Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 10% of haematological malignancies.1,2 Its frequency is constantly increasing with the age of the general population. Currently, <40% of myeloma patients are <65 years of age, while the incidence of elderly MM patients (>65 years of age) will increase in the near future, in part due to the increased lifespan of the population and also because of the progress made in the field of myeloma treatments.

Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 10% of haematological malignancies.1,2 Its frequency is constantly increasing with the age of the general population. Currently, <40% of myeloma patients are <65 years of age, while the incidence of elderly MM patients (>65 years of age) will increase in the near future, in part due to the increased lifespan of the population and also because of the progress made in the field of myeloma treatments.

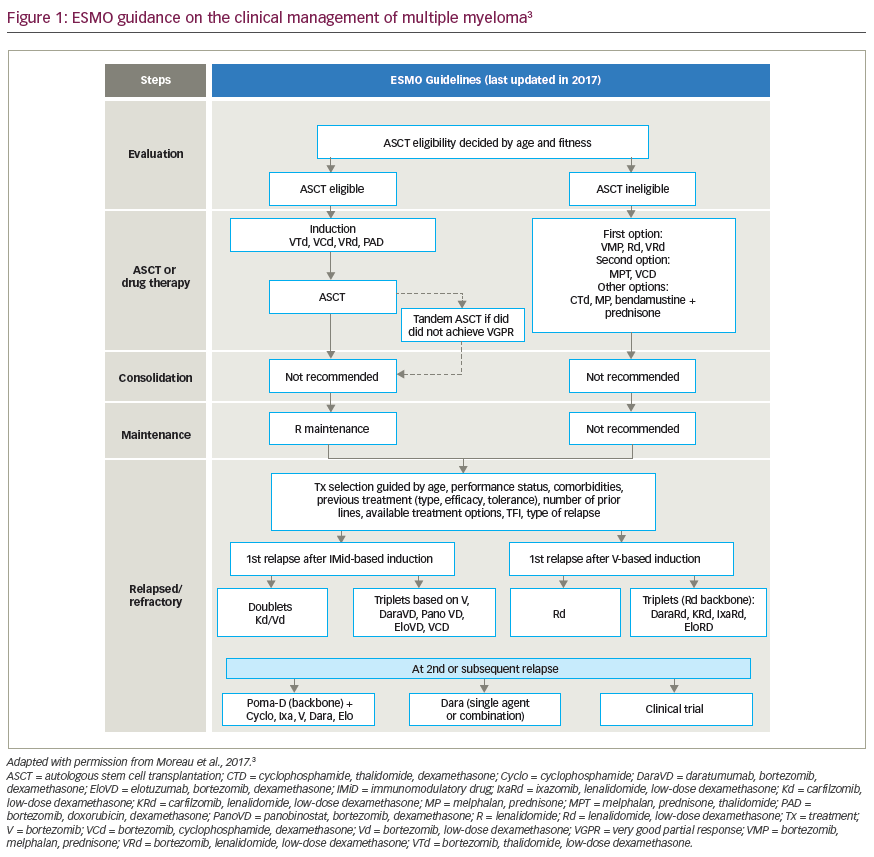

In newly diagnosed young MM patients (<65 years of age), the standard treatment is autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). For elderly (>65 years of age) or unfit patients, conventional chemotherapy (CC) is the best choice. The adverse prognostic effects of age in myeloma predominantly relate to co-morbidity, performance status, lowered physiological reserve, social support and undertreatment of the tumour. Novel, more effective treatment approaches are now available to improve outcome and extend survival.

Recently, agents with a specific and innovative mechanism of action, such as the immunomodulant drugs (IMiDs) thalidomide and lenalidomide, and bortezomib, the first proteasome inhibitor, have been shown to be safe and effective in both newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory settings.

Thalidomide and lenalidomide inhibit angiogenesis, stimulate T and natural killer (NK) cells and interfere with cytokines that play a role in the growth and the acquisition of chemoresistance of MM cells.3 Bortezomib is the first in the class of proteasome inhibitors and inhibits the 26S proteasome subunit that is responsible for transcription and degradation of the protein involved in cell proliferation and metabolism.4

Until the 2000s, the association of melphalan and prednisone (MP) represented the gold standard treatment for patients >65 years of age or not eligible for ASCT.5 Another option was a high dose of glucocorticoids alone or in combination with other agents, such as alkylators.6 In the last 10 years, the association of the new agents with these older drugs has been shown to increase response rates (RR), in particular the complete remission (CR) rate, and to improve outcomes.

In this article, we will focus on the most recent treatments for elderly myeloma patients, with particular attention paid to the balance between efficacy and safety.

Dexamethasone-based Combinations

Steroids play an important role in the treatment of both relapsed/ refractory and newly diagnosed MM.6 Dexamethasone is a simple, effective and safe primary treatment, and in the past represented one of the best choices for initial treatment.

In elderly MM patients, the use of high-dose dexamethasone is associated with a high RR, but it induces important adverse events such as infections and gastrointestinal, diabetic and psychiatric complications, which compromise the long-term outcome. Various studies have assessed the association of dexamethasone-based regimens with the new drugs for the treatment of new MM patients who are not suitable for ASCT.

Thalidomide and Dexamethasone-based Regimen

Recently, two randomised clinical trials have compared thalidomide and dexametasone (TD) with dexamethasone alone7,8 in newly diagnosed MM patients ineligible for high-dose therapy (see Table 1).

The RR was high, about 65%, including a high CR/very good partial remission (VGPR) rate (4–8% according to the studies). One of these studies also showed better long-term outcome in the TD arm, with time to progression (TTP) and progression-free survival (PFS) of 22.6 and 14.9 months, respectively, versus 6.5 months for both in the dexamethasone-only arm.8

The TD regimen has also been compared with MP,9 showing a non-statistically significant longer PFS (20.7 versus 16.7 months, respectively) but a shorter overall survival (OS) (41.5 versus 49.4 months, respectively) and shorter post-relapse survival (three versus 6.7 months, respectively).

TD-related toxicity is generally high: deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), peripheral neuropathy (PN) and infection are the most frequent adverse events. Moreover, in patients ≥75 years of age a high early-death rate and a high discontinuation of therapy was also observed.9 In patients ineligible for ASCT, TD is an effective regimen, but its toxicity is very high and may explain the high incidence of adverse events, discontinuation of therapy and early death, which may influence long-term outcomes.

The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Myeloma IX study added cyclophosphamide to TD combination (CTD) and compared it with the conventional induction regimen MP in elderly newly diagnosed MM patients.10 The ORR and CR rates were higher (see Table 1), but more time is needed to evaluate the PFS and OS.

Offidani and co-workers presented the results of a phase II study in which pegylated liposomal doxorubicin was added to TD (ThaDD) for the treatment of newly diagnosed and relapsed elderly MM patients11,12 (see Table 1).

Patients presenting at least a minor response after six courses of ThaDD were randomised to receive interferon-α plus dexamethasone (ID) or thalidomide plus dexamethasone (TD) until recurrence of disease or intolerable toxicity. After six cycles of therapy, the overall response rates (ORRs) included 30% of patients who achieved a CR, with a slight improvement of the response with maintenance in both arms.

After a median follow-up of 30 months, the two-year OS probability was significantly better in the maintenance TD arm than in the ID arm (84 versus 68%, respectively). Haematological toxicities related to induction regimen were seen in 42% of patients, including 12% grade 3–4. Severe side effects related to thalidomide were DVT (14%), fatigue (6%), constipation (4%) and tremors (4%). This regimen was shown to be effective for the treatment of elderly patients with newly diagnosed MM. The toxicity was manageable in older fragile patients as well, and complications such as infection and DVT may be prevented with adequate antibiotic and antithrombotic prophylaxis.

Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone-based Regimen

The association of lenalidomide with steroids (RD) has been approved in the US and Europe as treatment for relapsed/refractory myeloma.

In a newly diagnosed setting, a phase II trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of RD as initial therapy for MM (see Table 1).13 Thirty-four patients were enrolled and were treated with an oral daily dose of lenalidomide (25mg on days one to 21 of each 28-day cycle) and dexamethasone (40mg/day on days one to four, nine to 12 and 17 to 20). In order to prevent thrombosis, patients also received once-daily aspirin (81 or 325mg at the discretion of the physician). The combination was found to be highly effective, and among patients who did not receive high-dose therapy, the CR or VGPR rate was 67%, including 24% CR. Two-year PFS and three-year OS were 59 and 85%, respectively. Half of the patients had grade 3 or greater non-haematological toxicities (mostly fatigue). Myelosuppression was minimal.

Another phase III study compared RD with dexamethasone alone in 198 newly diagnosed patients.14 The combination therapy was superior in terms of RR (85.3 versus 51.3%, respectively) and one-year PFS (77 versus 55%, respectively). The toxicity was higher in the RD arm, especially in terms of neutropenia, infection and DVT (see Table 1).

In an attempt to evaluate the balance between safety and efficacy with different treatment schedules, a randomised phase III study compared lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethsone (Rd) versus lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone (RD).15 The OS was significantly superior with Rd than with RD (96.5 versus 86%, respectively). As expected, in the arm with high-dose dexamethsone there was an higher incidence of grade ≥3 thromboembolism (22 versus 6%), infection/pneumonia (15.7 versus 7.5%) and hyperglycaemia (9.7 versus 6.6%) (see Table 1).

Low-dose dexamethasone and lenalidomide was also combined with clarithromycine, an antibiotic that seems to optimise the effect of steroids and that appears to have immunomodulant properties, especially the suppression of interleukin (IL)-6, interacting with IMiDs such as lenalidomide.16–18 Seventy-two patients have been enrolled (see Table 1).

Autologous transplantation was allowed for eligible patients. The responses were higher and rapid, with 70% of patients achieving at least 50% paraprotein reduction after the first cycle. Among the 52 patients who did not receive ASCT, 37% achieved a CR and 33% a VGPR. At the moment of analysis, the two-year EFS was 97.2%. The most common grade 3 or higher haematological adverse events were neutropenia (19.4%), anaemia (13.8%) and thrombocytopenia (22.2%). Among the more frequent non-haematological grade 3 or higher adverse events were myopathy (11.1%) and thrombosis (9.7%); the latter occurred mainly in the context of aspirin interruption.

In a phase II trial, cyclophosphamide was added to lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (RCd) for the treatment of newly diagnosed MM patients, both eligible and not for ASCT.19 The ORR was 83%, including CR 2%, VGPR 38% and PR 43%. Grade 3–4 toxicity was mainly haematological, while the non-haematological toxicities were lower-grade and included neuropathy, diarrhoea, cystitis and thrombosis. The RCd combination showed excellent activity in the setting of new myeloma patients. No data on long-term outcome are available (see Table 1).

Bortezomib and Dexamethasone-based Regimen

The association of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib with dexamethasone proved to be an effective and safe regimen when used for induction before stem cell transplantation.20–22 A phase II trial conducted by Jagannath and colleagues evaluated bortezomib alone and in combination with dexamethasone as front-line therapy, both in eligible and ineligible for ASCT myeloma patients.23

Forty-eight patients were enrolled and received bortezomib 1.3mg/m2 on days one, four, eight and 11 for a maximum of six three-week cycles. Patients who did not reach PR after two cycles or CR after four cycles received 40mg of oral dexamethasone the day of and the day after bortezomib administration. Transplantation was not protocol-specified. Overall, the RR was 90% with a ≥VGPR rate of 42%, which included 19% of patients in CR/nCR. Response to bortezomib was rapid, with 24 patients achieving PR or better after two cycles.

After a median follow-up of 49 months, for patients who did not receive ASCT, median PFS was 21 months and the median OS was not reached. A landmark analysis, based on whether or not the patient received ASCT within six months after study discontinuation, showed no difference in the one-year survival rate between patients who received HDT and those who did not, probably because the study was not designed to reveal this difference and due to the small number of patients.

Toxicity was moderate, with few cases of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and PN. Otherwise, the trial showed significant efficacy for the bortezomib and dexamethasone combination, even in patients who did not receive high-dose therapy. There was a low adverse event rate and, interestingly, no DVTs were observed, even if patients did not receive any thromboprophylaxis.

Melphalan–Prednisone-based Combinations

Since the 1960s, MP has been considered the standard of treatment for elderly or unfit patients who are ineligible for ASCT. MP induces a 50–60% RR, with a low complete remission rate (about 5%) and a median OS of no more than two to three years.5

The introduction of novel drugs, with the demonstration of their activity as single agents, led to a combination of thalidomide, lenalidomide and bortezomib and MP in order to improve responses to and the long-term outcome of this combination.

Thalidomide, Melphalan and Prednisone

Five studies show the efficacy and safety of the association of thalidomide with MP (MPT) as the initial treatment for elderly patients or those ineligible for high-dose therapy (see Table 2).

Almost all of the studies showed an increased RR (including a higher CR rate) and a prolonged EFS/PFS, but not all of the trials were able to demonstrate an increased OS. A comparison between the studies is difficult because of variable patient selection, different schedules and the presence or not of maintenance.

In the Italian Group for Adult Haematological Diseases (GIMEMA) study, after a median follow-up of 38.1 months, the RR, including CR rate and the median PFS, was higher in the MPT group versus MP, while the median OS was almost identical: 45 and 47.6 months, respectively.24,25 Possible explanations may be that a substantial number of patients cross over from MP to thalidomide- or bortezomib-based salvage regimens after relapse or progression, and that survival from progression or relapse was significantly improved in patients who received MP at diagnosis and new agents as second-line therapy.

The MPT patients seem to be more drug-resistant, and a higher rate of failure with salvage therapy and shorter survival after relapse can partly explain the similar OS rate in the two groups. In the French Francophone Myeloma Intergroup (IFM) 99-0626 and IFM 01-0127 trials, the superiority of MPT was shown in terms of both RR and long-term outcome (PFS/OS), even in patients >75 years of age (see Table 2). A fourth study28 is ongoing and enrolled 362 patients with a mean age of 75 years. Results of an interim analysis showed a better RR and time to progression in the MPT group than in the MP group, but did not show any improvement in PFS or OS. In the final clinical trial,29 the addition of thalidomide to MP resulted in a significantly better RR (66% in MPT versus 47% in MP) and a significantly better EFS and PFS, but did not confirm a survival advantage of MPT.

In all of these studies, the main adverse events of regimens containing thalidomide were neutropenia, DVT, PN and infection. The use of anticoagulants helps to reduce the DVT rate. In elderly patients, it is recommended not to exceed a dose of 100mg/day, and eventually to reduce or discontinue thalidomide in cases of worsening paresthesia, neuropathic pain and motor deficits. In fact, even if the studies do not show a clear OS advantage, MPT is regarded as the new standard regimen for newly diagnosed elderly or unfit myeloma patients.

Lenalidomide, Melphalan and Prednisone

A phase I/II dose-escalating open-label study has evaluated the safety and efficacy of lenalidomide in combination with MP30 in 50 newly diagnosed MM patients who were not eligible for ASCT (see Table 2).

The schedule included oral melphalan in doses ranging from 0.18 to 0.25mg/kg on days one to four, prednisone at 2mg/kg on days one to four and lenalidomide at doses ranging from 5 to 10mg on days one to 21 every 28 days for nine cycles, followed by maintenance therapy with lenalidomide alone. Aspirin was given as thromboprophylaxis.

The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was defined as 0.18mg/kg melphalan and 10mg/day lenalidomide. With these doses, 81% of patients achieved at least PR, 47.6% achieved VGPR and 23.8% achieved CR. In all patients, one-year EFS was 92% and OS was 100%. At the MTD, grade 3 adverse events included neutropenia (38.1%), thrombocytopenia (14.2%), febrile neutropenia (9.5%), vasculitis (9.5%) and thromboembolism (4.8%). Grade 4 adverse events included neutropenia (14.2%) and thrombocytopenia (9.5%). At the MTD, grade 3/4 adverse events were primarily haematological, while non-haematological adverse effects accounted for <10% of the total, using aspirin prophylaxis. PN was never observed. This study demonstrated that MPR is an active combination in newly diagnosed elderly myeloma patients and represents an effective alternative to MPT. Lenalidomide can be given for a prolonged period of time as maintenance treatment without significant toxicities. A large international study comparing MP, MPR and MPR therapies followed by lenalidomide maintenance therapy is ongoing.

Bortezomib, Melphalan and Prednisone

The encouraging results of a phase I/II trial31,32 that evaluated the combination of MP with bortezomib led to the randomised phase III study VELCADE as Initial Standard Therapy in Multiple Myeloma: Assessment with Melphalan and Prednisone (VISTA),33 which compared VMP with MP for the treatment of elderly newly diagnosed MM patients (see Table 2). Six hundred and eighty-two patients were randomised to receive nine six-week cycles of melphalan (9mg/m2) and prednisone (60mg/m2) on days one to four, either alone or with bortezomib (1.3mg/m2) on days one, four, eight, 11, 22, 25, 29 and 32 during cycles one to four and on days one, eight, 22 and 29 during cycles five to nine. The ORR (PR or better) was 71%, including 30% CR in the VMP group, compared with 35 and 4%, respectively, in the MP group.

Median TTP was 24 months in the bortezomib group versus 16.6 months in the control group, and the hazard ratio for OS was 0.61 for VMP arm (p=0.008). The median duration of response was 19.9 months for the VMP group versus 13.1 months for MP. Haematological adverse events were similar in the two groups. PN, gastrointestinal symptoms and herpes zoster reactivation were more frequent in the VMP arm.

Considering patients with poor prognosis, i.e. those >75 years of age, those with renal impairment and those with cytogenetic abnormalities, there were no significant differences in the VMP arm compared with younger patients, with normal renal function and without cytogenetic abnormalities (CAs), respectively. In patients >75 years of age, the CR rate was 26% versus 32% in younger patients, and there was a slightly lower OS (p=0.17).

This study showed that VMP is an effective treatment for newly diagnosed MM patients not eligible for ASCT. The adverse events, especially PN and herpes zoster reactivation, are slightly higher than with MP, but with appropriate prophylaxis and drug reduction it is possible to decrease the incidence without compromising the efficacy.

Four-drug Combination

The combination of four drugs is emerging as a new approach in the treatment of MM. The association of two new agents with different mechanisms of action and two older consolidated drugs seems to ensure a high RR, including a higher CR rate, which could be translated to a longer PFS and OS. The toxicity may be elevated, but reducing the dosage, prolonging the interval between the single administrations and using prophylaxis, especially for infection and DVT, allow adverse events to be kept under control without compromising efficacy. Two studies are ongoing: one is testing the association of bortezomib–melphalan–prednisone–thalidomide (VMPT) and the other one the combination of lenalidomide–bortezomib–cyclophosphamide– dexamethasone (RVCD).34,35 In both cases, the RR is high, including CR, but a longer follow-up is needed to assess the effects of these approaches on outcome. Table 3 reviews the current data from these two trials.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Elderly Myeloma Patients

Patients >65 years of age are not generally considered eligible for high-dose therapy with melphalan 200mg/m2 (Mel 200) followed by ASCT.

Three studies evaluated the efficacy and safety of a reduced-dose conditioning regimen (melphalan 100mg/m2) followed by ASCT in patients 65–70 years of age. Palumbo et al. compared MP with intermediate-dose therapy (two courses of Mel 100) in patients 50–70 years of age.36 RR was higher in patients who received Mel 100: at three years EFS and OS were 37 and 77%, respectively, in the Mel 100 group versus 16 and 62%, respectively, in MP patients. Similar results were seen in patients 65–70 years of age, with a median OS of 37.2 months in the MP arm versus 58 months in the Mel 100 group. Haematological toxicity, fever of unknown origin and mucositis were more frequent and had a longer median duration in the Mel 100 group.

In the IFM 99-06 trial, in patients 65–75 years of age, ASCT was superior in terms of RR, but there was no difference in terms of OS and EFS compared with MP. Moreover, median OS was significantly longer in MPT patients than in those who received intermediate-dose therapy (51.6 versus 38.3 months, respectively).26

In the third study, newly diagnosed MM patients 65–75 years of age received bortezomib, pegylated lyposomal doxorubicin and dexamethasone (PAD) induction regimen followed by a tandem Mel 100 conditioning regimen and ASCT. After stem cell transplantation, patients received consolidation with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (RD four cycles) followed by lenalidomide alone as maintenance until progression of disease.37 The ORR improved from induction to consolidation therapy, with 100% of patients obtaining at least PR, including 53% immunofixationnegative CR after RD consolidation. After a median follow-up of 14 months, one-year PFS and OS were both 92%. The use of high-dose therapy in elderly patients is controversial. These studies showed that in fit patients 65–70 years of age, intermediate-dose melphalan (Mel 100) followed by ASCT can be administered. The high RR and the long-term outcome obtained with the new-drug-containing regimen raise the question of whether there is still a place for ASCT, especially in elderly patients. More comparative phase III trials between new agents containing CC and high-dose therapy are required to answer this question.

Treatment-related Adverse Events and Their Management

Thalidomide, lenalidomide and bortezomib may not be considered CC. They are considered target therapy, as they act more on myeloma cells and on the bone marrow microenviroment. Unfortunately, this has not completely eliminated the effect of these drugs on normal cells that may cause some toxicities, but are generally manageable.

In elderly MM patients, the presence of co-morbidities and, in general, age-related frailty may increase the risk of developing significant adverse events, both myeloma- and therapy-related.38 The prompt reduction of drug doses and opportune prophylaxis allow the incidence of toxicities to be reduced, without compromising efficacy. Table 4 summarises the more frequent treatment-related adverse events and their management. Table 5 summarises the dose reduction of drugs, according to the age of patients.

Conclusion

MM is a malignancy that mainly affects people >65 years of age. In the past, the best therapeutic option for these patients was a melpahalan and prednisone combination. In fact, MP plus thalidomide (MPT) is considered the gold standard of therapy for patients not eligible for ASCT. The association of bortezomib with MP was shown to be an effective and safe combination as well, with the potential to overcome the bad prognosis related to cytogenetic abnormalities, such as deletion of chromosome 13 or renal impairment. The absence of PN makes MPR the best alternative for patients with a positive anamensis for this kind of neurological disease. In general, the association of MP with the new drugs represents a balanced choice between safety and efficacy. High-dose dexamethasone with thalidomide, lenalidomide or bortezomib is too toxic for the elderly; however, it represents a good induction regimen for patients eligible for ASCT. The association of a reduced dose of dexamethasone with doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide and the new agents is under evaluation.

Four-drug combinations are emerging as possible alternative treatments that induce a higher ORR, including a high CR rate and potentially longer PFS/OS. However, longer follow-up is needed to evaluate these more complex regimens.

ASCT is not considered the first therapeutic choice for elderly patients, except in the US. In Europe, for patients ≤70 years of age who are particularly fit, it is possible to explore this option by reducing the dose of conditioning regimen (Mel 100).

The elderly are fragile patients, as they often have other concomitant diseases that can complicate the course of myeloma treatment, with more frequent treatment-related complications. In these patients, a balanced choice between efficacy and safety includes the reduction of the standard dose of therapy, eventually prolonging the exposition and the administration of appropriate prophylaxis, especially for infection and DVT. ■