Anaemia in Older Persons

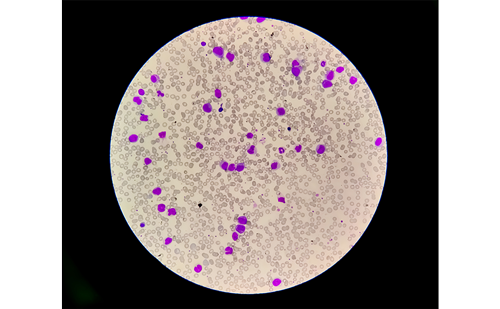

Anaemia is very common in older individuals. The reported prevalence ranges from <3% in healthy persons aged 65 years and over to 61% in older patients newly admitted to geriatric wards.1,2 These numbers differ not only because of varying definitions of anaemia, but also because of large differences in study populations with respect to gender, age, race, living situation and health status.1,2 In the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), a nationally representative study of non-institutionalised civilian adults in the US, the overall prevalence of anaemia among adults aged 65 years and over was 11% in men and 10.2% in women.3 In this study, anaemia was defined according to World Health Organization criteria (haemoglobin concentration less than 12g/dl in women and less than 13g/dl in men).4 Interestingly, the prevalence of anaemia increased significantly with age, up to 26.1% in men and 20.1% in women aged 85 years and over.3

In older persons, anaemia is associated with impaired survival,5–10 decreased physical performance, disability in daily living, cognitive impairment, depression, diminished quality of life and an increased number of hospital admissions.1,11–21 Considering the steep increase in the prevalence of anaemia in older individuals, and the exponential rise in the number of older individuals in our ageing society, anaemia in older individuals may have a significant effect on healthcare needs and costs in the decades to come.22 Adequate diagnosis and treatment of anaemia in older persons is therefore of vital importance.

Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Pernicious Anaemia – An Undeniable Cause of Anaemia

In 1849, Thomas Addison described patients with a ‘very remarkable form of general anaemia’. This severe type of anaemia, for which no treatment was available, was later called anaemia perniciosa (fatal anaemia) by Anton Biermer.23,24 Apart from severe haematological abnormalities, patients with pernicious anaemia also had a sore tongue, neuropathy of the hands and extremities and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.24 After many years of research, it appeared that patients with pernicious anaemia produce antibodies against ‘intrinsic factor’, a molecule in the stomach that is needed to bind and transport vitamin B12 through the gastrointestinal tract.23,24 Therefore, pernicious anaemia is a form of anaemia that is undeniably associated with severe vitamin B12 deficiency. Finding the cure for pernicious anaemia even led to the discovery of vitamin B12.23–29 Undoubtedly, patients with very low vitamin B12 concentrations (in case of pernicious anaemia) have to be treated: several studies showed large increases in haemoglobin after vitamin B12 administration in patients with pernicious anaemia or food vitamin B12 malabsorption.30–34 Subnormal Vitamin B12 Concentration – Also a Cause of Anaemia?

Due to the clear aetiology of pernicious anaemia, the outcomes of studies in patients with pernicious anaemia are often extrapolated to patients with subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations in the general population. As a result, subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations are considered to be associated with (mild) anaemia in general, but also with other conditions such as dementia, neuropathy and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.35–38 Therefore, physicians routinely measure vitamin B12 in patients with anaemia, and individuals with low serum concentrations of vitamin B12 (and normal folate concentrations) are frequently given intramuscular vitamin B12 supplements, often for many years.37–39 Also, since low serum vitamin B12 concentrations are very common in older individuals,40 screening older people for vitamin B12 deficiency has often been recommended.41,42

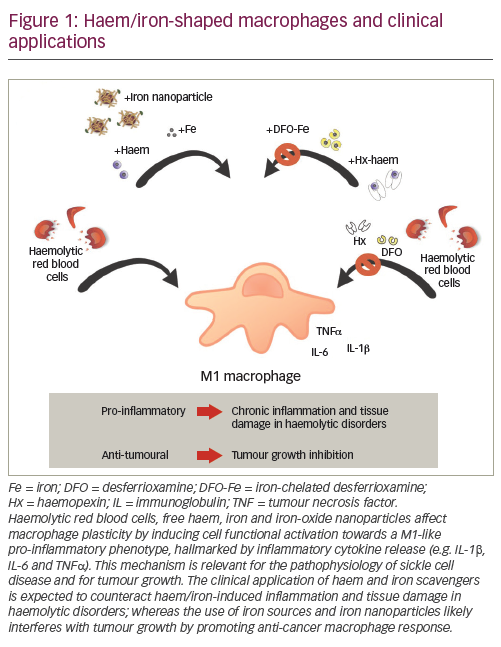

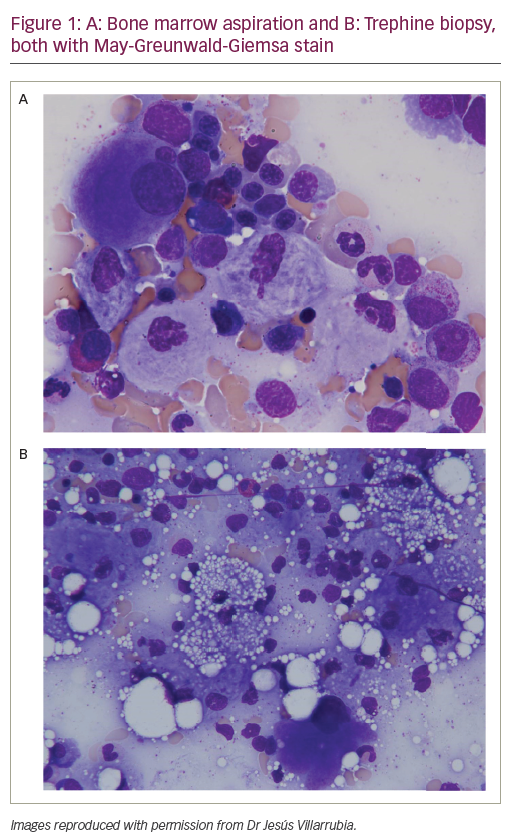

Although the biological role of vitamin B12 in haematopoiesis is well-defined,38,43–45 current evidence suggests that the outcomes of studies in patients with severe vitamin B12 deficiency should not be extrapolated to patients with subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations in the general population. In the Leiden 85-plus Study, a populationbased prospective follow-up study of 85-year-old individuals in Leiden, The Netherlands, we showed that low vitamin B12 concentrations (<150pmol/l) in 85-year-old subjects are not associated with the presence of anaemia at 85 years of age. The prevalence of anaemia in those with low vitamin B12 concentrations was 29%, and 25% in those with normal vitamin B12 concentrations (p=0.48). There were no differences in haemoglobin concentrations between subjects with low vitamin B12 concentrations and those with normal vitamin B12 concentrations (p=0.59). Also, participants with low vitamin B12 concentrations did not have a higher risk of developing anaemia from age 85 onwards (see Figure 1). Adjustment for possible confounders did not change our results.46

Interestingly, our study did not appear the first to cast doubt on the relationship between subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations and anaemia in older individuals. We performed a systematic review to evaluate the association between subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations and anaemia in older people in the published literature (reprinted with permission by BioMed Central).47 All published crosssectional and longitudinal observational studies in older individuals (mean or median age ≥60 years) on the association between vitamin B12 and anaemia were considered for inclusion in this review. In addition, we considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where subjects 60 years of age and over were treated with vitamin B12 (any dose and any form of administration) and were compared with subjects who were given a placebo. We used pre-defined clinical queries (both sensitive and specific) for aetiology and treatment as provided in PubMed (January 1949–October 2009) and EMBASE (January 1980–October 2009) using relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free text words for vitamin B12 and anaemia.

Twenty-one cross-sectional observational studies with a total number of 16,185 participants were included. The studies showed inconsistent results in terms of the association between subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations or vitamin B12 deficiency and anaemia in older subjects. In three out of 21 studies, an association between subnormal vitamin B12 and anaemia was found.48–50 For seven of 21 studies, the presence of an association was not clear because conflicting findings in terms of the presence of an association were reported.51–57 Eleven studies did not find an association between subnormal vitamin B12 and anaemia.58–68 Even in studies that had defined vitamin B12 deficiency using the lowest cut-off points for serum vitamin B12 levels,51,53,55 in which the strongest associations were to be expected, the presence of an association between vitamin B12 deficiency and anaemia was not clear, because conflicting findings regarding the presence of an association were reported. Similar inconsistencies were found with respect to the association between subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations and mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

Our own study appeared to be the only longitudinal study on the effect of low vitamin B12 concentrations (<150pmol/l) on developing anaemia.46 In our population-based sample of 85-year-old subjects, low vitamin B12 concentrations were not associated with an increased risk of having anaemia at baseline (prevalent anaemia) or developing anaemia during follow-up (incident anaemia). We found three randomised placebo-controlled trials with a total number of 210 participants that met the criteria for intervention studies for inclusion in our review.69–71 These three trials included patients with low or subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations at the start of the study. The first trial, by Hughes et al., included a random sample of 39 persons aged ≥65 years registered at general practices in a town in Wales, UK, who were treated for four weeks with intramuscular hydroxocobalamin or placebo. Haemoglobin was measured after five weeks.69 The second trial, by Hvas et al., included 140 persons in Aarhus, Denmark, with elevated methylmalonic acid concentrations (median age 75 years in the treatment group and 74 years in the placebo group), who received weekly intramuscular injections of cyanocobalamin or placebo for one month. Haemoglobin was measured after three months (13 weeks).70 In the third trial, by Seal et al., 31 persons in two geriatric hospitals in Melbourne, Australia, (mean age ≥78 years) received two doses of oral cyanocobalamin daily or placebo for four weeks.71 Owing to clinical heterogeneity (differences in methods of administration, dose of vitamin B12, outcome measures and treatment follow-up time), we did not combine the results in a metaanalysis. However, all three RCTs, which were regarded as high quality, showed no beneficial effects of vitamin B12 administration on haemoglobin concentrations, MCV, cognitive function and neurological symptoms.69–71 Neither was there any therapeutic effect in participants who were anaemic.70

Taking these findings into account, one may conclude that strong evidence of a positive association between subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations and anaemia in older persons in the general population is lacking.

Clinical Implications and Implications for Future Research

The findings mentioned above do not at all imply that patients with pernicious anaemia or malabsorption of vitamin B12 from food (with tissue depletion of vitamin B12 and very low vitamin B12 concentrations) should not receive vitamin B12 supplementation.31,32 However, apart from the undisputed case of pernicious anaemia, the clinical impact of subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations in older persons in the general population remains unclear. The fact that several observational studies and randomised controlled trials also showed no effect of vitamin B12 administration on cognitive function raises even more doubt about the consequences of subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations in older persons in the general population.72–74

Taking this into account, many older persons in primary care may receive vitamin B12 supplementation without evidence of clinical improvement. Although the cost of treatment with vitamin B12 in older individuals may be considered limited compared with other types of medical treatment, this does not justify initiation and continuation of treatment with vitamin B12 in older persons if not supported by medical evidence. These findings also raise doubt about the value of vitamin B12 measurements in diagnostic guidelines for anaemia as they may distract attention from other possible underlying causes. Additional proof of the (lack of) effectiveness of treatment with vitamin B12 in older patients with anaemia and subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations would be provided by a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial in which older patients with anaemia and subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations either receive usual care with vitamin B12 or placebo. However, before such a trial has been performed, the accumulating evidence suggests that clinicians should at least reconsider the risks of low vitamin B12 concentrations before starting cyanocobalamin or hydroxocobalamin supplementation in older individuals.75 The subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations may not be the cause of the anaemia, and supplementation with vitamin B12 may therefore not lead to a rise in haemoglobin concentrations.

Conclusion

Despite the undisputed case of pernicious anaemia, evidence of a positive association between subnormal serum vitamin B12 concentrations and anaemia in older persons is limited and inconclusive. If anything, given the high clinical relevance of anaemia in old age, we recommend more well-designed intervention studies of appropriate size and duration with timely follow-up periods to determine whether supplementation of older persons with subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations has a beneficial effect on haematological parameters. ■