Epigenetic dysregulation in myelodysplastic syndromes – how important is it?

Our understanding of the biology and pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) has evolved dramatically in the last two decades. Evidence of an epigenetic background of the disease identified by a hypermethylation of specific genes and promoter-associated CpG islands was reported in the late 1990s1and first decade of this century.2 Multiple sequencing efforts have shed light in the molecular annotation of the disease3–6 and have allowed to better group and dissect the different entities within this heterogeneous group of diseases.7,8 Dysregulation of epigenetic processes such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, miRNA and splicing machinery are essential in MDS pathogenesis and, in fact, multiple mutations and epimutations in well characterised epigenetically related genes such as DNTM3A, TET2, ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1/2 and splicing factors such as U2AF1, SF3B1, ZRSR2 and SRSF2 have been consistently described.9–12 Functional assays in cellular and murine models exploring the leukemogenic potential of such mutations have also confirmed these findings13–18 As a result of this, despite the complexity and heterogeneity of MDS pathogenesis, MDS can be considered, at least partially, an epigenetic disease.

Interestingly, recent studies by several groups including Jaiwal et al.,19 Xie et al.20 and Genovese et al.21 have confirmed that many of such mutations, particularly DNTM3A, TET2 and ASXL1 mutations, can be identified with increased frequency in elderly individuals with no evidence of haematological malignancy as part of what has been named clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP). This is particularly relevant considering haematopoietic stem-cell aging is likely one of the mechanisms implicated in MDS clonal initiation and progression19,22–24 and that these same mutations are known to participate in this aging process. In fact, there is evidence supporting that individuals with CHIP, as those with idiopathic cytopenias of unknown significance (ICUS), characterised by cytopenias with no significant dysplasia and presence of CHIP-like mutations in up to 28% of cases, are at an increased risk of ultimately developing MDS.25,26These findings suggest epigenetic dysregulation is at the base of the progressive biological process driving clonal evolution leading to MDS.

Targeting the epigenome in myelodysplastic syndromes – state of the art and future perspectives

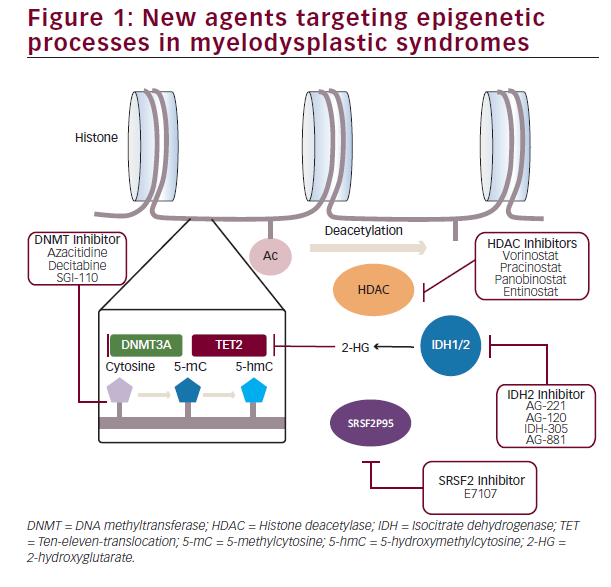

While the above mentioned findings have clearly advanced the knowledgebase of MDS pathophysiology, clear therapeutic and prognostic impact of this data still remains elusive and, despite a few exceptions, has not yet allowed modifying disease treatment. One of such exceptions was the development and subsequent approval by the FDA of azacitidine and decitabine, two cytidine analogues with a potent inhibitory effect of DNA methylation by induction of DNA methyl transferase (DNMT) depletion. Although approval of these agents led to a revolution of the treatment of these patients, reducing and delaying the risk of transformation to acute leukaemia and prolonging survival, only 40% of patients achieve responses to therapy and, in a majority of them, responses tend to be short-lived with eventual loss of response resulting in poor outcomes.27–29 To overcome this, multiple clinical trials evaluating the potential of combinations of new epigenetic modifiers with hypomethylating agents have been conducted. Post-translational modifications of histones by acetylation, methylation or ubiquination represent the most diverse mechanisms implicated in chromatin remodeling and regulation of gene expression30–32with aberrant expression and function of these regulators clearly participating in MDS pathogenesis. Modification of these abnormal histone modifications by histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors has been systematically tested in multiple clinical trials first as monotherapy, and subsequently in combination with azacitidine due to in vitro data suggesting potential synergistic effect of this combination.33 Ever since the initial study assessing the effectiveness of valproic acid in combination with azacitidine,34 multiple other HDAC inhibitors such as vorinostat,35 entinostat,36 panobinostat and, more recently, pracinostat have been explored in combination with azacitidine. However, despite these efforts in trying to improve the outcomes obtained with hypomethylating agents alone, histone Deacetylase inhibitor and hypomethylating agent (HDACi-HMA) combos have failed to significantly improve response rates of survival of patients with MDS. As a result of this, the interest has shifted to alternative strategies exploring not only epigenetic processes but also innate immunity signalling and immune checkpoint regulation amongst others.

Despite these underwhelming results, epigenetic deregulation in MDS is far more complex and heterogeneous than simple DNA hypermethylation or histone acetylation. Although less frequent than in acute leukaemia, approximately 4–12% patients with MDS have clones with detectable mutations in the isocitrate dehydrogenase genes IDH1 and IDH2. Presence of R132 in IDH1, and R140 and R172 mutations in IDH2 induce a disruption in the enzyme catalytic activity inducing a product shift from α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate which in turn causes inhibition of the ten-eleven-translocation (TET) genes and increased homeobox A (HOXA) activity responsible for a differentiation block. Development of specific inhibitors such as IDH-305 or AG- 120 in the case of IDH1mut, AG-221 in the case of IDH2mut or the dual inhibitor AG-881 have opened the possibility of specifically targeting this alterations. Initial results in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and MDS show response rates of 36–41% with 18% complete responses.37,38 This is specially promising in the context of patients with IDH mutations who lose response to hypomethylating

agents due to the absence of available standard therapies and otherwise poor prognosis.

Mutations in genes coding for splicing machinery factors represent the most frequent group of genomic abnormalities in MDS. Insight in the specific biological processes leading to particular disease phenotypes has rapidly evolved in the last 2 years. Mutations in SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1 and ZRSR2 rarely co-occur within a same clone and tend to appear in heterozygosis suggesting only limited degrees of abnormal splicing function are compatible with cellular viability. In fact, preliminary data presented in the last American Society of Hematology (ASH) meeting suggests inhibition of splicing machinery induces significantly increased reduction in leukaemia burden in spliceosomemutant leukaemias.39

In view of these advances, dissection of the specific epigenetic abnormalities present in different subsets of MDS will likely lead to a tailored selection of therapy guided by the particular genomic abnormalities present in each individual case (Figure 1).