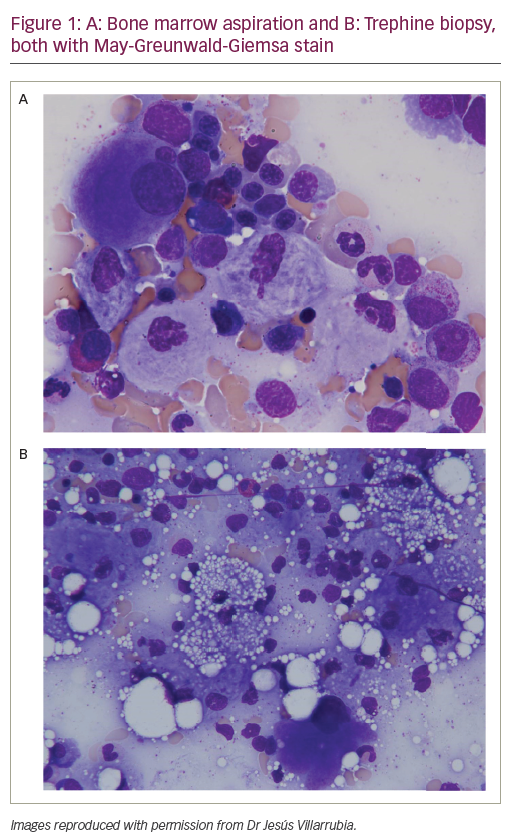

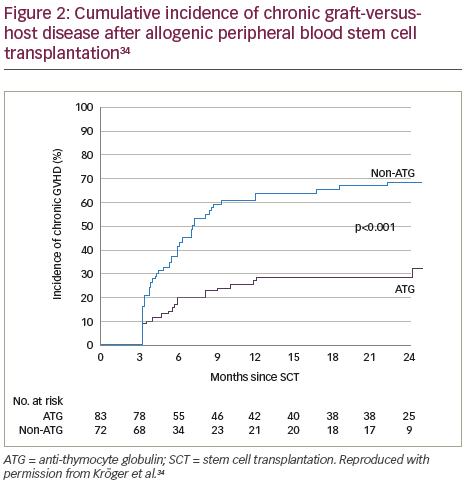

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is one of the major complications of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) resulting from a complex interaction between the donor-derived immune system and recipient organ.1 While acute GVHD is a distinctive syndrome consisting of the development of mainly dermatitis, hepatitis and enteritis, chronic GVHD describes a more diverse syndrome, potentially affecting almost all organs and tissues in the body. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Project has proposed two subcategories for chronic GVHD: classic and overlap syndrome (Figure 1). These syndromes, which have been shown to have clinical validity,2 are based on clinical features rather than time of onset. This is due to recognition that both classical features of chronic GVHD can occur within 100 days post-HSCT and that features of acute and chronic GVHD could occur together.3 Therapies such as steroids that are effective in treating acute GVHD might be much less effective for chronic GVHD and this together with the differences in clinical presentation, suggest that unique physiologic mechanisms may be involved in chronic GVHD.4 Unlike acute GVHD, which is mediated almost entirely by donor T cells, chronic GVHD immune pathology is more complicated and donor B cells have also been found to play an important role.5

In the literature the incidence of chronic GVHD following allo-HSCT ranges from 6–80%, according to presence of risk factors and diagnostic criteria used.3,6–8 Several potential risk factors have been described, including transplant from donors other than a matched sibling,9,10 older recipients11,12 and the use of peripheral blood graft.13–15

Chronic GVHD can lead to later illness, including immune dysfunction and infection risk, a reduction in quality of life and a decline in life expectancy.6,17 In a records review of 10,632 patients who were alive and disease free 2 years after receiving myeloablative allogeneic HCT before 2004, 3,788 patients were studied for 10 or more years.16 The probability of being alive 10 years post-HCT was 85%. Older age and chronic GVHD were the main risk factors for late death. In a cohort of 2,574 patients who survived without recurrence for 5 years or more post- HCT, the estimated survival of the cohort was 80.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] 78.1–82.6%). The leading causes of additional deaths, in descending order, were second malignancies and recurrent disease, GVHD, respiratory diseases and cardiovascular diseases.

A US report in 2011 from the Chronic GVHD Consortium revealed that patients with moderate and severe chronic GVHD had physical component scores comparable with scores reported for systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis. They also had greater impairment compared with common chronic conditions including diabetes, hypertension, and chronic lung disease.18 A comparison of the mean Short Form-36 scores between chronic GVHD patients and the normal US population showed significant impairment

for chronic GVHD patients across multiple domains, including physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning and physical component scores.18

The purpose of this article is to provide a succinct overview of the unique role of anti-human T-lymphocyte immune globulin (ATLG) in the prevention of chronic GVHD.

Prevention of GVHD

None of the current calcineurin-based pharmacological approaches (such as cyclosporine or tacrolimus) that have been successful in acute GVHD prophylaxis have shown a major impact on chronic GVHD in randomised trials.19–23 However, ex vivo T-cell depletion can reduce chronic GVHD, but the approach is limited by a higher rate of malignancy relapse and infections, which are associated with a lack of survival advantage or even with reduced survival.24,25 In a prospective study, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide reduced the risk of both acute and chronic GVHD, although data from randomised studies are lacking. There exists the concern that some strategies aimed at addressing the GVHD effect might impair the beneficial graft-versus-leukaemia (GVL) effect, increasing the risk for relapse.26 Animal and human studies of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation have demonstrated that immunological non-identity between donor and recipient is responsible for a GVL effect.27,28 The recognition of the GVL effect is now driving the evolution of allogeneic stem cell transplantation towards an immunotherapeutic approach.

Anti-human T-lymphocyte immune globulin

The use of ATLG and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) has been shown to lead to a reduced incidence of chronic GVHD after stem cell transplantation from an unrelated donor.29–31 In a prospective, randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase III trial (n=202), the addition of Grafalon®(ATLG, formerly known as ATG-Fresenius-S [Neovii Pharmaceuticals AG, Rapperswil, Switzerland]) to GVHD prophylaxis with ciclosporin and methotrexate resulted in decreased incidence of acute and chronic GVHD.29 This was achieved without

an increase in relapse or non-relapse mortality, and without compromising overall survival. Small, retrospective studies have also suggested the benefits of this approach after human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical transplantation.32,33

Anti-human T-lymphocyte immune globulin in a myeloablative conditioning regimen

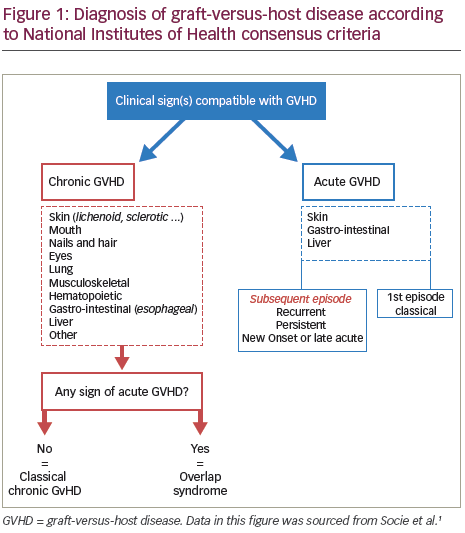

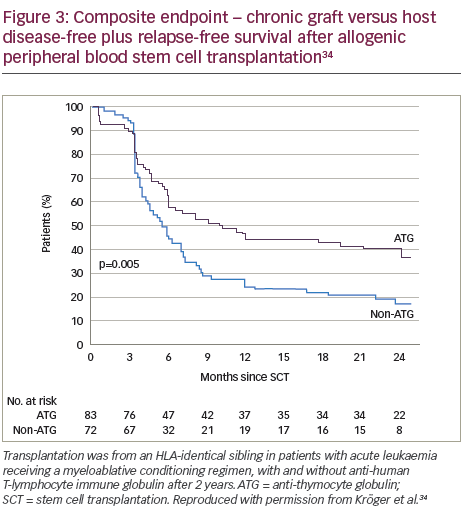

A recent prospective, multicentre, open-label, randomised phase III study (n=168) showed that ATLG inclusion in a myeloablative conditioning regimen for patients in complete remission from acute leukaemia who received peripheral blood stem cells from an HLA-identical sibling, resulted in a significantly lower rate of chronic GVHD post-allogeneic transplantation compared with those receiving the same regimen without ATLG.34 Patients in the ATLG group received a dose of 10 mg/kg, on 3, 2 and 1 days prior to transplantation of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cells from an HLA-identical donor. The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 2 years was 32.2% in the patients (n=83) who received ATLG (95% CI 22.1–46.7) and 68.7% in those patients (n=72) who did not receive ATLG (95% CI 58.4–80.7; p<0.001) (Figure 2). In addition, on the composite endpoint of chronic-free and relapse-free survival at 2 years, the rate was significantly improved for the ATLG group versus the non-ATLG group (36.6% versus 16.8%; p=0.005) (Figure 3). The rate of 2-year relapse free survival was similar between the two groups (59.4% in the ATLG group [95% CI, 47.8–69.2] and 64.6% in the non-ATLG group [95% CI, 50.9–75.3], respectively; p=0.21). The rate of overall survival was likewise similar between the ATLG and non-ATLG groups (74.1% [95% CI, 62.7–82.5] and 77.9% [95% CI, 66.1–86.1], respectively). The median times to leukocyte engraftment (absolute neutrophil count, ≥0.5 × 109 per litre) and platelet engraftment (platelet count, ≥20 × 109 per litre) were statistically significantly longer in the ATLG group compared with the non-ATLG group: 18 days (range, 10–31) versus 15 days (range, 11–34; p<0.001).

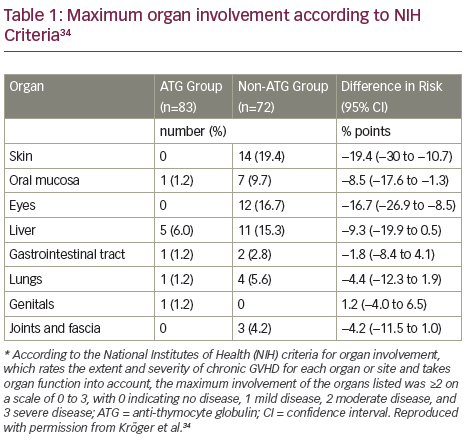

According to NIH scores, there was less chronic GVHD involvement of grade 2 or higher in the ATLG group than in the non-ATLG group in all organs except genital organs (Table 1).34 In addition, there was significantly less chronic GVHD involvement of the skin, the mouth and the eyes. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the rates of relapse, infectious complications, acute GVHD or adverse events.

This is an open study and this, as well as the subjective nature of GVHD grading, represents important limitations of this study. Possible selection bias is another limitation. The patients in the ATG group were aware of group assignment which means that the potential of bias in grading the chronic GVHD cannot be ruled out. In addition, the rate of the composite end-point of 2-year survival free from chronic GVHD and freedom from relapse was significantly higher among those who received ATG than among those who did not (37% versus 17%). The study ended at 2 years and longer-term follow-up data are unfortunately not available.

Conclusions

ATLG, as part of a myeloablative conditioning regimen, administered before transplantation of peripheral-blood stem cells from HLA-identical siblings led to a significantly lower rate of chronic GVHD.34 There was no increased rate of relapse in the patients who received ATLG compared with those who did not, hence no evidence of a reduced GVL effect in ATLG-treated patients. The pathophysiology and immunobiology involved in GVHD and GVL requires further investigation. More data are required on reduced intensity regimens in the same setting and on the long-term effect of ATLG on survival and GVHD relapses beyond 2 years. In addition, improved understanding of the pathophysiology of chronic GVHD will facilitate the design of more prevention studies.