There has been renewed interest in the last decade in terms of laboratory measurement and clinical application of thrombin-generation assays. While these methods have found their place as a useful research tool, the question remains whether they will be routinely applied to the diagnosis of haemostatic disorders and/or the monitoring of anticoagulant therapy. Indeed, the evolution of methods that accurately and specifically measure continuous in vitro thrombin generation to more closely reflect in vivo haemostasis has opened up the possibility that a single, easy-to-perform test may potentially overcome the limitations of currently used coagulation assays.

Thrombin Generation

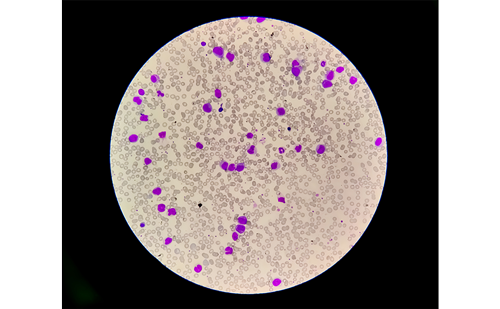

The formation of a blood clot in vivo occurs through a complex series of interactions between platelets, coagulation proteins and enzymes and endothelial cells. Blood coagulation has three major phases with thrombin central to this process: initiation, following vessel damage and subsequent exposure of tissue factor (TF) to the circulating blood to generate small amounts of thrombin; amplification of thrombin through feedback loops involving coagulation factors V, VIII and XI; and propagation, where thrombin generation leads to fibrin formation and stabilisation of the platelet plug.

Thrombin also has important in vivo roles through activation of platelets, activation of coagulation factor XIII to XIIIa to stabilise fibrin monomers, the thrombomodulin-dependent activation of protein C to activated protein C and the activation of thrombin-activated fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) to TAFIa. Readers are referred to more extensive reviews of blood coagulation and in vivo thrombin generation.1–3

Given the importance of thrombin to in vivo haemostasis, its measurement in the laboratory would seem important for the detection of haemostatic abnormalities, including bleeding and thrombotic disorders, as well as for monitoring anticoagulant therapy. Routine diagnostic coagulation tests such as the prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) are limited in that they use platelet-poor plasma (PPP) rather than platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and probably do not accurately reflect in vivo haemostasis. Furthermore, there are a variety of in-house and commercially available methods that measure individual markers of haemostasis that often do not account for their various in vivo interactions. Moreover, it is known that approximately 95% of thrombin generation occurs after the initial formation of fibrin, suggesting that traditional clotting-based tests of coagulation have a major limitation in the approach to laboratory testing where the majority of thrombin that is formed during a clotting reaction is not taken into account when applied to the investigation of bleeding and thrombotic disorders.

The continuous measurement of in vitro thrombin generation in the laboratory has been proposed as a potentially more relevant marker of in vivo haemostasis. Indeed, these methods have improved considerably and have been extensively investigated from a research context, and it is now being assessed whether they can be effectively applied in clinics.

Thrombin-generation Assays

Methods to determine continuous thrombin generation in the laboratory have evolved over more than 50 years.4,5 The earliest methods were poorly standardised and mainly applied as a research tool. Thrombin generation was initially triggered in PRP or PPP in a primary reaction tube, followed by sub-sampling at regular time intervals into a second tube containing fibrinogen for calibration against a thrombin standard.6 As a rule, these assays were labour-intensive and technically demanding. Later versions of thrombin-generation assays evolved to include defibrination of plasma and use of a chromogenic substrate, removing the requirement for sub-sampling. Further improvements included the incorporation of slow-acting fluorogenic substrates, which removed the defibrination step and allowed continuous measurement of thrombin generation in PRP.7–9

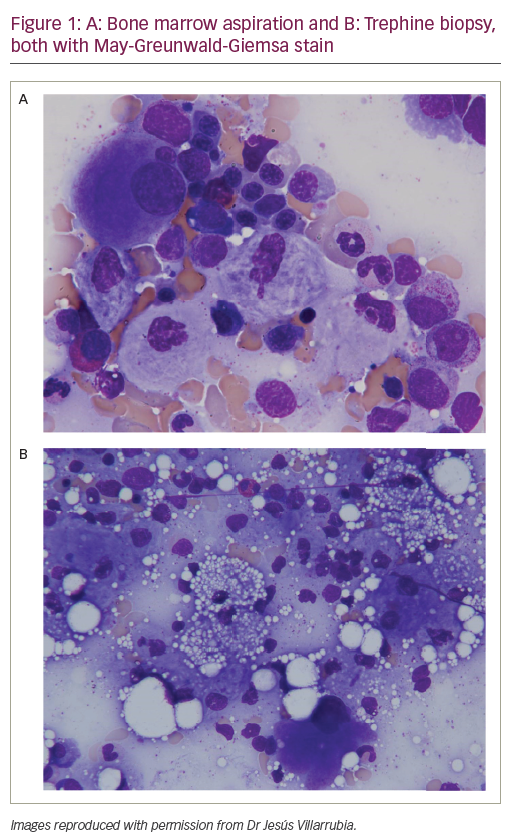

Commercially available systems were later developed and used in studies to investigate their ability to detect bleeding and thrombotic disorders, as well as their sensitivity to monitor the effects of therapeutic anticoagulants. The use of 96-well microtitre plates allows high throughput using small volumes of reagents and plasma that may or may not contain platelets. Slow-acting fluorogenic substrates are used to detect thrombin generation over time and the data are processed to generate a thrombogram. A typical thrombogram is presented in Figure 1 showing the major parameters of lag time, endogenous thrombin potential (ETP), peak height and time to peak.1

Although by themselves these parameters of thrombin generation have been reported to individually reflect changes in haemostasis, i.e. hyper- and hypocoagulability, it is not known whether they may provide more valuable risk assessment in combination.10 Recently, it has been suggested that a score system that considers normal/ abnormal values for each of the thrombin-generation parameters be applied to the clinical situation.10 These authors reported that using a score system may be more accurate for the identification of patients at risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared with using individual thrombin-generation parameters.

Although recent advances in technology and automation have allowed improved performance, reproducibility and data manipulation when using thrombin-generation assays, standardisation remains a concern, particularly with variability in the reagents, methods, sample preparation, substrates and calibrators that are used. Readers are referred to more comprehensive reviews related to technical considerations for thrombin-generation assays.11,12

Clinical Applications

The measurement of thrombin generation has been applied to detect a broad range of bleeding and thrombotic disorders and has been reviewed extensively elsewhere.1,11–13 Indeed, the ability of thrombin-generation assays to monitor and/or evaluate the combined haemostatic capacity of coagulation and fibrinolytic proteins, as well as platelets, potentially has the advantage over traditional laboratory tests to more closely represent in vivo haemostasis. Table 1 provides a summary of the types of bleeding and thrombotic disorder that can be detected by thrombin-generation assays.

Another potential application of thrombin-generation assays is to monitor anticoagulant therapy. For many years, PT and aPTT have been used to monitor warfarin and unfractionated heparin therapy, although both are limited by the absence of platelets in the test sample and, as stated earlier, do not account for approximately 95% of the thrombin generated at the end-point of the clotting reaction. Thrombin-generation assays that use PRP may provide more sensitive monitoring of therapeutic anticoagulants. Indeed, this may be an advantage in circumstances where more than one anticoagulant is used and for monitoring of antiplatelet agents. Moreover, thrombin-generation assays could potentially be used to monitor an array of direct thrombin inhibitors and anti-FXa anticoagulants, particularly as these new anticoagulants cannot be monitored using routine coagulation screening tests (see Table 1).

Finally, thrombin-generation assays may have the ability to predict patients at risk of thrombosis and/or recurrent thrombotic episodes.14–16 These studies reflect the growing evidence that monitoring thrombin generation in patients, and specifically ETP levels, could assist in the identification of patients at greater risk of developing recurrent VTE, although further large, well-designed prospective trials are required.

Conclusion

The future may see further development and/or evolution of currently available thrombin-generation assays. Examples may include a whole blood assay using a fluorogenic substrate that has recently been reported to be more sensitive for determining increases in thrombin generation in patients with previous VTE compared with PPP and PRP.17 Furthermore, detection of thrombin generation by an electrochemistry biosensor system shows promise for application to the point of care scenario.18

Future clinical studies should consider standardisation and normalisation of thrombin-generation methods as these appear to improve the variability of results.19 Time will tell how close we are to the useful application of thrombin-generation assays to the clinical situation. ■