Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, poorly differentiated and highly aggressive neuroendocrine cutaneous cancer with a high propensity to grow rapidly and metastasize early. Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is now estimated to be the causative factor in up to 80% of MCC cases.1Expand Reference Meanwhile, the remaining 20% are attributed to significant exposure to ultraviolet radiation.2Expand Reference The incidence of MCC in the USA is rising, with an estimated rate of 3,000 cases per year in 2025.3,434 This trend has been ascribed to improved diagnostic methods, an ageing population, increased overall sun exposure and the rising number of immunosuppressed patients.5Expand Reference

Patients typically present with enlarging red or pink nodules in sun-exposed areas. Approximately one-third of patients with MCC develop lymph node metastases, while another one-third of patients develop distant metastatic disease.6–8678 Given the rare nature of MCC, there is a lack of prospective clinical studies to guide treatment recommendations. Most patients present with locoregional diseases, and surgery is considered the first line of therapy typically followed by adjuvant radiation therapy (RT).9,10910 For poor surgical candidates or patients who refuse surgery, retrospective data have shown good outcomes with definitive RT.8,11811 Several studies have shown a wide range of locoregional recurrence rates after surgery alone.12–1512131415 MCC-specific 5-year survival rates range from approximately 25 to 75%, contingent upon the stage of presentation at diagnosis.6,7,13,16671316

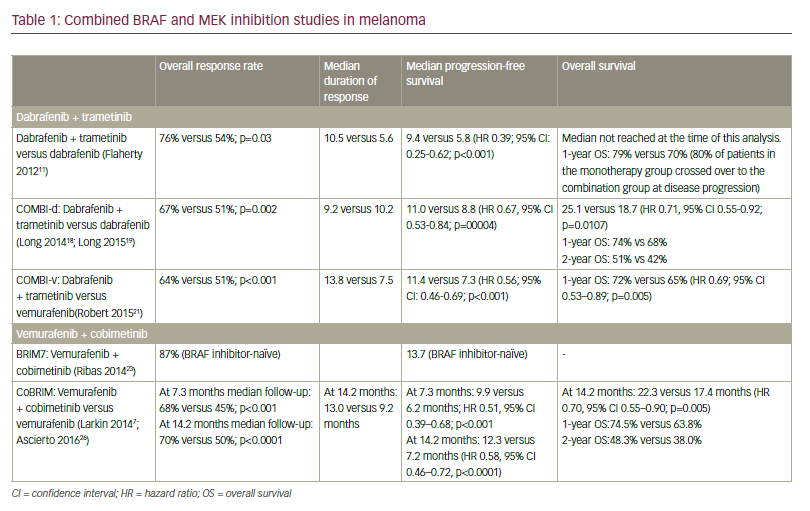

Many chemotherapy regimens have been studied in patients with MCC.17–19171819 Chemotherapy is associated with response rates ranging from 40 to 60% in the setting of metastatic disease, but responses tend to be short-lived with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 3 months.20Expand Reference Some studies have suggested a relationship between the response rate of chemotherapy and the number of prior chemotherapy agents, with higher response rates seen in chemotherapy-naive patients versus chemotherapy-refractory patients.17–19171819 Although there are no prospective data directly comparing chemotherapy with immunotherapy, immunotherapy has been shown to yield better response outcomes and potentially offer longer-lasting responses than cytotoxic chemotherapy and may even provide lifelong disease control in the setting of metastatic disease. Due to this, chemotherapy is now typically recommended only in certain circumstances, such as in immunotherapy-refractory diseases and/or if anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD1) or anti-programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) therapy is contraindicated. Immunological dysregulation has been a subject of interest in the context of MCC, especially because microscopic examinations of MCC tumours have revealed the presence of lymphocytic infiltration, emphasizing the immunogenic nature of this disease.21Expand Reference In addition, recent studies reported a positive correlation between tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis, suggesting that an immune-based response might lead to better treatment outcomes.22,232223 Several immunotherapeutic agents have been approved for patients with advanced MCC over the past years. Currently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 1.2023 guidelines recommend avelumab, nivolumab or pembrolizumab for disseminated MCC, while the recently approved agent retifanlimab is recommended for patients not amenable to surgery or RT.24Expand Reference The evolution of these breakthroughs has resulted in the initiation of multiple ongoing clinical trials, as shown in Table 1.25–30252627282930

Table 1: Ongoing Merkel cell carcinoma clinical trials25–30252627282930

|

Clinical trial name |

NCT identifier |

Phase |

MCC stage |

Intervention |

Primary endpoints |

Estimated enrolment |

Status |

|

Immunotherapy Adjuvant Trial in Patients With Stage I-III Merkel Cell Carcinoma (I-MAT)25Expand Reference |

NCT04291885 |

II |

I–III |

Avelumab and placebo |

RFS |

132 |

Recruiting |

|

Chemo-immunotherapy in Patients With Resectable Merkel Cell Carcinoma Prior to Surgery (MERCURY)26Expand Reference |

NCT05594290 |

II |

IIA–III |

Retifanlimab, cisplatin and etoposide |

pCR |

36 |

Recruiting |

|

Navtemadlin (KRT-232) With or Without Anti-PD-1/Anti-PD-L1 for the Treatment of Patients With Merkel Cell Carcinoma27Expand Reference |

NCT03787602 |

I and II |

IV |

Avelumab and KRT-232 |

ORR |

115 |

Recruiting |

|

Targeted Therapy and Avelumab in Merkel Cell Carcinoma (GoTHAM)28Expand Reference |

NCT04261855 |

I and II |

IV |

Avelumab, EBRT and Lutetium-177 dotatate |

PFS |

38 |

Recruiting |

|

Phase II Study of Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Combination With Immunotherapy for Patients With Merkel Cell Cancer (iPRRT)29Expand Reference |

NCT05583708 |

II |

IV |

Pembrolizumab and Lutetium-177 dotatate |

ORR |

18 |

Recruiting |

|

Testing the Addition of Radiation Therapy to Immunotherapy for Merkel Cell Carcinoma30Expand Reference |

NCT03304639 |

II |

IV |

Pembrolizumab and SBRT |

PFS |

9 |

Active but not recruiting |

EBRT = external beam radiation therapy; MCC = Merkel cell carcinoma; NCT = National Clinical Trial; ORR = objective response rate; pCR = pathologic complete response; PD-1 = programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1 = programmed death ligand-1; PFS = progression-free survival; RFS = recurrence-free survival; SBRT = stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Historically, the Response Evaluation Criteria for Solid Tumors criteria have been used to assess the treatment response in patients treated with chemotherapy. However, the utilization of these criteria to assess treatment responses in patients undergoing immunotherapy has proven to be problematic, given that a significant number of patients experience the initial disease ‘pseudo-progression’, characterized by a subsequent latent or delayed treatment response. This phenomenon might cause physicians to consider switching immunotherapy agents and/or consider salvage therapy options prematurely.

Within this article, we review the treatment landscape of MCC focusing on the most recent advances in immunotherapy. In addition, we discuss near-future potential implications for immunotherapy in the multimodality management of MCC. We searched PubMed in September 2023. Search was not restricted by dates, and criteria used include ‘Merkel cell carcinoma’, ‘immunotherapy’, ‘retifanlimab’, ‘pembrolizumab’, ‘nivolumab’, ‘ipilimumab’ and ‘avelumab’. Only interventional studies were included in our review article.

Anti-programmed death-1 and anti-programmed death ligand-1 agents in Merkel cell carcinoma

Avelumab

Avelumab, a PD-L1-blocking antibody, has shown safety and efficacy in the setting of metastatic MCC (mMCC). In 2017, the phase II JAVELIN Merkel 200 trial (Avelumab in Participants With Merkel Cell Carcinoma; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02155647) established avelumab monotherapy as a new therapeutic option for disseminated MCC.31–33313233 Part A of this prospective, multicentre phase II study initially enrolled 88 immunocompetent patients with stage IV MCC, which is chemotherapy-refractory MCC.32Expand Reference Of note, the inclusion criteria require neither PD-1/PD-L1 nor polyomavirus status of the patients. Avelumab infusion was given every 2 weeks at a dose of 10 mg/kg as a second-line or later treatment after the initial treatment with chemotherapy. At a median follow-up of 10.4 months, 31.8% of the patients had an objective response (complete or partial response), with 82% of responders still experiencing ongoing responses at the time of the analysis. Grade 3 toxicity rates were seen in 5% of the patients. Part B of this phase II trial, a pre-planned analysis, assessed the response rates of avelumab monotherapy in 39 treatment-naive patients with mMMC.33Expand Reference The objective response rate (ORR) was 62.1%, with a median follow-up of 5.1 months. Within the cohort of patients who had a response, 83% of them had a duration of response of at least 6 months. No treatment-related deaths or grade 4 toxicities were reported. After a median follow-up of 65.1 months, D’Angelo et al. reported the 5-year update of part A of the phase II trial, reporting a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 26% (95% confidence interval [CI] 17–36%) for the entire cohort.33Expand Reference In reference to PD-L1-positive versus PD-L1-negative status, the 5-year OS rates were 28% (95% CI 17–40%) and 19% (95% CI 5–40%), respectively.

Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab is another PD-1 receptor-targeting monoclonal antibody that has been shown to be safe and effective in mMMC. The multicentre Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network-09/KEYNOTE-017 phase II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02267603), initiated in 2016, established pembrolizumab as a first-line therapy for advanced MCC.34,353435 Fifty patients with advanced MCC naive to systemic therapy received pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg body weight) every 3 weeks. Twenty-six patients who had received at least one dose of pembrolizumab were included in the initial report. Pembrolizumab was found to be associated with an ORR of 56% (the study’s primary endpoint), with an ORR of 62% in virus-positive and 44% in virus-negative cancer. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) of any grade were observed in 77% of patients, and 15% of patients experienced grade 3 or 4 TRAEs. The two patients experiencing grade 4 TRAEs discontinued the treatment, and there were no reported treatment-related deaths. The report observed the efficacy of pembrolizumab in treating both virus-positive and virus-negative advanced MCC. An update to the initial report was published in 2019, with the aim of investigating the response durability and OS of pembrolizumab monotherapy for advanced MCC.36Expand Reference This report analysed all 50 patients participating in the trial, finding an ORR of 56%, a 24-month OS of 68.7%, a 24-month PFS of 48.7% and a median PFS of 16.8 months; median OS was not reached. Tumour viral status was not found to be correlated with ORR, PFS or OS; however, a trend towards improved PFS and OS was observed in PD-L1-positive tumours. Grade 3 or greater TRAEs were observed in 28% of patients, with discontinuation of treatment in 7 of 50 (14%) patients, including one patient with a treatment-related death. The most recent update reported the 3-year outcomes and assessed factors associated with survival after first-line anti-PD-1 therapy in advanced MCC.37Expand Reference Among the 29 responders, ORR was reported to be 58%, median PFS was 16.8% and 3-year OS was 89.4% for responders and 59.4% for all 50 patients; median response duration and median OS were not reached. The completion of the 2-year treatment and a low neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio were associated with a response and longer survival.

Nivolumab

Nivolumab monotherapy has been explored as a neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy in MCC. In the phase I/II CheckMate 358 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02488759), nivolumab was investigated as a neoadjuvant therapy for resectable MCC.38,393839 Patients were administered two doses of 240 mg on days 1 and 15 prior to surgery, with nearly half achieving a pathological complete response and 54.5% exhibited radiographic tumour reductions of more than 30%. Importantly, this response was independent of MCPyV, PD-L1 or Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) status. Moreover, early markers of response, including complete pathological response and significant tumour regression, demonstrated a strong correlation with improved recurrence-free survival. Notably, there were no relapses in patients who had a complete response; however, two patients did not undergo surgery due to nivolumab-related toxicity. In the adjuvant setting, the multicentre phase II ADMEC-O trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02196961) explored nivolumab in completely resected MCC.40,414041 Patients were either randomly assigned to receive 480 mg dose of nivolumab every 4 weeks for a year or observed. The results demonstrated that nivolumab had a superior disease-free survival rate at 12 (85 versus 77%) and 24 (84 versus 73%) months. However, nivolumab was associated with increased grade 3–4 adverse events (42 versus 11%), but there were no treatment-related deaths. These trials demonstrate the therapeutic potential of nivolumab in both neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings for MCC.

Ipilimumab and nivolumab

The combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab immunotherapy has been demonstrated to be effective in the management of advanced MCC. Despite substantial advancements in the field of immunotherapy treatment for MCC, a significant number of patients develop anti-PD-1- or anti-PD-L1-refractory MCC and require second-line or ‘salvage’ immunotherapy. LoPiccolo et al. detailed a case review analysis of 13 patients, finding that combination immunotherapy could potentially provide increased efficacy in patients with refractory MCC.42Expand Reference This report also suggests that the use of another immunotherapy with a mechanism of action within the same pathway as a previously failed immunotherapeutic agent could yield non-redundant, effective anti-tumour activity. A subsequent study in 2021 analyzed five patients with mMCC refractory to anti-PD-L1 avelumab who were treated with combined ipilimumab and nivolumab at three sites in Germany.43Expand Reference An ORR of 60% was observed, with three patients having completed four courses of treatment, and the other two having completed two courses of treatment. One patient showed complete remission, and another showed partial remission of the disease; both patients completed four courses of treatment. Combined immunotherapy treatment was tolerated well, with no immune-related adverse events except for one case of grade 1 fatigue. The study demonstrated promising evidence towards the efficacy of ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy in use as salvage therapy for anti-PD-1- or anti-PD-L1-refractory MCC. More recently, Kim et al. reported the outcomes of a cohort of 50 patients treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy with or without stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) who were either previously exposed or naive to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy.44Expand Reference Thirteen ICI-naive patients and 12 patients with previous ICI treatment were assigned to the 25-patient, non-SBRT treatment group A, and 11 ICI-naive patients and 14 patients with previous ICI treatment were assigned to the 25-patient, SBRT treatment group B. With a median follow-up of 14.6 months, 100% of ICI-naive patients were found to have an objective response, with nine of these patients demonstrating a complete response. Patients with previous ICI exposure had a 31% ORR, and four of these patients had a complete response. Notably, grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events were observed in 40% of patients in group A and 32% of patients in group B. One patient in group B did not receive SBRT due to RT-related toxicity concerns, and two patients in group B were excluded because of non-evaluable status due to irradiation of target lesions. Overall, the study did not find the addition of SBRT beneficial for treatment efficacy but demonstrated the efficacy of ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy in both first-line and second-line settings.

Retifanlimab-dlwr

Retifanlimab-dlwr, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, received accelerated approval for patients with metastatic or recurrent locally advanced MCC earlier this year. This approval was based on the POD1UM-201, single-arm, multicentre phase II study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03599713) assessing the efficacy and safety of retifanlimab in patients with chemotherapy-naive or chemotherapy-refractory (three or less prior chemotherapy regimens) advanced/mMCC.45,464546 Retifanlimab was administered intravenously at a dose of 500 mg over 60 min every 4 weeks (on day 1 of each 28-day cycle). The primary efficacy analysis relied on patients who are chemotherapy-naive and have been under tumour assessment for at least 6 months following their initial confirmed response. Eighty-seven patients were treated with retifanlimab, and the primary analysis was based on the first 65 patients assessed, per protocol. Tumours were positive for MCPyV in 71% of the patients. The ORR seen in this cohort was 46.2%, with 41.6% (n=30) having a complete response. The disease control rate was 53.8%. Among the entire cohort of treated patients (n=87), 75.9% (n=66) of them had a treatment-emergent adverse event, with grade >3 toxicities seen in 28.7% (n=25) of the patients. A minority of patients (4.6%, n=4) discontinued retifanlimab due to immune-related adverse events (peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy, pancreatitis, eosinophilic fasciitis and polyarthritis).

Conclusion

In the realm of the treatment of MCC, immunotherapy has emerged as a promising strategy, leveraging the body’s immune system to combat and eliminate cancer cells. Nonetheless, this approach is not devoid of limitations. Immunotherapy suffers from a widely variable and unpredictable duration of response. While it is true that some patients benefit from complete and durable responses to immunotherapy, others may benefit for a limited time or may not benefit at all. Currently, there are no biomarkers available to predict which patients are more likely to have a treatment response and to assess the duration of response. Because of pseudo-progression, imaging response is not always perfectly equivalent to histological response. The cost-effectiveness of immunotherapy varies based on the drug-clinical scenario and healthcare system, but generally, the cost is a barrier to worldwide access to care.47Expand Reference For instance, the cost of immunotherapy drugs for end-of-life care has been escalating over the past years.48Expand Reference

A future goal is to identify the ideal treatment paradigm and order of therapies in the setting of advanced MCC. Multiple questions regarding the ideal timing, duration and appropriate patient population for the use of these newly approved therapeutic agents remain active areas of research. Clinical trials assessing the safety and efficacy of the combination of immunotherapy with surgery and/or RT are warranted, as are clinical trials exploring combinations of immunotherapeutic agents.