During the last decade, significant therapeutic progress has been made in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). MM is the second most common haematological malignancy. It is a highly symptomatic disease with the following common symptoms: osteolytic skeletal damage, renal impairment, anaemia, hypercalcaemia and severe infections. Historically, the outcome of MM patients was very dismal with the median overall survival reaching only a few years.1

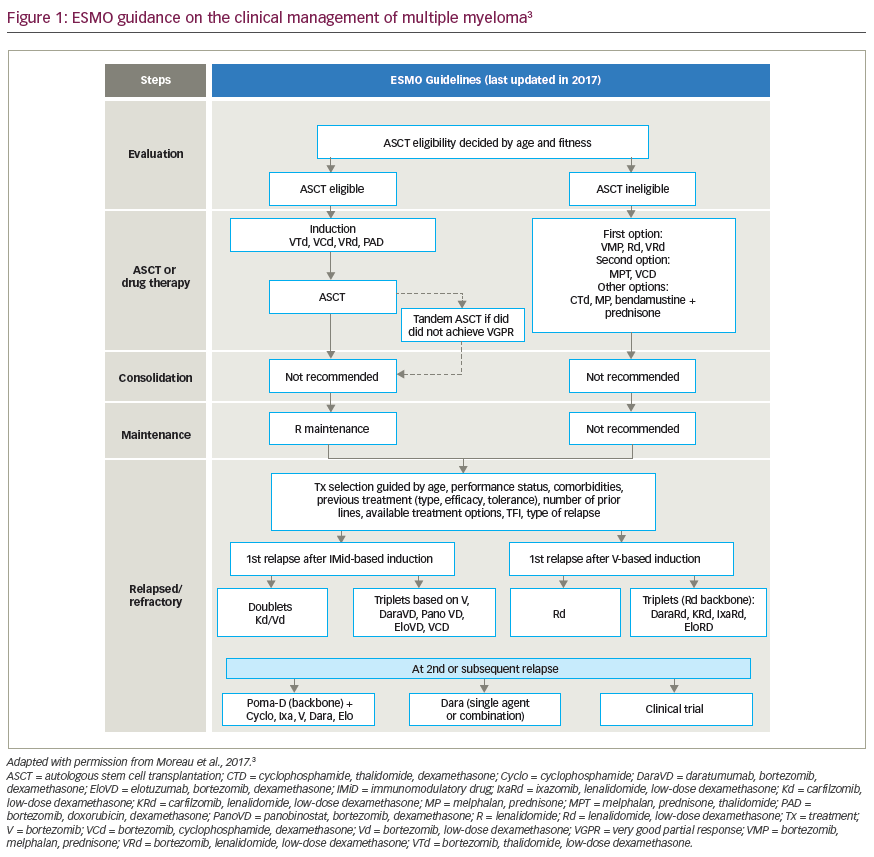

However, the recent therapeutic progress made in the treatment of MM is impressive. A first important therapeutic milestone was the introduction of autologous stem-cell transplantation in the mid-1990s for patients up to the age of 65–70 years.2 In the last decade, several new molecules with strong anti-myeloma activity were introduced including the firstin- class proteasome inhibitor bortezomib,3 and the immunomodulatory drugs thalidomide,4 lenalidomide5 and, more recently, pomalidomide.6 Initially registered for relapsed and refractory MM patients, these agents have gradually moved to the front-line and have reshaped the current landscape of myeloma treatment. Consequently, the outcome of MM patients has significantly improved, and current survival rates can approach 10 years in transplant candidates and exceed 5 years in elderly patients. However, cure remains exceptional.7 In other words, the natural MM disease course is a succession of treatment, remission and relapse, until the therapeutic possibilities are exhausted, or the patient dies from a myeloma-related complication, or another disease. Optimisation of treatment in MM requires not only active anti-myeloma drugs but also sensitive techniques to monitor and guide the treatment strategy. The M-protein, detectable in serum and/or urine in >95 % of MM patients, can be considered as a myeloma-specific ‘tumour marker’. The standard panel for myeloma response measurement consists of M-protein measurement, together with imaging of lytic lesions or plasmacytomas by conventional X-ray and more recently by computerised tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET)8 and intermittent bone marrow aspirations. In 1998, the European Bone Marrow Transplant Group myeloma response criteria were introduced that defined four levels of responses: complete (CR), partial (PR), minimal (mR) response and stable disease. However, in that era, CR was rare, but outcome was sometimes very different in partially responsive patients. In order to refine the outcome of the large cohort of PR patients, the subgroups of ‘very good partial response’ (VGPR) and ‘near CR’ (nCR) were introduced in 2006 in the International Uniform Response Criteria (IURC) for MM.9 Although some studies were in favour of longer disease control for patients in VGPR or nCR versus PR, it has become clear, both in transplant and non-transplant candidates, that achieving sustained CR is the best guarantee for prolonged progression-free and overall survival.10,11 An exception to this general rule is the small subgroup of patients where the residual disease goes back into a dormant or smouldering (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance [MGUS]-like) phase.12 In the current era of highly active anti-myeloma treatment regimens, CR rates can be achieved in one-third to half of the patients13; a figure believed to further increase in the following years now that a new wave of therapeutic agents like second-generation proteasome inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies are entering the clinic.

However, in contrast with many other cancers, where CR is a surrogate marker for cure, the majority of MM patients achieving a ‘conventional CR will relapse because of the persistence of minimal residual disease (or MRD) beyond the detection limits of standard response assays. Therefore, myeloma response criteria have been further upgraded with three categories by incorporation of highly sensitive techniques for detection of MRD.14 Stringent CR (sCR) requires normalisation of serum-free light chains without a detectable paraprotein in serum and urine, and in the absence of clonal bone marrow plasma cells or new or progressing plasmacytomas. With the implementation of multicolour flowcytometry and molecular techniques like sequencing, the categories immunophenotypic (iCR) and molecular CR (mCR) were introduced. The latter techniques allow detecting one clonal cell in a background of 105–106 normal cells. Patients achieving sCR,15 iCR16 or mCR17 have significantly longer remissions compared with those with detectable residual disease. However, in contrast to other diseases, for instance chronic myeloid leukaemia, myeloma treatment response cannot be measured by one single assay. By nature, MM has a ‘patchy’ or diffuse pattern of infiltration in the marrow, and it can spread to other sites by contiguity or through the bloodstream. The combination of the above-mentioned serum, urine and bone marrow tests combined with highly sensitive imaging techniques such whole body MRI and PET-CT offers future opportunities for a more ‘holistic’ and very sensitive response assessment in myeloma.

Finally, the question remains to what extent response assessment can optimise treatment for newly diagnosed MM patients. Transplantcandidates are currently treated with a sequence of a proteasome inhibitor-based induction regimen, stem-cell collection, transplantation, consolidation and, eventually, maintenance treatment. As long as residual disease is detectable, there is a treatment target. But several ongoing clinical trials will help us in the near future to answer the question – which groups of patients will particularly benefit from prolonged treatment or treatment beyond the level of undetectable disease. For the time being, response assessment should be carried out regularly and with the most sensitive assays. Keeping in mind the current cost of novel anti-myeloma drugs, the extra expenses of the response assessment can add significant clinical benefit to myeloma patients.