Lung Cancer – Attributable to Active Tobacco Smoking in Women

Smoking habits vary within the different countries in Europe, with a significant decrease in tobacco consumption in the UK, Sweden and Finland between 1970 and 1994 and a significant increase in Portugal (+64.2%).5 Even if active tobacco smoking is the main cause of lung cancer in females, the attributable risk is inferior to that noted in males. Worldwide, in 2000 an estimated 85% of lung cancer cases in men and 47% in women were attributable to tobacco smoking.1 In the US, the proportion attributable to tobacco smoking in females is pretty much the same as in males. Moreover, there is now a convergence between lung cancer incidence in the youngest birth cohorts, reflecting the convergence in cigarette use in males and females.6 In Europe, about 70% of lung cancer cases in females are attributed to an active smoking habit versus 85% in males,7 whereas in Asia very few lung cancer cases in females are attributable to tobacco smoking. Even if the incidence of lung cancer in male non-smokers is consistently higher than in female non-smokers,8 the proportion of non-smokers in females with lung cancer is rather significant compared with males in all studies.9-11

Higher Tobacco-smoke Susceptibility in Females

Some case-control studies suggest a higher susceptibility to tobacco for females. A 1993 analysis found an odds ratio of 27.9 (95% confidence interval (CI) 14.9–52) for women who have smoked 40 pack-years (one pack a day for 40 years or two packs a day for 20 years, etc.) relative to lifelong non-smokers, versus 9.6 (95% CI 5.64–16.3) for males.12 Also, in an American Health Foundation case-control study, the relative risk of female smokers was estimated to be 1.5 times that of males.13 On the other hand, cohort studies demonstrated either no difference between genders regarding the risk linked to tobacco-smoke exposure or a higher risk in men.14–16 There are many differences between genders that could favour a higher susceptibility to tobacco in females. Capacity of DNA repair is inferior in females.17 DNA-adduct formation due to tobacco smoke is more frequent in females than in males, regardless of the level of smoking, and CYP1A1 (a gene involved in phase I of the metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) level of expression is higher in females.18 P53 transversion mutation (G:C T:A) is of high frequency in human lung cancer and probably the result of DNA damage induced by carcinogens of tobacco smoke. In non-tumoral lung tissue, transversion and DNA adducts were more frequent in females even though tobacco exposure was less than in males.19 Genetic polymorphisms may explain some individual variations in the risk due to smoking habits. Among the Glutathione S-transferases, the μ isoenzyme has been extensively studied. A lack of activity is associated with an increased risk in smokers.20 Deletion of the gene results in a higher increase of the risk in female smokers than in male smokers.21 Gastrin-releasing peptides (GRPs) are involved in the development of normal human lung and cell proliferation. They act through a receptor, GRP-R. The receptors are mainly in epithelial cells and fibroblasts with a high affinity for nicotine. It has been demonstrated that in non-smoking females this receptor is expressed in 55% of cases versus none in non-smoking males. In smokers of less than 25 pack-years, it is expressed in 75% of females versus 20% of males.22 Hyperexpression in females could be due to the fact that the receptor gene is in a part of the X-chromosome escaping inactivation.

Also, hormonal factors, especially oestrogens, are involved in lung cancer risk, especially for adenocarcinomas. Hormone-replacement therapy has controversial effects on the risk of developing a lung cancer, with some studies indicating an excess of risk and others showing no influence or even a protective effect.23–25 All of these studies were case-control studies and prospective studies are needed to allow for a clear conclusion. Receptors α and β to oestrogens have been demonstrated in bronchial tumour cells, with more frequent expression in females.26 Thus, oestrogens could play a role through activation of the receptors. They also act as a direct carcinogen after metabolic activation to catechol oestrogens, which can form DNA adducts but can also induce the CYP1A1 gene.26,27

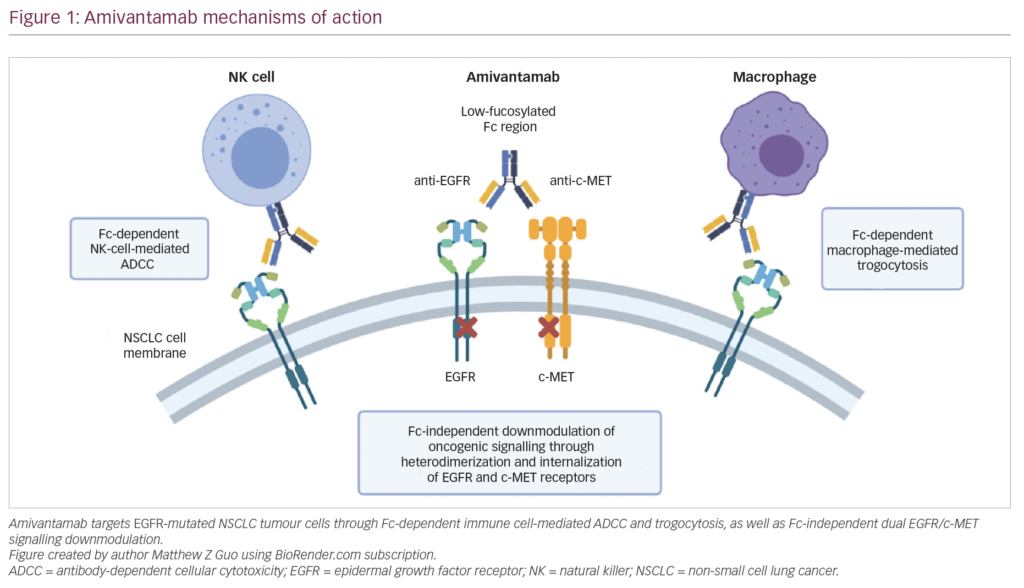

Some gender differences – genetic – are more involved in prognosis than in susceptibility. For example, K-ras mutation of codon 12 in adenocarcinoma is more frequent in female smokers with lung cancer than in males,28 but epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations of the intracellular domain gene are more frequent in females, accounting for higher response rates with inhibitors of tyrosine kinase observed in females with lung cancer (especially adenocarcinoma and in Asian people).29,30 Of interest is the fact that K-ras mutations and EGFR mutations are mutually exclusive, the former having a negative impact on survival and the latter having a positive impact.31 Although there are many biological differences between the genders regarding the susceptibility to tobacco-smoke carcinogens, there is still controversy around the potentially higher risk in females.32,33 There are several potential biases: confusion between absolute and relative risk in casecontrol studies; reluctance to report smoking for females; and the role of environmental tobacco exposure (ETS).

Other Risk Factors

Among the other risk factors, ETS has been extensively studied, with controversial results probably related to the difficulties in measuring exposure. Five meta-analyses concluded that there is an increased risk of developing lung cancer in females who are exposed to the tobacco smoke of their spouse or partner.34 More recent studies confirm the increased risk linked to ETS.35,36 A family history of lung cancer is another risk factor.37 Previous history of respiratory disease is advocated as a risk factor for lung cancer and is more frequently reported in females with lung cancer than in controls.38 Occupational risk is less frequent in females than in males and is difficult to assess in non-smokers, essentially because members of the working class who perform manual labour are rarely non-smokers. Recently published, one of the largest European case-control studies (223 cases) concluded that occupation was only a limited risk factor and more apparent in females than in males (although the lower number of the confidence interval was <1).39 The role of radon in-house is now recognised with a small added risk.40 This added risk has been estimated in Canada to represent 10% of all lung cancers.41 In developing countries, the role of fossil combustion is well established.42–44 The role of cooking fumes in Asia is also well known and was recently reconfirmed in Hong Kong in a case-control study with a dose–response relationship.44,45 Age and Histological Distribution in Males and Females

Age at diagnosis has been considered as higher in females in some studies,11,47 whereas in other studies authors report a lower age.9 These discrepancies might be due to the proportion of non-smokers in these series. Non-smokers are older at lung cancer diagnosis than smokers.48 Adenocarcinoma is the main histological subtype in females whether or not they are smokers. The second in frequency is small-cell lung cancer. Even if adenocarcinoma is increasing in frequency in males, squamous cell carcinoma is still the main histological subtype in males, at least in Europe.49,50 An increase in adenocarcinoma incidence in males might be due to the type of cigarette used: filters and blonde blend induce a deeper inhalation and thus more peripheral distribution of the smoke, which is where adenocarcinomas arise.51

The main epidemiological novelty in lung cancer is the tremendous increase of its frequency in females. This phenomenon has already been observed for several years in the US but is more recent in Europe. Even if tobacco smoking appears to be the main cause, other risks seem to be rather specific in females even if smoking habits are quite different. Genetic differences and hormonal factors underlie these epidemiological features.