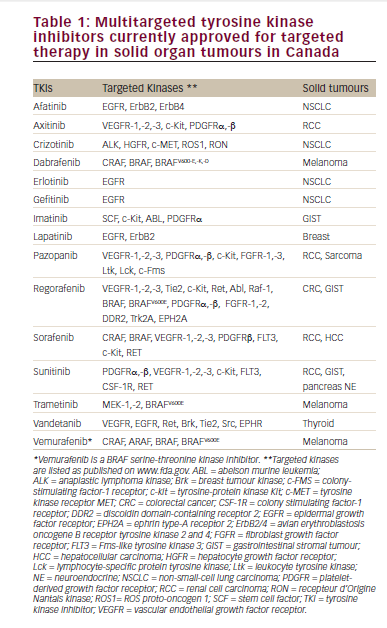

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are small anticancer molecules targeting protooncogenic tyrosine kinase signalling pathways.1 TKIs are now therapies used routinely in the treatment of many solid tumours such as gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), medullary thyroid cancer, breast cancer and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (Table 1). As opposed to cytotoxic chemotherapy, TKIs target specific mutated kinases that promote tumour angiogenesis and neoplastic cells growth, proliferation, and resistance to apoptosis. In some cases, such as the c-Kit mutation observed in GIST, tumour cells can be highly “addicted” to one or more oncogenic kinases2–4 and the inhibition of these kinases with a TKI can lead to a striking tumour response and trigger tumour lysis syndrome (TLS).5 It is noteworthy that in high-risk patients with haematological malignancies, targeted therapy including TKIs, monoclonal antibodies, chimeric antigen receptors and proteasome inhibitors are often associated with TLS.6

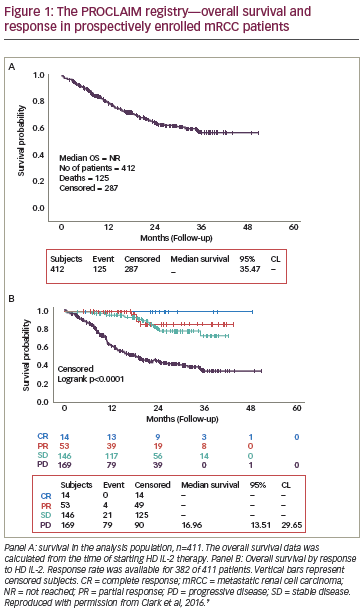

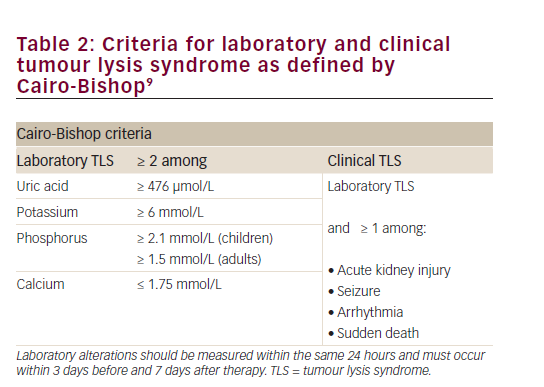

The pathophysiology of TLS is characterised by an extensive breakdown of tumour cells releasing intracellular contents into the bloodstream, leading to acidosis, hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperkalemia.7 These metabolic disturbances may in turn cause hypocalcaemia, acute kidney injury (AKI), cardiac arrhythmia, seizures, and death. Albeit considerably more common in haematological malignancies such as acute leukaemia and Burkitt’s lymphoma, it is now recognised that TLS may also occur in solid tumours.8 Most authors and oncologic societies define TLS according to the laboratory and clinical criteria proposed by Cairo & Bishop in 2004 (Table 2).9 As per this definition, TLS is typically diagnosed within a specific timeframe – i.e. 3 days before or 7 days after cytotoxic therapy initiation. However, TLS in solid tumours treated with TKIs has been repeatedly described during the second and third weeks following the initiation of therapy rather than within the first week.5 Against this background, we report a case of delayed TLS in a patient with advanced GIST treated with imatinib.

Case report

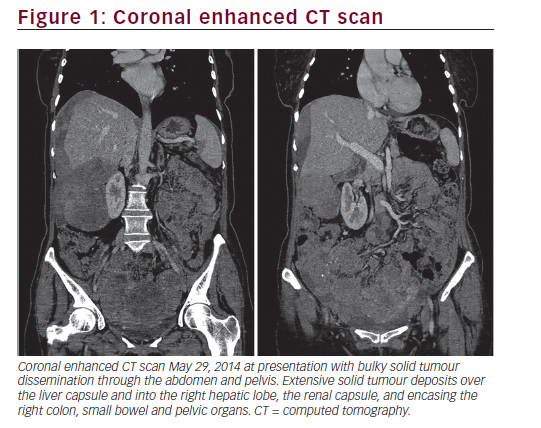

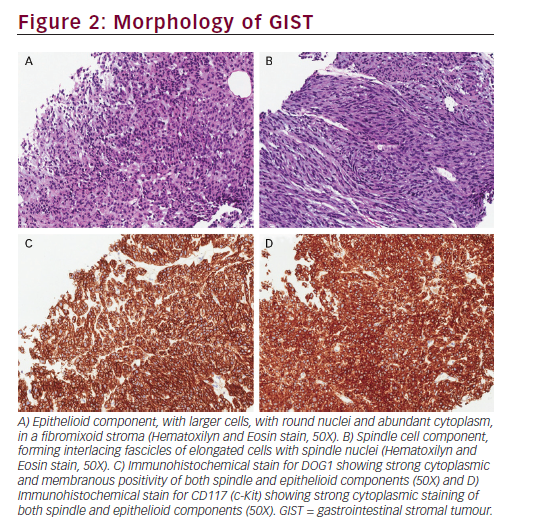

A 63-year-old female of Mediterranean origin presented with a three-month history of tiredness, anorexia, 20-kg weight loss and one-month history of vague abdominal discomfort. She was referred to our centre after a computed tomography (CT) scan had revealed extensive intra-abdominal neoplasm along with tumour deposit in the liver and along the hepatic and renal capsules (Figure 1). A core needle biopsy of the omentum demonstrated a neoplasm composed of mixed spindle and epithelioid cytology. The spindle component showed interlacing fascicles of blend tumour cells with spindle nuclei (Figure 2). The tumour had a low mitotic index of <5/50 high-powered fields (HPF).

Immunostaining revealed a strong expression of CD117 (c-Kit), DOG1 (“Diagnosed on GIST-1”) and CD34, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST, mixed cellularity subtype.

The patient was a life-long non-smoker and never consumed alcohol. She denied personal or familial history of cancer. Her past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with metformin and sitagliptin; hypertension treated with losartan, hydrochlorothiazide, and bisoprolol; and gastroesophageal reflux disease managed with omeprazole. On physical examination, the patient had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 and was somewhat cachectic. The abdomen was diffusely tender with right flank fullness.

As per current recommendations, the patient was initiated on imatinib mesylate, at a dose of 400 mg daily. During the second week of treatment, she developed progressive anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and loose stools. Fifteen days after initiation of imatinib, she presented to the emergency department with dyspnoea, hypotension, tachycardia and confusion. Laboratory tests (with pre-therapy baseline) revealed: Creatinine 527 (53)

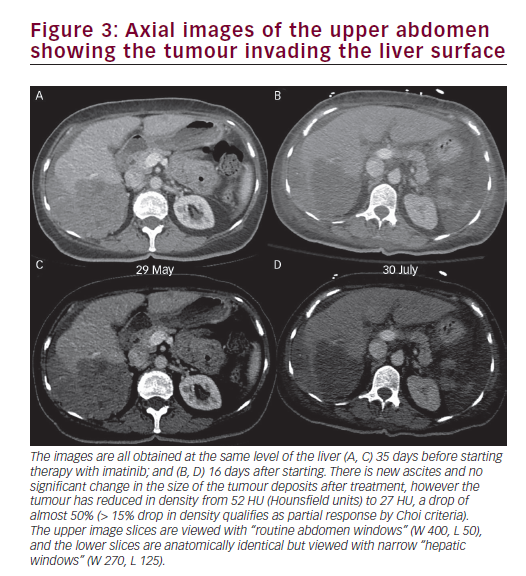

[22–75 μmol/L], pH <6.8 [7.33–7.46] with undetectable bicarbonate, lactate was 12.9 [0.4–2 mmol/L], potassium 5.8 [3.5–5.1mmol/L], phosphorus 3.04 (1.25) [0.81–1.58 mmol/L], corrected calcium 2.39 (2.57) [2.12–2.52 mmol/L], urate 1094 (547) [155–357 μmol/L], white blood count 17 [3.5–105 x 109/L], haemoglobin 111 [115–155 g/L], and platelets 598 [130–380 x 109/L]. The patient underwent aggressive fluid resuscitation and was transferred to the critical care unit on vasopressor support, with the intent to initiate sustained low-efficiency dialysis (S.L.E.D.). Four hours after initial bloodwork and prior initiation of S.L.E.D., corrected calcium had decreased to 2.21 mmol/L, phosphorus had decreased to 2.83 mmol/L, and potassium had increased to 6.3 mmol/L. Calcium phosphate product went from 90.2 to 77.4 mg2/dL2. A septic workup, including chest X-ray, blood and urine cultures was negative. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed the following day ruled out visceral perforation but did demonstrate clear evidence of tumour response with a decrease in tumour density by nearly 50%, meeting Choi criteria for partial response (Figure 3).10 Imatinib was held pending her improvement.

The patient was discharged from the intensive care unit after 4 days. Natural diuresis recovered progressively after one week of anuria and intermittent haemodialysis was weaned after 2 weeks. Imatinib 100 mg daily was reintroduced and progressively titrated to 400 mg over the subsequent month.

Discussion

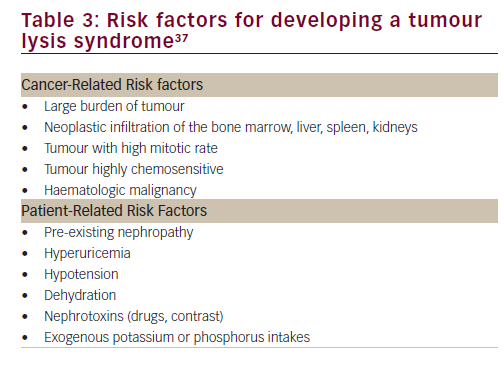

The present case illustrates well the typical laboratory and clinical manifestations of TLS. To our knowledge, there are only two other cases of TLS in GIST reported in the literature, one with sunitinib11 and another with imatinib.12 Although extremely rare in GIST, TLS can occur in presence of known risk factors (Table 3). In our case, the high tumour burden, the dehydration, the high baseline level of urate, and the patient exposure to various nephrotoxic compounds such as metformin, losartan and hydrochlorothiazide may all have predisposed out patient to develop a TLS. Once happening, the hyperuricemia and the high calcium-phosphate products lead to both urate crystals and calcium-phosphate precipitate in the renal tubules, causing potentially life-threatening AKI.13

Contrary to the diagnostic criteria of TLS proposed by Cairo & Bishop in 2004,9 the onset of the TLS occurred more than one week later than expected and 15 days after the initiation of imatinib. Of note, the diagnostic criteria were updated from the initial report of Hande and Garrow in 1993,14 who based their observation on a cohort of 102 patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hence, the conventional Cairo-Bishop definition antedates the introduction of most TKIs in oncology and did not include solid organ tumours.

Review of TLS reported in solid organ tumours

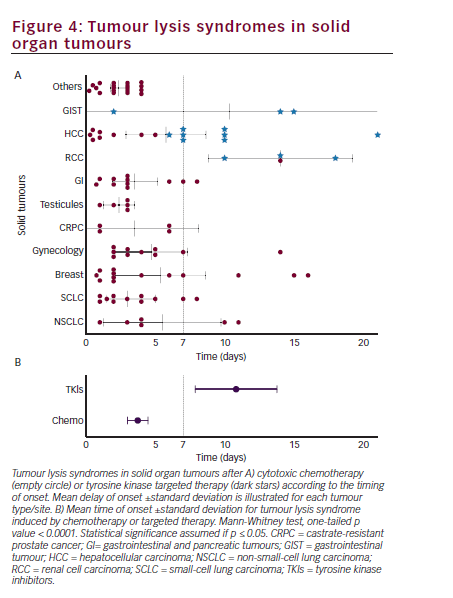

Mirrakhimov et al. published a review (PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Embase and Web of Science) of all reported cases of TLS in solid tumours between 1950 and February 2014.5 Using the same methodology, we conducted a comprehensive review the literature extending the timeframe to August 2014. We identified TLS in six cases of hepatobiliary tumours,15–20 two of gastrointestinal tumour,21,22 five cases of melanoma,23,24 and one case of non-small-cell lung carcinoma,25 RCC26 and metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary site.27 We pooled these cases with those identified by Mirrakhimov et al., and we excluded patients with spontaneous TLS (n=14) or TLS triggered by either radiation/radiofrequency (n=8), surgery/biopsy (n=1), coil embolisation (n=3), and those where the time of onset after treatment initiation was not provided (n=6).

Among the 101 cases reported, 14 were associated with the use of TKIs, namely sunitinib (three RCC and one GIST12), sorafenib (eight HCC15,19,20,28–32), and imatinib (two GIST12 in addition to the present case). From Figure 4A, it seems that TKIs may trigger TLS later than traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy does. Indeed, 12 out of 14 cases occurred between 7 and 21 days following the initiation of therapy, which is beyond the upper time limit defined by Cairo-Bishop. The average timing of occurrence of TLS was 10 days [7.8–13.7] following initiation of TKIs compared to 3 days [2.9–4.4] for cytotoxic chemotherapy (p<0.0001) (Figure 4B). To our knowledge, it is also the first time that timing of TLS is reported for non-haematological malignancies treated with conventional chemotherapy. We found that the risk for TLS is the highest during the first week of treatment, similar to what was described by Hande and Garrow14 in lymphomas.

The reasons why TKIs induce TLS at a later time point compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy is unknown. However, most cytotoxic chemotherapies damage rapidly dividing cells by disrupting cell cycle and inhibiting DNA and may provoke extensive simultaneous breakdown of cells in tumours harbouring several mitotic figures. On the other hand, TKIs increase tumour cell death by targeting mutated kinase receptors and their downstream signalling that allow tumours to grow or escape host immunity. Initiation of TKI might therefore not result in immediate cytolysis comparable to cytotoxic chemotherapy. One hypothesis may be that cellular death could be delayed depending on the level of tumour addiction to the mutated kinase and how critical the mutation is for the cell survival.4 The sensitivity of GIST to targeted therapy depends on the genetic alterations harboured in the KIT gene with an activating mutation of the exon 11 leading to a higher response rate to imatinib33 while GIST lacking driver genomic alterations in the protooncogenes c-Kit or platelet-derived growth factor receptor34,35 are essentially not responsive to imatinib.36

In summary, our review and case presentation highlight the lifethreatening nature of TLS, which can occur with targeted therapy with TKIs. It is crucial for clinicians to recognise that TLS associated with treatment with a multitargeted TKI may occur later than expected (i.e., outside the usual timeframe that is observed with cytotoxic chemotherapy) and caution should be exercised when initiating therapy particularly in patients who are at higher risk. For high-risk patients with predisposing factors, we suggest that it is reasonable to monitor patients’ electrolytes and renal function at least weekly during the first month of therapy. The currently accepted Cairo-Bishop definition should be revised to specify that in the cases where a TKI is commenced, laboratory and clinical TLS could be diagnosed up to 3 weeks following its introduction.