic response was predictive for long-term outcomes, PFS and OS were not statistically significantly different between 12-month CCyR and PCyR. Note that 64% of PCyR patients and 36% of patients without MCyR at 12 months subsequently achieved CCyR. Using the 18-month landmark, 50% of PCyR patients and 27% of patients without MCyR achieved CCyR at a later time. Long-term outcomes were evaluated based on available bcr-abl transcript levels in patients with CCyR. A 3-log reduction from standardised baseline value in untreated patients was defined as a major molecular response (MMR). No patients who achieved both CCyR and MMR at 12 or 18 months progressed to accelerated phase or blast crisis by 60 months. Approximately 5% of patients with CCyR but no MMR at 12 months (p=0.007) and only 2% of CCyR patients without MMR at 18 months (p=0.11) subsequently progressed. Of approximately 25% of CCyR patients with available PCyR analysis who did not achieve MMR at 18 months, about half did achieve MMR at a later time and their estimated EFS rate at 60 months was 91%.

Owing to the a large number of patients in the IRIS trial who crossed over from imatinib to IFN-? + Ara-C, a retrospective analysis was performed comparing outcome of patients assigned to imatinib in the IRIS trial13 with patients assigned to the IFN-? + Ara-C arm included in the French multicentre (CML 91) trial before imatinib became available.14 Inclusion criteria of both studies were similar: patients with Ph+ chronic phase CML diagnosed within six months before randomisation; hydroxyurea or anagrelide were allowed if needed. Patients who actually received the assigned study treatment were compared (n=551 for IRIS and n=325 for CML91). This comparison shows that for first-line therapy for newly diagnosed chronic-phase CML, imatinib is superior to prolonged therapy with IFN-? + Ara-C for rate of MCyR, CCyR, PFS and overall survival. Nevertheless, patients who do not have access to or who cannot tolerate imatinib can have long PFS and overall survival with IFN-? + Ara-C therapy.

Conclusion

The IRIS study was a large trial with the aim of comparing the outcome of patients who were treated with imatinib versus the standard treatment of IFN-? + Ara-C. The initial results were in favour of the imatinib arm with respect to complete cytogenetic responses and major molecular responses. The impressive results show that most of the patients included in the imatinib arm are still alive after five years of treatment. The second key finding from this trial is that over time there was no increased incidence of progression to the accelerated phase of blast crisis. In addition, the reassuring finding that side effects at six-year follow-up are the same as previously reported and no worrisome long-term side effects were observed was noted.