Lung cancer afflicts approximately 1.2 million people worldwide and results in a similar number of deaths per year.1 In the US, the number of lung-cancer-related deaths surpasses that of the next four most common cancers combined.2 Currently, almost half of all lung cancers occur inwomen, and more women die of lung cancer than breast cancer each year. Most patients present with advanced locoregional or disseminated disease and, despite advances in the multimodality treatment of nonsmall- cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), the five-year survival rate remains 10–12%. However, when patients with this type of lung cancer are diagnosed at an early stage, surgical resection has been shown to be potentially curative with overall five-year survival rates that may exceed 70%.3

Locoregional recurrences do occur after surgical therapy, yet extrathoracic dissemination tends to be the site of first recurrence and usually results in cancer-related mortality.4 Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment strategies have been employed to reduce the rate of recurrence and improve overall survival in patients with NSCLC. The results of these multimodality endeavors as well as current treatment recommendations will be highlighted in this article.

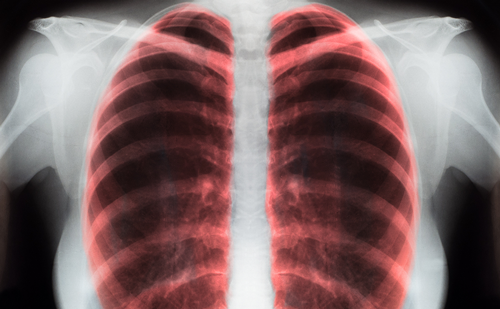

One cannot overemphasize the importance of thorough clinical staging in the evaluation of patients with NSCLC. Currently, we combine positron emission tomography (PET) with computed tomography (CT) in the preoperative evaluation of lung cancer patients. Cervical mediastinoscopy with biopsies of N2 and N3 lymph node stations is then performed in those patients with suspicious nodal disease on PET/CT, or in those with large, central pulmonary neoplasms. As will be discussed, the pathologicalconfirmation of N2 or N3 nodal metastases will influence the types and sequence of treatment modalities utilized in these patients (see Table 1).

Treatment of Stage I Non-small-cell Lung Carcinoma

For patients with clinical stage I NSCLC and no medical contraindication to operative intervention, surgical resection is regarded as the sole treatment modality of choice. This is based on retrospective analyses only, as there have not been randomized clinical trials evaluating the role of surgery versus either chemotherapy or radiation therapy alone. The optimal surgical procedure of choice has been the subject of scrutiny, yet the Lung Cancer Study Group (LCSG), in its randomized controlled trial, has proved that sublobar resection has inferior results compared with lobectomy in terms of locoregional recurrence.5 A survival difference was found in this study between the two groups in favor of the lobectomy group (p=0.08, one tailed t test). Currently, the standard of care in patients with an acceptable cardiopulmonary reserve is anatomical lobectomy for clinical stage I NSCLC.There is an ongoing clinical trial being conducted by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 140503) re-examining the role of sublobar resection in patients with early-stage NSCLC.

Five-year post-surgical survival results for stage Ia cases exceed 70%, yet significantly lower survival has been seen in patients with stage Ib disease.6 This has prompted many clinicians to investigate the use ofadjuvant therapeutic regimens to improve survival rates in patients with pathological stage Ib disease. The results from these endeavors have been conflicting. The National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) Clinical Trials Group performed a randomized adjuvant chemotherapeutic trial JBR.10 trial) in patients with completely resected stage Ib–II NSCLC. Patients with Ib disease who were randomized to adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin derived no survival advantage to chemotherapy at five years compared with those in the observation arm.7 Similar findings were also obtained in a subset analysis for stage Ib patients in the Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association (ANITA) trial.8 Here, there was no statistically significant difference in five-year survival rates (62% in the chemotherapy group versus 64% in the observational group) between the two arms.

The only randomized trial demonstrating a benefit to adjuvant chemotherapy in stage Ib patients was the CALBG trial 9633, which randomized patients with stage Ib NSCLC to receive adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel or observation.9 It was believed that the tolerable treatment strategy for this select group of patients may have led to the favorable results seen with the adjuvant chemotherapeutic regimen. This survival advantage in the adjuvant arm was not seen in the recently reported update to this study.10 A subgroup analysis suggests a benefit for those patients whose tumors are greater than 4cm. Given the lack of supportive data for the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients who have undergone complete resection of stage I NSCLC, it is our practice not to routinely recommend this therapy in our patients outside of a research protocol. Recently, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) has opened an intergroup study (E1505) to examine the role of adjuvant chemotherapy with bevacizumab, an antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor, for completely resected stages I–IIIa (for stage I tumors, size must be >4cm). There is no role for adjuvant radiotherapy in completely resected stage I NSCLC based on the findings of a large meta-analysis.11

For some patients, surgery is not an option due to poor pulmonary function, comorbid disease, or simple refusal of the invasive procedure. In lieu of surgery, these patients have received external-beam radiotherapy with modest success. Recent efforts to increase the intensity of radiation in this setting include the use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy, an example of which is stereotactic radiation. This allows for an increase in the dose delivered to the tumor while reducing the dose delivered to the normal tissues, and remains a suitable option for high-risk patients.

Treatment of Stage II Non-small-cell Lung Carcinoma

Treatment recommendations supporting the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with node-positive (N1) NSCLC are based on the findings of several randomized studies. One investigation that did notclearly demonstrate a role for adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II patients was the International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial (IALT), which randomized 1,867 patients with completely resected NSCLC to three or four cycles of a cisplatin chemotherapy doublet or observation alone. This study included patients with stage I–IIIa disease. Etoposide (57%) was the most common agent combined with cisplatin, followed by vinorelbin (27%), vinblastine (11%), and vindesine (6%). At five years, there was a 4.1% increased survival benefit seen in all patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.12 This modest gain in survival was statistically relevant, but on subset analysis was significant only for those stage IIIa patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.

Evidence of the utility of adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment ofpatients with stage II NSCLC comes from the previously mentioned NCIC JBR.10 and ANITA trials.7,8 In the NCIC JBR.10 trial, which randomized482 patients, the recurrence-free (48 to 61%) and overall survival (54 versus 69%) increases seen at five years in the adjuvant chemotherapy arm were mainly due to treatment of the stage II patients.7 Similar findings were reported in the ANITA trial, in which stage II patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy had an absolute survival benefit of13% at five years.8

Based on these studies, it is our clinical practice to refer completely resected stage II NSCLC patients for medical oncology consultationfor consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with good performance status usually receive platinum-based chemotherapy with acceptable toxicity.

Treatment of Stage III Non-small-cell Lung Carcinoma

Stage IIIa NSCLC covers a broad spectrum of patients, from those with tumors with chest wall invasion and hilar nodal metastases (T3N1) to patients with varying degrees of mediastinal lymph node involvement. This latter group can then be further examined on a spectrum beginningwith those with occult, micrometastatic N2 disease to patients with extracapsular, multistation, N2 nodal involvement. It is this tremendousheterogeneity, along with differing practice patterns among thoracic surgeons regarding completeness of mediastinal lymph node dissection, that has led to significant controversy regarding the optimal treatment of patients with stage IIIa NSCLC.

In addition to the aforementioned diversity of disease in these patients, there have been a wide variety of clinical trials conducted to ascertain optimal treatment strategies for this particular clinical dilemma. All utilize varying combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapeutic modalities. To complicate matters further, most trials are not randomized and others suffer from unreliable pre-treatment staging strategies, rendering the ability to make definitive treatment recommendations quite challenging. This lack of dependable, randomized data highlights the significance of enrolling these patients inclinical trials whenever feasible.

As discussed previously, we routinely perform cervical mediastinoscopy in patients with PET/CT evidence of hilar or mediastinal lymph node involvement or in those patients with large, central malignancies. For those patients with proven N2 disease, we employ a combined multimodal approach with curative intent. The data supporting this strategy can be gleaned from adjuvant radiotherapy trials,13 which do not demonstrate any survival advantage to slightly beneficial adjuvant chemotherapeutic studies that have been discussed.7,8,12 Neoadjuvant therapy for patients with locoregionally advanced NSCLCcarries potential theoretical advantages, including improved patient compliance, clearance of tumor from nodal stations resulting in downstaging and improved survival rates, and early micrometasticcontrol of distant disease. Retrospective reports have demonstrated significantly improved survival rates in patients whose N2 nodal disease was eradicated by pre-operative therapy.14 In this study utilizing various neoadjuvant treatment strategies, 28% of the patients had all nodal disease cleared of tumor (pN0) with a 35.8% five-year survival rate compared with an only 9% survival rate for those with residual nodal disease as determined after surgical resection.

In the 1980s, studies performed by Roth15 and Rosell16 were the first randomized efforts to employ neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage IIIa NSCLC. Both of these endeavors were closed early as significantly improved survival was noted in the interim analyses in the patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The role of induction chemoradiotherapy was initially investigated by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) for patients with stage IIIa and IIIb NSCLC.17 In this phase II trial (SWOG 8805), the investigators determined that patients with persistent nodal disease at the time of surgery had a worse survival than those whose mediastinal nodal metastases were cleared with preoperative chemoradiotherapy.

The North American Intergroup 0196 trial randomized patients to either neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery or definitive chemoradiotherapy. Both treatment arms received consolidationchemotherapy. The results of this endeavor have been published in abstract form and, although there was a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival seen in the neoadjuvantchemoradiotherapy group, overall survival was comparable between the two arms.18 The equivalent five-year survival rates between the two arms may be attributable to the particularly high mortality rate (26%) seen in patients undergoing pneumonectomy in this series.

Frequently, most patients presenting with stage IIIb NSCLC are offered definitive chemoradiotherapy for the treatment of their lung cancer, as surgical intervention offers little benefit. Although not well-studied in randomized trials specifically for stage IIIb patients, combination chemoradiotherapy has been found in a large meta-analysis to significantly increase two- and five-year survival rates compared with treatment with radiotherapy alone.19 Completed phase III trials have determined that concurrent chemoradiotherapy results in improved two- to five-year survivalrates compared with sequential chemoradiotherapy strategies.20

A limited role of surgery has been defined in the multimodality treatment of well-selected patients with stage IIIb NSCLC. Retrospective analysesfrom centers performing a high volume of complex thoracic surgery procedures report acceptable rates of peri-operative morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing pulmonary resection for T4 cancers involving the carina,21 atrium,22 and superior vena cava.23 Studies have also reported five-year survival rates after surgical resection of patients with intralobar satellite nodules (T4) comparable to survival seen inpatients with T1 and T2 NSCLC without satellite lesions.24

Treatment of Stage IV Non-small-cell Lung Carcinoma

Platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard of care in the treatment of patients with stage IV NSCLC and adequate performance status. External-beam radiotherapy and surgical intervention rarely have a role in the treatment of lung cancer in this patient population. There is a subset of patients who present with an isolated brain metastasis as the only site of metastatic disease. Based on small, retrospective series, it may be reasonable to pursue aggressive local therapy to address the primary tumor and brain lesion.

One recent study demonstrated a median survival rate of over twoyears in patients with synchronous brain lesions and node-negative NSCLC primary tumors after surgical resection of the primary andeither resection or stereotactic radiation therapy to the metastatic lesion.25 There are conflicting data regarding the value of whole-brain radiation therapy in this particular patient population, and no clear recommendations are available regarding the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in this setting. Small case series are also available, which describe long-term survival in patients undergoing surgical treatment of both adrenal metastases and their NSCLC primaries in well-selected patients.26

Summary

It is certain that, other than surgery for stage I NSCLC, no one single therapeutic modality is able to achieve a cure for most patients with NSCLC. It is our practice to include the use of adjuvant chemotherapyafter complete surgical resection of patients found to have N1-positive, stage II NSCLC. We routinely employ minimally invasive thoracoscopic techniques in the surgical treatment of NSCLC in our clinical practice at the Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomy has been demonstrated to aid in the administration of systemic chemotherapy for resected NSCLC patients compared with those who have undergone lobectomy via the traditional approach utilizing a formal thoracotomy incision.27 This is comparable to chemotherapy tolerance after thoracoscopic lobectomy in our hands.28 We postulate that patients receiving complete adjuvant treatment regimens after minimally invasive lobectomy may have improved survival compared with those who require the traditional approach. No data are available yet to confirm this supposition.

Patients who are found to have N2 nodes involved with metastatic NSCLC at the time of mediastinoscopy are offered neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy at the Mount Sinai Medical Center, followed by surgical resection in appropriate cases. For patients with normal PET/CTimaging with regard to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes, we begin our thoracoscopic pulmonary resection with an ipsilateral mediastinal lymph node dissection with frozen section pathological analysis of nodal tissue. Occasionally, unsuspected N2 disease is discovered and we will postpone thoracoscopic lobectomy until after the completion of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. These patients will undergo clinical restaging upon the completion of neoadjuvant therapy, and a cervical mediastinoscopywill also be performed to ensure eradication of N2 nodal disease before proceeding with pulmonary resection.

We have found the multidisciplinary approach to treating patients with lung cancer to be an effective method in ensuring appropriate care in these complex clinical situations. We, along with our medical and radiation oncology colleagues, are frequently evaluating lung cancer patients in concert to arrive at a unified treatment strategy.