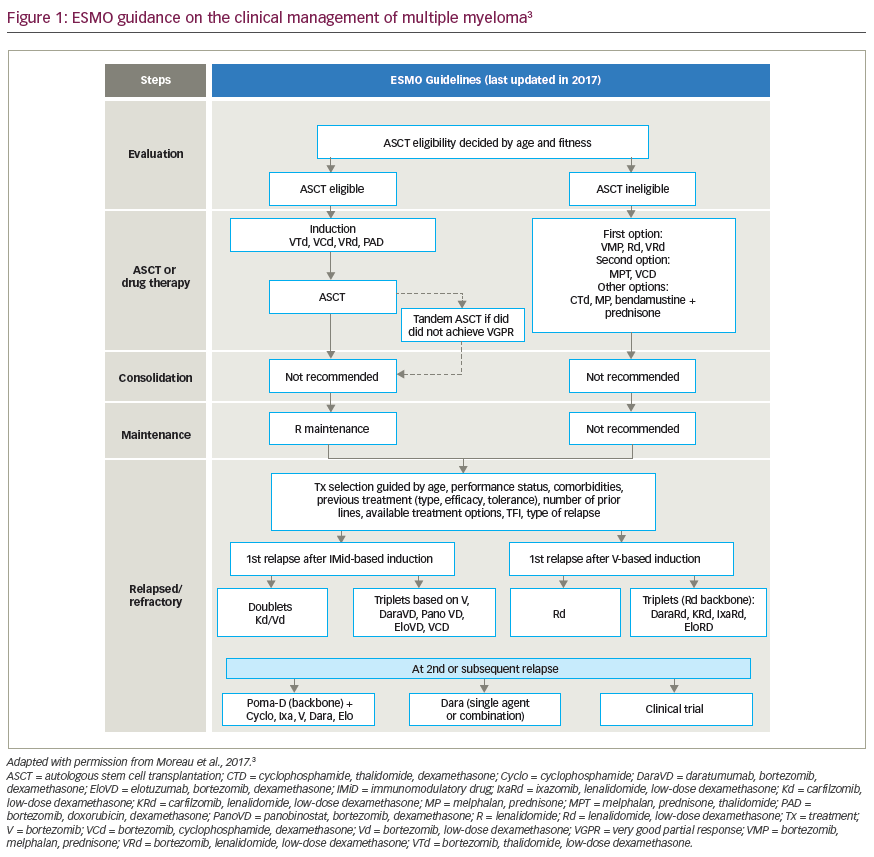

Patients with symptomatic MM, which is defined by the presence of organ damage (calcium [hypercalcaemia], renal insufficiency, anaemia or bone lesions, the so-called CRAB criteria) should be treated immediately. Treatment choice should be based on the patient’s characteristics (age and presence of co-morbidities) and on scientific evidence. Patients treated with conventional chemotherapy have a median survival of three to four years.5 The use of high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous or allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) has improved the outcome and survival and is now considered the standard of care for symptomatic MM patients under 65 years of age with good performance status.6,7 Agents targeting both the MM cells and the bone marrow microenviroment, such as thalidomide, lenalidomide and bortezomib, have shown significant activity in MM. Combinations of these agents with steroids, alkylating agents or anthracyclines have significantly improved response rate (RR) and progression-free survival (PFS). No difference in overall survival (OS) was reported during a 24-year period from 1971 to 1994 in a large group of newly diagnosed myeloma patients; there was a trend towards improvement between 1995 and 2000 and a statistically significant benefit in OS was shown between 2001 and 2006.8 These data suggest that ASCT was responsible for the trends seen during 1994–2000, while novel agents contributed to the improvement observed since 2001.

Multiple Myeloma and Age

Almost two-thirds of patients with MM are observed with increasing age.3 The optimal treatment for elderly patients has not yet been established, partly because these patients tend to be under-represented in clinical trials, which often report a median age for newly diagnosed patients of around 60 years. Commonly, 65 years of age is the lower limit used to define old patients. There is a significant difference in outcome according to age. In a study conducted in the UK on 855 patients, the median survival for patients over 65 years of age was 18 months compared with 42 months in younger patients, regardless of the type of therapy received.9 Other studies have confirmed this finding.10,11 No significant differences in tumour biology have been elucidated to explain the survival difference between older and younger patients. The adverse prognostic impact of advanced age in myeloma is predominantly related to a combination of factors, including co-morbidity, performance status, decreased physiological reserve, social support, referral bias and, especially, under-treatment of the tumour.12 The outcome for elderly MM patients after conventional chemotherapy has not changed dramatically since the introduction of the melphalan–prednisone (MP) combination. A more intensive approach can be safely offered to selected elderly patients, always taking into account that anagraphic age may considerably differ from biological age. Some patients still remain unsuitable for ASCT. The data available from the most recent studies suggest that the combination of conventional chemotherapy with the new drugs has the potential to improve the outcome of the elderly MM patients. Front-line Therapy in Elderly Patients or Young Patients Inelegible for Autologous Stem-cell Transplantation

Patients who are not transplant candidates have been treated for years with standard alkylating agent therapy. In the age group between 65 and 70 years, intermediate-dose melphalan appears a suitable option. In a randomised study, patients 65–70 years of age received melphalan 100mg/m2 or MP, and the reduced-intensity ASCT programme was superior to MP.13 In another study, patients 65–75 years of age received melphalan 100mg/m2 or MP; ASCT was superior to MP in terms of RR, but not in terms of PFS and OS.14 In the first study, 22% of patients did not complete the assigned treatment; in the second trial, 37% of patients did not complete it. These results confirm the importance of balancing efficacy and toxicities to improve outcome. The discovery of novel therapies targeting MM cells and the bone marrow microenviroment has changed the treatment paradigm of MM therapy, especially in the elderly population.

Thalidomide-based Regimens

In younger patients, thalidomide and dexamethasone (thal/dex) significantly improves PFS in comparison with high-dose dexamethasone alone.15 In elderly patients, thal/dex was compared with MP in a randomised study.16 Despite a higher RR with thal/dex, patients treated with MP presented a significantly longer survival (p=0.02), particularly evident in patients over 72 years of age. Patients on thal/dex experienced more grade 2–3 neuropathy (25%) and skin toxicity (12%) compared with those on MP (8 versus 3%, respectively). Thromboembolic complications were seen in 8% of patients receiving thal/dex and in 3% of patients receiving MP. The higher toxic rate of the thal/dex regimen can explain the lower efficacy of thal/dex in the elderly population. These results indicated that melphalan represents an essential drug that should be included in every induction regimen, while dexamethasone should not be routinely recommended as a first-line treatment in elderly patients. Four different randomised studies assessed the combination MP plus thalidomide (MPT).14,17–19 Patients treated with MPT experienced higher partial response (PR) rates (57–76%) and longer PFS (median 15–28 months) compared with patients receiving MP; in two studies longer PFS translated into a significant improvement in OS. Thalidomide therapy was well-tolerated; the main toxicities were neuropathy, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), infections and gastrointestinal toxicity that did not, however, influence survival even in a elderly population of patients (>75 years of age).18 MPT was associated with a significant improvement in survival and a significantly lower extra-haematological toxicity when ASCT was compared with intermediate-dose melphalan (Mel100) in patients 65–75 years of age.14

These data strongly support MPT as the new standard of care for elderly myeloma patients. In the Medical Research Council (MRC) Myeloma IX trial, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide and dexamethasone (CTD) was compared with MP in 900 patients.20 In the CTD group, the PR rate (82 versus 49%) and the CR rates (23 versus 6%) were significantly superior in the CTD group.20 Unfortunately, data on remission durations are not available, and if they are also superior to MP, the CTD regimen should be added as alternative standard front-line approach for elderly patients.

Lenalidomide-based Regimens

In a phase I/II Italian trial, the dosing, safety and efficacy of melphalan plus prednisone and lenalidomide (MPR) in newly diagnosed elderly myeloma patients was assessed.21 The maximum tolerated dose was considered: melphalan at 0.18mg/kg on days one to four, prednisone 2mg/kg on days one to four and lenalidomide at 10mg on days one to 21 every 28 days for nine cycles. Aspirin was given as a prophylaxis for thrombosis. Eighty-five per cent of patients achieved at least PR and 23.8% achieved immunofixation negative complete response (CR). Grade 3–4 adverse events were mainly related to haematological toxicities (neutropenia 66%). Severe non-haematological side effects were less frequent and included febrile neutropenia (8%), cutaneous rash (10%)and thromboembolism (6%). This study formed the basis for the ongoing international phase III study comparing MP versus MPR. Bortezomib-based Regimens

A Spanish co-operative group conducted a large phase I/II trial evaluating the combination of oral MP plus bortezomib (MPV) in newly diagnosed elderly MM patients.22,23 The association showed encouraging results: the PR rate was 89%, including 32% immunofixation-negative CR, and half of them achieved immunophenotypic remission (no detectable plasma cells at 10-4 to 10-5 sensitivity). The PFS at 16 months for MPV patients was significantly prolonged in comparison with historical controls treated with MP only (91 versus 66%); similarly, OS at 16 months was improved (90 versus 62%). The treatment appeared to be more toxic in patients over 75 years of age. These data have recently been confirmed in a large randomised trial comparing MPV with MP and have provided the background to defining MPV as an alternative standard of care for elderly patients.24 Results demonstrate that VMP was highly superior to MP for CR rate, time to progression (TTP) and OS. The TTP benefit was seen consistently across patient subgroups and efficacy was not affected by renal function or high-risk disease, confirming the results of a phase II study evaluating the same regimen.23 This regimen showed a significant increase in gastrointestinal toxicities, peripheral neuropathy, fatigue and infections; the DVT rate was low in both patient subgroups.24

The efficacy of these new regimens should be balanced against their higher toxicities: in the presence of high risk of thromboembolism, MPV could be the preferable option; in the presence of peripheral neuropathy, MPR should be considered; in patients with renal insufficiency, MPV is better tolerated; and MPT should be considered if costs are a concern. Oral treatment should also be balanced versus intravenous treatment, which requires frequent admittance to the hospital.

Front-line Therapy in Young Patients Elegible for Autologous Stem-cell Transplantation

Vincristine–doxorubicin–dexamethasone (VAD) and dexamethasone alone were used for years as pre-transplant induction therapy. Recently, new drugs have been incorporated into pre-transplant regimens with promising preliminary results. Table 1 summarises the front-line therapies available for the elderly. Thalidomide-based Regimens

The Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group (ECOG) compared thal/dex with high-dose dexamethasone (HD) alone in 470 newly diagnosed myeloma patients. The overall RR was significantly higher with thal/dex compared with HD (63 versus 46%; p<0.001), with a significantly longer TTP (median 22.6 versus 6.5 months; p<0.001). DVT was more frequent with thal/dex (18.8 versus 5.6%). Overall, grade 3–4 non-haematological toxicities were more frequently seen with thal/dex (79.5 versus 64.2%; p<0.001).15 In another trial, induction with thal/dex was compared with a VAD-like regimen followed by high-dose therapy and ASCT in 204 patients. The verygood PR (VGPR) rate was higher in the thal/dex group (34.7 versus 12.6%; p=0.002) before ASCT, but this benefit was not observed at six months post-transplant (VGPR 44.4 versus 41.7%; p=0.87).25 Based on the results of the trials on thal/dex, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for this combination for the treatment of newly diagnosed MM. The introduction of thalidomide into the high-dose therapy, followed by ASCT, induced a higher CR rate (62 versus 43%) and improved five-year event-free survival (EFS) (56 versus 44%) compared with high-dose therapy without thalidomide.26 Unfortunately, the five-year OS was similar in both groups (p=0.9). In the thalidomide group, a higher rate of thromboembolism (30 versus 17%) and peripheral neuropathy (27 versus 17%) were reported.26 In the MRC Myeloma IX trial, which recruited 900 patients, CTD was compared with cyclophosphamide-VAD (C-VAD) as an induction regimen before ASCT. In a preliminary analysis, the CR rate was higher after CTD (20.3 versus 11.7%), and this difference was maintained at 100 days post-ASCT (58.2 versus 15).20 In two German–Dutch parallel phase III multicentre trials, the standard VAD regimen was compared with thal/dex plus doxorubicin (TAD): higher VGPR rates after induction and after ASCT were reported, but results on survival are not yet available.27 Thalidomide-based regimens provided superior rates of response when used as induction therapy in comparison with standard treatment. The efficacy of this combination must be balanced against the greater toxicity and the need for antithrombotic prophylaxis. The presence of a central venous catheter, co-morbidities and immobilisation, as well as the administration of HD, in multiagent chemotherapy may significantly increase the risk of thromboembolic events. In these conditions, coumadin (target international normalised ratio [INR] 2–3) or low-molecular-weight heparin (equivalent of enoxaparin 40mg once daily) are suggested for the first four to six months of therapy. In patients lacking these risk factors, aspirin can be used.28

< b>Lenalidomide–Dexamethasone

The lenalidomide–dexamethasone (rev/dex) combination has demonstrated significant activity in different trials. In a recent study, 198 patients were randomly assigned to receive rev/dex or dexamethasone alone,29 with a significantly higher CR rate in the rev/dex group (22.4%). The superior RR translated in prolonged remission duration: the one-year PFS was 77% in the rev/dex group and 55% in the dexamethasone group (p= 0.002). ECOG tested rev with HD (40mg pulsed days 1–4, 8–11 and 15–18) versus rev/low-dose dex (40mg dexamethasone once weekly).30 Toxicity rates were significantly higher with rev/HD compared with rev/low-dose dex, with a low (first four months) early mortality rate in both groups (5 and 0.5%). The DVT rates observed in this study were also low, making rev/low-dose dex one of the safest pre-transplant induction regimens for myeloma. In a phase II trial, rev/dex was combined with claritromycin (biaxin), following the biaxin (clarithromycin)/revlimid (lenalidomide)/dexa- methasone (BiRD) regimen, the CR rate was high (38.9%), including 30.6% of stringent CR (immunofixation negative plus normal free-light chain ratio, plus a negative marrow biopsy by immunohistochemistry).31 These studies confirm the high efficacy of lenalidomide in the upfront treatment of younger myeloma patients with a better safety profile compared with the parent compound thalidomide. In particular, the combination of lenalidomide with low-dose dexamethasone appears to be the more suitable options in this setting. Bortezomib-based Regimens

The combination bortezomib and dexamethasone (bort/dex) showed an verall RR of 66%, including 21% CR/nCR and 10% VGPR.32 The most common side effects were gastrointestinal symptoms, peripheral neuropathy and fatigue. Peripheral neuropathy was grade 2–3 in 14% of patients. DVT and haematological toxicity greater than grade 2 were not observed. Grade 3 infections were recorded in five patients, including three who had herpes zoster infections. In another study, bort/dex has been administered following an alternating schedule (bortezomib at 1.3mg/mq bi-weekly, cycles one, three and five only) as induction therapy followed by ASCT. This alternating schedule induced a PR rate of 65%, including a CR rate of 12.5% and a VGPR of 10%. Toxicity was low with no grade 3–4 peripheral neuropathy or grade 2–4 thrombocytopenia. Chromosome 13 deletion, t(4,14) and t(14,16) did not have a negative impact on response.33 Bort/dex has been compared with VAD as induction therapy prior to ASCT in a randomised trial, showing a significantly higher CR plus nCR rate (21.3 versus 8.3%), which was maintained after ASCT (38 versus 28%).34 In a recent randomised trial, bortezomib–dexamethasone–thalidomide (VTD) was compared with hal/dex as an induction treatment before double ASCT. The CR plus nCR rate was 36% with VTD and 9% with thal/dex, and 57% with VTD plus ASCT and 28% with thal/dex plus ASCT.35 In all of these studies, additional follow-up is required to verify if this difference translates into a significant PFS advantage. Doxorubicin combined with bort/dex (PAD) has been compared with VAD in another randomised trial; the results are not yet available, but different phase II studies suggest a substantial activity of this regimen.36,37 In a phase II study, 100 patients received bortezomib, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and dexamethasone (PLD) before reduced-intensity ASCT (melphalan 100mg/m2). After induction with PAD, the CR plus nCR rate was 23% and increased to 60% with PAD plus reduced-intensity ASCT.38 The risk of DVT is low with bortezomib (<5%), while peripheral neuropathy can be higher, but alternating regimens significantly reduced such a risk. Table 1 summarises the front-line treatments available for younger patients.

New Maintenance Approaches

In a large study, patients under 65 years of age were randomly assigned to receive no maintenance, pamidronate or pamidronate plus thalidomide.39 The three-year post-randomisation probability of EFS (p<0.009) and the four-year OS (p<0.04) were significantly prolonged in patients who received thalidomide. In another study, thalidomide– prednisone was compared with prednisone alone as maintenance therapy after ASCT, confirming improved one-year PFS and two-year OS for the thalidomide group.40 In both studies, grade 3–4 peripheral neuropathy were significantly more prominent in the thalidomide group then in the controls. More recently, newly diagnosed patients received thal/dex as induction; they were then randomly assigned to tandem ASCT or single ASCT followed by thalidomide maintenance.41 The three-year PFS was 57% in the double ASCT group and 85% in the single ASCT group followed by thalidomide maintenance (p=0.02). In this study, the advantage of maintenance approach was shown even in patients previously treated with thal/dex as induction therapy. Additional studies are needed to determine the role of routine maintenance in myeloma, especially the use of lenalidomide that has a better safety profile than thalidomide for long-term maintenance.

Treatment at Relapse

The outcome of MM patients has significantly improved over the last decade, but the disease remains incurable. Once the patient relapses after upfront treatment, the durations of subsequent responses to rescue therapies are progressively shortened. When approaching a relapsed patient it is important to consider response and toxicities related to prior therapies: relapses occurring later than 18 months from previous therapy may be retreated with the same regimen, if well tolerated. Table 2 summarises the treatments available for relapsed patients. Thalidomide

The therapeutic efficacy of Thal has been confirmed in numerous trials in refractory/relapsed MM patients. Thal/dex has been compared with HD in a phase III trial and preliminary results demonstrated higher RRs and longer one-year PFS in patients treated with the two drugs.42 The addition of cyclophosphamide to thal/dex may further increase RRs that yields durable responses (57% EFS at two years).43

Lenalidomide

Rev/dex has received FDA approval based on the results of two randomised studies comparing rev/dex with HD in patients who have received at least one prior treatment. In both studies, the rev/dex was associated with significantly higher RR (60 versus 22%), CR rate (15 versus 2%) a longer TTP (median 11.1 versus 4.7 months) and a longer median OS (35 versus 31 months).44,45 Rev has also been evaluated in relapse/refractory MM patients in combination with anthracyclines, such as adriamycin plus dex or liposomal doxorubicin, vincristine and dex (DVd- R) and cyclophosphamide showing a remarkable activity.46,47

Bortezomib

A phase III trial comparing bortezomib and HD reported a significant improvement in TTP and one-year OS in bortezomib-treated patients;48 and the addition of dexamethasone was associated with improved responses.49 A phase III trial comparing PAD with bortezomib alone showed that the use of the drug combination significantly extends both TTP and OS.50 The FDA has approved a regimen consisting of bortezomib plus PLD for patients who have received at least one previous therapy (not including bortezomib). Combination including chemotherapy regimes has shown higher RRs in comparison with dexamethasone alone. A chemotherapy agent should be added in the presence of a suboptimal response to new drugs with steroids; a sequential approach should be adopted, alternating different drugs following subsequent relapses.