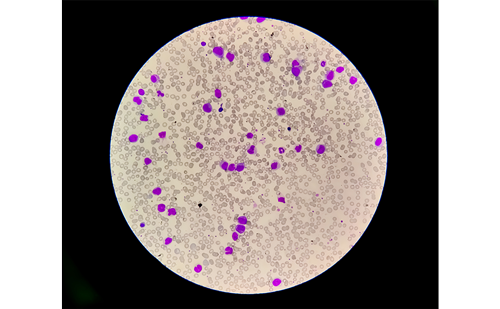

Anemia is defined by the World Health Organization as a hemoglobin (Hb) level <13 g/dl for men and <12 g/dl for women,1 and can be further subcategorized into mild (>10 g/dl), moderate (8–10 g/dl), severe (6.5–8 g/dl), and life-threatening (<6.5 g/dl) ranges. Anemia is a common comorbidity in cancer patients. It is multifactorial, with causes including nutritional deficiencies of iron, folate, or vitamin B12; renal disease; bone marrow involvement; blood loss; effects of cancer therapies; inflammation or activation of the immune system; and autoimmune hemolysis. Signs and symptoms of anemia include weakness, fatigue, pallor, tachycardia, dizziness, shortness of breath, and cognitive impairment. Anemia is highly prevalent in cancer patients; in fact, the analysis of data from over 15,000 patients enrolled in the European cancer anemia survey (ECAS) showed that 39 % were anemic at the time of enrolment in the survey2,3 and, in patients undergoing certain anticancer therapies or with particular types of cancer, this number can be as high as 90 %.4 Other factors that affect the frequency of anemia in cancer include advanced age and comorbidities such as renal dysfunction.5 It has been estimated that, of the approximately 10 million individuals in the US who have cancer, about 1.3 million who are not anemic at the time of diagnosis will develop anemia at some point during the course of their disease.6

In the previously mentioned ECAS study, cancer-related anemia was most frequently reported in patients with gynecological cancer (81.4 %), lung cancer (77 %), and lymphoma/myeloma (72.9 %).2 In addition, this study indicated that the longer patients received chemotherapy, the higher their risk of becoming anemic. Anemia is also a recognized complication of myelosuppressive chemotherapy in cancer patients.

Platinum-based chemotherapy regimens—such as those commonly used in lung, ovarian, and head and neck cancers—have combined kidney and bone marrow toxicity, and are well known as inducers of anemia.7 The myelosuppressive effects of chemotherapeutic regimens accumulate during therapy, meaning that the rate of anemia in cancer patients increases with additional treatment cycles.8 This cumulative effect has been documented in the ECAS survey, where the prevalence of anemia was shown to increase from 19.5 % in the first cycle of chemotherapy to 46.7 % after the fifth cycle.2 Significant predictive factors for the risk of developing anemia following chemotherapy include having a lower initial Hb level prior to treatment; having lung or gynecologic cancer versus gastrointestinal (GI)/colorectal cancer; having cancer at any other site versus GI/colorectal cancer; and treatment with platinum-based chemotherapies.9

To view the full article in PDF or eBook formats, please click on the icons above.