Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic, Gram-negative, spiral-shaped, flagellated bacterium that colonises the mucous layer of the human stomach.1 It has been causally linked with a diverse spectrum of gastrointestinal disorders, including gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastric adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma.2 Several investigators have studied whether H. pylori causes non-digestive diseases, but these associations, if any, are uncertain.3

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic, Gram-negative, spiral-shaped, flagellated bacterium that colonises the mucous layer of the human stomach.1 It has been causally linked with a diverse spectrum of gastrointestinal disorders, including gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastric adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma.2 Several investigators have studied whether H. pylori causes non-digestive diseases, but these associations, if any, are uncertain.3

The relationship between H. pylori infection and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) has been investigated since 1998, when an Italian group reported a significant increase of the platelet count in eight of the 11 ITP patients in whom the bacterium was eradicated.4 However, subsequent reports have produced inconsistent results. Most of these studies involved a relatively small number of patients, the median observation following eradication was often less than one year and the effects of prior therapies were unclear. In addition, studies usually included patients with mild thrombocytopenia who would not ordinarily have been treated. Therefore, the effects of H. pylori eradication in the management of patients with ITP have remained undetermined. The aim of this article is to summarise the current evidence linking H. pylori infection to ITP, and to provide practical guidelines for H. pylori infection detection and management.

Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori Infection

The seroprevalence of H. pylori infection in otherwise healthy individuals varies greatly between countries and increases with age.2 Adults from developing countries show a prevalence approaching 80%, whereas rates of <60% are seen in developed countries. This rate is lower (<10%) in children below 10 years of age. In an adult cohort from the US, positive H. pylori serology ranged from 17% for persons aged between 20 and 29 years to 57% for individuals aged ≥70 years.5 Within the US a higher frequency of infection has been demonstrated in non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican-Americans.5,6

Table 1 reports the prevalence of H. pylori infection in adults with ITP from 21 case series (studies including at least 15 cases) identified in a PUBMED search. The method of detection in these studies was the 13-carbon (C) urea breath test. Most studies were conducted in Italy or Japan, where the H. pylori rate in the middle-aged adult general population is around 70%.7,8 A low prevalence of H. pylori infection was found in 74 North American patients.9 This was not dissimilar from that observed in a healthy American Caucasian population.6 Using serological tests, Michel et al. recorded a low prevalence (29%) of H. pylori infection in 51 adult ITP patients of French Caucasian origin; the same rate of infection was found in control subjects.10 These findings suggest that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in adult ITP patients may not differ from that of the general healthy population when matched for age and geographical area.

The prevalence of H. pylori in children with ITP also varies widely among different populations. H. pylori infection was not detected in any of 17 paediatric patients with ITP in a Finnish population.11 In contrast, 11 of 35 (31%) Turkish children were shown to have an H. pylori infection as documented by a positive 13C urea breath test.12 A study from Japan reported the presence of H. pylori infection in two of 10 children.13 H. pylori infection was detected in nine of 22 children (41%) from northern Taiwan.14

Mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori-induced Thrombocytopenia

Although clinical studies suggest the involvement of H. pylori, little is known about the pathogenesis of H. pylori-associated ITP. Many hypotheses have been advanced during the last few years about the mechanisms by which H. pylori may cause ITP. One of them is molecular mimicry, according to which H. pylori could induce antibody production in response to antigens that cross-react against various platelet glycoprotein antigens.

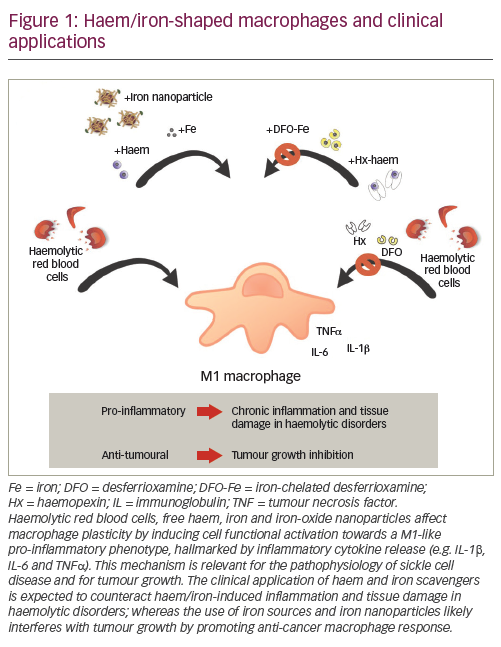

The possible role of cytotoxin-associated antigen A (CagA)-positive strains as a pathogenic candidate for ITP was recognised in two recent molecular studies. The first showed a decline in platelet-associated immunoglobulin G in ITP patients after the eradication of H. pylori infection, as well as the existence of a molecular mimicry between those antibodies and the CagA protein.15 The second study demonstrated that CagA antibodies cross-react with a peptide specifically expressed by platelets of patients with ITP.16 This study, as well as supporting an association between CagA and ITP, also proposed a possible explanation for the fact that ITP may occur in only a small subset of patients infected by CagA-positive strains. In this regard, it should be noted that most Japanese H. pylori strains are positive for CagA17 and have the intact Cag pathogenicity island (CPI).18

Recently, Semple et al. demonstrated that in the presence of antiplatelet antibodies, the lipopolysaccharide of Gram-negative bacteria can significantly enhance Fc-dependent platelet phagocytosis.19 These results suggest that infectious agents in combination with antiplatelet antibodies could affect platelet destruction in vivo, which may be at least one explanation of why thrombocytopenia worsens in some patients with ITP during infections and resolves in other patients with ITP treated with bacterial eradication therapy.

Clinical Manifestations

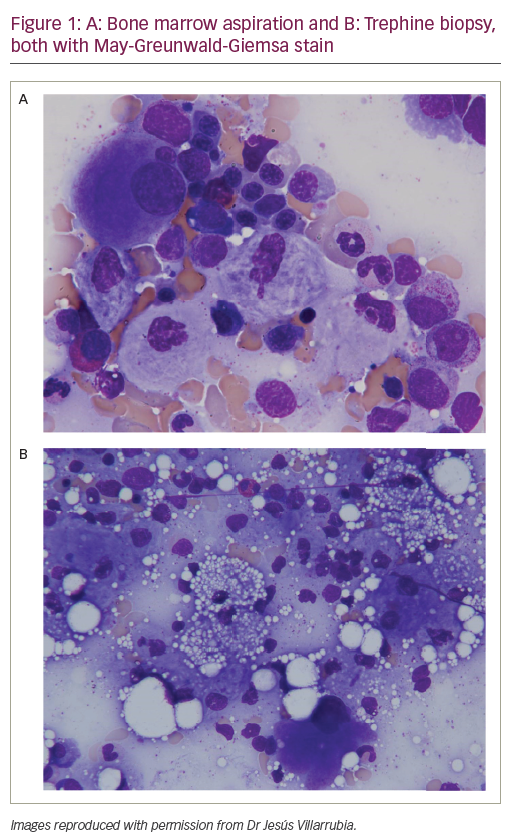

All prospective series that we reviewed reported no significant differences in the clinical presentations of ITP, aside from older age, in H. pylori-positive cases (see Table 1). A significant association between H. pylori infection and the presence of symptoms of dyspepsia has been reported by Michel et al.,9 but not by Stasi et al.20 A cross-sectional study by Fukui et al. did not find any correlation between H. pylori infection and thrombocytopenia during pregnancy.21 In a retrospective Japanese study, the H. pylori-positive positive group was significantly older (p<0.005) and had more cases of hyperplastic megakaryocytes in the bone marrow (p=0.01) than patients without H. pylori infection.22

Response to Eradication Therapy

The eradication therapy used in all studies included a proton pump inhibitor, clarythromycin and amoxicillin given for one week (‘triple therapy’). The platelet response to such therapy is summarised in Table 2. In the phase III trial, Suzuki et al. evaluated the platelet count in a group of 25 H. pylori-positive chronic ITP patients who were randomised to receive treatment or no treatment for H. pylori infection.23 Response to the treatment was defined as complete (CR) if the platelet count was above 150×109/l and partial (PR) if the platelet count increased by more than 50×109/l six months after the eradication therapy. The investigators found that the eradication of H. pylori infection in patients with ITP was associated with a platelet response of 46.2% in the eradication group (4 CR and 2 PR) and 0% in the non-eradication group (p<0.01). The platelet response was also significantly more common in patients with infection sustained by CagA-positive strains of H. pylori (p=0.04).

The overall response of the 17 phase II trials was 58%, ranging from 0% in the American series9 to 100% in the early Italian series.4 Two of these trials had an internal control. In the Italian–English study, eradication therapy was administered to H. pylori-positive patients who either had a platelet count <50x109/l or had symptoms of dyspepsia.20 Platelet responses were observed in 17/52 patients (33%)who received treatment and 0/12 patients (0%) who did not. Inaba et al. administered one week of triple therapy to 35 patients with chronic ITP.24 A platelet response was observed in 11 of the 25 patients (44%) cured of H. pylori infection and in none of the 10 H. pylori-negative patients (p=0.015). In the retrospective study by Fujimara et al., the platelet count response was observed in 63% of the successful eradication group.22 Collectively, none of the ITP patients who were not eradicated of their H. pylori infection after triple therapy achieved a platelet response. Adverse events from eradication therapy have been described as mild, usually consisting of abdominal pain and diarrhoea, and lead to discontinuation of treatment in fewer than 5% of cases.

Conclusions

The data so far reported indicate that the prevalence of H. pylori infection in ITP mirrors the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the general population. Although the pathogenesis of ITP associated with H. pylori is still not well defined, recent evidence suggests a plausible pathogenetic mechanism involving cross-reactivity between platelet-associated immunoglobulins and the H. pylori CagA protein. The data indicate that eradication of H. pylori is accompanied by a platelet response in approximately half of ITP adult patients, with ample variations in the response rate among the various series. The chances of response appear high in the Italian and Japanese series and poor in the series from other countries. Bacterial factors (i.e. the variability of H. pylori strains) may account for these findings. Eradication therapy has a favourable toxicity profile compared with standard ITP therapy.

Should patients with ITP be routinely screened for H. pylori? Considering the low costs, non-invasiveness of diagnostic methods and the favourable toxicity profile of eradication therapy compared with standard ITP therapy, the detection and eradication of H. pylori infection should be considered in those populations with a high prevalence of H. pylori infection.

What diagnostic tests for H. pylori infection are preferable? Serological tests are very sensitive but not specific indicators of an active infection and are not useful for monitoring H. pylori eradication. Very sensitive, non-invasive diagnostic methods include the antigen stool test and the 13C urea breath test.1 The 13C urea breath test has been recommended as a clinical gold standard against which other diagnostic methods can be validated. A comparison of antibodies to H. pylori-associated antigens in platelet eluates from ITP patients in countries with different rates of H. pylori and different responses to eradication therapy is one possible area of research. The diagnosis and treatment of H. pylori infection in all patients with newly diagnosed ITP before autonomous B-cell clones have developed is another. ■