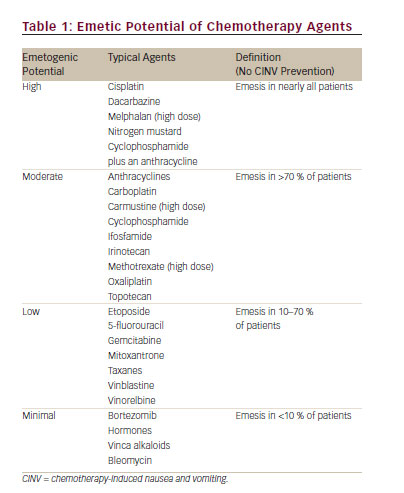

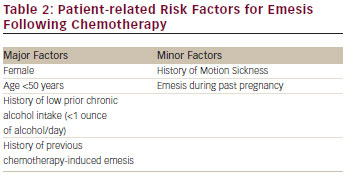

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is associated with a significant deterioration in quality of life and is perceived by patients as a major adverse effect of the treatment.1,2Increased risk of CINV is associated with the type of chemotherapy administered (see Table 1) and specific patient characteristics (see Table 2).3

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is associated with a significant deterioration in quality of life and is perceived by patients as a major adverse effect of the treatment.1,2Increased risk of CINV is associated with the type of chemotherapy administered (see Table 1) and specific patient characteristics (see Table 2).3

The use of 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists plus dexamethasone has improved CINV control.4 Recent studies have demonstrated additional improvement in CINV control with the use of three new agents: palonosetron, a second-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonist;4 aprepitant, the first agent available in the drug class of neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor antagonists;5,6 and olanzapine, an antipsychotic that blocks multiple neurotransmitters in the central nervous system.7–9

The primary endpoint used for studies evaluating various agents for the control of CINV has been complete response (no emesis, no use of rescue medication) over the acute (0–24 hours), delayed (24–120 hours) and overall (0–120 hours) post-chemotherapy periods.3 Studies have shown that the combination of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone has improved the control of emesis in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) over a 120-hour period following chemotherapy administration.3,4 The addition of aprepitant to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone has also improved the control of emesis in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) over the 120-hour post-chemotherapy period.5,6 Many of these same studies have measured nausea as a secondary endpoint and have demonstrated that nausea has not been well controlled.10

Emesis is a well-defined event that is easily measured, but nausea may be more subjective and more difficult to measure. There are, however, two well-defined measures of nausea that appear to be effective measurement tools that are reproducible: the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Likert Scale.11 The VAS is a scale from 0 to 10 or 0 to 100 with zero representing no nausea and 10 or 100 representing maximal nausea. The Likert Scale asks patients to rate nausea as none, mild, moderate or severe.

Many studies have reported the secondary endpoint of ‘no significant nausea’ or ‘only mild nausea’.3–6 Studies that have reported ‘no nausea’ may be more useful in identifying the most effective available antinausea agents. 10

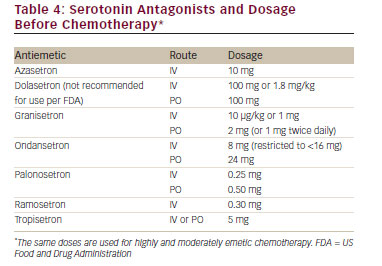

Antiemetic agents have been developed by identifying the receptors involved in emesis and nausea and creating agents that effectively block these receptors. Table 3 lists the important receptors and the receptor antagonists. Table 4 lists the serotonin antagonists and the common dosages used in clinical settings.

Despite the introduction of more effective antiemetic agents, emesis and nausea remain a significant complication of chemotherapy.

The purpose of this review is to provide information on the current recommendations for the prevention and treatment of chemotherapyinduced emesis and nausea. The recommended agents in various clinical settings will be described using the recently established guidelines from the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO),12 the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)13 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.14

Types of CINV

Five categories are used to classify CINV: acute, delayed, anticipatory, breakthrough and refractory. Nausea and vomiting may occur any time after the administration of chemotherapy, but the mechanisms appear different for CINV occurring in the first 24 hours after chemotherapy in contrast to that what occurs in the period of 1 to 5 days after chemotherapy. In order to differentiate these mechanisms, the term acute-onset CINV refers to nausea and/or vomiting occurring within 24 hours of chemotherapy administration.3 The incidence of acute emesis and/or nausea reflects several treatment-related factors, including the environment in which chemotherapy is administered, the emetogenicity of the chemotherapy, the dosage of the emetogenic agents and patient-related factors.3 Nausea and/or vomiting that develop more than 24 hours after chemotherapy administration is known as delayed emesis and/or nausea. Typically occurring with administration of cisplatin, doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide, delayed emesis/nausea is more common in those who experience acute emesis/nausea. Other predictive factors include the dose and the emetogenicity of the chemotherapeutic agent, patient gender and age and protection against nausea and vomiting in previous cycles of chemotherapy.1,3

For cisplatin, which has been most extensively studied, delayed emesis reaches peak intensity 2–3 days subsequent to chemotherapy administration and can last up to a week.1,12–14 If patients experience CINV, they may develop a conditioned response known as anticipatory nausea and/or vomiting, which occurs prior to the administration of chemotherapy in future chemotherapy cycles and is attributed to the adverse memory of prior CINV. Incidence rates for this type of nausea and vomiting range from 10–45 %, with nausea occurring more frequently.1 Vomiting and/or nausea that occurs within 5 days after prophylactic use of antiemetic agents or requires ‘rescue’ is called breakthrough emesis.3 Vomiting and/or nausea occurring after chemotherapy in subsequent chemotherapy cycles when antiemetic prophylaxis and/or rescue have failed in earlier cycles is known as refractory emesis.1,12–14

Clinical Management of CINV

Principles in the Management of CINV

Antiemetic guidelines have been published by NCCN,14 ASCO,13 and MASCC.12 These guidelines form the basis for the recommendations for the management of CINV. As new information and new studies emerge, the guidelines will evolve to provide the highest-quality evidencebased clinical practice. Single-Day Chemotherapy Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy For patients receiving HEC, current evidence suggests the following:12-14

• P re-chemotherapy – Any of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists with dexamethasone and oral aprepitant. Fosaprepitant,15,16 an intravenous equivalent to 3 days of oral aprepitant, may be administered as an alternative to oral aprepitant on day 1. The second-generation palonosetron is considered the preferred 5-HT3 receptor antagonist by the NCCN guidelines.14 All of the guidelines suggest that the combination of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin should be considered as HEC and the appropriate preventative agents should be used.

• P ost-chemotherapy – Oral aprepitant on days 2 and 3 (omit if fosaprepitant has been given on day 1) and dexamethasone on days 2 to 4. It is important to note that the oral first-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are no longer recommended for the control of delayed emesis.

Moderately Emetogenic Chemotherapy

For patients receiving MEC, current evidence suggests the following;12–14

• P re-chemotherapy – The 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron plus dexamethasone. If palonosetron is not available, ondansetron or granisetron may be employed in US Food and Drug Administrationrecommended doses.

• Post-chemotherapy – Dexamethasone on days 2 to 4.

• T wo recent studies have demonstrated that palonosetron plus dexamethasone on day 1 were equivalent to palonosetron plus dexamethasone, days 1 to 3.17,18

• Antiemetic guidelines of the past19 included the available oral firstgeneration 5-HT3 receptor antagonists as optional therapy for the prevention of delayed emesis, but the level of evidence supporting this practice is limited.20-22 The first-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are no longer recommended for use post-chemotherapy.12–14

Low Emetogenic Chemotherapy

• For patients receiving low emetogenic chemotherapy, a single agent in the form of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, or a phenothiazine, depending on the clinical situation, should be used pre-chemotherapy, and an antiemetic following chemotherapy should be given only as needed.

Treatment of Breakthrough CINV

A phenothiazine, metoclopramide, dexamethasone or olanzapine may be effective in the treatment of breakthrough nausea and vomiting.14 A 5-HT3 receptor antagonist may also be effective unless a patient presents with nausea and vomiting that developed following the use of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist as prophylaxis for chemotherapy- or radiotherapyinduced emesis. It is unlikely that breakthrough nausea and vomiting will respond to an agent in the same drug class after unsuccessful prophylaxis with an agent with the same mechanism of action. Patients who develop nausea or vomiting post-chemotherapy (days 1 to 5) despite adequate prophylaxis should be considered for treatment with a 3-day regimen of oral olanzapine or oral metoclopramide. A recently completed randomised phase III study demonstrated that oral olanzapine (10 mg/day for 3 days) was significantly better than oral metoclopramide (10 mg TID for 3 days) in controlling both emesis and nausea in patients receiving HEC who developed breakthrough CINV despite guideline-directed prophylactic antiemetics.23

It is important to note that aprepitant has been approved as an additive agent to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone for the prevention of CINV. It has not been studied and should not be used to treat breakthrough nausea and vomiting.

Refractory CINV

Patients who develop CINV during subsequent cycles of chemotherapy when antiemetic prophylaxis has not been successful in controlling CINV in earlier cycles should be considered for a change in the prophylactic antiemetic regimen. If anxiety is considered to be a major patient factor in the CINV, a benzodiazepine, such as lorazepam or aprazolam, can be added to the prophylactic regimen. If the patient is receiving HEC, olanzapine (days 1 to 4) can be substituted for aprepitant or fosaprepitant in the prophylactic antiemetic regimen.9 If the patient is receiving MEC, aprepitant or fosaprepitant can be added to the palonosetron and dexamethasone antiemetic regimen.24

Anticipatory CINV

In order to prevent the occurrence of anticipatory CINV, patients should be counselled prior to the initial course of treatment concerning their ‘expectations’ of CINV. Patients should be informed that effective prophylactic antiemetic regimens will be used and that 70–75 % of patients will have a complete response. The most effective prophylactic antiemetic regimen for the patient’s specific type of chemotherapy should be used prior to the first course of chemotherapy in order to obtain the optimum control of CINV during the first course of chemotherapy. If CINV is effectively controlled during the first cycle, it is likely that the patient will have effective control during subsequent cycles of the same chemotherapy. If the patient has a poor experience with CINV in the first cycle, it may be more difficult to control CINV in subsequent cycles, and refractory and/or anticipatory CINV may occur.

The use of anti-anxiety medications such as lorazepam or another benzodiazepine may be considered for excess anxiety prior to the first course of chemotherapy in order to obtain an optimum outcome and prevent anticipatory CINV. If anticipatory CINV occurs despite the use of prophylactic antiemetics, behavioural therapy might be considered.

Multi-day Chemotherapy and High-dose Chemotherapy with Stem Cell or Bone Marrow Transplantation

Although there have been significant improvements in the prevention of CINV in patients receiving single-day HEC and MEC, there has been limited progress in the prevention of CINV in patients receiving multiday or high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell transplant. The current recommendation is to give a first-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone daily during each day of chemotherapy in patients receiving multi-day or high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell transplant.25 This regimen appears to be at least partially effective in controlling acute CINV, but is not effective in controlling delayed CINV. The complete response in most studies of 5 days of cisplatin and in

various high-dose chemotherapy regimens is 30–70 % with the majority of studies reporting a complete response of <50 %.25

Patients should receive the appropriate prophylaxis for the emetogenic risk of the chemotherapy for each day of the chemotherapy treatment. Both acute and delayed CINV may occur on day 2 or subsequent chemotherapy days and delayed CINV may occur after the last day of the multi-day chemotherapy treatment.

The antiemetic agents palonosetron, aprepitant and olanzapine have shown effectiveness in controlling both acute and delayed CINV in patients receiving single-day MEC and HEC. They may have application in patients receiving multi-day or high-dose chemotherapy. Palonosetron has been used in one report of patients receiving 5 days of cisplatin,26 and Albany et al.27 reported that the addition of aprepitant to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone significantly improved the complete response in patients receiving 5 days of cisplatin.

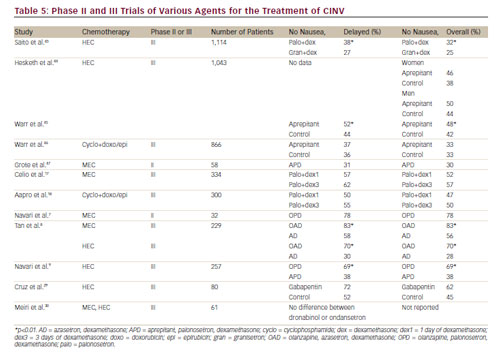

Prevention and Treatment of Nausea

The current data in the literature from multiple large studies suggest that the first- or second-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and aprepitant have not been effective in the control of nausea in patients receiving either MEC or HEC, despite the marked improvement in the control of emesis with these agents.10 Table 5 summarises major phase II and phase III clinical trials involving the first- and second-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, dexamethasone, aprepitant, olanzapine and gabapentin. It appears that neither the serotonin 5-HT3 nor the substance P receptors may be important in mediating nausea. Recent phase II and phase III studies with olanzapine have demonstrated good control of both nausea and emesis in patients receiving either MEC or HEC7–9 suggesting that the serotonin 5-HT2c and/or the dopamine receptors may be important mediators of nausea. Preliminary small studies with gabapentin,28,29 cannabinoids,30,31 and ginger32–34 are inconclusive in defining their role, if any, in the prevention of CINV. At this time, olanzapine appears to have high potential for the prevention of both emesis and nausea in patients receiving MEC or HEC.8,9 If patients are having difficulty with significant nausea, consideration should be given to including olanzapine in their prophylactic antiemetic regimen.8,9 Olanzapine may also be efficacious in the treatment of breakthrough nausea and emesis.23

Conclusions and Future Directions

The first-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (dolasetron, granisetron, ondansetron, tropisetron, ramosetron and azasetron) have significant and similar efficacy in the prevention of acute CINV for patients receiving MEC and HEC. However, these agents do not appear to have significant efficacy in the prevention of delayed CINV,21,22 and these 5-HT3 agents compete primarily on an economic basis. The second-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron improves the complete response rate of acute and delayed emesis in patients receiving MEC and HEC. The current data in the literature of multiple large studies suggest that neither the first- or secondgeneration 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have been effective in the control of nausea in patients receiving either MEC or HEC, despite the marked improvement in the control of emesis.

The neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant significantly improves the control of acute and delayed CINV when added to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone for patients receiving HEC. The appropriate use of aprepitant in patients receiving MEC will be determined by future studies. Aprepitant does not appear to be effective as an antinausea agent. Rolapitant35 and netupitant36 are NK-1 receptor antagonists currently in phase III trials, and they appear to have potential for use in the prevention of CINV.

Recently completed phase II and phase III clinical trials have demonstrated that the use of olanzapine in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone is safe and effective in the prevention of emesis and nausea in patients receiving MEC and HEC.7–9 Olanzapine may be an important agent in the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea.9,10 Olanzapine is known to affect a wide variety of receptors including dopamine D2, 5-HT2C,histaminic and muscarinic receptors.37-39 Any or all of these receptors may be the mediators of chemotherapyinduced nausea. Olanzapine also appears to be an effective agent in the treatment of breakthrough emesis and nausea.23

Preliminary small studies with gabapentin have shown some effectiveness in the control of chemotherapy-induced emesis, but the nausea control remains to be determined. The studies on the use of cannabinoids and ginger do not support the use of these agents as effective in CINV prevention. Clinicians and other healthcare professionals involved in administering chemotherapy should be aware that studies have strongly suggested that patients experience more acute and delayed CINV than is perceived by practitioners,40 and patients often do not receive adequate prophylaxis.41,42 A number of international organisations have published extensive guidelines on the use of prophylactic antiemetic regimens and directives on the management of patients with breakthrough, refractory and anticipatory CINV.12–14 Oncology practitioners are encouraged to use evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of CINV.

Palonosetron, aprepitant and olanzapine have not been extensively studied in multi-day chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation or radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Future studies may address whether these agents would be effective in patients who experience nausea and vomiting during these clinical settings, and may determine not only how these agents should be used and what combinations of new and older agents will be the most beneficial for patients, but may also provide new information on the mechanism of CINV.