Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription inhibition

A major breakthrough in understanding the molecular drivers of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) came in 2005, with the discovery of the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F driver mutation.1 Mutated JAK activates a number of downstream pathways implicated in the proliferation and survival of malignant cells, including the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs). The pervasive activation of the JAK-STAT pathway in myelofibrosis (MF) lent credence to the development JAK inhibitors. Two multicenter phase III clinical trials led to the approval of ruxolitinib, a first-in-class JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, initially in MF,2,3 and more recently as second-line therapy in hydroxyurea (HU)-resistant/intolerant polycythemia vera (PV).4 In MF, ruxolitinib has been shown to reduce spleen size, constitutional symptoms burden, induce hematologic (especially anemia) improvements, reduce bone marrow fibrosis and JAK2 allele burden in a subset of patients, and significantly improve five-year survival.

Janus kinase inhibitors

A number of novel JAK-inhibitors have entered clinical trials for patients with MF.5 Pacritinib, an oral dual JAK2 and FMS like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitor has shown efficacy in reducing the spleen size and symptom burden in patients with intermediate- and high-risk MF6–8 with only marginal worsening of anemia and thrombocytopenia, indicating that this agent could be administered in patients with MF with low platelets at baseline, which is an area of unmet need. Unfortunately, the pacritinib phase III study in MF was placed on hold by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) effective February 2016, after an interim analysis showed increased mortality secondary to cardiac events and intracranial bleeding.

Besides pacritinib, the clinical development of a number of other JAK2 inhibitors has been prematurely halted due to drug-emergent toxicities. These included peripheral neuropathy (seen with XL019),9 Wernicke’s encephalopathy (with fedratinib),10 and various toxicities recorded with lestaurtinib.11

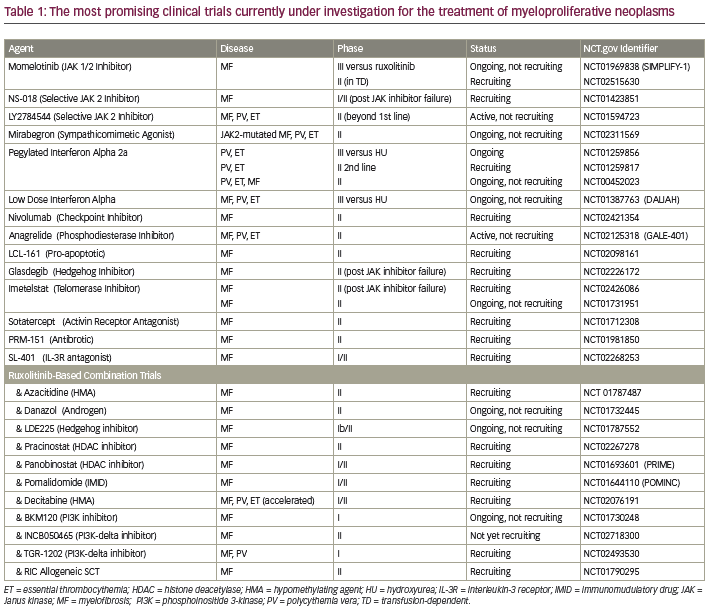

Momelotinib remains the only other JAK inhibitor undergoing evaluation in a phase III trial for patients with MF in the United States. In early phase trials, momelotinib showed significant clinical improvements in anemia, splenomegaly, and constitutional symptoms.12 The primary toxicity associated with this agent was peripheral neuropathy. Momelotinib is currently being compared to ruxolitinib in a phase III trial evaluating frontline therapy in patients with International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) scores of intermediate-1 (Int-1) or -2 or high-risk MF who require therapy (NCT01969838). Other selective JAK2 inhibitors currently under evaluation in phase I/II trials in MF include NS018 and LY27A45445 (see Table 1).

Beyond Janus kinaseinhibition—combination treatments and various pathways

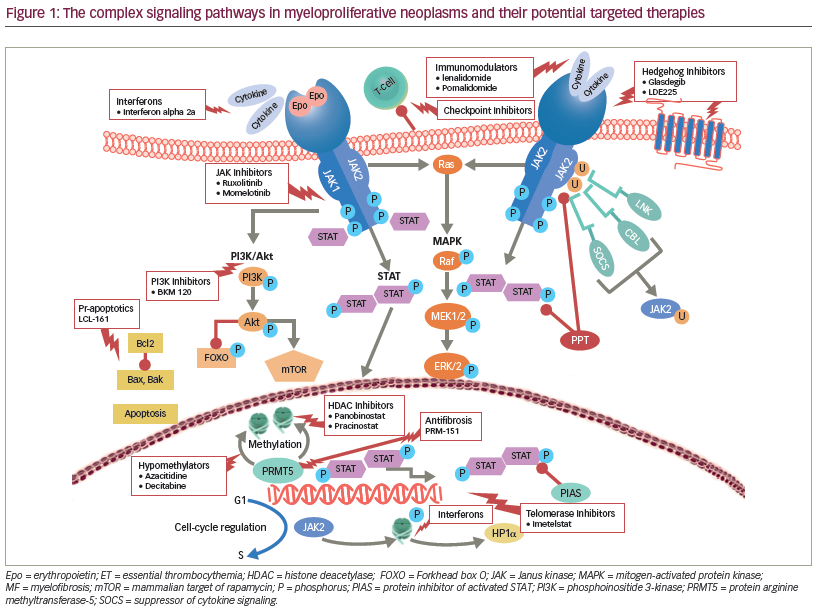

MPNs involve the constitutive activation of JAK-STAT signaling axis and its downstream effectors, including other JAK members, STAT3/5, mitogenactivated protein kinases (MAPK), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (see Figure 1) that promote cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and drug resistance in patients with MF.13–15 Independent parallel signaling pathways, including hedgehog16 and histone deacetylase (HDAC)17 interfere with cellular differentiation, hematopoiesis, and cell cycle regulation in MF. Furthermore, therapy-related worsening of blood counts may restrict the ability to administer ruxolitinib or other JAK-inhibitors in a subset of highrisk MF patients. Alternate therapeutic approaches including development of rational combinations with JAK-inhibitors as well as identification and targeting of non JAK-STAT drivers of MF may improve responses and overcome these therapeutic hurdles. The most promising agents currently being evaluated in combination with ruxolitinib include azacitidine18 (improved 24-week and overall spleen reduction rate and higher International Working Group [IWG] clinical improvement response rate as compared to historical experience with ruxolitinib alone), ,panobinostat19 (reduction in marrow fibrosis and molecular responses including JAK2 and calreticulin gene [CALR] driver mutations, isocitrate dehydrogenase [IDH] 1/2 and additional sex combs like 1 [ASXL1]), danazol20 (improved cytopenias), PI3K inhibitors15 (reversal of marrow fibrosis), hedgehog inhibitors21 (marked reduction in marrow fibrosis), and pegylated interferon (IFN) alfa-2a22 (overcoming acquired resistance to IFN monotherapy).

Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) lenalidomide and pomalidomide23,24 improve anemia and thrombocytopenia in patients with MF. In phase I/II trials, the combination of ruxolitinib and pomalidomide25 showed a response rate of 12% with anemia and neuropathy being the major toxicities. Similarly, ruxolitinib in combination with lenalidomide26 was associated with a slightly higher CI spleen response but prohibitive myelosuppression lead to early termination in a majority of patients. We believe that to improve the tolerability a sequential rather than concomitant approach should be considered when contemplating combinations with ruxolitinib. We are currently exploring such a sequential

approach in ongoing ruxolitinib combination strategies (NCT01787487, NCT02267278) (see Table 1).

Reversal or control of marrow fibrosis is an intuitive target for drug development in MF. The pure antifibrotic pentraxin27 demonstrated improvement in splenomegaly, cytopenia’s, and symptoms in a phase I/II trial in 27 patients. The overall response rate was 85%. Pentraxin is currently under study in combination with ruxolitinib in patients with MF who have intermediate- and high-risk disease (NCT01981850). Additionally, the telomerase inhibitor Imetelstat28 demonstrated a 21% IWG and 35% spleen response in phase I trial including 4 patients with complete responses and 3 with transfusion-independence. The main toxicities were transaminitis and myelosuppression. This agent is being investigated in a phase II trial (NCT02426086).

The improved hematologic and molecular responses with pegylated IFN alfa-2a,29 have resulted in the initiation of two randomized phase III trials comparing HU to pegylated IFN-2a (NCT01259856) and the monopegylated IFN-2b in the frontline setting (PROUD-PV trial; NCT01949805). These trials will help define the ideal position of IFN therapy in patients with MPNs.

Finally, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is the only potentially curative modality and should be considered in a selected subset of MF patients.30 The use of ruxolitinib prior to allo-HSCT favorably improves splenomegaly, symptoms, and performance status. A number of clinical trials are investigating this approach,31,32 with preliminary reports showing improved post-transplant outcomes.

In aggregate, ruxolitinib remains the sole JAK inhibitor currently approved for MPNs and available for commercial clinical use. The identification of the aforementioned signaling pathways and their association with the JAK/STAT axis has led to the development of rational combinations in MF. A better understanding of molecular profiles and a large number of ongoing exciting trials, suggests that the future of MPN therapy is bright.