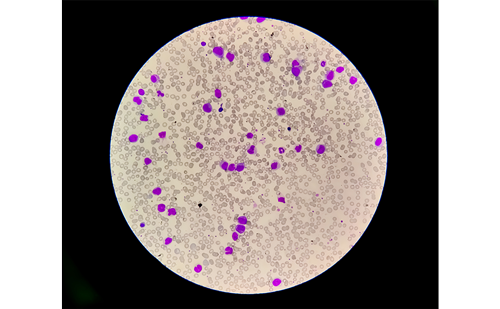

Beta-thalassaemia is a hereditary blood disorder arising from impaired synthesis of beta globin chains, and can result in a range of outcomes from asymptomatic carriers to severe anaemia.1 Symptomatic thalassaemia presents in around 1 in 100,000 people worldwide, and 1 in 10,000 in Europe.1 Transfusion-dependent beta-thalassaemia (TDT) is the most severe form of thalassaemia requiring lifelong management with regular red blood-cell transfusions. Iron overload following blood transfusions is a common challenge in management and contributes to elevated risk of cardiac disease, along with complications of the liver and endocrine systems.1,2 Iron chelation is an essential component of the management of TDT in paediatric and adult population.2,3 Data supporting the role of iron chelation in younger patients with TDT are scarce; however, several studies conducted recently are providing new evidence to help inform treatment selection.4,5

Q. What are the key challenges in administering lifelong red blood-cell transfusions in patients with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassaemia?

Patients with TDT must manage chronic, potentially fatal anaemia, and require a treatment strategy of lifelong red blood-cell transfusions to provide functioning blood cells. However, each transfusion is associated with the introduction of high levels of iron, which can quickly lead to severe iron overload.

Q. How have recent therapeutic advances affected outcomes in transfusion-dependent beta-thalassaemia?

Recent advances in treatment options have contributed to greatly improved morbidity and mortality outcomes in patients with TDT, who are now expected to live a relatively normal life, with manageable disease burden.

Q. What were the aims and outcomes of your recent study, DEEP-2, in patients with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassaemia?

DEEP-2 explored the efficacy and safety of iron chelation in paediatric patients with TDT.5 This is important because there has been a relative lack of meaningful treatment data in the paediatric population with haemoglobinopathies. The DEEP-2 study compared the effects of the two available oral iron chelating agents, deferiprone and deferasirox, over 12 months of treatment. Data from this trial should benefit treatment selection and improve outcomes in the paediatric population of patient with transfusion dependent haemoglobinopathies (TDH), namely TDT, sickle cell disease and haemoglobinopathy.

Q. What were the main efficacy findings of DEEP-2, and what factors should be considered when using iron chelators in the management of transfusion-dependent beta-thalassaemia?

Findings from the DEEP-2 trial support the use of iron chelation in the paediatric population with TDH. More precisely, both deferiprone and deferasirox can be used in setting, as there were no significant differences in efficacy or safety profiles, at least at the per protocol analysis. In order to further improve outcomes, physicians need to encourage compliance to treatment. Furthermore, rapid and accurate dosing adjustments are important in this population of patients.

Q. What can be done to further improve outcomes in this patient population?

It is important to determine how early intervention with iron chelation can be considered. Emerging data, such as the findings of DEEP-2, are providing support for initiation of iron chelation at a very early age. Once treatment commences, dose adjustment will play a key role in optimising outcomes in this paediatric population.