Phenotypic diversity within the β-thalassaemia syndromes has traditionally received considerable interest, with several molecular and environmental modifiers of disease severity so far described.1 Patients with transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia major (TM) suffer the most severe form and show the highest mortality rates.1 Nevertheless, the introduction of safe transfusion practices and effective iron chelation therapy continues to improve patient survival, allowing for several clinical complications to have time to manifest.2 The term β-thalassaemia intermedia (TI) was first suggested to describe patients who have milder anaemia compared with patients with TM and who usually present to medical attention later in childhood and remain largely transfusion-independent. However, recent evidence suggests that the diagnosis of TI carries higher morbidity than previously recognised, especially in the transfusion-independent patient, where the mechanism of disease remains largely unbalanced.3

Three main factors highlight the pathophysiology of TI: ineffective erythropoiesis, chronic anaemia/haemolysis, and iron overload secondary to increased intestinal absorption.3 The extreme diversity in phenotypic expression within the diagnosis of TI itself led to a wide variation in observed clinical complications and management practices.3,4 Among the medical complications of TI that were found to occur at high rates, even more frequently than in patients with TM, are thromboembolic events (TEE).5 Here, we review current evidence on TEE in thalassaemia patients, with special emphasis on TI.

Pathophysiology

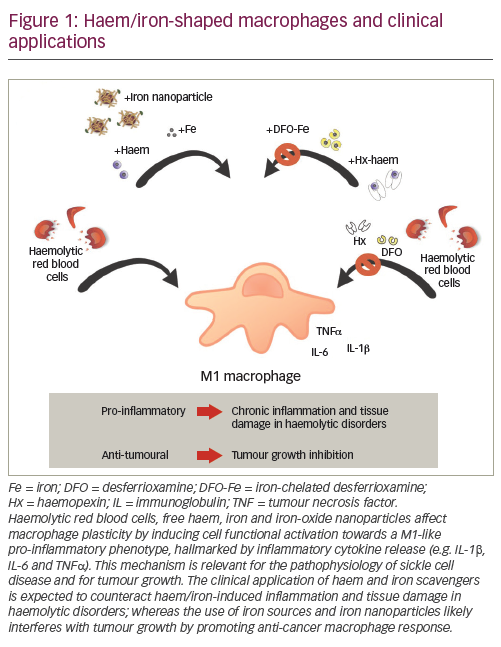

Hypercoagulability in patients with thalassaemia has been attributed to several factors (see Figure 1).5,6 It is often a combination of these factors that leads to TEE.

It is widely accepted that patients with thalassaemia have chronically activated platelets and enhanced platelet aggregation,7 as confirmed by the increased expression of CD62P (P-selectin) and CD63, markers of in vivo platelet activation.8,9 Splenectomised thalassaemia patients have high platelet counts,10,11 but with a shorter lifespan due to enhanced consumption.12 It has also been shown that splenectomised TM and non-splenectomised TI patients have four to 10 times higher levels of metabolites of prostacyclin (PGI2) and thromboxane A2, both markers of haemostatic activity, than controls. However, no significant difference was found between TM and TI patients.13 Furthermore, the oxidation of globin subunits in thalassaemia erythroid cells leads to the formation of haemichromes14 which precipitate, instigating haem disintegration and the eventual release of toxic non-transferrin-bound iron species.15 The free iron in turn catalyses the formation of reactive oxygen species, leading to oxidation of membrane proteins and formation of red-cell ‘senescence’ antigens such as phosphatidylserine,16 which cause the thalassaemic red blood cells (RBCs) to become rigid and deformed and to aggregate, resulting in premature cell removal.17 Thalassaemic RBCs with negatively charged phospholipids increase thrombin generation,18,19 as evidenced by studies using annexin V, a protein with high affinity and specificity for anionic phospholipids.19 Splenectomised patients have a substantially higher number of these negatively charged RBCs and in turn show higher thrombin generation.20,21 TI patients were also found to have higher levels of procoagulant microparticles of RBC, leukocytic and endothelial origins compared with controls;22 the contribution of these fragments to thromboembolic events in TI is under investigation.

The presence of other peripheral blood elements in thalassaemia patients, such as E-selectin (ELAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), von Willebrand factor (VWF) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), indicates that endothelial injury or activation may be an aspect of the disease, aiding in the recruitment of white blood cells and RBCs and promoting thrombosis.23,24 Studies have demonstrated that RBCs from TM and TI patients show increased adhesion to cultured endothelial cells (EC).25

Inherited thrombophilia does not play a role in the hypercoagulability of thalassaemia,26,27 but high levels of antiphospholipid antibodies and low protein C and S levels have been documented.6 The presence of cardiac, hepatic or endocrine dysfunction in patients with severe iron overload may also contribute to hypercoagulability in thalassaemia.6

Clinical Implications

Epidemiological data on TEE in thalassaemia are scarce. Borgna-Pignatti et al. surveyed nine Italian paediatric thalassaemia centres, observing that 4 % of the 683 patients with TM and 9.6 % of the 52 patients with TI had experienced a TEE.28 The same group showed six years later that 1.1 % of 720 patients with TM in seven Italian centres had thrombosis.2 Cappellini et al. followed up 83 patients with TI over 10 years, 82 of whom were splenectomised and found that 29 % (24/83) experienced a venous TEE.21 One study directly implicated TEE as the cause of death in 2.5 % of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia patients.29 After examining data from 8,860 patients in the Mediterranean area and Iran, Taher et al. observed that TEE occurred 4.38 times (95 % confidence interval [CI] 3.14–6.10, p<0.001) more frequently in TI than TM, with more venous events occurring in TI and more arterial events occurring in TM.30 It was found that 14 % of mortalities in the whole group were due to TEE. Age above 20 years, splenectomy, family history of TEE and previous TEE were identified as the main risk factors for thrombosis in TI. Furthermore, the study showed that 68 % of TI patients that had a TEE had an average haemoglobin level of <9 g/dl and only 33 % were receiving regular blood transfusions, whereas 94 % were splenectomised. Moreover, patients receiving aspirin therapy had a significantly lower rate of recurrent TEE.30

The evidence for brain involvement in thalassaemia dates back to 1972, when 20 % of 138 TM patients in Greece were found to have neurological deficits compatible with transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs).31 Further evidence of TIAs causing neurological symptoms, such as headaches, hemiparesis and seizures, was shown in 2.2 % of patients with TM in Italy.28 Although overt stroke occurs more frequently in TM than TI (28 versus 9 %, respectively),30 it has been shown that as many as 37.5 % of patients with TI have asymptomatic brain damage on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).31 A more recent study on Lebanese patients determined that splenectomised adults with TI show a rate of silent white matter lesions as high as 60 %.32 The occurrence and multiplicity of the lesions were associated with older age (mean age of 36.1 years for lesion-positive patients versus 26.1 years for lesion-negative patients) and transfusion naivety (83.3 % of lesion-positive patients have never had a transfusion versus 25 % of lesion-negative patients).32 Another study from Iran followed to confirm these findings.33

In order to obtain much-needed clinical data concerning the optimal management of patients with TI, the Overview on practices in thalassaemia intermedia management aiming for lowering complication rates across a region of endemicity (OPTIMAL CARE) study evaluated 584 patients with TI at six comprehensive care centres (Lebanon, Italy, Iran, Egypt, United Arab Emirates and Oman) for the associations between patient and disease characteristics, treatment received and the rate of clinical complications.4 Thrombosis was the fifth most common complication, affecting 14 % of the patient population. On multivariate analysis, splenectomy, age above 35 years and a serum ferritin level ≥1,000 μg/l were associated with a higher risk of thrombosis.4

Conversely, a positive history of transfusion and a haemoglobin level ≥9 g/dl were found to be protective against thrombosis (see Table 1).4A higher occurrence of TEE with advancing age was also observed.34 In an effort to further understand the effect of splenectomy on the risk of TEE, a substudy of OPTIMAL CARE examined the characteristics of splenectomised patients with TI who developed TEE, aiming to identify high-risk patients who deserve further consideration for preventive strategies.35 Splenectomised patients with documented TEE (Group I, n=73) were age- and sex-matched to splenectomised patients without TEE (Group II) and non-splenectomised patients without TEE (Group III). The study determined that splenectomised TI patients who experience TEE are characterised by high nucleated RBC (≥300 x 106/l) and platelet counts (≥500 x 109/l) and are more likely to have evidence of pulmonary hypertension (PHT) and be transfusion-naive. As such, it was suggested that splenectomised TI patients at risk of developing TEE may be identified early on by these laboratory markers, presence of PHT and transfusion status.35 The study further examined how long it took for a TEE to develop following splenectomy and found the median time to thrombosis to be eight years.35 This delay indicates that TEE in splenectomised patients with TI is not an acute complication, but a manifestation of a chronic underlying process, further emphasising the need for a long-term treatment modality for prevention.35

Potential Preventive Strategies

Reduction of the proportion of circulating RBCs with thrombogenic potential may be achieved by introducing blood transfusions and may account for the lower rate of TEE in transfused versus non-transfused patients in previous studies.4,30,32,35 As such, transfusion therapy may be worthwhile to prevent the occurrence of TEE and other complications3 in TI patients for whom current practice does not necessarily recommend transfusions. Rather than enforcing the regular transfusion regimens implemented in TM, blood transfusion, if initiated in patients with TI, should be individually tailored to meet patient needs. Although introduction of blood transfusions will increase the rate of iron accumulation, effective methods of iron chelation are now available and the benefits of transfusion therapy may greatly outweigh the cost and inconvenience of iron chelation therapy.36 This approach requires prospective evaluation. Since splenectomy is a major contributor to TEE in patients with thalassaemia,37 reassessment of the procedure and appropriate risk–benefit evaluation prior to any attempt at splenectomy are called for. This is also essential in line with recent evidence on the high rates of other clinical complications after splenectomy,4 alongside the well-known increased susceptibility to infection.38

The literature lacks proper evidence on the role of antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents in the management of thalassaemia.6 The lower recurrence rate of TEE in TI patients who took aspirin after their first TEE, when compared with those who did not, suggests a potential role for aspirin.30 Moreover, the association of higher platelet counts with TEE in patients with TI further suggests a role for aspirin in this patient population.35 Foetal haemoglobin-inducing agents, such as hydroxycarbamide decitabine and decitabine, were also shown to lower plasma markers of thrombin generation.5 Hydroxycarbamide may modulate hypercoagulability in several ways: it may reduce phospholipid expression on the surface of RBCs and platelets and decrease RBC adhesion to thrombospondin, a thrombin-sensitive protein.5 It may also decrease the count of leukocytes, particularly monocytes expressing transcription factor, in addition to being a nitric oxide donor.39 It is recommended that each patient be assessed individually and assigned a personalised thrombotic risk based on intrinsic and extrinsic factors. High nucleated RBC and platelet counts, evidence of PHT and transfusion naivety can be used as indicators of TEE for splenectomised patients with TI and could be practical in the clinical setting.35 Such a risk assessment model would be valuable in identifying high-risk patients and targeting them for further testing. Several diagnostic tests are being explored to help identify patients at risk, with promising preliminary results.40

The hypercoagulable state in thalassaemia is due to multiple elements, a combination of which is often the drive behind a clinical TEE. Splenectomy and transfusion naivety are increasingly highlighted as important risk factors for TEE, especially in patients with TI. An individualised approach is recommended to establish an optimal strategy for preventing the occurrence of this complication of thalassaemia.